Whatever other impacts that our prolonged cost of living crisis are having on students, it’s not (yet) causing a significant drop-off in completion, continuation or even undergraduate enrolment.

There are signals and signs around the edges – not least the alarming reduction in home domiciled postgraduate study.

It’s also the case that while people think that the international PGT collapse is all about immigration, the relative strength of the pound when compared to the currencies of our major recruitment markets has made things much more expensive for non-EU international students than they used to be.

At least for home students, given the lazy way that policymakers tend to judge the impact of student finance policy is to just point at access figures and say “look, they’re still coming”, the situation doesn’t feel like an emergency:

This Government believes that we need to be fair not only to students but to taxpayers. It is worth noting that, in England, those from disadvantaged backgrounds are 74% more likely to go to university than they were in 2010. We have put together a substantial package to help students with the cost of living, including a £286 million welfare support fund, which we give to the Office for Students to ensure that students with difficulties are helped.

Robert Halfon Minister of State (Education), March 2024

For me, the better question has long been what sort of experience students are having – whether they’re happy, taking advantage of what’s on offer, and actually learning anything – rather than hanging on in there and hoping their life gets better after graduation.

To this end as part of our pulse polling partnership with GTI/Cibyl (which our subscriber SUs can take part in for free), we’ve been interrogating the impacts of the crisis from multiple angles. (Polling that follows is from two waves April and May, weighted for gender, age, and provider type, n= between 1200 and 1800 depending on the question and wave(s)).

I’ve deliberately not presented the whole country or whole student body here – as their experience bifurcates, it’s becoming increasingly meaningless to do so, and weighting samples for characteristics, along with UG and PGT and by home nation, can end up painting a national pictures that breed complacency. Instead I’ve focussed on a series of splits in the data. As ever, not all correlation is causation.

No surprises

In the polling we asked students whether they thought they were in financial difficulties in the same way that ONS was doing a while back:

- No, I’m comfortably well off

- No, I’m managing well enough

- No, I’m just about managing

- Yes, I’m in minor financial difficulties

- Yes, I’m in major financial difficulties

We also asked if a students’ financial position is better, the same or worse than last year.

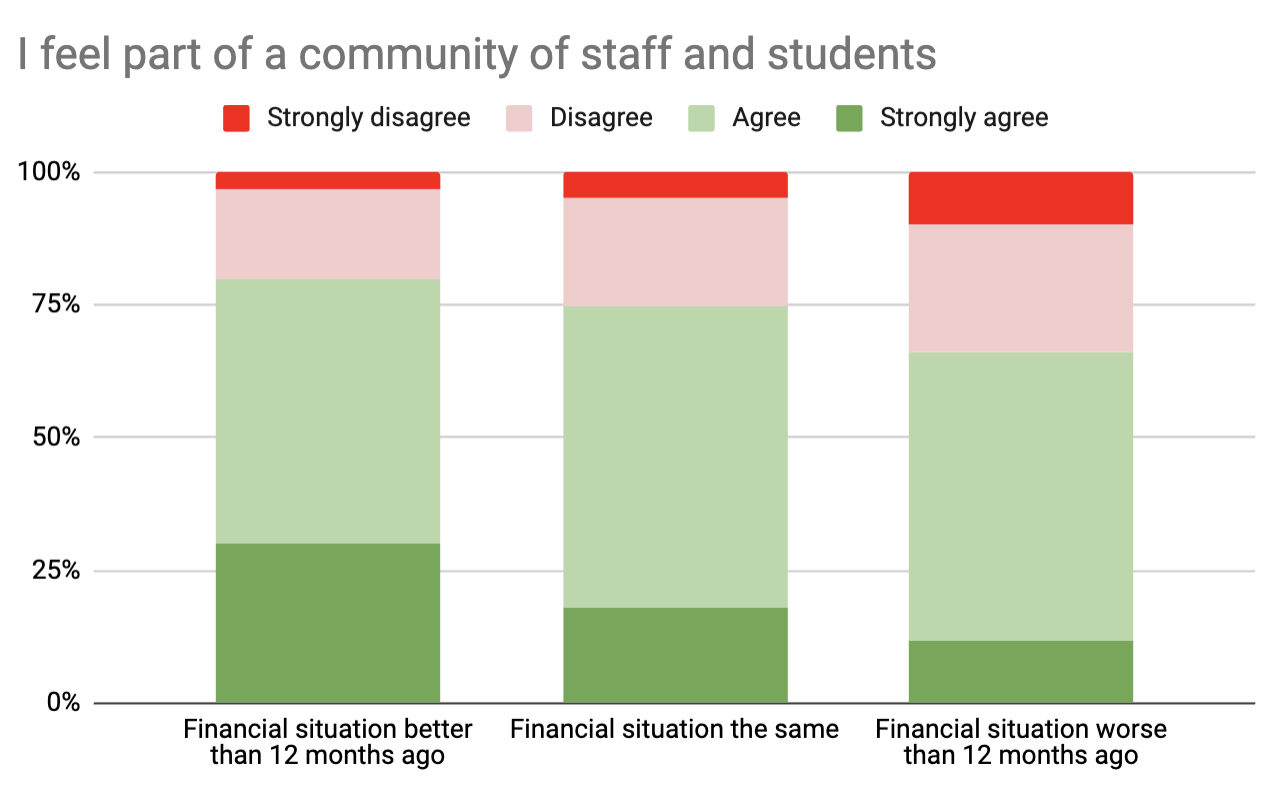

If we take the old NSS question on belonging (“I feel part of a community of staff and students”), the differences are quite stark:

And as the situation worsens, it seems to be having the impact we might expect it to have on students’ ability to maintain a community of contacts and friendships:

