Welcome to the walk in degree

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

A “major misuse” of public money and potential fraud by students deal a “hammer blow” to the integrity of higher education in this country and “demand the firmest action.”

Just over a year ago now, The Sunday Times splashed on international students in feeder providers. This time around the online version of the reputation-damaging headline for the sector is:

Walk-in degrees, sham students and a giant university fraud scandal.

Franchising has finally hit the headlines – the “opaque corner” now has a spotlight on it – and Phillipson has announced that the Public Sector Fraud Authority, which sits under the Cabinet Office and the Treasury, will be given the job of investigating the suspected exploitation of the student loan system.

What that will add to the National Audit Office (NAO) report from last year, which itself mentions the Government Internal Audit Agency’s own investigation, is unclear. The Treasury certainly didn’t seem to think that was needed as recently as last autumn.

Regular Wonkhe readers won’t be learning much new here on the explosion in franchising, but there are some new nuggets – although quotes and leaks in the story tend to look like individuals (in what feels like a pretty broken system) trying to chivvy things along or covering backs.

The story lifts various numbers from the NAO’s largely ignored report into the issue in January 2024 – but evidently “recent investigations” revealed in documents seen by the paper, point to “far greater levels of potential fraud,” with estimates that it could run to “hundreds of millions of pounds.”

Applicants, the story says, are suspected of scamming taxpayers out of hundreds of millions of pounds for courses they don’t intend to take. It says that it has “discovered” that individuals with “absolutely no academic intent” are enrolling on degree courses every year to take out loans, with “no intention of paying it [them] back.” Officials fear there is “organised recruitment” of Romanian nationals in particular.

We learn that at some universities with franchised providers, “between 35 and 55 per cent of applicants last year were Romanian” – little surprise to anyone on the app where the algorithm has spotted you’re interested in such things.

We did of course already know that in 2022–23 and 2023–24, just over 65 per cent of students eligible and applying for SLC funding to study on subcontracted courses were from nationalities where English is not the first language (but they are resident in the UK and are not international students) – twice the proportion seen among applicants to courses delivered directly by a lead provider.

We learn that some students who enrol on franchised courses drop out after receiving “their first £4,000 maintenance loan” then enrol again the following year to claim the money again, “according to a university employee.” Maybe that provides an explanation for the charts that DK has been running for a few years now – here, here and here.

SLC, for example, have told us that the number of students in course year 1 who received the first instalment of their maintenance loan but no tuition fee loan was paid has looked like this for the past few years:

| Number of students in course year 1 who received instalment 1 of their maintenance loan but no tuition fee loan was paid. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Domicile | ||

| Academic Year starting | England | Wales |

| 2020/21 | 9,546 | 1,887 |

| 2021/22 | 11,636 | 2,062 |

| 2022/23 | 11,952 | 1,970 |

| 2023/24 | 10,582 | 1,944 |

Much of the published story focuses on Oxford Business College, which is said to be at the “centre” of current investigations – it was of course the focus of a New York Times investigation in the summer of 2023. The Sunday Times says that its partnerships with Ravensbourne, Buckinghamshire New University and the University of West London have been terminated or suspended – although the latter two are still listed as partners on its website. Ravensbourne suspended recruitment to OBC courses in 2023 and the partnership ended by mutual agreement in early 2024.

