Trigger warning: contains detailed descriptions of sexual violence

To adequately tackle sexual violence, we need to know who it is happening to, who is perpetrating it, and where it is happening.

In the absence of national or institution-level data in this area, we decided to carry out a survey on gender-based violence and harassment at our university to build a clear picture of what students were experiencing to make the case for investing in prevention and response work and to understand how best to target such work.

In November – December 2020, a partnership between the students’ union and academic staff at an anonymised university in England surveyed 1303 students – predominantly undergraduates – drawing on internationally recognised survey instruments. The university provided an ethical review, and we worked with the student wellbeing service to set up appropriate support systems for respondents. The survey was sent to all students enrolled in the university by their Students’ Union Welfare Officer.

We had a response rate of 4.2 per cent. 725 respondents permitted us to use their data in publications – discussed here – and the findings from the full sample were presented to the university.

We have previously discussed the findings from this study on students’ levels of discomfort with professional boundaries with staff on Wonkhe. Here, we focus on the findings on sexual harassment and violence and later in this series, we will discuss findings on stalking and domestic abuse as well as rape myth acceptance.

Sexual harassment

It is important to understand the wider climate of gender inequality and sexual harassment within the university because these experiences can have a powerful impact on students’ ability to engage with their studies, work, and social life. This climate can also create a context where sexual violence and other forms of harm are accepted and seen as normal.

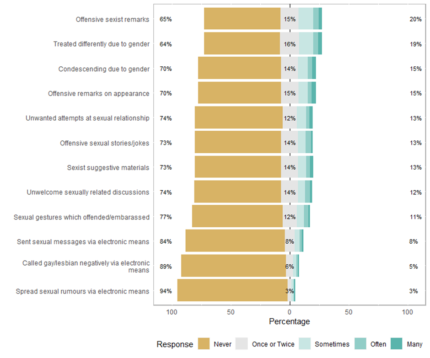

55 per cent of respondents had experienced some form of sexual or gender harassment whilst studying at the university, with 35 per cent reporting at least one experience and 20 per cent experiencing it more than once or twice. Gender was a predictor of being targeted for harassment, with women and non-binary students being substantially more likely to have been targeted. Women and non-binary students were also more likely than men to have experienced sexual harassment more frequently.

However, international students reported experiencing less sexual harassment than UK-domiciled students

Figure 1. Frequency of different types of sexual harassment and harassment on the basis of sex experienced by students.

Responses to sexual harassment

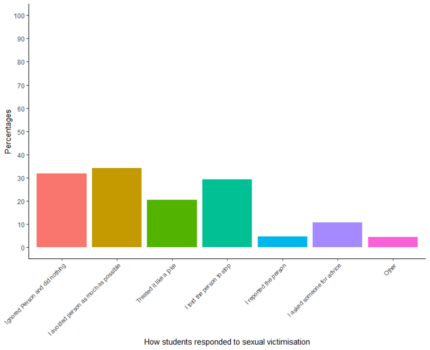

The university uses the ‘Report and Support’ system for reporting any form of harassment or bullying behaviours. This system allows anonymous reports and access support and links for making a formal report. Figure 2 shows the most common ways that students handled incidents of sexual harassment were to avoid that person in the future (34 per cent), ignore the person and doing nothing (31 per cent) and telling the person to stop (29 per cent). Only 5 per cent of those subjected to sexual or gender-based harassment indicated that they had reported this in some way. Low reporting rates have been found to be normal across wider studies of sexual harassment, but this rate of reporting is lower than some other studies have found.

Figure 2. Different ways of responding to sexual harassment.

Experiences of sexual violence

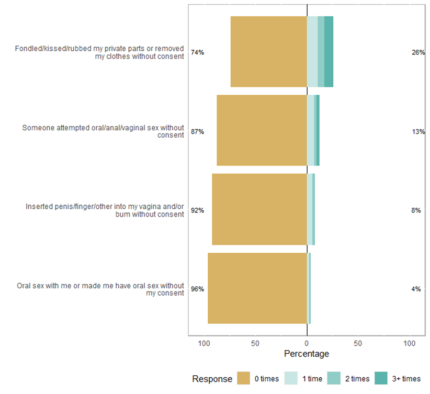

We also asked about experiences of sexual violence, including rape, attempted rape, sexual assault by penetration, and sexual assault.