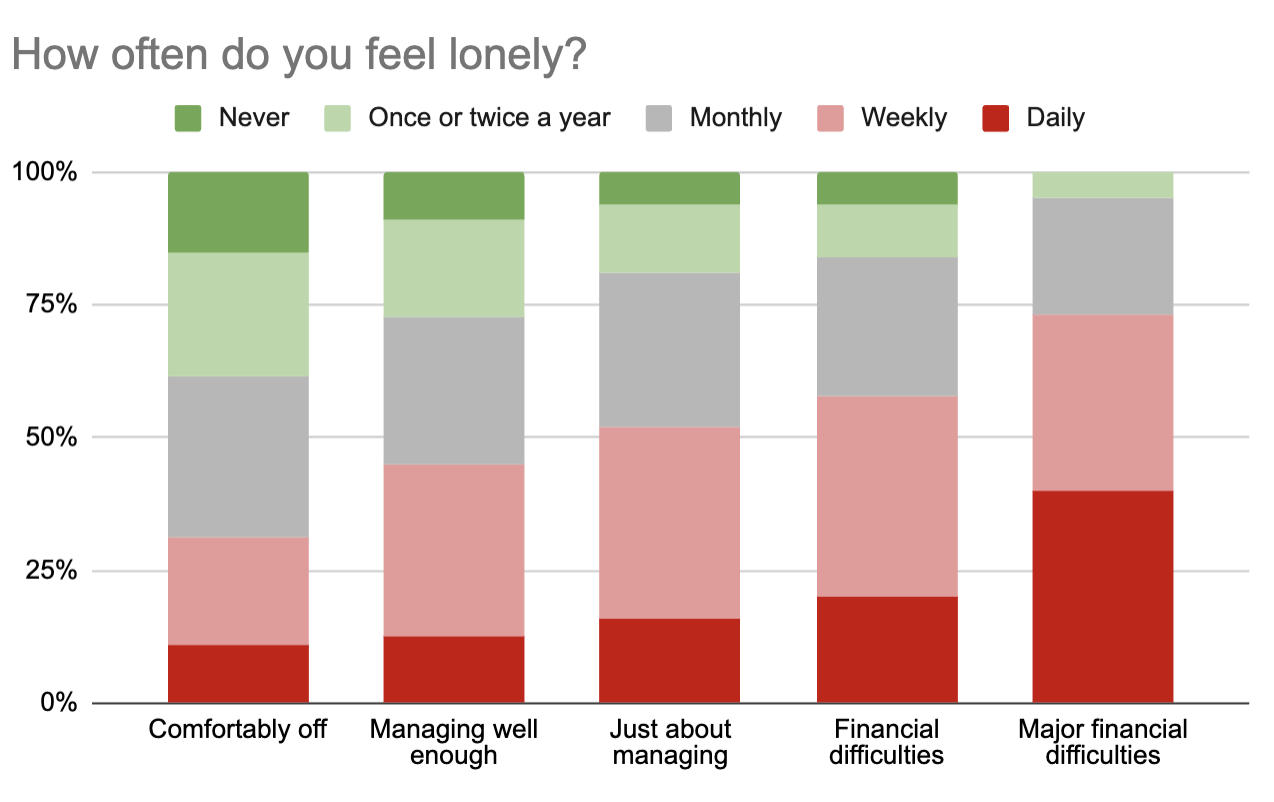

…with similar results when we look at loneliness:

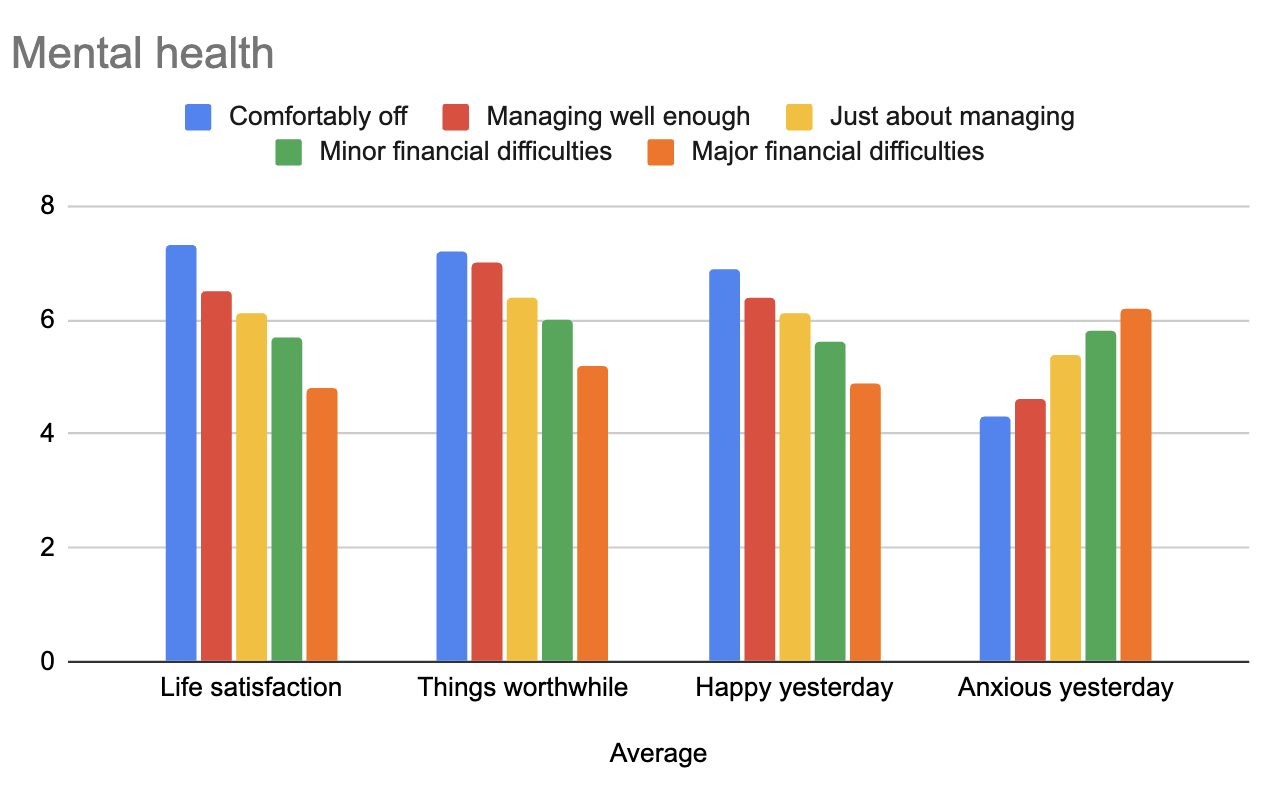

We can use the same categories to interrogate the relationship between financial position and mental health:

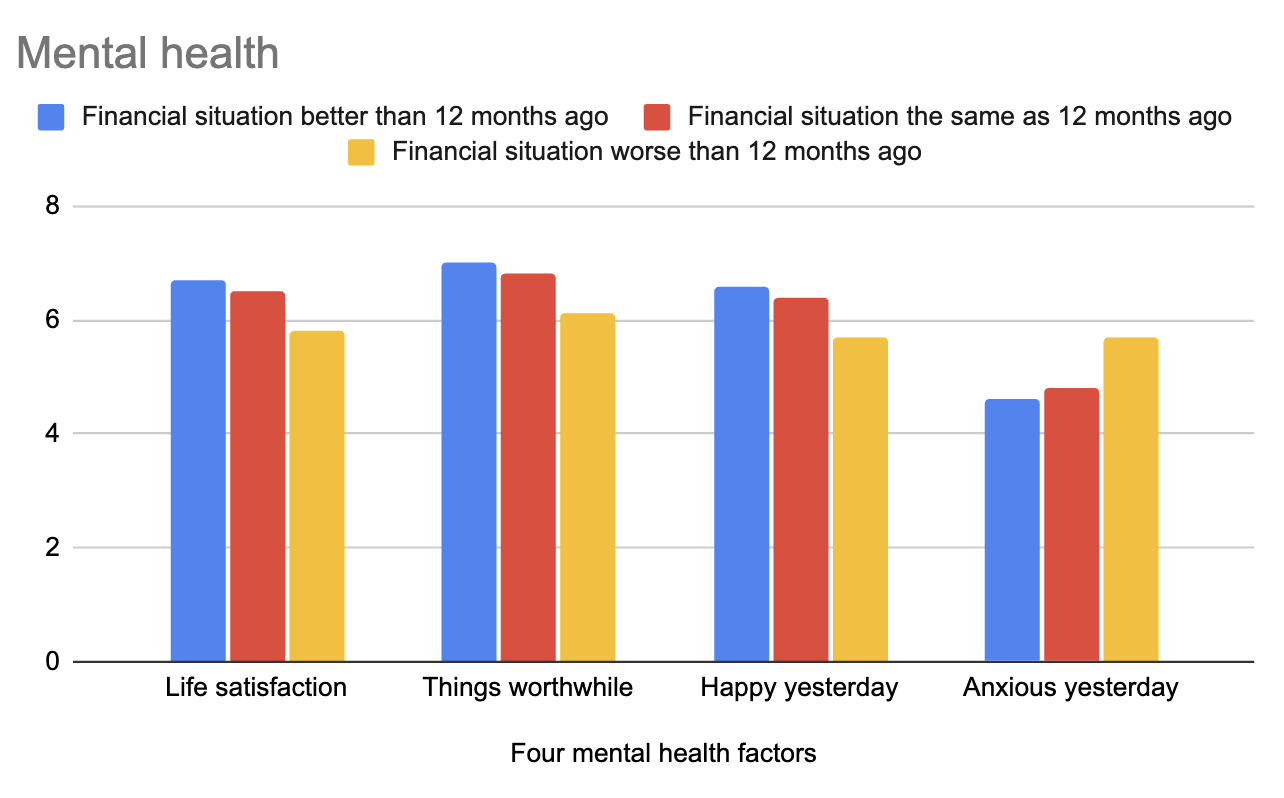

And there are similar results when students compare their financial situation to a year ago:

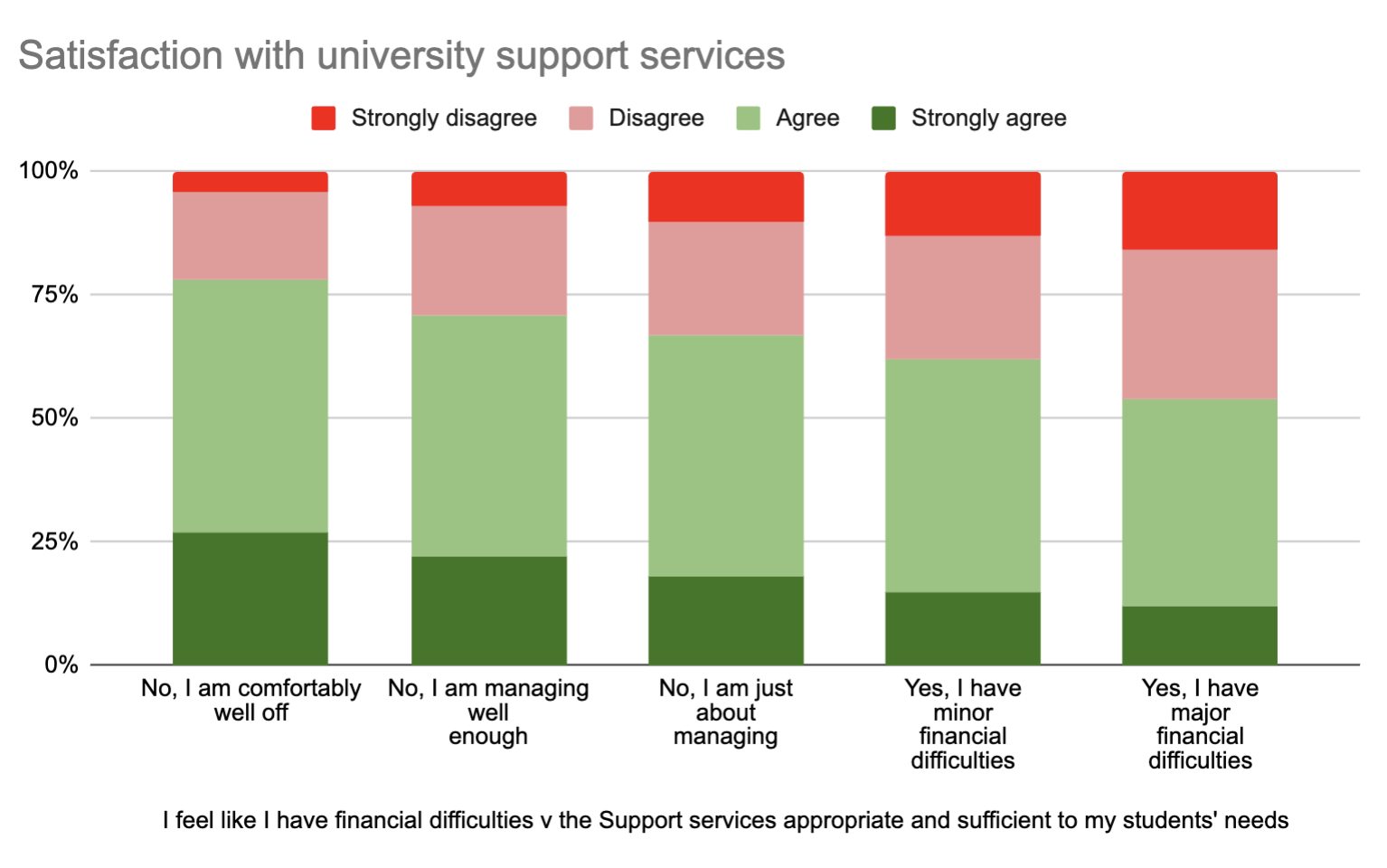

Financial position – perhaps inevitably – then also correlates with students’ satisfaction with university support services:

That the baffling decisions were made back in 2020 to remove the NSS question on community, and include an NSS question on awareness of wellbeing services but not on their effectiveness or appropriateness, is looking more and more like a mistake.

