At the start of the academic year, we heard a lot from universities regarding ways to support students during the cost of living crisis – often thanks to the campaigning efforts of student leaders.

We saw universities introduce food banks and food pantries, offer discounted meals at campus outlets, expand hardship funds and roll out some one-off payments to deal with rising living costs and help students make ends meet.

It would probably be unfair to say that cost of living has disappeared from many universities’ priority lists, but the “buzz” (for want of a better word) around the issue seems to have quietened down – with few universities to date publicly publishing their support packages for next year.

Perhaps it’s the warmer summer months meaning few are thinking about turning the heating on, or maybe it’s that many students are currently finishing up their studies and are too preoccupied with crossing the finish line to be pushing for additional support.

Whatever the reason, it does feel that someone needs to think about what happens next.

Danger ahead

Unfortunately, for many universities, the unit of resource will likely be stretched even thinner this year, with no hints of any changes on the horizon.

Many Finance Directors are likely concerned about the possibility of continuing current commitments for a few years yet. There is also a looming problem with external suppliers such as caterers, graduation gown firms, or, most pressingly, private housing providers who may be inclined to lift rent freeze promises over the coming years.

However, it remains the case that universities, and SUs, should and could plan to ween themselves off of generating profit from students spending money to avoid pain in the long term.

This will likely need some creative strategic planning that means being a little bit more innovative, rather than adopting what “that university across the road” does.

It should also mean tackling some of the harder questions and problems from our original “100 ideas” list – because the “low hanging fruit” has already been eaten.

Glorious food

Up until now, much of the focus nationally has been on the impact of rising energy costs. Although high energy prices are, sadly, not disappearing, they are set to lower slightly by this Autumn.

Many students living in purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA), or “halls”, have been somewhat shielded from this aspect of the crisis because of all-inclusive bills deals being included in capped rent prices.

This is not to say that energy costs have not been a significant problem for students – we have plenty of evidence of students living in cold, damp conditions that prove otherwise.

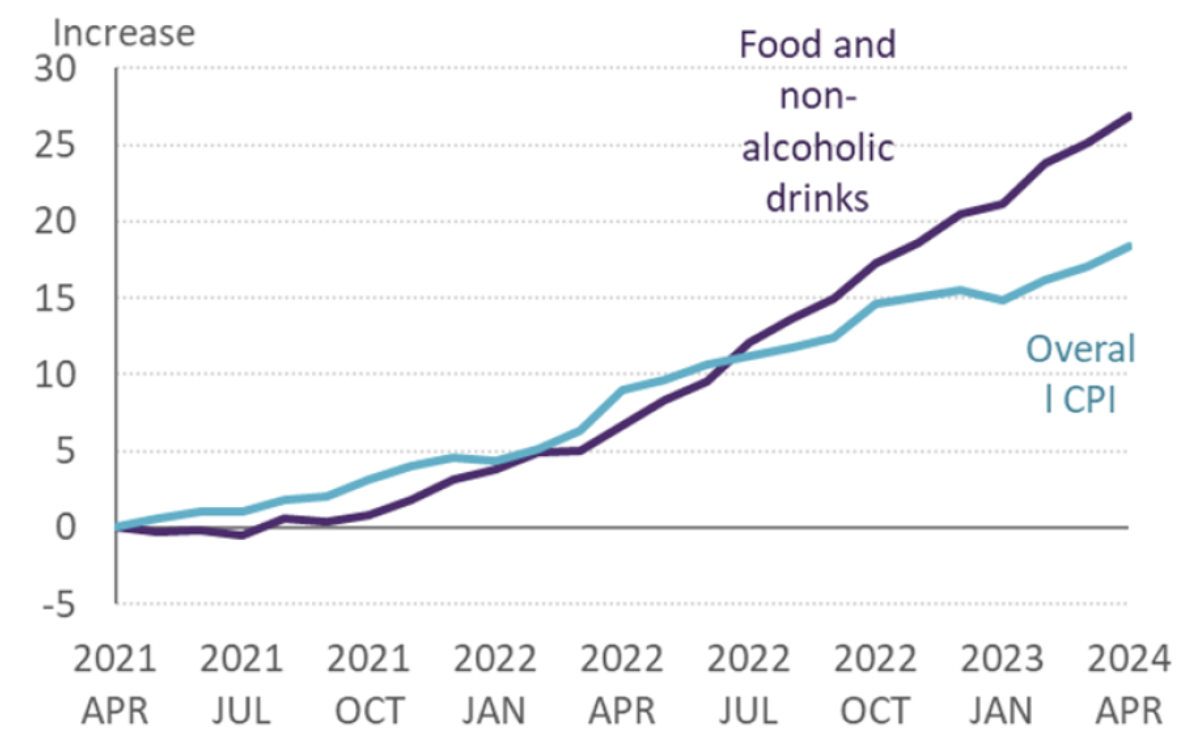

However, it seems a sensible guess that while the headline rate of inflation has fallen, this does not translate to lower prices overall. Likely it will do little to cushion the blow of rising food prices, which has not fallen at all and currently stands at nineteen per cent and could rise higher.