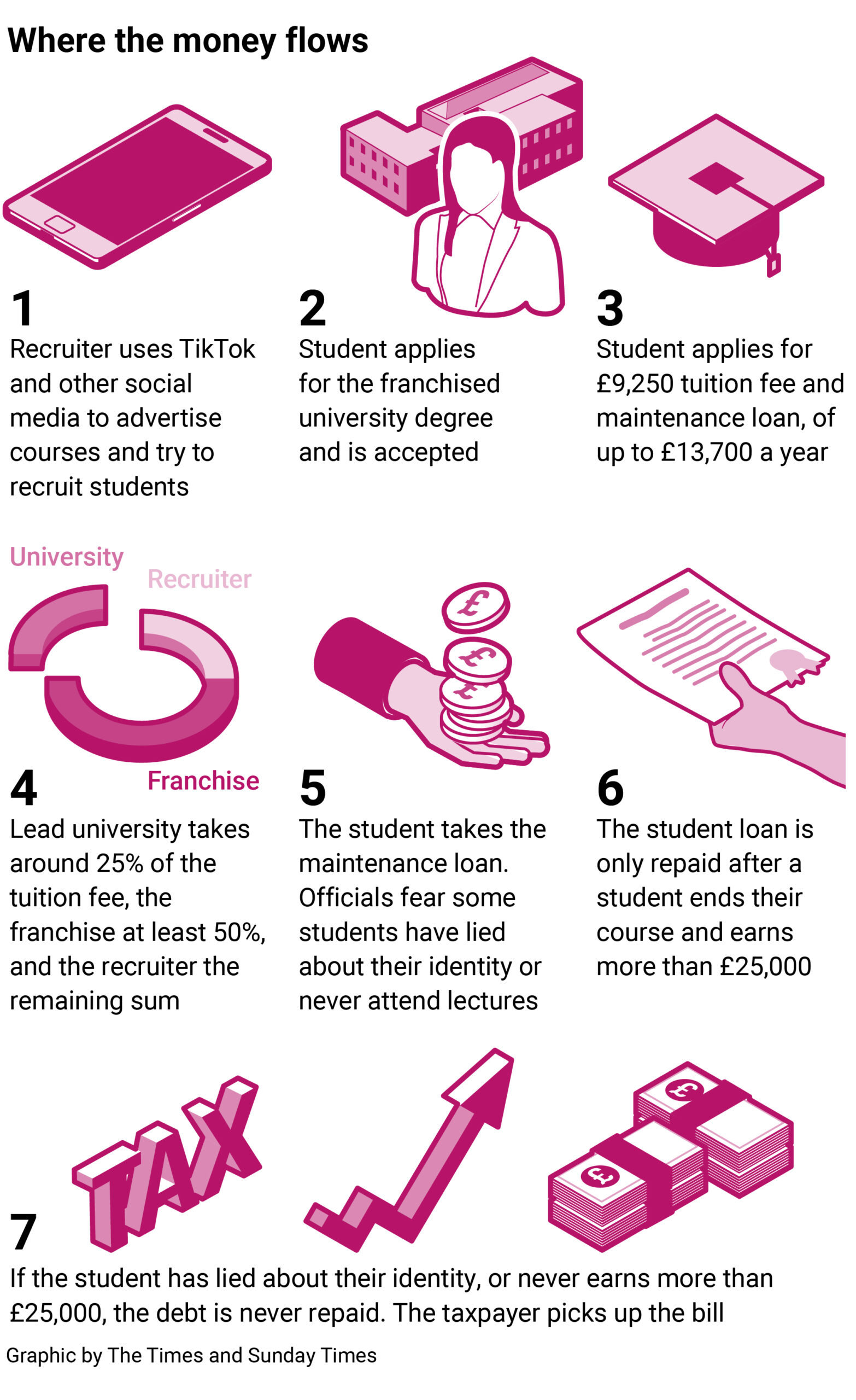

There’s also an amazing graphic describing “where the money goes” that somehow fails to inform readers of the profit made by the franchised-to providers once they get their cut.

I’m staring at one set of accounts right now with a £73m fees turnover, and a cost of sales (ie the actual education) of £17m. With another £17m on administrative expenses (likely the money paid to agents), that’s £31m profit after tax – and a 53 per cent profit pre-tax! Other examples are available.

In her accompanying op-ed, Phillipson says:

This problem has been growing and has been highly concentrated in a small number of providers in the sector. In the last academic year, five providers accounted for almost half of all funding applications from Romanian students. It points to targeted abuse of the system.

She reminds us that DfE is consulting on changes that would force all franchise providers to be regulated by OfS – steps that, even if they eventually go ahead, would stop a long way short of the clean-up carried out in FE in 2020. She also says that once the PSFA investigation is done, she will look at putting an end to the abuse of the system by agents recruiting students based in the UK, because:

…this government believes they should have no part to play in our system whatsoever.

Maybe she could use the evidence gathered from Robert Halfon’s “urgent investigation” into agents commissioned in January 2024 – which DfE perm sec Susan Acland-Hood and skills director Julia Kinniburgh said had been looking at domestic agents and recruitment in February 2024. All we’ve heard about that is that the Agent Quality Framework will be mandatory as of April – but that of course only really covers international recruitment and agents.