Wider impacts

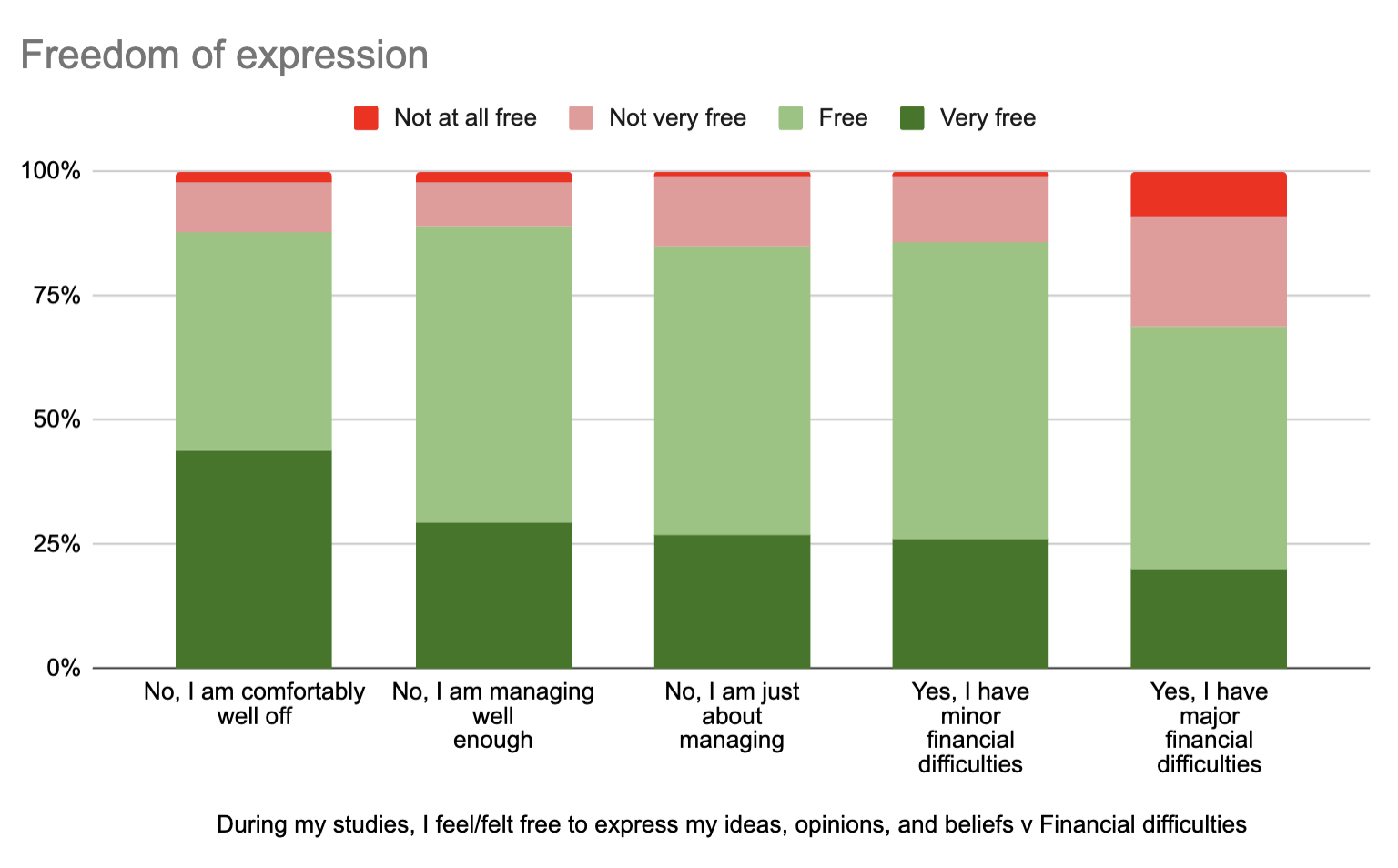

But these are not the only ways in which students’ financial situation can impact their experience. If we take the NSS question on freedom of speech, those who assume that the silent are all “anti-woke” be surprised by these numbers:

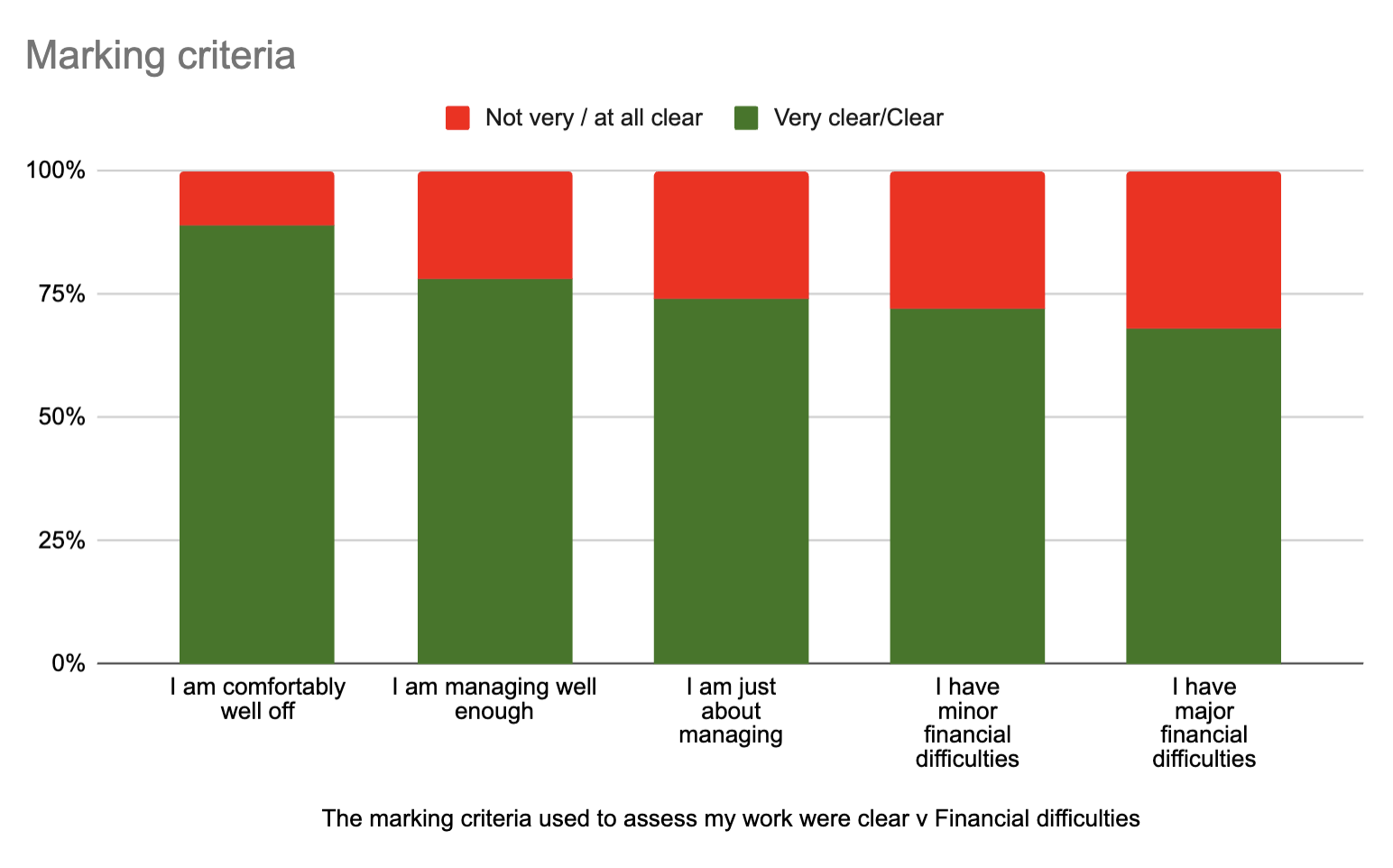

There are also significant differences on other NSS questions – like whether marking criteria were clear:

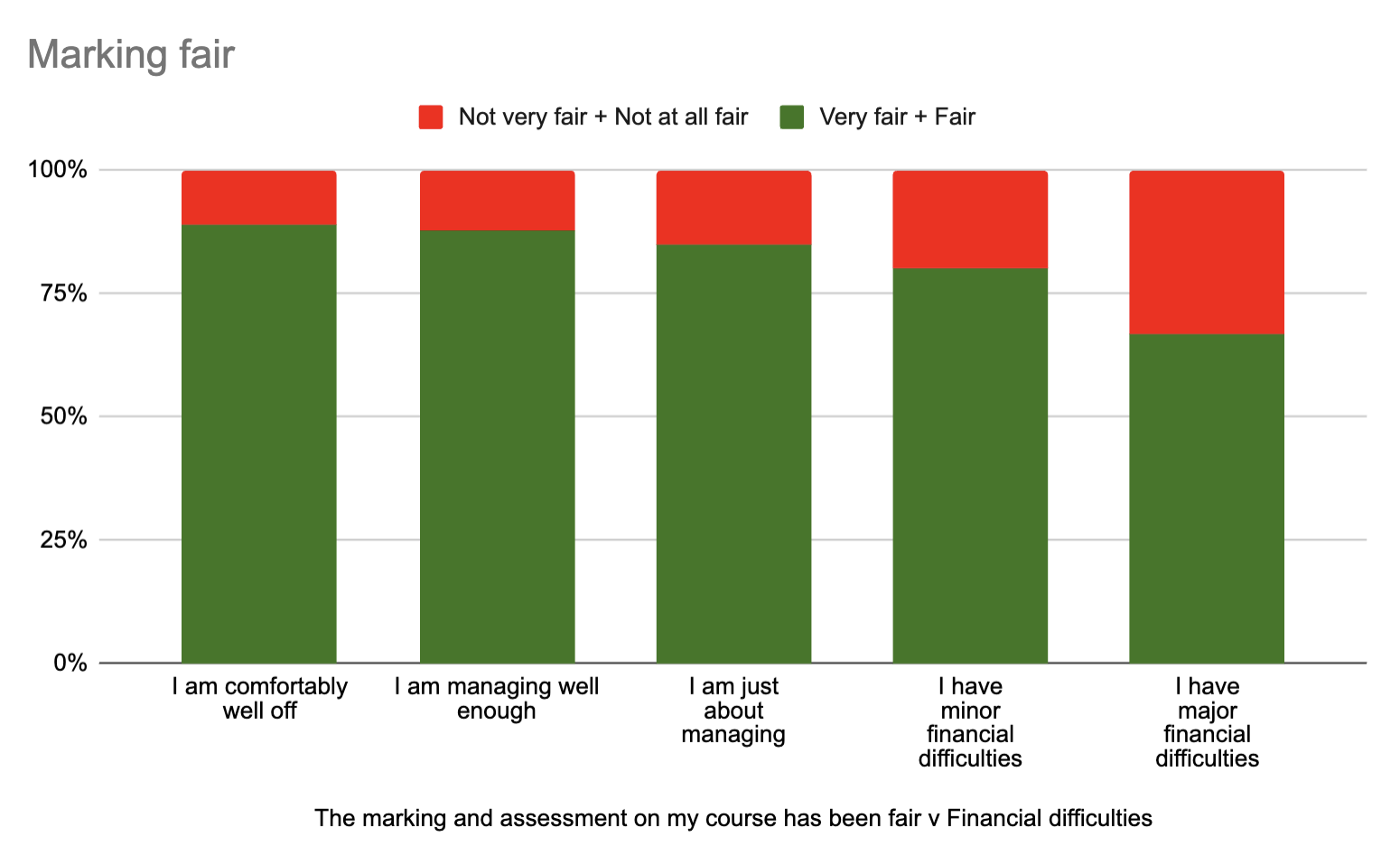

…and whether the marking and assessment was fair:

When we interrogated the free-text comments underpinning poor scores on assessment and feedback either because of inflexibility or a lack of understanding a year or so ago, students felt they had been unable to perform to the best of their ability and that hadn’t been taken into account by their university.

And those who described isolation were unsure of what was expected, not clear on how they might overcome it, and left to ruminate on poor marks without a way in which they might work with others to become more confident about trying again.

Perceptions of support for learning from academic staff differ by financial position too:

It all suggests that while there may be differences in need for and quality of support, students’ raw ability to even access the support on offer matters just as much.

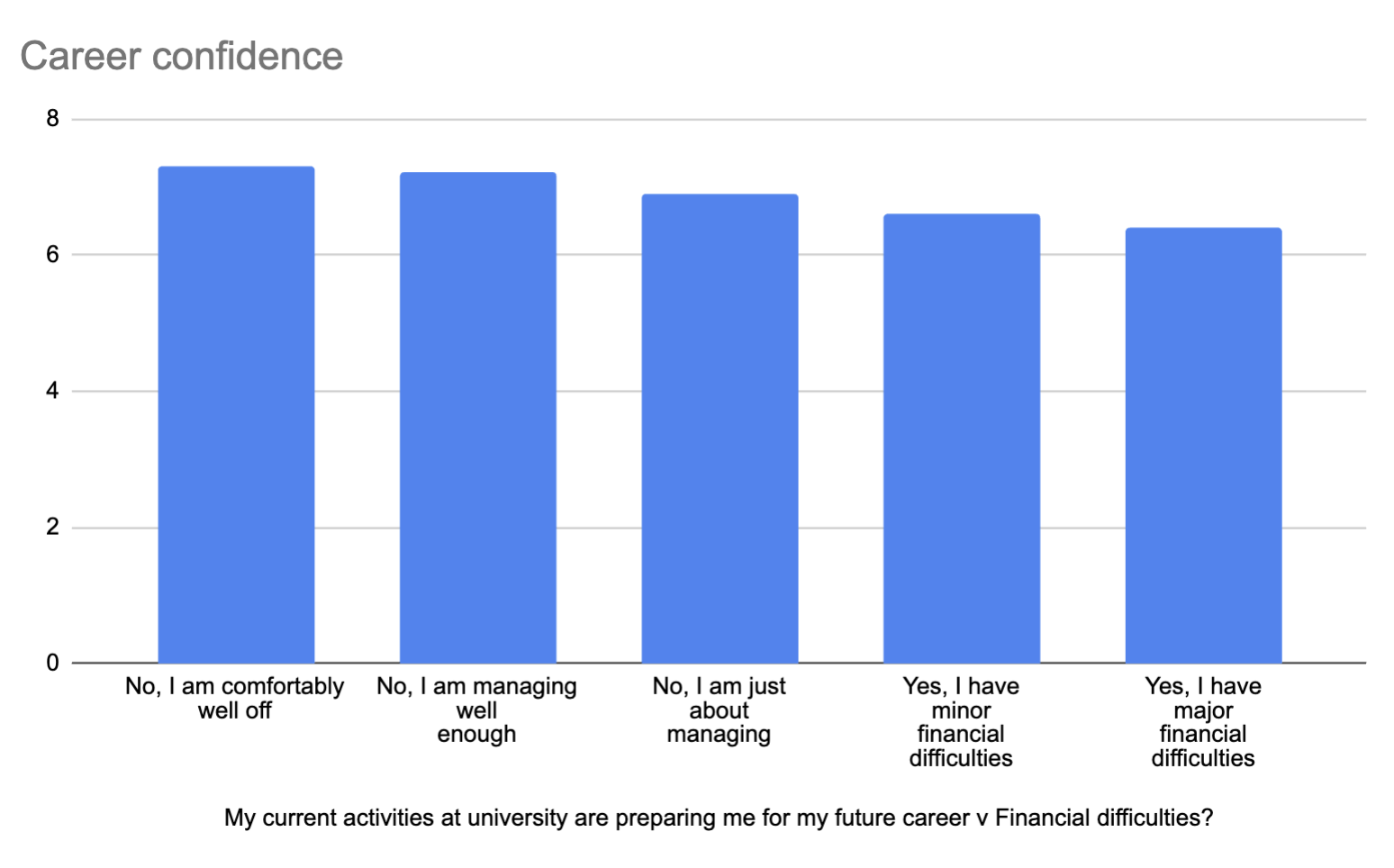

We can’t tell how well students will go on to do in the labour market – but we can get a sense of their own perception of preparedness:

If it’s the case that that perception then feeds through into actual labour market outcomes, we know what will happen next – by which time it will be too late.

Basic needs and minimum income

A large chunk of the way that the sector is judged – from both experience and outcomes angles – tends to assume that students are pretty much all the same, and that differences in those numbers are about what a university does and doesn’t do, and how it does it.

In HEPI’s work on a minimum income for students, the central concept is really one of equality – finding ways to “level up” those on low incomes so that we are confident that the outcomes they get from there are about their effort and ability rather than their bank balance.

So in our polling, we also wanted to look at whether those needs were being met – and to do so, we used a selection of the factors in the Staffordshire University/Purpose Coalition basic needs survey, and a couple of proxies for relative disadvantage – whether (home) students were entitled to a means-tested bursary, and social class.

