Regulation of staff-student relationships has been discussed on and off for decades. However, it is rarely informed by any empirical evidence of what students feel would best support their learning.

It’s notable that the concept of “professional boundaries” – widely used in professions where practitioners work with adult clients or patients in occupations such as healthcare, therapy, or social work – is absent in discussion of higher education teaching and learning relationships.

Now that the Office for Students (OfS) is consulting on regulating universities’ in England’s handling of sexual violence and harassment, there’s an open question about whether staff-student relationships should be monitored, or prohibited entirely.

While a handful of universities in the UK do prohibit close personal relationships between staff and students, there has not been a general shift towards such a position, and the impact of such policies is as yet unclear.

It makes sense, therefore, to survey students to ask what types of behaviours they are comfortable or uncomfortable with from those who are teaching them. To date, we have carried out two such surveys in the UK. Both these studies clearly demonstrate that the vast majority of students – at least 75 per cent – are uncomfortable with staff having sexual/romantic relationships with students.

National data

In the first study, we explored students’ levels of comfort with different sexualised and non-sexualised behaviours from staff/faculty in our 2018 report, Power in the Academy, in partnership with the National Union of Students’ Women’s Campaign.

A new article we have just published in the Journal of Further and Higher Education carries out new analysis on the data from this study.

We outline scales relating to two areas of professional boundaries with staff/faculty:

- personal’ interactions – such as adding students on social media or getting drunk with students

- sexualised’ interactions – such as staff having sexual or romantic relationships with students or asking them out on a date

We then analyse how comfortable different demographic groups of students were with each scale.

Across both scales, women respondents were more uncomfortable than men. While this might be expected for sexualised interactions, it is notable that women were also more uncomfortable with personal interactions. For women and trans/non-binary people, the behaviours in the personal interactions scale such as private messaging on social media or arranging meetings outside the academic timetable could be experienced as boundary-blurring behaviours that may lead to sexual harassment, as we have outlined elsewhere.

More generally, as Fiona Vera-Gray explains in her study of street harassment Men’s intrusion, women’s embodiment (2017), women are socialised to be alert to higher levels of “intrusion” from men. Similarly, the lower levels of comfort with the “personal interactions” scale that women in the study report may reflect a lifetime’s experience of being alert to the threat of such intrusion’, as well as a much higher likelihood of having been victimised. As our study found, these points are also relevant to queer, trans and non-binary people.

As well as gendered patterns, differences across racialised groups were also statistically significant in relation to comfort with personal interactions. Both black and Asian students reported feeling more uncomfortable with personal interactions than white students.

While there are likely to be differences within and between these racialised groups that this study does not reveal, these findings need to be contextualised within wider research on the racial discrimination and inequalities faced by black and minority ethnic academic students and staff in UK HE, as well as in wider society.

They can also be explained through findings from focus groups on this topic with students from different identities, which we carried out for the Power in the Academy report. This revealed some of the reasons why black and Asian students had these concerns. For example, some participants felt that, for themselves, meetings in the pub or involving alcohol were inappropriate.

In addition, the lower levels of comfort among these groups with the personal interactions scale could relate to a preference for greater professionalism from teaching staff; for example, one participant in the Black students’ focus group commented that “a lecturer is not my friend and should not be telling me their personal information.”

A surprising finding is that there were no differences between postgraduate and undergraduate students’ attitudes across either scale. Indeed, levels of comfort with sexualised interactions were identical across the two groups. This is also notable as this survey purposively recruited a large sample of current postgraduate students (n=636) compared to undergraduate students (n=832).

This finding has important policy implications. While at some US universities, such as Cornell University, there exist different levels of regulation for sexual/romantic relationships according to level of study, with sexual and romantic relationships with staff prohibited for undergraduates but not for postgraduates, our data suggests that this approach is not justified by student attitudes.

Institution-level data

The study described above drew on data from a national survey. However, critics may argue that such attitudes will differ across institutions, and in order to implement relationship policies in an institution, local data on the institution’s own student population is needed. In order to explore this, we gathered data from a university in England in November-December 2020, as part of a wider survey on students’ experiences of and attitudes towards gender-based violence and harassment. The survey was sent to all students enrolled in the institution and 725 students – primarily undergraduates – completed the survey and consented to their responses being reported on publicly.

