I’ve written here before on several occasions about the place of administrators (often called professional services staff but also, unfortunately, ‘support staff’ or ‘non-academic staff’) in UK universities. Much of this commentary has been about the role of professional services and the nature of their contribution to institutional success together with a general defence of value and some modest requests for recognition.

There is still though, sadly, in some parts of HE a division between academics and administrators, and we do sometimes see evidence of an ‘us and them’ culture (despite the enormous persuasive power of a couple of my earlier blogs on Wonkhe).

The academic “at”

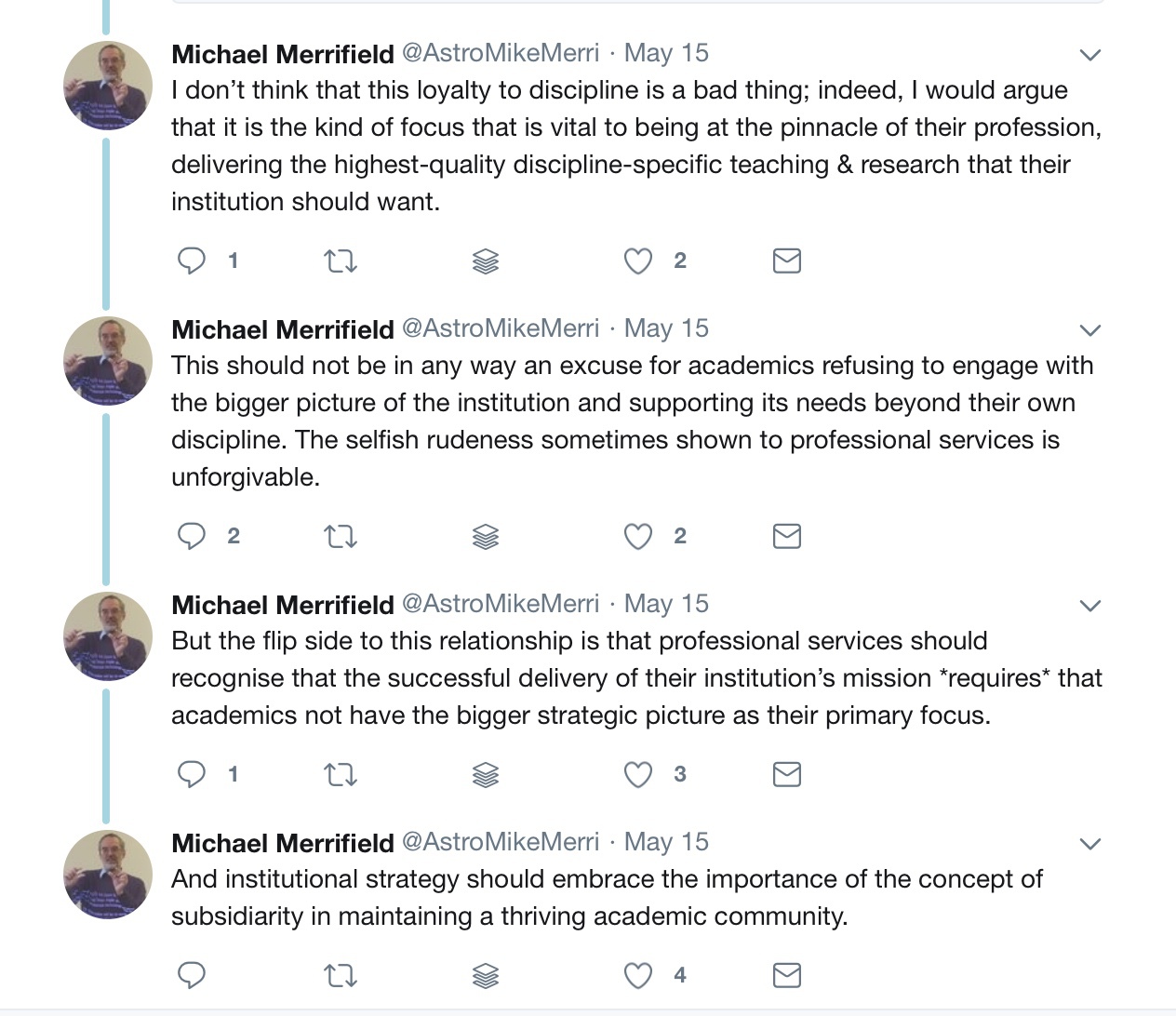

In a recent post here on some new research on the career trajectories and the crossing of academic/administrative boundaries at the level of senior professional leaders the ways in which professional services and academics engaged was also noted. One comment in the report highlighted a distinctive point:

But as one of my academic colleagues observed this demonstrates a key point about what he describes as “the ultimate source of tension between academics and professional services.”