If we look at who said they’d struggled with concentration over the past year due to lack of food, the differences are significant:

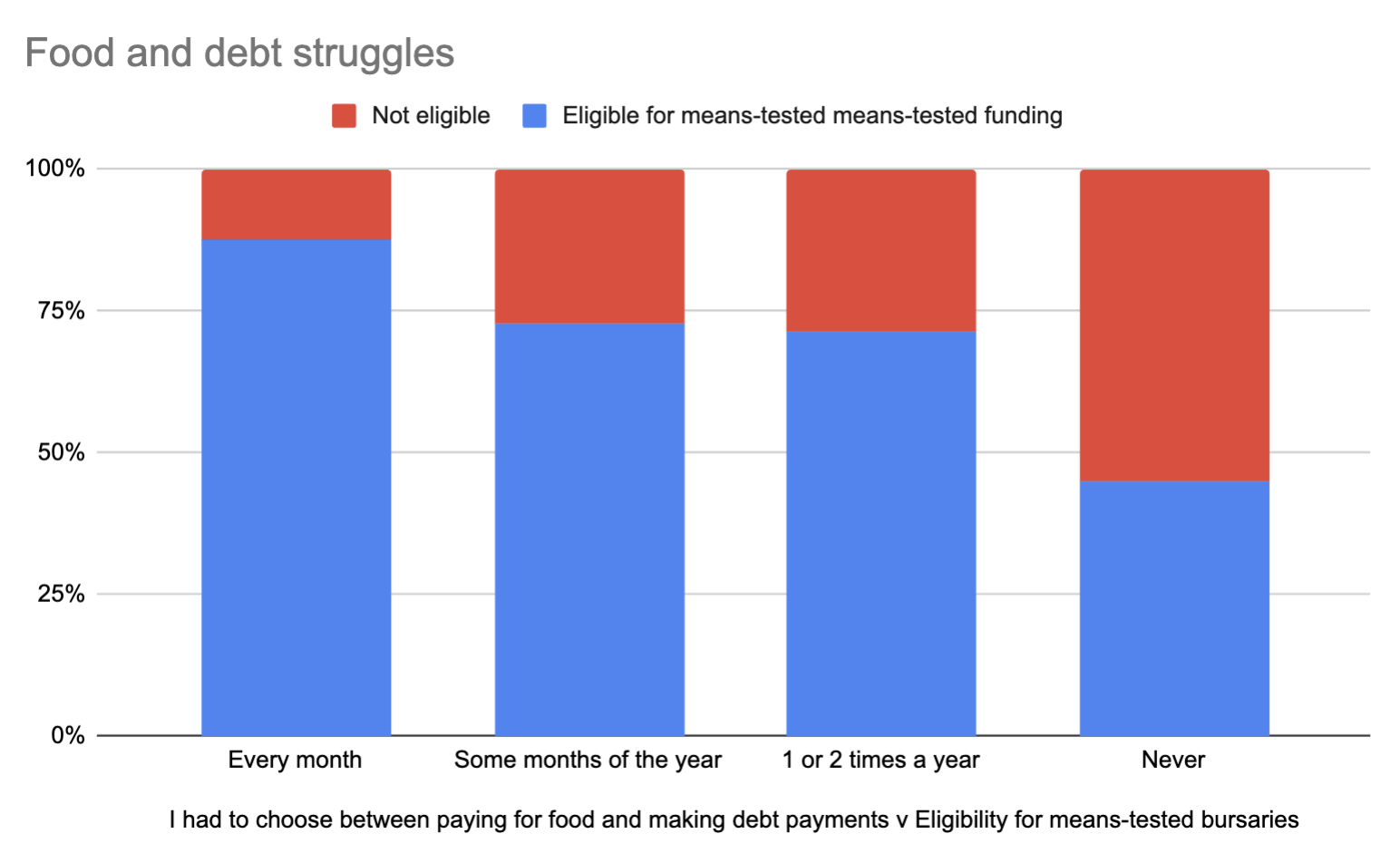

Choosing between paying down debt and eating also shows up important differences:

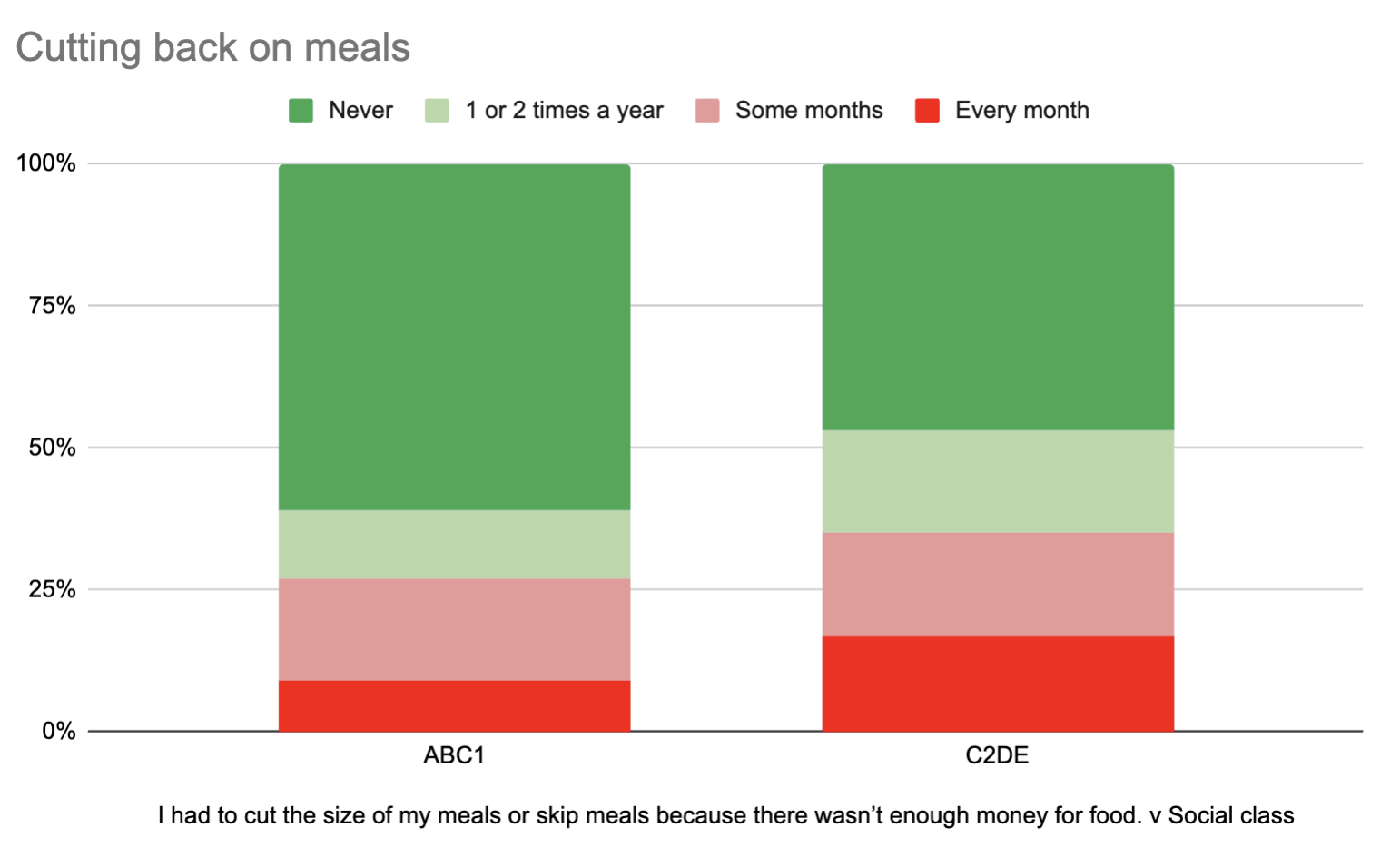

We can also look at the backgrounds of those who have been skipping meals:

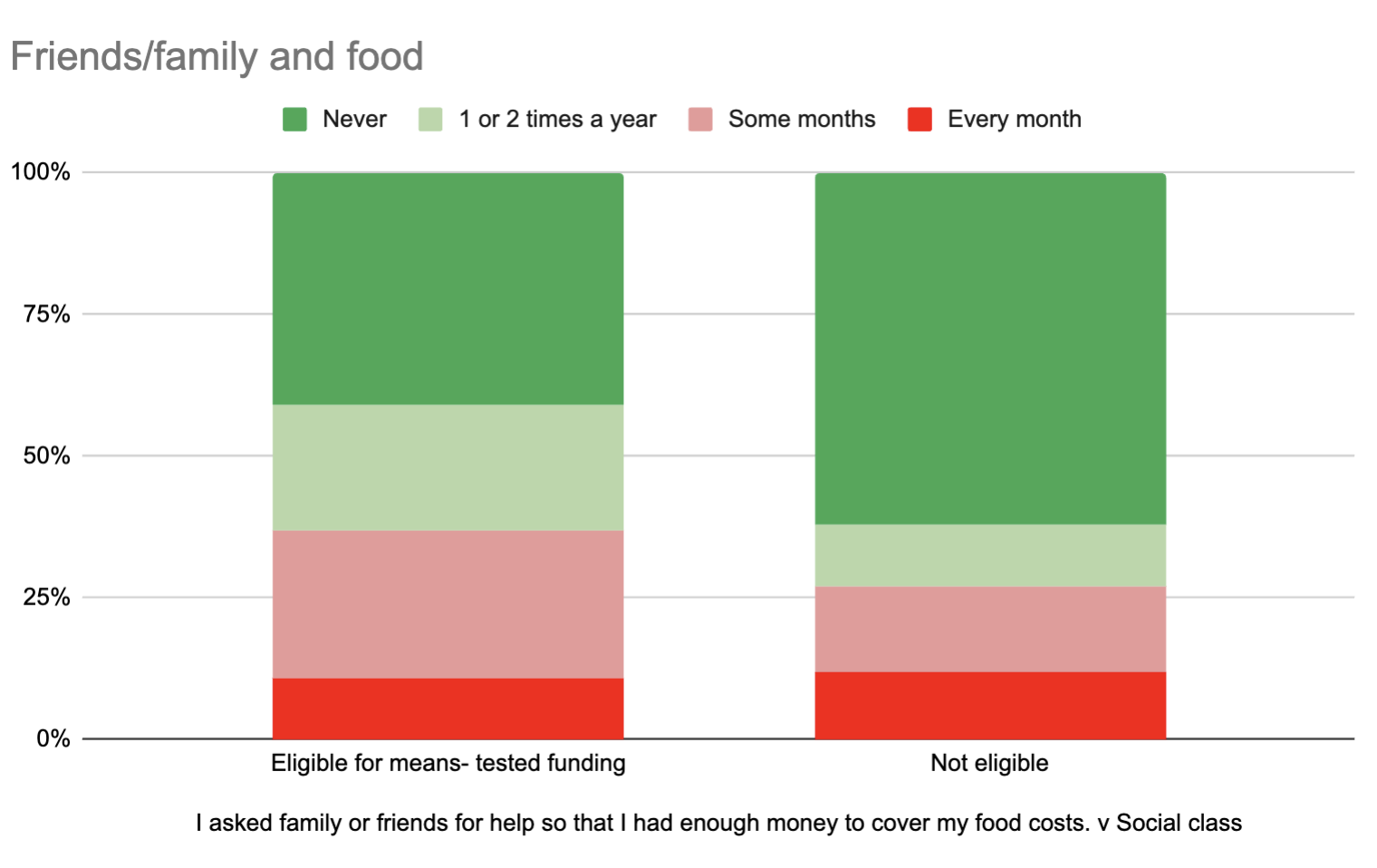

And who has had to ask family or friends for money for food:

Students were twice as likely to have cut down on personal hygiene and health items if they were entitled to a bursary; twice as likely to apply for student hardship if they were from social class groups C2DE; ten percentage points more likely to have cut down on their basic needs if neither of their parents went to university; and over a third of those from social class groups C2DE have been avoiding putting the heating on when it’s cold.

