The motorway is about to fill up with cars heading off to universities full of eager young minds and everything but the kitchen sink.

Being a modeller at heart I have been known to refer to universities as “black boxes”. When students arrive on their first day we know some things about them – their educational background, their UCAS tally, their ethnicity – then three years later they pop out again, hopefully with a degree (which we know about) and ideally with some life skills (which we know much less about). What goes on in-between is often a mystery.

This lack of knowledge doesn’t help anxious first year students who have no idea what awaits them when they walk through the door. It’s amply illustrated by these quotes from second and third year students in a Learning Gain focus group, talking about what they thought university would be like:

- “I thought it would be like you learn this in a lecture and then you write an essay on it….It is very independent in the way that you learn things and write essays. I didn’t realise it would be like that. “

- “I thought it would be like coming to uni and doing one subject and there are actually so many aspects: it feels like loads of different subjects.”

- “I thought it was going to be a massive party because you see students going out and getting drunk all the time on TV.”

Black boxes don’t help new academics wanting to design courses that will help develop academic and transferable skills. They don’t help careers advisors trying to work out how to get students to think about their futures. They don’t help local employers keen to employ graduates but not knowing what to expect from them. And they don’t help those working to improve quality and transparency across UK higher education.

The Office for Students (OfS) Learning Gain pilot projects will help us build further understanding about what and how students learn at university. One aspect of the University of Lincoln and University of Huddersfield pilot is to explore new students’ perspective on their expectations, concerns and experiences as they start university.

Student self-assessment

One of the tools used in Lincoln’s learning gain project is a preregistration self-assessment survey called GetSet which uses a Likert scale to assess students’:

- Confidence in relation to a number of academic skills

- Expectation in relation to what and how they will learn

- Previous experience of academic competencies such as working in groups, managing time, taking notes

- Thinking about their future careers.

Completion rates were strong with over 65% of first years completing it (~2,500) and over 500 second and third years. The quantitative data is interesting enough, but perhaps most enlightening are students’ free text answers to the question, “Is there anything you would like to raise as a concern about your confidence relating to academic activities before you begin your studies with us?”.

What did we find out?

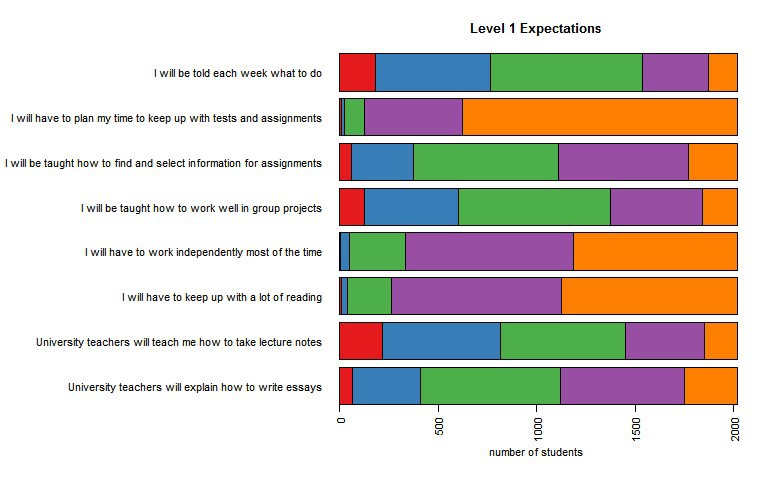

Unsurprisingly, students are least confident about giving presentations and critical thinking, and almost one in five raise concerns about presentations. But most troubling is that first year students don’t really know what, or how, they will be taught at university. This table shows wide neutral response bands for the expectations questions.

Figure 1: First year’s responses to the GetSet Expectations questions

This is especially concerning for students with mental health issues, learning difficulties or additional needs. Some 10% of students who responded to the question identified issues around learning difficulties and another 9% around anxiety and mental health. Others raised concerns around writing essays, time management, subject knowledge, and practicalities like how to access support. How can students make informed decision on whether to go to university if they don’t really know what to expect when they get there? By addressing some of these concerns early on we can do much more to ease transition and cut early dropout rates.

How does this benefit students?

Doing this sort of work offers the potential to share headline results with students and academic staff at the beginning of term. The message is simple – that it’s ok to be worried, and there are many others worried about the same things. There’s also reassurance that although things might seem scary at first, when you look back you will see the benefit. For example, despite concern among first years about giving presentations, by second and third year, 28% of respondents identified it as the activity that gave them the greatest boost in confidence.

Understanding more about students’ concerns helps inform academic and professional skills course development. The self-assessment process itself can be useful in outlining to students the type of skills they should be developing, and revisiting the same assessment each year is beneficial. However, to be of real value it needs to be followed up with targeted opportunities to develop these skills. This has been a sticking point with our wider learning gain activities; formal opportunities have been offered e.g. talking to personal tutors or attending targeted careers and employability sessions, but take up has been variable. Work is ongoing to explore the most effective way to present this information and make sure it has an impact on student experience.

Making it work

We have learned some things along the way. Using clear and accessible questions and providing guidance on how to self-assess skills is important. Getting the survey out as soon as possible to new students is also crucial – keen first years are more eager to complete it before they start. Turning the results and feedback around quickly means that students are more engaged and staff better prepared to support students right from the start of term.

The richest learning is based on analysis of free text data to optional questions. In the era of big data, how valuable is this information and how much time do we have available to process it to gain a deeper understanding of our students than a simple Likert rating can provide?

Not foolproof

There are a number of these type of self-assessment tools being used across the sector and our version is not unique. It’s also clear that self-assessment is not foolproof. The literature and our experience highlight that students often struggle to self-assess their skills. Self-assessment is not a skill that is taught in schools – but by introducing it right at beginning, students can be encouraged to continue being proactive in their skills development throughout their education.

There is also the oft-cited concern around survey fatigue. But a pre-registration survey such as this which offers multiple benefits for students, universities and the sector more widely has an important place within the raft of surveys confronting students.

There remains an open challenge, though, of how to ensure students meaningfully engage with both the survey and crucially their own skills development during their academic careers.