The gender pay gap is a well-known phenomenon across all areas of employment, and many reasons are espoused for its existence.

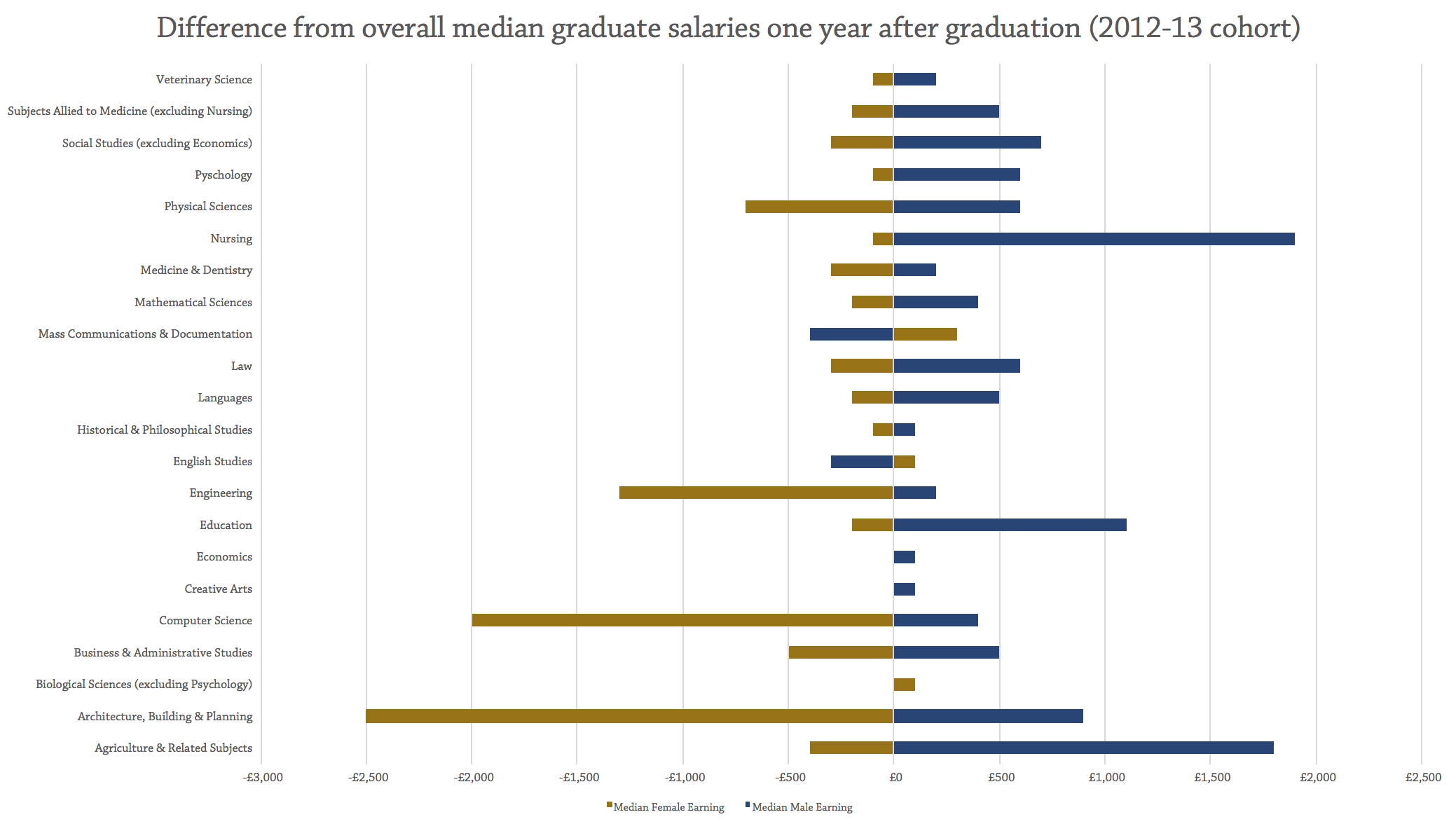

However, yesterday’s release of graduate salary data provides a shocking picture of the extent of the pay gap even straight out of university, and how different subject areas result in a diverse range of pay differences.