Global concerns

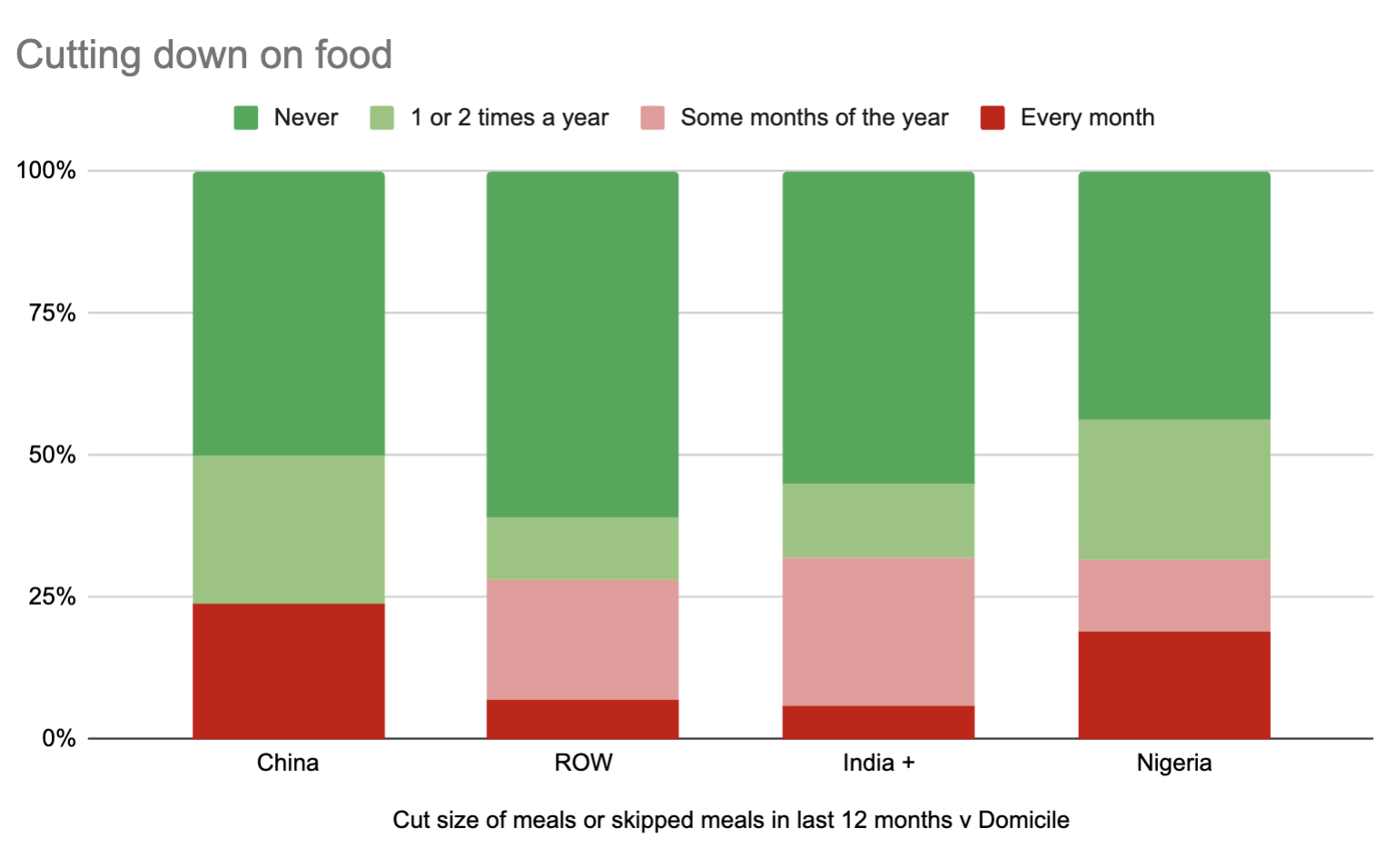

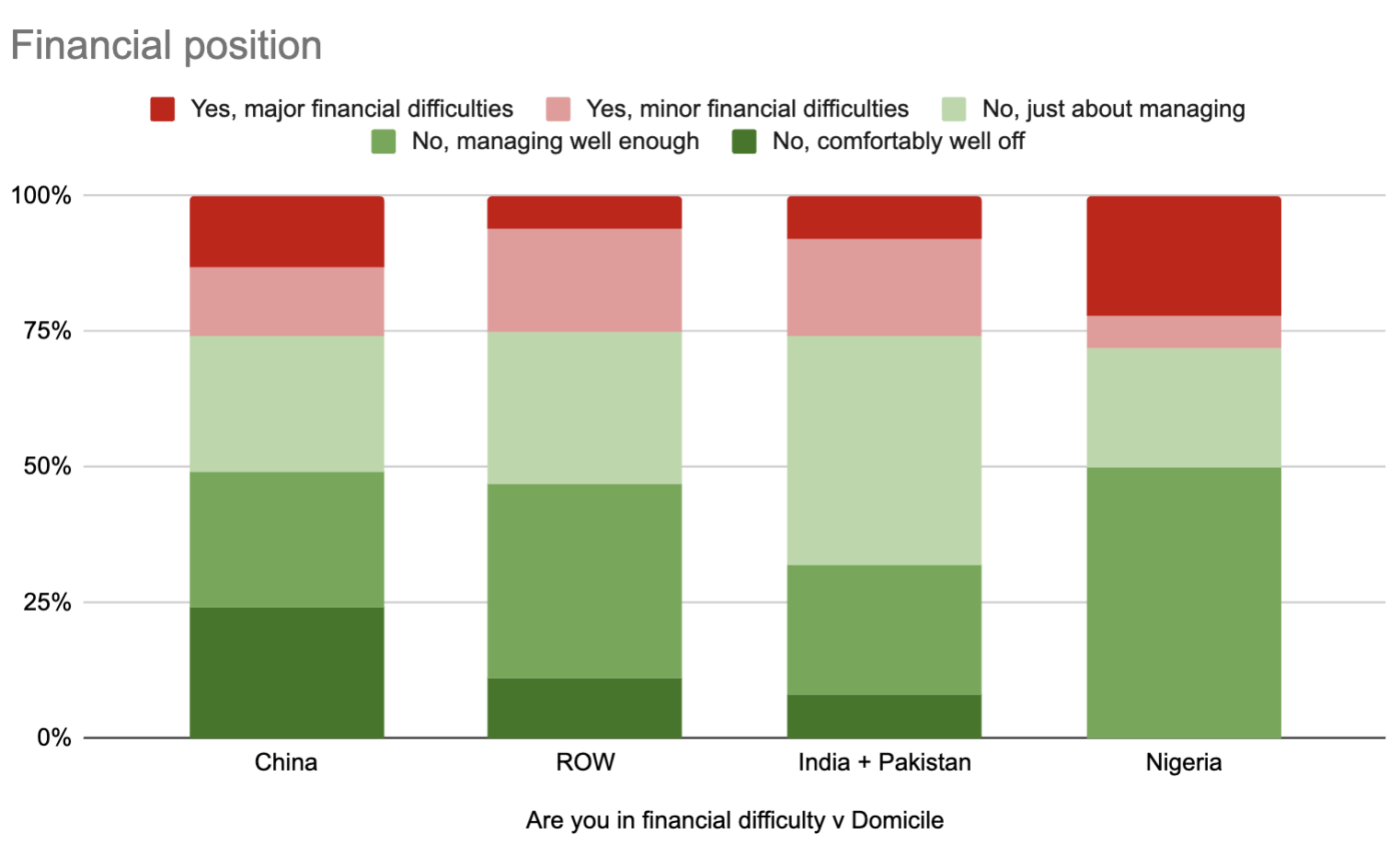

Those are the home-domiciled results. But we should also think about the different impacts of the crisis on international students. Here we’ve looked at differences between students from the big “markets” – China, India and Pakistan, Nigeria and for comparison, the rest of the world.

There are, for example, major differences if we look at who’s weighing up whether to pay the rent or eat:

Some students are much more likely to have eaten less than they should be:

Almost half of students from Nigeria have prioritised cost effective food over having a balanced diet, as opposed to just 14 per cent of those from China.

And if getting on for a quarter of students from Nigeria are saying that they have experienced “major” financial difficulties this year, no wonder many are struggling to pay fees:

Why this matters

I need not here reiterate the need to focus on reducing students’ costs and improving their maintenance support – although maybe I do given the number of cost-of-living strategy groups that have been wound down, the number of campus food initiatives that are being shuttered in the cuts, and the number of APPs approved last summer that have entitlement thresholds stuck at £25,000 and were seemingly approved by OfS without building in inflationary increases for the life of the plan.

This is a situation, lest we forget, that is about to get worse given that in England at least, September’s maximum maintenance loan is still going up by 0.5 percentage points less than Rishi Sunak’s now “normal inflation” – with the national parental income threshold still stuck at £25,000 too – as it has been since 2007. There’s something impossibly bleak about watching students’ unions move mountains to get students registered to vote, only to be repaid by political parties demonising or ignoring them.

In the year ahead, my big fear here is that for students in England, even loaning them more to live on would mean the model says that less will be paid back – spooking the Treasury. It’s not as if the terms and conditions of the loans they’re in could get much worse to notionally pay for it.

I also won’t go on again about the need to improve cost of living information for prospective students, and cushions for setbacks – especially for international students. It’s hard to believe that the figures we see here sum up experiences that they were intending to have or predicted they would have.

There have always been haves and have-nots, and there have always been studies that show us that the worst off end up with worse outcomes. For me, the reason that this stuff bears highlighting is that to some extent the sector, its regulators and policymakers imagine that once admitted, higher education represents a leveller – anyone can do well for themselves once they’re in. Hence much of the conversation is about who does and doesn’t go – and the way that “courses” or “subjects” somehow “dictate” outcomes.

Yet as a crisis settles into a new normal – of the worst off surviving, and the better off thriving – looking only at who the sector admits, who scrapes along to the end, or waiting for this stuff to show up in labour market outcomes in a few years’ time just won’t do.

These numbers tell us again that increasingly, governments’ failure to put some students in a position where their basic financial needs are met is harming both their ability to lead a normal and dignified life, and their ability to take advantage of that which their lifetime of debt is paying for. Even if they pass, they’ll fail.

There’s something to be said for the way in which both food insecurity and basic needs have become proper agendas over in the US. With some notable exceptions, there’s still far too much pretty-picture painting over the student experience in the UK, couched in a weird fear that admitting a particular provider’s students are going hungry will impact recruitment. Maybe that’s why there are strategic Basic Needs Centres over the pond, while here we’re more likely to see webpages telling students to seek out discounts.

But even bursaries, hardship funds, breakfast clubs and timetable intensification initiatives can only take students so far. Correcting these inequalities also requires urgent state action – and an honest conversation about the extent to which those providers with the most disadvantaged students can reasonably be expected to move money around to fix them.

The dilution of PSHE in school’s to become more a form of multi-gender indoctrination, something I’ve see change whilst being a school governor, so less time spent on the economic aspect, may well be part of this. Certainly our youngest had a better handle on finances than many whilst at Uni, and worked weekend night shifts in Saino’s to avoid taking the extra loans that eldest took which are still being paid off having been forced out of Uni by his employer/sponsor cutting staff including trainees.

The graphs and text are appearing out of sync / repeated?