If we think about all of the Pathe newsreels that we’ve seen that feature students, two things spring to mind.

The first is an image of students as a kind of homogenous social elite – othered away into universities to be trained in how to run government and industry. The second is the image of student fundraising – the annual RAG parade weaving its way through the city, combining student high jinks with giving something back to the area.

Sadly, the contemporary framing of the contribution of students to their community this past year has been more about an unfounded assumption that they “caused” the winter lockdown – when the data tells us that their real civic contribution has been to stick to the rules to protect the vulnerable at the expense of their own education, experience and mental health.

Does this matter? Almost certainly. “Place” is increasingly important in a way that spans left and right, academic and vocational and the whole of the higher education sector. So over the next two years Wonkhe SUs and the UPP Foundation are working on a partnership programme to consider the role that extra-curricular involvement plays in the sector – in the education and development experienced by students, in the sector’s standing and reputation, and in the contribution it makes to places – campuses, local communities and the country.

As part of that work as we emerge out of lockdown, we recently held a round table to consider the issues at stake and the way in which the sector might work to address and strengthen these aspects of student community and citizenship.

Civic students

The idea that students can and should be a part of, and make a contribution to, the place where their university is is one that predates students’ unions and civic university agreements. If you’ve never seen it, we can’t recommend enough Georgina Brewis’ Social History of Student Volunteering.

In it she sets in an international and comparative context a one-hundred year history of student voluntarism and social action at UK colleges and universities, including such causes as relief for victims of fascism in the 1930s and international development in the 1960s.

What is interesting about that history is the underpinning realities of community for students:

- The university itself offered what Ross Gittell and Avis Vidal called bonding social capital – finding others like you – and creating powerful social networks between homogeneous groups of people, where occasionally Charlie Bucket would win to a golden ticket to its social mobility and career benefits.

- And interaction with the community through charity work or more radical types of community action would offer bridging social capital – interaction with people not like you – where value is created through networks between socially heterogeneous groups.

The above may well still resemble the reality for some students at some universities in some cities. But we know that the relationship between students and places has changed, with major impacts on housing and local economies. Far more students are “of” the local community to begin with. And we know that in and of themselves, campuses and their student bodies are less homogeneous.

Yet throughout the waves of expansion of higher education in the 80s, 90s and 00s that have generated these changes, we’ve paid little attention to the student community, students communities and their relationship to the wider community. And a model focussed on a “professional elite” of undergraduates training to be leaders has become complemented, or in some cases supplanted, by one of individual (and individualist) skills acquisition – positioning students as agents for the creation of wealth.