Across all these experiences, 30 per cent of respondents had been subjected to sexual violence since enrolling at the university. Within this figure, just over a quarter of students (26 per cent, n = 145) who responded to the survey reported having at least one experience of their private parts being fondled/kissed/rubbed up against or having their clothes removed without their consent. Eight per cent (n = 56) reported that they had experienced a finger, penis or object being inserted into their vagina or bum without consent. In UK law, these acts count as rape or sexual assault by penetration.

Gendered patterns

Figure 3. Frequencies of different types of sexual violence experienced by respondents.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the survey asked specific questions about behaviours rather than using words such as ‘rape’ or ‘sexual violence’. This means that even if respondents didn’t think what happened to them counted as sexual assault, their experiences would still be counted. Women and those who identified as non-binary were significantly more likely to have experienced some form of sexual violence compared to men. As with the findings on sexual harassment, international students were less likely to have been subjected to sexual violence than home students.

We also looked at respondents who had been subjected to sexual violence more than once to see who was at risk of experiencing more incidents of sexual violence. Similarly, being a woman or a home-domiciled student were predictors of experiencing sexual violence more frequently.

Among us

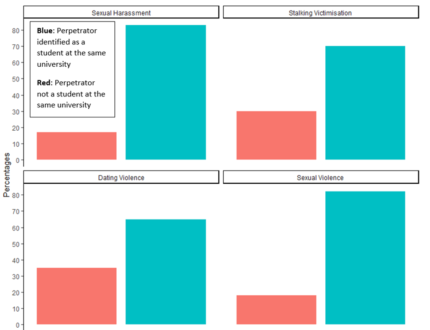

The findings on perpetration were perhaps the most striking. 83 per cent of sexual and gender harassment was carried out by another student studying at the university. Similarly, other students at the university were named as the person who carried out 82 per cent of reported sexual violence incidents, 70 per cent of all stalking victimisation and 65% of dating violence incidents reported.

Figure 4: Percentage of perpetrators of different behaviours who were described as students at the same university across the four different types of gender-based violence/harassment.

Perpetration was also much more likely to be carried out by men rather than women or non-binary people. When asked to describe who carried out the behaviour for the most serious incident they experienced, men were named by 82 per cent of those who experienced sexual harassment, by 89 per cent of those who were subjected to stalking, in 79 per cent of dating violence incidents and in 85 per cent of sexual violence incidents.

While most of these behaviours occurred off campus, a relatively large amount was still happening on campus. In addition, these behaviours tended to come from acquaintances or friends of the victimised person rather than strangers.

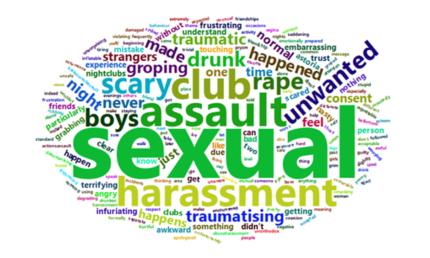

We also asked respondents to the survey how they labelled their experiences of sexual violence. This word cloud is made up of all of the comments that students made in response to this question. It points towards a wide range of descriptions, responses and emotions – for example, the word “normal” occurs next to the word “‘traumatic”.

Figure 5. How students described their experience of sexual violence.

Changing students’ behaviour

These figures are not a surprise. Recent articles on Wonkhe from academics at the University of Oxford and Ulster University/Queen’s University Belfast found similar proportions of students affected by sexual violence and harassment in their studies.

These findings show that it is predominantly women and non-binary students who are being targeted for a range of harassing and violent behaviours, both on and off campus. They also show that the vast majority of students perpetrating these behaviours are male students. Therefore, we believe that gender needs to be the focus of prevention programmes, and such programmes and campaigns must foreground male students.

The findings also show that most of the gender-based violence and harassment documented in this study was carried out by other students at the same university. This finding creates an important opportunity for the university and the students’ union to intervene in addressing this issue. Since it is students who are targeting other students, then it’s possible for activists, bystanders, and university-led programmes of work to intervene and change attitudes and behaviours.

These findings reveal the importance of carrying out institution-level surveys of gender-based violence and harassment. While there is, understandably, hesitancy from many quarters about carrying out such surveys, they can be carried out in ways that are safe and feel meaningful to respondents. We finish, then, with the words of one respondent to our survey:

I would also like to say that I really appreciated the survey as a whole; I feel it had exactly the right tone… the details of so many support systems and that you allowed for the skipping of uncomfortable questions was excellent.

In our experience, students want to be asked about and talk about sexual violence and harassment. We hope universities are ready to listen to what they have to say.

Full findings can be seen in our report ‘Is This Normal?’