A running theme here on Wonkhe is the extent to which any issue that involves students (at least in England) is assumed to be the sole responsibility of the higher education bit of the Department for Education, or the Office for Students, or vice chancellors – and therefore any fix is to be funded through tuition fees.

Take the launch of the Home Office’s new strategy on tackling violence against women and girls, which comes in the slipstream of both the Sarah Everard case and a large volume of disclosures of harassment and assault in education on the Everyone’s Invited website.

Here’s the bit on higher education:

The Department for Education will work with the Office for Students to tackle sexual harassment and abuse in higher education settings, including within universities. We are absolutely clear that sexual harassment is in no way tolerable on campuses or in online environments and will continue to encourage higher education providers to review and update their systems, policies and procedures, in line with the Office for Students’ statement of expectations on harassment and sexual misconduct before the next academic year.

These steps also include exploring further options to ensure that all providers see the statement of expectations as the minimum standard for addressing sexual harassment on campus and how the Office for Students can take action against providers who are not doing enough to support students experiencing harassment. This will include the Office for Students considering options for connecting its statement of expectations to its conditions of registration. The Department for Education will also review options to limit the use of Non-Disclosure Agreements in cases of sexual harassment within higher education.

If that all sounds familiar – that is indeed because we’ve heard it all before. Unlike, for example, the detailed and substantial work that Ofsted has been busy with in schools, we have an unfunded strategy that appears to consist of OfS re-releasing a “statement of expectation” on higher education providers that has no basis in formal regulation, and both Michelle Donelan and Nicola Dandridge writing a letter to VCs.

In fact in many ways it’s even weaker than when then Business Secretary Sajid Javid wrote to then Universities UK boss Nicola Dandridge to call for action in 2015.

You can see what’s happened here – the civil servants in the Home Office have done the ring around and asked DfE what its plans are for inclusion in the masterplan, and so DfE has responded by saying what it said a few weeks ago. The problem is that like all wicked policy problems, this issue needs a proper, substantial, multi-layered and multi-agency plan to both understand it and tackle it.

Actually, to be fair, there is another bit on HE:

In addition, the Department for Education is exploring how university students might be utilised to support peer delivery of RSHE lessons in schools. A 2019 Universities UK report highlighted that there is significant value in building relationships with young people prior to entry into Higher Education, as it helps ensure continuity of messaging and cultivate active leadership in students from the outset. Some Higher Education providers already deliver sessions focusing on consent in schools, and we are exploring how these models may be further expanded.

No doubt lots of students will support that idea. But the brass neck cheek of a government doing pretty much nothing to tackle the issue in higher education, while expecting students to volunteer to deliver consent training in schools is really quite breathtaking.

These are the sounds of the wickedness

When I’m working with SUs on policy issues, one of my warnings to them is to not depend too much on a single solution that allows people to think that box is ticked. The delivery of project work can be satisfying but illusory – because without impact evaluation and a wider strategy, it’s often just well meaning pebbles in the ocean.

An example I often use is that of consent education. In the suite of behavioural change policy solutions that I discussed in our series on Wicked Problems last year, the “voluntary online sexual consent module” is your classic egalitarian solution to a deep and complex problem, which not only fails in context but also on its own terms – because anyone that’s ever collected the stats will tell you that hardly anyone takes part, and the characteristics of those that do are much more likely to be victims than perpetrators.

So it was interesting to see HEPI’s summary Sex and Relationships Among Students report back in April, which tested student attitudes towards to consent education. Both the Policy note and coverage surrounding it looked at whether the focus for it should be on pre-university, the induction period or on an ongoing basis – and also asked whether there should be a pass/fail test.

I tend to have a natural kneejerk reaction when it comes to findings of any sort that allow us to say “well that’s schools’ problem” or “well it’s an issue in wider society too” – because that can also be a way of letting the sector off the hook for the environment it has to create and nurture.

But on the other hand, I’m wary of putting too much “onto” universities where tuition fees end up paying for wider failings of the state, and where those who don’t go to university are left unprotected. And anyway – if there’s a problem in schools, that means children could be being harmed, and that means we should be concerned.

Put another way – if we believe in a “consent test”, shouldn’t it apply at Level 2 or Level 1? Why are we saying that people who wander off to university should understand consent as a minimum but we don’t care about anyone else?