English Studies is the only subject where women’s earnings tend to exceed men (but only just) after five years. The DfE’s own analysis explains that “for all subjects except English Studies, male median earnings exceed female median earnings at more than 50% of institutions offering that subject. In twelve subjects, male earnings are greater than female earnings at more than 75% of institutions.”

Back in December, we found that the gender pay gap starts straight after graduation. We have been looking at the data across one year, three years and five years after graduation to understand the bigger picture. Here are some initial findings.

The good (ish)

Unfortunately, there are few subject areas where graduates resemble anything close to equal pay. In English Studies and Mass Communication and Documentation, the median salary for women is slightly higher than it is for men across the one, three and five-year post-graduation marks. In Economics, the median salary for men and women is roughly equal up until three years after graduation, but a gap of £3,000 emerges by the time we get to five years after graduation.

The surprising

One of the most surprising graduate pay gaps exists for Nursing graduates, a subject and profession dominated by women and with relatively little pay variance overall compared to other subjects. Still, only one year after graduation, men’s median salaries outperform women’s by £2,000, rising to a gap of £3,400 after three years.

Combined courses are difficult to measure as the data is so variable, yet prominent pay gaps exist in this area. In fact, the greatest pay gap exists here – with men earning £8,900 more than women after five years of graduating. It’s hard to hypothesise over why that is, given the broad range of courses that this category covers – unless Combined courses are a solid route into high level, high wage consultancy (perhaps).

Starting in year one

One of the most astonishing factors about the pay gap is how it begins instantly upon graduation in most subjects.

Numbers gaps matter, a bit

Following the nursing surprise, we decided to investigate if the different proportions of the genders taking different subjects made any difference to the graduate pay gap. It has been well documented that there are now more women entering higher education than men, and women tend to outnumber men in most subjects of study. But we found, that as with Nursing, most subjects that have more women than men graduates continued to show a pay difference. Nonetheless, as we can see from the table below, some of the highest pay gaps are in subject areas dominated by men, such as Engineering and Computer Science.

| Subject | # women | # men | % women | Difference between genders median pay, five years from graduation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineering & technology | 2125 | 11780 | 15.3% | -£4300 |

| Computer science | 1930 | 9350 | 17.1% | -£4400 |

| Architecture | 1970 | 5210 | 27.4% | -£3700 |

| Mathematical sciences | 1127 | 2930 | 27.8% | -£3200 |

| Economics | 1200 | 3015 | 28.5% | -£3000 |

| Physical sciences | 5190 | 7035 | 42.5% | -£2600 |

| Business and administrative studies | 15310 | 15855 | 49.1% | -£2800 |

| Biological sciences | 8255 | 8165 | 50.3% | -£700 |

| Historical and philosophical studies | 8160 | 7090 | 53.5% | -£800 |

| Mass communications & documentation | 4650 | 3680 | 55.8% | +£300 |

| Medicine & dentistry | 4805 | 3205 | 60.0% | -£2600 |

| Combined | 2690 | 1785 | 60.1% | -£8900 |

| Creative arts & design | 18735 | 11990 | 61.0% | -£500 |

| Law | 7730 | 4660 | 62.4% | -£3200 |

| Agriculture | 1210 | 645 | 65.2% | -£3200 |

| Languages (ex english studies) | 5715 | 2555 | 69.1% | -£1500 |

| Social studies (exc economics) | 16255 | 7255 | 69.1% | -£2800 |

| Subjects allied to medicine (Excluding nursing) | 11085 | 4360 | 71.2% | -£3600 |

| English studies | 7700 | 2765 | 73.6% | +£800 |

| Veterinary Science | 580 | 155 | 78.9% | -£1500 |

| Psychology | 9425 | 2025 | 82.3% | -£2000 |

| Education | 12225 | 1900 | 86.5% | -£2500 |

| Nursing | 11270 | 1060 | 91.4% | -£3300 |

What about university variances?