In the piece, OfS CEO Susan Lapworth is keen to remind the paper that “our powers in this area are limited.” What it can do is put its boots on the ground – but news on its round of investigations into franchised business courses with a foundation year is conspicuous by its absence (although this one, from a previous round of boots, was a doozy).

We could look at the outcomes performance of franchised-to providers – if it wasn’t for the fact that OfS has been refusing our FOI requests for months on the basis that “premature disclosure” of numbers that it already includes in franchised-from dashboards, DiscoverUni profiles and assessments of performance would “prejudice public affairs” and “misallocate staff resources.” That’s one way of looking at it.

To be fair, OfS has long argued that it lacks powers in this area, and Phillipson does promise that:

I will also bring forward new legislation at the first available opportunity to ensure the Office for Students has tough new powers to intervene quickly and robustly to protect public money, in addition to the stronger remit I have given it to monitor university finances.

Maybe that will address attendance. In the story, a senior source at OfS says:

The problem with attendance is proving it and what does attendance mean.

That’s an issue the PAC was exercised about, too – although the eventual response doesn’t scream “well that’ll fix it”.

Phillipson says that franchises can reach students who struggle to access higher education “because of where they live”, although London, Manchester, Birmingham – where much of this stuff is based – are hardly cities starved of HEIs. Meanwhile UUK CEO Vivienne Stern reminds of the “legitimate and important role” for franchise provision in meeting needs of students for whom the traditional model of higher education may be difficult, warning against “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