So now it’s been released as HEPI publishes the fascinating full report and survey data, time for some interrogation into the full dataset. The widely reported stat was on students having to “pass an assessment to show that they fully understand sexual consent” before entering higher education. But the polling also included a question on whether students should have to pass such a test before even being allowed to apply – a different kind of minimum entry criteria, if you like – and there some 48 per cent agreed and 25 per cent disagreed.

Students very much appear to want this sorted at school or college.

Split difference

One of the intriguing things about that finding was the splits – because we know from other types of behaviour change work with students that blanket/universal/one size fits all approaches don’t really work. Health warning here – once we’re down to looking at differences between student type, we’re in the realms of problematic claims to real representativeness because of the low numbers involved. Nevertheless there’s a tale in HEPI’s data that at the very least deserves, as they say, further research – precisely because of the potential policy implications.

In other words, a dive into the splits suggests an important hypothesis for further testing that is very much about the sort of pre-university education that students at a given higher education provider experienced.

On that question of whether students should have to pass such a test before being allowed to apply, the average of 48 per cent falls to 38 per cent for men at state schools, and up to 57 per cent for men who went to a private school.

What that doesn’t tell us is whether that’s because men who were state schooled think such a test would be unnecessary or whether they’d fail it. Nor does it tell us whether those men that went to a private school think more of them need the education, or more would ace the test – so I dived in further to look at some of the other differences on school type and gender.

There’s a couple of questions in there on attitudes that raise all sorts of questions about what is happening in the private school system. Just 14 per cent of students agree that “stereotypes are harmless to others”, and 70 per cent disagree. But that changes to 26 per cent agree and 48 per cent disagree for those who went to a private school. And that changes even further to 36 per cent agree and 31 per cent disagree for privately schooled men. There’s a very interesting “culture wars” finding there that deserves interrogation.

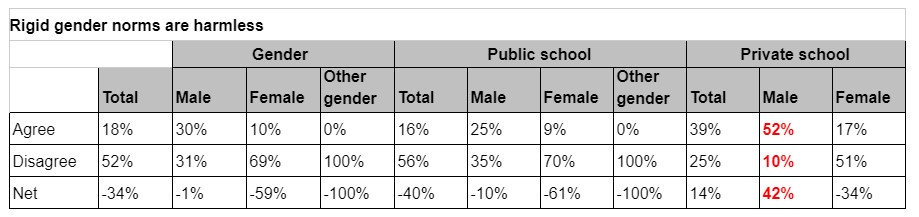

A similar question asking if respondents would agree that “rigid gender norms are harmless” generates similar results. There, 18 per cent of students generally agree and 52 per cent disagree. That’s partly about the gender of respondents (men runs at 31 per cent agree but women 10 per cent) and school (16 per cent agree state school, 39 per cent agree private school). Fuse that intersection and you get 9 per cent of state schooled women saying that rigid gender norms are harmless, and 52 per cent of privately schooled men (hereafter PSMs).

Confidence is a preference

Those numbers would be fascinating enough in the context of many of the culture wars “debates” in the press – but there are significant differences on other issues.

When students were asked to reflect on being able to “explain what constitutes sexual consent to a friend”, 44 per cent strongly agreed, but just 26 per cent of PSMs agreed. “Confidence in understanding what constitutes sexual harassment”? 40 per cent “very confident”, but just 33 per cent PSMs ticked that box. “How to communicate sexual consent clearly”? 47 per cent very confident, 34 per cent for PSMs. And “confidence over what constitutes sexual consent”? 59 per cent general, 37 per cent PSMs. There the differences between gender generally are negligible – it’s the school type that generates the big differences:

You get this far and you start to wonder if there’s a real problem emanating from our private school system, which then feeds the universities that disproportionately recruit from those schools, which are then disproportionately featured on Everyone’s Invited.

Peer pressure

The survey asked to what extent respondents would say they are confident in “how not to put pressure on others to have sex”. 61 per cent ticked very confident, falling to 41 per cent of private school males. And particularly strikingly – confidence on “sexual consent is just as important in and out of a relationship” runs at 72 per cent agree generally, but just 52 per cent for males from PSMs:

Some of the other findings also tell a story. “I have used apps to seek casual sex / hook-up sex” runs at 10 per cent generally, but 28 per cent for PSMs. “I have paid for sex with other people” is 2 per cent but 12 per cent on private school males. At university, “I have had sex under the influence of alcohol” is 65 per cent generally but 80 per cent for PSMs. “I use contraception to protect against unplanned conceptions / unwanted pregnancy” is 61 per cent generally but 42 per cent for PSMs. And “I or a partner (former or current) have experienced an unintended / unplanned / unwanted pregnancy while at university” is 3 per cent generally but 10 per cent for PSMs:

Is education the answer?