When you analyse and compare how different institutions’ do within each subject, we interestingly find substantial variations in graduate gender pay gaps.

For example, in Veterinary Science, a subject taken by a small number of students in a small number of institutions, the pay gaps vary wildly between graduates of different institutions. The University of Glasgow, for the record, did not have enough male veterinary graduates captured by the data to compare…

Institution Difference between gender salaries five years from graduation (Veterinary Science)

The Royal Veterinary College -£3100

The University of Cambridge -£1900

The University of Liverpool -£1600

The University of Edinburgh -£1000

The University of Bristol -£200

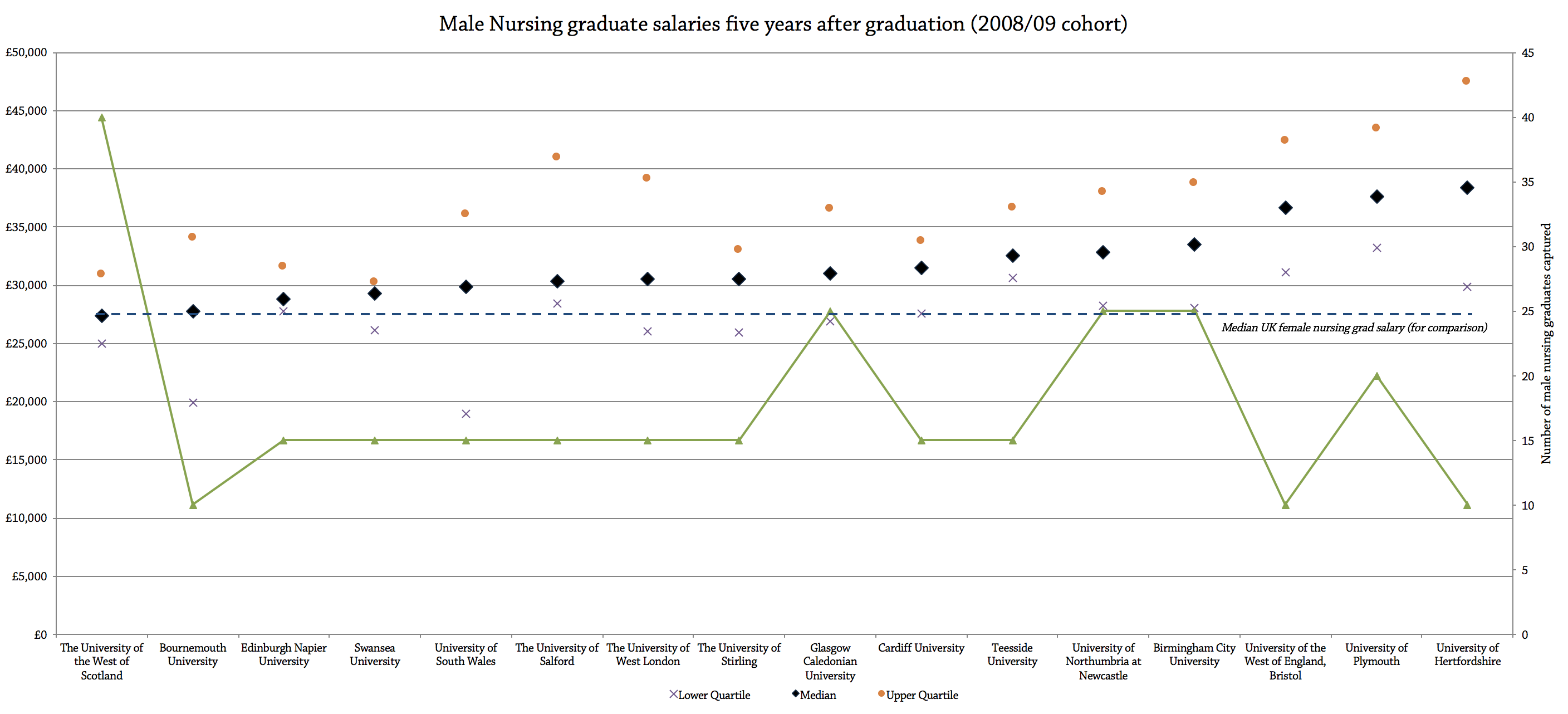

Evidently, it pays to be one of the small number of men studying Nursing. Perhaps most fascinating is that the upper quartile earnings for Nursing graduates at the University of Hertfordshire are a healthy £47,500 after five years.

Pay gap acceleration

Aside from English, Mass Communications, and Biological Sciences all subjects begin with a graduate gender pay gap from year one and increase over time. However, there are variations in the rate of that increase between one and five years after graduation, suggesting differing career paths for men and women graduates as they progress (or struggle to progress) up organisation hierarchies and salary scales. The gap increases 34 fold for Veterinary Science, 26 fold for Psychology and 18.5 fold in Subjects Allied to Medicine.

Explaining the gap

LEO data has its limitations, and there are challenges in using it to understand why there is a pay gap so early on in graduate women’s careers.

For vocational courses such as Nursing, it may be that men are less likely to progress directly into that vocation, perhaps using their degree as a base of more transferable skills to enter the private sector instead?

But for other subjects, there remains a question mark. The job market undoubtedly has a role to play. The voluntary sector is known to be where women are represented more than men and is likely to come with lower pay outcomes than for those graduates entering profit-making businesses. But there is a question about whether universities are failing to prepare women to enter well-paying graduate jobs with generous pay packets that appear to be more natural aspirations for men. Law is one such example of a subject area with considerable potential for high earnings and a notable gender gap. While the profession is known for its underrepresentation of women in senior positions, perhaps universities could play a more proactive role in preparing women to address the imbalance. Are universities failing to support women’s aspirations, so they are on a par with men?