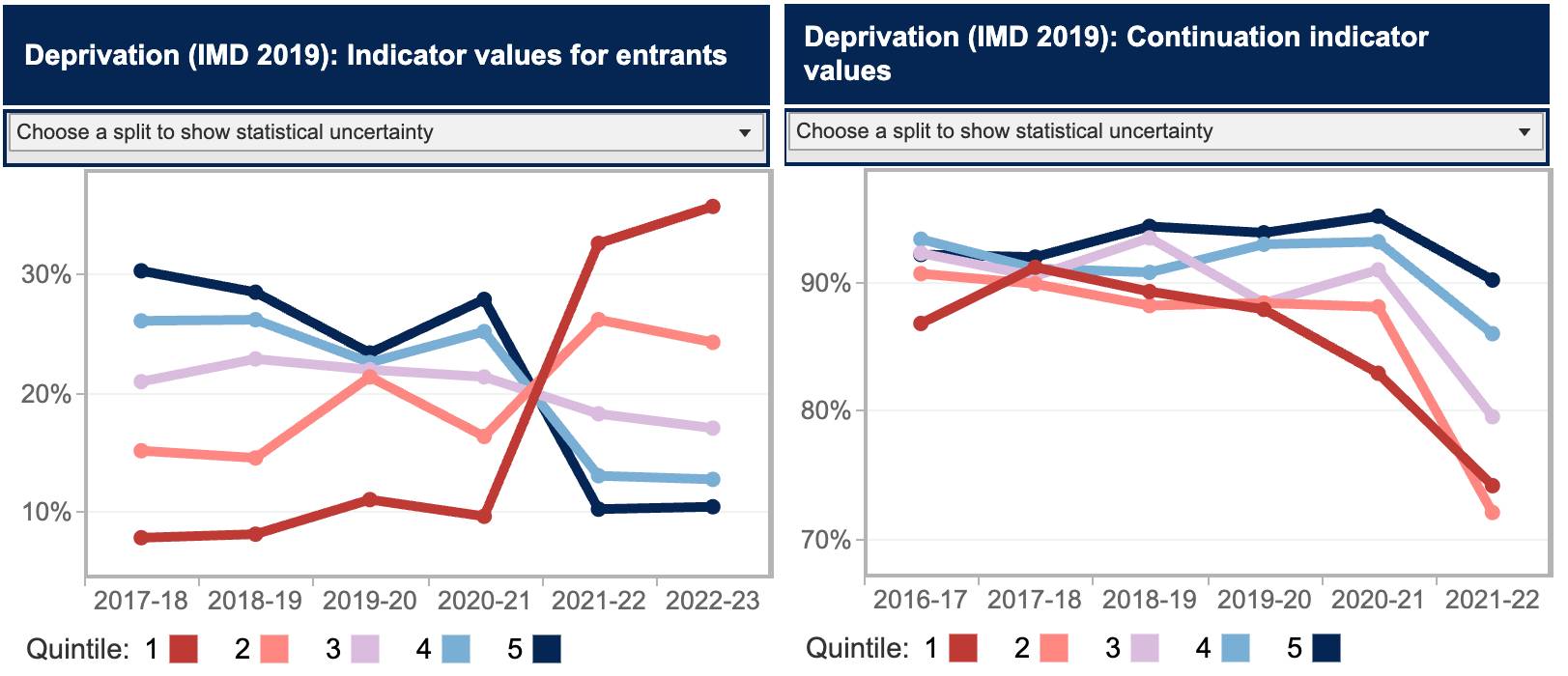

The sheer volume of bathwater, though, is pretty much the problem – and as for the baby, it’s still not clear that performance like this on “access” is as meaningful as many still say:

That’s a provider that has expanded its franchised provision in recent years (not that we get to see APP data split by subcontractual status), and HESES suggests it’s still getting bigger.

Giving poor communities access to HE is great – unless it’s milking communities already starved of social and educational capital by luring them into loans that the system subsidises. Access to HE works if the rich rub shoulders with the poor – both for the rich, and for the poor. It’s less convincing if the poor door isn’t even on the main building – but above a betting shop 100 miles away on the outskirts of London.

DfE says that where misuse or fraud is found, it has powers to claw back payments, and “won’t hesitate to use them” – and a “senior government source” says:

The institutions we are worried about, they used to have very small numbers, but they are now bloody enormous. We were totally unprepared.

Really? Even if we set aside the stuff we’ve been writing about for years, the Public Accounts Committee investigation, the National Audit Office’s work, the Mail story last September, Mike Ratcliffe’s work, the questions that still surround ABA’s closure and the almost certainly too little, too late nature of what’s about to be put in place as a response to all of that, readers with a longer memory might remember stories like that of the…

…Romanian builder, who cannot read or write, is being investigated for allegedly trafficking people up to 40 people to the UK to fraudulently sign up for £10,000 student loans before taking a cut.

College called “the ATM” by students who believe they can obtain loans of up to £11K a year and then not show up.

…much of which was highlighted in this Guardian investigation back in 2014. The accompanying video includes almost all of the same themes as those in the Sunday Times story. Phillipson’s op-ed says that it was the “decision of the last Conservative government, beginning in 2016, to widen franchise education.” Maybe that 2016 thing is a typo.

Those stories from the last decade led to David Willetts suspending loans to students from Bulgaria and Romania after an “unusual increase” in the number receiving support from the Student Loans Company (SLC). As many as three quarters of the students involved had failed to prove they were entitled to their loans, sources said at the time.

An NAO report and government promises of action to prevent a repeat, ensued – a decade ago. It really is this sort of thing that is causing the public to believe that nothing works and that nothing ever gets fixed. If today’s story is that this is one of the “biggest financial scandals in the history of our universities sector”, the problem is that 2014’s wasn’t another one – it was basically the same one, still going on.

As I’ve said before here, maybe regulation is the answer. But ministers have never announced that they’d like to see a collection of businesspeople appear out of nowhere, be able to rent some office space, run governance rings around well meaning (and desperate) universities to offer them their brand, deliver boilerplate business courses (often) badly, and employ salespeople to extol the virtues of the student loans system to those desperate for cash and a career:

Every pound spent tightening up regulation – every investigation, every ministerial op-ed, every insight brief, every boot on the ground, every minute spent in governing body meetings mitigating against the huge incentives for all the players – it’s all time and money that could be better spent on the sector’s other range of problems. The type of provision under the spotlight is solving a problem that is not just not necessary to have – at least not at system level.

Phillipson puts it like this:

Franchising in some institutions has become less about expanding access and more about meeting expanding overheads for hard-up universities. The system also lacks necessary guardrails against abuse.