He went on to note:

This seems to me to be a very good point. It is a two way street and, in order to do their best work, most academic staff need to focus on their discipline. Professional services staff have to recognise this, work with it and embrace it as fundamental to institutional success.

But I fear that there is still evidence of the ‘us and them’ culture which leads to administrators sometimes being targeted as being ‘first for the chop’ in times of financial crisis. It also sees professional services staff sometimes being viewed as if they were servants rather than as genuine colleagues.

Proof of work

I had hoped this kind of attitude was dying out but it does seem that it can still be found in some parts of higher education as this latest exciting innovation demonstrates.

It seems there is a new university which intends not only to reduce administrative costs but apparently dispense with university administrators altogether. As David Kernohan recently reported here on Wonkhe, Woolf University is intending to exploit cutting edge blockchain technology to reinvent the university for the future:

Woolf is meant to disrupt the economics of higher education and provide new opportunities for both students and academics. Blockchains with smart contracts can automate administrative processes by using the WOOLF utility token, thereby reducing overhead costs. Students can study with lower tuition, and academics can secure their salaries. Woolf will also seek to partner with existing universities, helping them to implement aspects of the platform, reduce their administrative costs, and free up resources for their core educational mission.

Blockchain has offered many a panacea of late and this one surely is among the least credible. As Kernohan notes:

Startlingly, one stated end goal is to employ zero administrators, with processes managed by “smart contracts” – self-actualising units of code that interlink to record student progression and release payment to academics. And, although an individual Woolf college may choose to subject itself to the rigour of joining the regulated higher education sector in any given jurisdiction, this is by no means required in all cases.

As he goes on to observe, the idea that even the lightest touch intervention by the new Office for Students (or indeed many other aspects of university operations including quality assurance, student recruitment, student welfare or administration) could somehow be handled in an entirely automated way is perhaps a tad optimistic.

Open season

Nevertheless, this is very much in the vein of similar forays against administrators such as this tirade which I quoted here a while back

Then there is the administration. Leaving aside the widely pilloried and Sisyphean administrative exercises known as the research excellence framework and now the teaching excellence framework (TEF), to put it simply we have in recent times witnessed an administrative coup in UK academia. In an article focusing on the University of Oxford but painting a picture that will be familiar to most academics, The Spectator wrote that the “university’s central administrative staff is now almost three times what it was 15 years ago. There was no similar increase in full-time academic staff, the people who teach students or do research…”

Even allowing for the absurd hyperbole of an ‘administrative coup’ the author of this piece was clearly unable to distinguish between externally imposed regulation and assessment and the administrative support required to enable universities to deal with this bureaucracy, protect academics from its worst excesses as well as helping keeping everything else moving. And the Spectator item goes even further:

And the problem of burgeoning bureaucracy helps explain some worrying trends, foremost being a perceptible decline in academic standards over time (it’s evident in grade inflation; there are three times as many Oxford Firsts now as there were 30 years ago).

There it is then, not only are there too many administrators where there should be academics, they are responsible for grade inflation and the decline in academic standards. Back to the original THE piece I quoted which really ices the cake:

I’ll merely point out that an increase in administrators – lovely and well-meaning as most of them are as individuals – naturally does not do what you might naively expect, ie, take care of the administration so that academics can focus on academic work. No, instead it breeds ever more complex administrative mazes that are not just difficult to navigate but are de facto becoming the main part of the job. Kafkaesque would not be pushing it too far by any means.

It really is a special achievement to be quite so exceptionally patronising and professionally insulting in so few words. Fortunately, others were equally appalled by this including the very lovely Charles Knight who sought to stress how much he loved administrators and noted the vital role they played in many aspects of university life before concluding:

The real reason I love my administrators, however, is that I truly have never felt that at Edge Hill University there is this hard divide between academics and administrators – and that doesn’t just refer to processes; it’s about culture and values.