The data suggests that universities should consider focusing some of their employability efforts on women specifically, particularly the possible role for careers services in tackling this problem. A lack of fully rounded LEO data is no excuse – the figures are clear enough to show that all in all, women are being failed by their universities in preparing them for the job market.

Unfortunately, yesterday’s LEO release does not enable us to explore pay differentials between ethnicities. However, last December’s release suggested that the gender gap is even more striking when race is factored in. Women from ethnic minorities fared exceptionally badly in earnings and employment outcomes compared to white men, particularly Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Black Caribbean women graduates.

It would be easy to argue that the LEO stats tells you more about employer behaviour than the role of higher education in employment outcomes, even if this is fundamentally correct. However, the immediacy with which the gender pay gap comes into play after graduation suggests that this is much a challenge for universities as it is for employers in our efforts to level the playing field.

It is worth noting that the LEO data is just for total earnings – it doesn’t tell us whether the individual is part-time or full-time or how many hours they work. In the 20-25 age group, 459,444 women worked part-time in 2011 compared to 323,993 men with 49,913 women working 49 hours or more compared to 125,843 men. http://www.jrf.org.uk/data/hours-worked-age-and-gender

But also worth thinking about why so many more women in the 20-25 age group are working part-time. Are they there by choice or because they are struggling to find full-time work? And if they are there by choice, is this because we still assume that women will be more likely to take on a part-time role due to, say, caring responsibilities? Similarly, it’s not easy to know whether women are not taking the jobs which ask them to work 49 hours or more through choice or because they are being passed over for these jobs in favour of men.

I agree Megan, I was just pointing out the limitation of the data set which prevents comparison of hourly earnings which is what the gender pay gap is typically measured on. There are other datasets such as ASHE and LFS which would help answer those questions.

It is difficult to know what universities could do to help women “address” the entrenched discrimination within the legal profession.