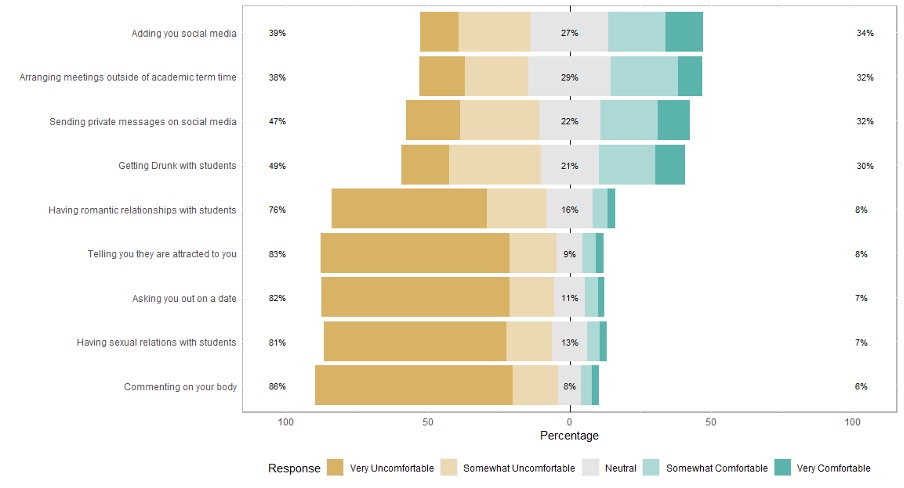

The findings are very similar to the national study described above. The graph below shows that the majority of responses to items on the sexualised interactions scale – staff telling students they are attracted to them, asking them on a date, having sexual/romantic relationships with students, or commenting on their bodies – indicated students felt very uncomfortable with them. 76 per cent of respondents felt somewhat or very uncomfortable with staff having romantic relationships with students, and 81 per cent felt uncomfortable with staff having sexual relationships with students.

In relation to personal interactions, while the levels of comfort were much more mixed, there was still a large minority of students who were somewhat or very uncomfortable with staff adding them on social media or sending them private messages on social media.

Gender was a significant predictor of comfort with sexualised interactions (the last five questions), with women students being substantially less likely than males to feel comfortable with sexualised interactions. Similarly, for personal interactions – which includes interactions online – women students and those who preferred not to disclose their gender were much less comfortable than male students. These findings are in line with those from our wider national study and demonstrate that, in this case, institution-level attitudes are very similar to those found nationally.

Where now?

These gendered patterns suggest that for all students to feel safe and comfortable in their teaching and learning environment, clear professional boundaries need to be in place. In order to address these issues, we have been piloting workshops on professional boundaries and recognising sexual harassment with postgraduate researchers, staff, and HR personnel at the University of York with support from the Enhancing Research Cultures fund and the York Graduate Research School.

Feedback has been very positive, with attendees reporting, not only that they have benefited from the sessions, but that they appreciate other students and staff being willing to show up to discuss this issue.

Overall, it is clear from both these studies that students are not comfortable with staff having romantic and sexual relationships with students, and that clearer professional boundaries more widely could contribute to a more inclusive learning environment for a range of groups of students. While there are undoubtedly challenges to designing appropriate policies in this area as well as resourcing work to embed any changes, our findings show that professionalising teaching and learning relationships in higher education are long overdue.

Genuine question.

If you ask anyone whether staff should have personal or sexualised relationships with students, I’m sure the vast majority would say no. They are picturing – as I would – the 50 year old lecturer and the 19 year old student, the power imbalance, etc.

But what happens when Dr Smith’s partner decides they wish to enrol for a PhD, having received a Master’s 15 years ago. They are both 40; they are in different disciplines, possibly different campuses. They have been married 12 years. There is no exploitation, no power imbalance – but it would definitely be a relationship between staff and student. Do we just have to say – well, either he can’t enrol or she has to quit? I know some US companies did that when employees entered a relationship.

This is often swatted away as being ‘the exception’ and ‘unusual’ – yes, agreed, it is both of those things. But it’s a consequence, foreseeable, and we should own it explicitly if we endorse the policy

Similar example to above (well made point, thanks Jon). Two friends of mine were students together and in a relationship. They then graduated. She went on to do a PhD, he went on to become University staff (professional services, not teaching). The relationship continued, but was declared to the University. It didn’t feel in any way inappropriate.

Simples. You put a ban on initiating relationships and accept that pre-existing ones will emerge in the two roles.

That’s not that simple – what if in CC’s case the two friends had started their relationship after graduation? Not hypothetical; I met my partner about 20 years ago while I was a new PS staff member and they were a student. We originally met through a mutual friend outside of the university context, the age difference between us is tiny, the “banned” part of our relationship didn’t start until we’d known each other for a few years already, and I don’t think we ever interacted with each other in a workplace context. Indeed, it was a pure coincidence of which job offers came in when that I was working at the uni at all, rather than for another local employer.

It seems utterly arbitrary that this “simples” policy would:

– have allowed the relationship if I worked for City University rather than University of City (or for University of City’s outsourced rather than in-house provision!)

– have allowed the relationship if it had started at a slightly different time (especially if – in letter but not spirit – it had been in the gap between their masters ending and their PhD starting)

– potentially, depending on how poorly the definitions of “staff” and “student” have been written, allowed the relationship to start after they got a homework marking contract during their PhD, but not before

So obviously, while it no longer affects me personally at all, I do inevitably take it a bit personally that this is all apparently “simples” and can be sorted out without either banning a whole bunch of relationships like mine was … or even PGR-PGR ones if the definitions aren’t handled well … or leaving so many loopholes that Prof Creepy can also use them and the policy is worthless … or not actually addressing the fact that hiring Prof Creepy was a problem to start with even if it is only the junior postdocs the university allows them to prey on. Show me the properly-drafted text of a policy that addresses all that and wouldn’t have made my relationship collateral damage, and you’ll have my full support. Handwave that of course it wouldn’t have been an issue for you, that’s not what it’s targeted at, and I’ll be instantly suspicious.

Sorry to be (very) late to the party. Will this one do: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/human-resources/personal-relationships-policy#Relationships%20between%20Staff%20and%20Students