The accompanying leader comment sticks the knife in more broadly, and argues that in a world that requires bespoke skills, simply sending teenagers away each year to study courses that, “even at our top institutions”, can be of questionable value appears “desperately out of date”:

Indeed for years the sector has grown like Topsy, with former colleges now rebranded universities, to the point where many degrees have become devalued. Universities ought to be among the crown jewels in the UK’s society and economy. Getting tough on abuses is a start. Asking what the country requires from its school-leavers is the real conversation we need to have.

It has a point – a Resolution foundation report at the end of 2023 basically said that while we need more graduates, we need to be much more careful about what they’re studying and where they’re studying it:

Those that simplistically paint a call for student number controls as freedom and expansion versus “the man in Whitehall will always get it wrong” probably need to accept that the world has moved on – and that it’s a lack of any attempt at planning or intervening in what students will study and where they’ll study that is contributing to our economic stagnation, and actually undermining calls for expansion.

On franchising specifically, it remains the case that reversing course will need careful handling to protect vulnerable students that have signed up in good faith, and require some assistance for those universities that are now relying on the funding. But while the specialist stuff looks fine, it also remains my view that Labour should do the only sensible thing – instead of fiddling with regulation, it should simply signal its intent now to stop funding the bathwater that is generalist, for-profit, franchised provision. It’s still not worth the risk.

This article was updated on 23 March to clarify that Ravensbourne had terminated its partnership with Oxford Business College.

There are currently 341 franchised private education providers operating in the UK, collectively enrolling hundreds of thousands of students. Major players include: GBS: 50,000 students Elizabeth Group: 25,000 students LSST Group, Fairfield, London School: over 10,000 students School Scholar System: 10,000 students Regent College (recently criticised heavily by OfS): over 8,000 students A newly established provider within the past 5 years: over 10,000 students Magna Carta: rapidly enrolled over 2,000 students in a single year, despite a Learning Delivery (LD) ban from a Nottingham-based university with over 6,000 students. Given these significant numbers, why does scrutiny and criticism seem selectively… Read more »

This seems to be an England problem created by the foolish deregulation and privatisation policies of the UK government. I see no evidence it is an issue in Scotland, no doubt because of the stronger institutional regulatory environment, the prioritised development of widening access through state regulated SQA qualifications delivered through the 26 community college system institutions rather than sub-contracting, and the more standard (by global comparisons) interface between school leaving and tertiary sector rather than the ‘gold standard’ over-specialised A levels designed for the elite top 10%. It’s not perfect here – funding is too much influenced by the… Read more »

… and the mess at Dundee University is completely the fault of England as well…. Because Scotland has such a strong institutional regulatory environment.

This article was updated on 23 March to clarify that ravensbourne had terminated its partnership. have you specifically written this article to support ravensbourne? Is there any particular reason or affiliation behind highlighting ravensbourne? moreover, where is your independent investigation?

It’s hard for even sector experts to believe the scale of this issue, as seen in the well-informed comments on this piece last year claiming there is no issue with Romanian students on franchised foundation years https://wonkhe.com/wonk-corner/the-public-accounts-committee-discuss-franchising/

Though it is incredible that the Secretary of State for Education claims to have been unaware of the data on nationality until The Sunday Times presented her with it last week – what are her officials doing?

It’s clear that Alternative Providers are being used as a convenient scapegoat for a broken system — and for the failings of traditional universities. This Wonkhe article, like others in the press, paints an alarmist picture of higher education franchising — one that conveniently overlooks the widespread shortcomings of the traditional university system across multiple metrics, while casting Alternative Providers (APs) as the villains of a crisis they didn’t create. Let’s be clear: where there is fraud, it must be addressed decisively and transparently. Bad actors exist in every sector. But to conflate all APs with a handful of poorly… Read more »

I have noticed an increase in people where their first language isn’t English applying and trying to get onto our courses, business courses in particular. 2 years ago there was a large group that turned up wanting to be interviewed and apply but they were all directed to do an ESOL course instead. Not surprisingly, none of them enrolled onto the ESOL programme which could have gained them entry to one of our degree programmes the next year. They clearly had no interest in gaining an education.

For details of the mid-90s franchising scandals see Farrington & Palfreyman on ‘The Law of Higher Education’ (2021, third edition) – pages 687/688, incl the f/n reference to the NAO Report. As in financial services and the periodic booms/busts, memories are short and lessons never learned or soon forgotten.