As research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation suggests, many households across the UK are struggling to afford basic items like food and clothing, which is mirrored in the student experience too.

Rising food costs will impact all students and, if your institution is debating which support measures to maintain over the next academic year, anything involving free, cheap or affordable food and essentials seems a sensible bet.

While it is difficult to prove the impact of these efforts, for instance have those free breakfasts made a difference in the number of students getting to the second year, but it feels fair to err on the side of caution with this one.

For SUs who have not developed an on-campus food pantry, or are experiencing resistance the idea advice and guidance can be found in this article. For those who already have one but want to improve things for the next academic year, research from the US suggests the four main barriers to using the on-campus food pantry were:

- Social stigma

- Insufficient information on pantry use policies

- Self-identity

- Inconvenient hours

Research suggests that for them to be a success, action plans must be put in place to address student needs and increase awareness of the facility. One particular area that has made food pantries successful is volunteers’ involvement which ensures they are creating a welcoming atmosphere.

Most important was getting messages “out there” that showed students they were not the only people experiencing food insecurity, and sharing these student stories were found to be just as important as getting the details of the service itself out there.

Students at work

Supporting students at work is not a new issue, but the extent to which it is impacting a growing number of students, particularly those from lower-income backgrounds or international students for whom living in the UK is proving much more expensive than expected.

There’s been a lot of noise from SUs and various sector bodies to raise awareness of how often students are working, and there is a separate conversation to be had about to what extent we can expect students to be fully immersed in campus activities when they have less and less time to spare.

A Sutton Trust article from earlier this year found that 27 per cent of students have taken up a job or increased hours to meet financial commitments, and our Belong research demonstrated that part-time work was one of the main reasons students did not attend lectures.

According to recent research from the University of Lincoln, there are a few things that institutions can do to better help working students, including training staff to be cognisant of the challenges student-workers face and how these may manifest in problematic student engagement behaviours like low attendance, stress, late submissions and these should be treated with concern and empathy, rather than punishment.

The summer is also the perfect time to reform timetabling to ensure classes are tactically timetabled, e.g. days clear of classes, classes less spread throughout the week as well as giving students access to timetables in sufficient time before the beginning of term so they can give current or future employers their availability.

I (don’t) know my rights!

Amongst the researchers’ recommendations is a suggestion around improving students’ knowledge of their working rights and establishing routes to equip them with skills to address issues, whether this be through info campaigns run by the SU or support from the Careers teams.

Generally speaking, the sector is well-versed and able in supporting students to be capable graduate workers, but what is less common and clearly needed is educating students on their rights as workers and giving them a space to turn if they feel those rights are not being met. This is particularly important for growing international student populations who are restricted on the number of hours they can work due to visa requirements.

Yet, anecdotally we know international students are often at greater risk of working in the “grey” economy or are more vulnerable to working in places with dubious workers’ rights provisions. These students often feel unable to raise these problems with their university for fear of an impact on their visa status.

SUs should work to break down barriers amongst international student communities when it comes to asking for support, as well as working with their institution to establish a space these students can come to receive support, both emotional and financial, to help them leave potentially harmful situations.

If you’re looking for inspiration, this checklist from Greenwich SU is a great place to start.

Student employment strategies

One of the initial ideas in our “100 ways to get the cost of living down for students” article was to employ more students on campus, and not just for the odd campus ambassador role on open days. This is a challenge for both SUs and universities.

For every job posting that goes up on campus, institutions should reflect on whether, on balance, that job could be done by a student, or a group of students on a part-time basis – even with a compromise on quality.

These jobs should go beyond that of campus coffee shops and bars – though they are a good place to start and consider professional service roles like administration, communications, and marketing opportunities.

This way students receive well-paid, good-quality jobs that provide them with employability skills to prepare them for the graduate market, as well as putting more money into students’ pockets.

In this vein, developing a fully fleshed-out student employment strategy feels long overdue. Part of this should be focused on getting more students involved in the running of institutional services, this strategy should also look at working collaboratively with local businesses and unions to promote good student employment practices.

Perhaps this could follow the framework of “good landlord” systems, creating a list of certified reputable local employers who adopt schemes such as Good Student Employer Charter and actively encourage student applicants.

Looking forward

Understandably, these solutions alone will not “solve” the cost of living crisis for students, there are a lot of external factors at play and it’s easy (and sensible) to feel that individual ideas will make little difference. However, it’s pretty irresponsible to presume that unless universities act, anyone else will do anything to make things easier for students.

The more SUs and their institutions work together to learn, pilot, and test new solutions to try and make things better for students – and be visibly seen to be doing so, the better off we all will be.