Stepping out of the “back office”

Many years ago I wrote a piece for Times Higher Education on my unhappiness about the term “back office” and the often casual, unthinking use of it in order to identify a large group of professional services staff who play a vital role in the effective running of universities but who often find themselves treated as second class citizens. These administrators are often viewed as if they were Victorian servants who generally remain below stairs, undoubtedly fit into the category of “lovely and well-meaning” and are often targeted first when savings are required.

Leaving aside the fact that many professional staff are unequivocally front-line, the idea that the other staff who help the institution function and who support academic staff in their teaching and research are merely unnecessary overheads is just not right. If academic staff are to deliver on their core responsibilities for teaching and research it is essential that all the services they and the university need are provided efficiently and effectively. There is not much point in hiring a world-leading scholar if she has to do her all her own photocopying, spend a day a week sorting out visa issues or overseeing and renegotiating software service contracts because there aren’t any other staff to do this work. These services are required and staff are needed to do this work to ensure academics are not unnecessarily distracted from their primary duties. Although provision of such services is not in itself sufficient for institutional success, it is hugely important for creating and sustaining an environment where the best-quality teaching and research can be delivered.

“Barbarous, semiliterate prose”

For some though, this argument doesn’t cut much ice. Terry Eagleton recently penned a piece for the Chronicle in which he lambasted many aspects of university management, and accused HE leaders of conducting a technology-driven purge of books and paper. In his view institutions have a

Byzantine bureaucracy, junior professors who are little but dogsbodies, and vice chancellors who behave as though they are running General Motors. Senior professors are now senior managers, and the air is thick with talk of auditing and accountancy. Books — those troglodytic, drearily pretechnological phenomena — are increasingly frowned upon. At least one British university has restricted the number of bookshelves professors may have in their offices in order to discourage “personal libraries.” Wastepaper baskets are becoming as rare as Tea Party intellectuals, since paper is now passé.

Then he goes further, much further:

Philistine administrators plaster the campus with mindless logos and issue their edicts in barbarous, semiliterate prose.

Nice. I wonder what he thinks about the Woolf University concept.

Anyone who sees administrators either as merely lovely and well-meaning or as semi-literate philistines but in either case ultimately expendable really does need to think a bit more about how universities really work. We are all pulling in the same direction and administrators, whatever their roles, are dedicated to enabling institutional success not preventing it.

Dispensing with administrative staff altogether as those enthusiastic blockchain disruptors envisage goes well beyond even this of course, but we do need to move away from the now very dated ‘us and them’ attitude and that requires a different way of looking at how we all work together in our universities.

Eagleton:

“Philistine administrators plaster the campus with mindless logos and issue their edicts in barbarous, semiliterate prose’

Self-reflection might be required in the case of the latter characterisations before criticising the prose of others.

Good points as always – but could I make a gentle plea for Knowledge Exchange to be included , both academic and professional services staff? “If academic staff are to deliver on their core responsibilities for teaching and research” , otherwise we poor professional services staff working in KE will feel doubly in the shade 🙂

The single worst experience I have ever had working in HE was in admissions for a University in Greater Manchester . I was covering Social Work and had a fantastic and incredibly supportive Admissions tutor who arranged for me to go and sit in on a selection interview to learn more about the process that followed after my “first sift”, with the idea that I would gain more insight into what makes a successful applicant and improve my understanding.

Unfortunately, I ended up being a lamb to the slaughter…I ended up sitting in on a group interview conducted by one of the professors and a senior academic who, for whatever reason, decided that I actually had been sent from central administration to audit their practice and who therefore decided to go on the front foot by being openly hostile towards me, grilling me on my social work experience (I had none), asking me why I thought I was sufficiently qualified to do my job and, as they walked away from me down the corridor, loudly discussing how immensely concerning it had been to meet me (at a volume that I was of course able to hear, a fact which would not have been lost on two highly qualified social workers).