There really is a lot potentially going on here – yet it may not be the case that changes at school would fix it (notwithstanding heavy caveats on not just numbers but the repeated use of “school” to denote “pre-university” in the survey). When asked if the education they received at school prepared them for sex and relationships at university, 27 per cent agree generally, 43 per cent from private schools agree and 52 per cent of PSMs. That said, when asked whether university is “not the right place to teach young people about sex and relationships”, 19 per cent agree rising to 51 per cent of PSMs.

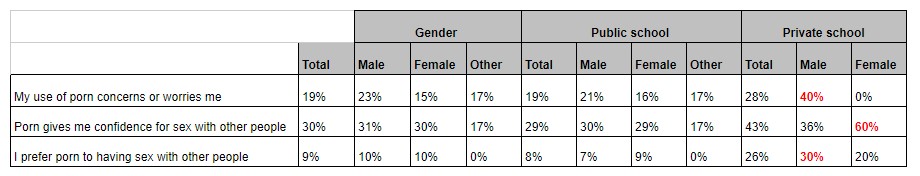

Is there something going on with pornography instead? Of those who’ve watched it, “My use of porn concerns or worries me” is 19 per cent agree generally, 23 per cent for men but 40 per cent agree for PSMs. And “My use of porn gives me confidence for sex with other people” shows up as 30 per cent generally for those who have watched it as a student and 43 per cent for PSMs. Preferring porn to actual sex in the porn user group has 30 per cent PSMs agree but just 9 per cent overall.

Without a larger sample that spans the whole of the education system, it’s difficult to draw clear conclusions from the data – not HEPI’s fault but definitely something that DfE and/or the Home Office ought to be thinking about if they were developing a serious system-wide response to everything from 2010’s Hidden Marks to 2021’s Everyone’s Invited.

It’s also important that we don’t demonise PSMs – but also crucial that we take the potential differences seriously too, particularly given there are differences in the way the state and private school sectors are regulated.

What’s clear is that students’ attitude to university-based consent education may be telling us much more about perceived failings in their own and others’ prior education than it tells us about university interventions per se.

And if this evidence was borne out in a bigger dataset, universities ought to be asking themselves “how many young men from private schools do we recruit” when assessing risks to their students – and making them pass a test on sex and relationships that covers much more than consent.

This tells us more about the surveyor than any of the students. The deadline implies that there are higher rates of rape among privately educated students – in fact the article is about how social science questions are answered which, being vaguely worded, have only a tenuous link to rape and sexual assault. e.g. being ‘not confident in explaining consent’ does not mean that they are against consent, or do not know what it is – in fact it may signal that they would like to discuss further – you just can’t tell from the question. ‘Rigid gender norms’ can… Read more »

If you had clicked through the link to the report you would have seen that the survey was conducted by a market research company, not ‘social scientists’.

I certainly wasn’t interpreting “not being confident in explaining consent” as being “against” consent, and I didn’t think Jim was implying that. I think “not confident in explaining it” is a finding in and of itself which doesn’t need to be treated as a proxy for something else.

I wonder if there’s a relationship between single-sex vs co-ed schooling behind some of this? Single-sex schools exist is public and private schooling, but I think there’s a higher proportion in the latter group.

The survey report analyses differences by student characteristics without giving a breakdown of the numbers involved – not a good practice for reporting data. This means we can’t draw meaningful conclusions from comparison across groups. You can’t tell if there were 300 male students from private schools, or 15. Different percentage rates across groups could easily just be an artefact of low sample sizes.

Martin asks a relevant question about single sex v co-ed, along the same lines what do the stats tell us about not-fully consensual sex/harassment against male students, by other students or staff of any gender? Yes that’s a huge can o worms to open, but that I’m aware of one that also needs dealing with.

So much to criticise here. I’ll just state one. The author repeatedly highlights general results Vs PSMs e.g. “shows up as 30 per cent generally for those who have watched [porn] as a student and 43 per cent for PSMs.”

The meaningful comparison to make is OBVIOUSLY between public school males and PSMs. Lumping females into one stat and not the other exaggerates the difference. Shoddy. One can only suspect bias. There IS interesting data here. You don’t have to play games to make your point