This was admittedly a bit of an outlier in my experience since, I’ve been very lucky to work for and alongside some incredibly humble, considerate and professional academics, many of whom have openly deferred to my area of expertise when appropriate and few of whom have made me feel like an inconvenience, irrelevance or even an enemy. But that first experience was an incredibly bruising one and certainly gave me a taste of just how toxic the relationship between “us” and “them” could be…

Enjoyed this Paul. Indeed, the division is problematic and the construction of classic stereotypes by both sides of the divide are unhelpful and make it more difficult to overcome the antagonism. The snobbery of some of the academic (Left) to see professional staff as merely faceless cogs of the neoliberal machine rather than as workers with their own set of issues and pressures is counterproductive when it comes to building solidarity against attacks on pensions and contracts, or indeed in bringing people around to a different vision for higher education. Perhaps, dare I say it, this comes from a misinterpretation of Marx’s polemic against the Prussian bureaucracy in his Critique of Hegel’s “Philosophy of Right” as being a critique of bureaucracy or bureaucrats as such. Perhaps not! Ultimately, the maintenance of an ‘us’ and ‘them’ merely essentialises the otherness of the two identities and only helps to reinforce the logics of marketisation that academics are against.

I would add, however, that some executive teams and university Councils help to maintain the asymmetrical relationship as a result of their responses to market and funding pressures. In situations of financial uncertainty, professional services are often first to see cuts or freezes. The pressure to keep up staff-student ratios and expand student numbers will mean that some institutions look to increased resource for academic staff first, before looking to meet the increased administrative demand on an institution. Sometimes there is an expectation that increased student numbers can be met by increased efficiency in professional services rather than accepting there are real issues with resource and workload that make university administration hellish and ultimately lead to lower staff productivity and declining quality of student and staff experiences.

Apologies for the KE omission George.

That is an awful experience Graeme but glad it is an outlier. I’ve had one or two like that including for the reasons outlines in the comment from Adam Wright here. But fortunately they have also been very unusual.

A very thought provoking article Paul and one which certainly exposes some unhelpful and unhealthy attitudes across the sector. My experience has led me to conclude that there are three particular practices which reinforce the divide:

1) Academia being treated as the ‘production environment’ and normal business practices can be imposed. It isn’t and they can’t. There needs to be recognition that academics think, operate and work differently to any other sector. Unless this is grasped, there will always be scope for potential conflict.

2) Academics and professional services staff being considered as homogeneous groups rather than individuals. This makes ‘them and us’ easy to define and is convenient. Some academic colleagues want to engage deeply in administration, others don’t. Is this a bad thing? Not necessarily, it’s just different horses for different courses.

3) Ego. Academics can have large egos – this is inevitable when dealing with experts. The real problem arises when all academics are treated as though they have large egos, even if that’s not the case. It creates distance between individuals, even when none really exists.

If we accept our colleagues on either side of this debate as people doing a job that’s different to our own, we’d see less of this damaging behaviour.

For a number of years the tide did seem to be changing with significant respect yet opportunity for healthy challenge amongst colleagues in whatever roles in HE. One growing divide is the consideration of students solely as academic learners by some, not acknowledging their role in the wider community (and the support for their wellbeing as well as other aspects required to ensure they can fully access learning). Additionally, while it is important to harness ‘specialist’ expertise from a range of other sectors, there are reductions in ‘administrators’ who truly know and understand the HE sector and needs of the variety of diverse communities within it causing further agitation between this dichotomy.

This feature is predicated on a dichotomy. But there seem to be four main groups:

A) “remote” support staff who have low or zero contact time with students

B) “remote” academics who have low or even zero contact time with students

C) “involved” support staff who have significant contact time with students (eg counsellors)

D) “involved” academics who have significant contact time with students

A may be in conflict with C and D.

B may have tensions with D (?).

C and D generally get along (!?)

Having navigated HE and external partner relationships for the last 12 years or so, I have found academics to be quite engaging and receptive once they understand that we are both experts towards the same goals. Its up to both parties to develop that trust and confidence. I work better with academics in some cases as they look past the beauracracy, and are able to think critically and form opinions on evidence in many cases.

As I write a report on TEF submissions, it is increasingly clear what a complex set of roles and functions Universities have that may be captured, more or less, with the following terms and phrases, not placed in any particular order – educating, conducting research, recruitment – local, national, international, engaging with industry/society, knowledge transfer, developing employability/career skills, promoting and supporting entrepreneurship, disability support, managing collaborations/off shore campuses, ensuring effective delivery face-to-face and online, investing in technology (for delivery, for learning analytics, for students…), maintaining/expanding the infrastructure, student well-being and support, advising, gathering data for REF, TEF, Fair Access, NSS and on student satisfaction/learning gain/experiences/graduate jobs/value added and then making improvements where not ‘satisfactory’, marketing/branding, maintaining ethical behaviour and integrity (student work, research ethics), timetabling, getting and maintaining PSRB and educational accreditations, supporting student learning and study skills, international placements/study abroad, lobbying and networking, programme management and updating, quality assurance, updating skills via CPD offering, accrediting teachers, student engagement, bringing in research grants, research coordination, external examining, library services…….. I am sure I have left out many other roles and functions. Academics (I am one) like autonomy – for good reasons – it helps them think and produce good research, but it also means that we can miss what is going on around us in our very complex organisations. All of these functions require specialists and support staff. More functions? More requirements for reporting? More specialists needed – otherwise, academics would be much busier than they are!

What is the core mission of a university? I would argue it is ultimately about the search for truth, and this requires a certain amount of autonomy and freedom.

The identity crisis of modern universities stems from the postmodern rejection that such a mission is possible, since truth does not exist, and if it does, it is not discover-able.

Instead the search for truth is just a pretension and its participants are ultimately caught up in a game of power.

The only truth that does it exist is scientific truth – that 1 plus 1 equals 2 – but there is nothing more to be said about scientific truth other than the fact that it keeps the TV working and is a bloody good thing when not in the hands of the Nazis.

And this is where we are at. Like a person who doesn’t know who he is, the university sector lurches from one crisis to the next. One day he thinks, I will be a businessman. Another day he thinks, I will be a scientist. Once in a blue moon (and rarely under the Tories) he will be an aesthetic.

But Signor University, you are none of these things. You are a Seeker of Truth, and until you recognise that, you will never be happy.

We are delighted to read this article and strongly endorse the arguments made which echo those we explored in a recent research paper (Knight & Senior, 2017).

Professional services staff are not the enemy within contemporary academia. Critics not only fail to appreciate the impact on administrative requirements of external legal, financial and regulatory requirements (as your article highlights) but also the wide range of other drivers, including multiple demands and expectations from applicants, students and other stakeholders. In the face of an ever changing complex modern Higher Education sector, those colleagues who are sometimes labelled as ‘first for the chop’ have crucial roles to play and should in fact be considered at the vanguard of developing excellence.

As you’ve highlighted much literature and many commentaries on this topic focus on how these changes have created a tension or divide between academic and administrative staff and a perceived managerial model where administrative staff have somehow taken control from academics leading to an “us and them” culture (the “us” and “them” being different depending on which staff group you feel you belong to). We present a more positive view that the evolution of universities has produced and requires a genuine partnership between highly skilled and valued academic and administrative staff who combine their individual expertise to deliver the University’s operations but also – crucially with students as the third partner – creates a collective enhancement of the student experience.

We have modelled this partnership as a core team with members having shared and complimentary roles. If the team works well, this should have benefits for all. It has the advantage of ensuring that the student voice is heard throughout the delivery of the entire learning portfolio allowing institutions to demonstrate how they have met the emerging ‘students-as-partners’ narrative. Encouraging professional support staff to lead on key responsibilities which might have previously been considered solely the remit of academic staff both empowers and develops administrative colleagues whilst enabling academic colleagues to spend more time enhancing their respective research, teaching and scholarly activities.

Central to all activities within successful HE is the idea that effective learning is carried out within a relationship. As universities increase in size and complexity and further embrace a consumerist philosophy the boundaries of this relationship can start to blur (Senior et al, 2018). One way to ensure that effective relationships are maintained is work together in a very transparent fashion.

Carl Senior and Trevor Knight

Knight, T., & Senior, C. (2017). On the Very Model of a Modern Major Manager: The Importance of Academic Administrators in Support of the New Pedagogy. Front. Educ. 2:43. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00043 http://journal.frontiersin.org/Journal/10.3389/feduc.2017.00043/abstract

Senior, C., Fung, D., Howard, C., & Senior, R. (2018, June 1). Student satisfaction in the age of consumer driven higher education. http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AC3Q6

Another excellent article, Paul.

Regarding REF and TEF, I don’t remember the increasing complexity of these exercises being driven mainly (if at all) by university administrators. Conversely, I do recall quite a lot of very good academic staff in the Russell Group university for which I once worked being rather keen on having their undoubted research excellence recognised in this way, so long as they came out of it well, as they did. As usual, the truth is messy and complicated.

The fundamental problem, beyond all the detail, is simply that “the idea of a university” is increasingly contested territory.

Gerry Webber