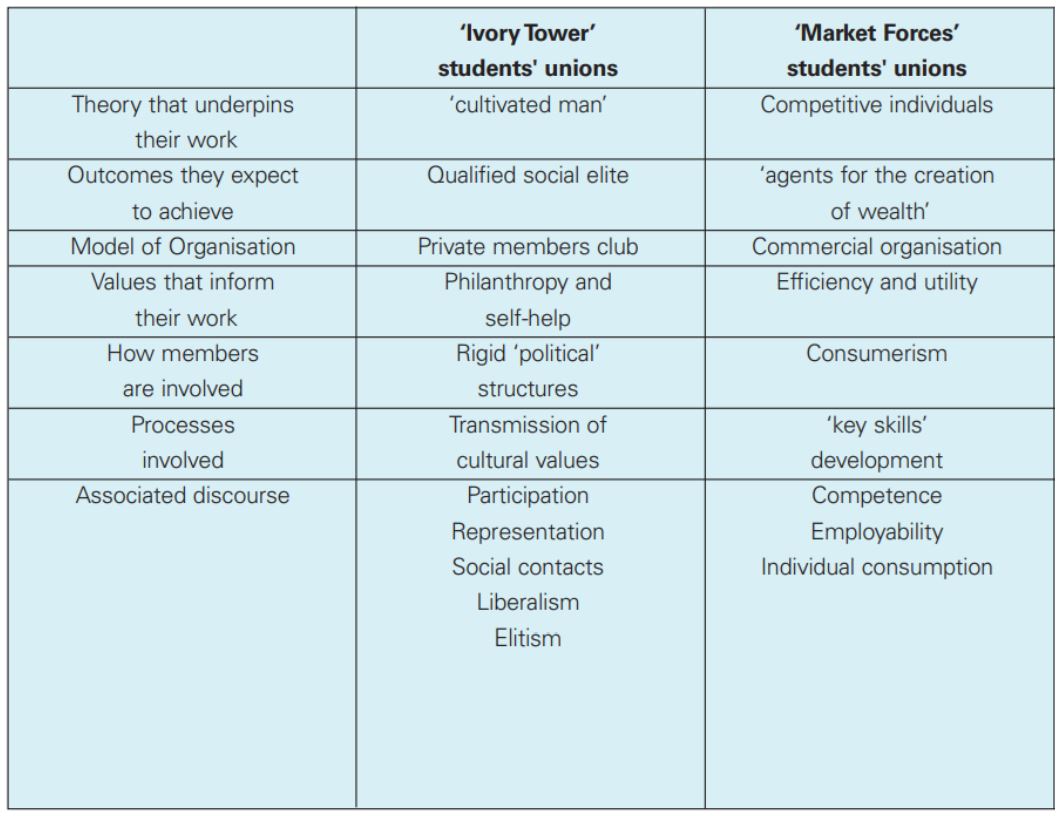

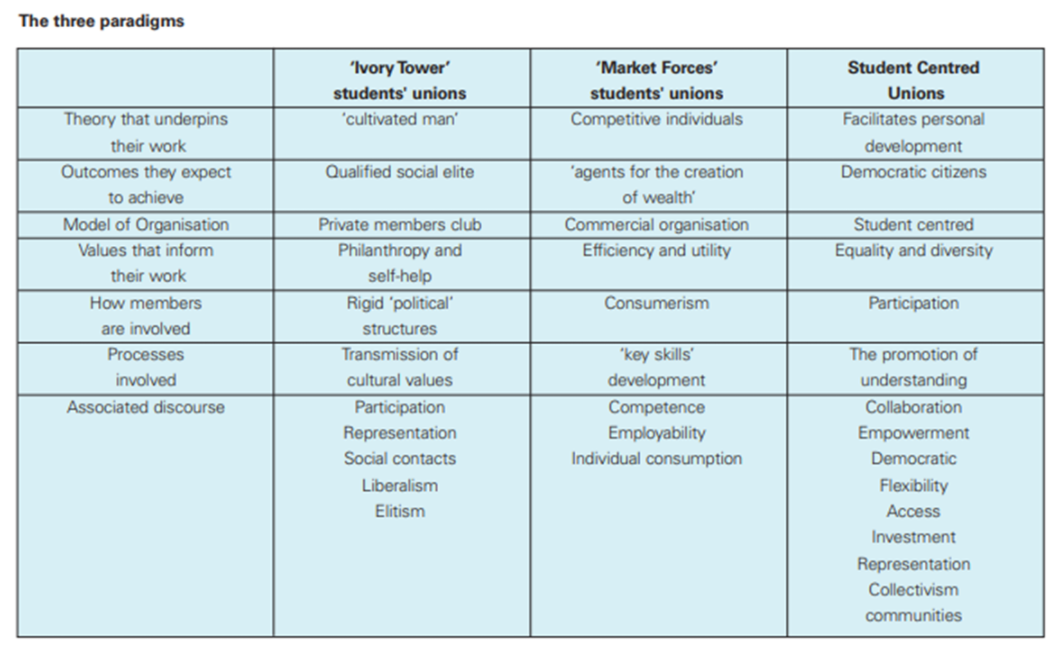

So when we met for the round table, we were keen to interrogate whether these models – of a “cultivated man” in a social elite or the atomised student engaging in skills acquisition – helped to explain the purpose and value of “getting involved” at university. And our participants were not so sure.

What are SUs for?

Despite what some politicians would have us believe, students’ unions were never originally really about politics and campaigning, left-wing or otherwise. They emerged, particularly in England, as ways to bring together student clubs and societies to share on administration and organisation costs.

Involvement in SUs and those clubs always did have educational and social capital benefits. But as the then Conservative government developed its vision for an expanded higher education system in the late 80s, some of the “elite values” that university in general and involvement in its activities specifically began to take on a new purpose.

Initiatives like “Enterprise in Higher Education” stressed the need for the university experience to imbue and generate (key, transferable) skills of use to employers in the market, both through and around the edges of the curriculum. By 1995, Jim’s first NUS event as a middle-ranking SU rep at UWE was not one discussing loans or grants, but one held at the Ford Motor Company HQ – sponsors of the “National Student Learning Programme”, a key skills training initiative part-funded by government designed to make sure that course reps and sports captains could “speak in public” or “communicate with confidence”.

Today, few graduates will pass up the opportunity to discuss the skills they have learned in such activities on CVs and in Job Applications. “Graduate attribute frameworks” and the ilk will stress the acquisition of skills from leading a team or organising an event. And organisations like the Sutton Trust worry so much about the contribution that those activities make to getting a good graduate job that they research the impact on social mobility if some students missed out on them during the pandemic.

But maybe there’s more to all of this than a choice simply between the creation of an exclusive “professional elite” with some benevolent community work, and the atomised individualist graduate with a CV full of skills to sell to whichever employer will listen.

Getting political

The Conservatives these days tend to be quite down on students – characterising those with a conscience as social justice warriors or snowflakes trained in their wokery by the left-wing madrassas that are students’ unions. But it wasn’t always that way.

In October 2007, the then shadow minister for higher education David Willetts delivered the inaugural lecture to the Sheffield University Public Service Academy – and surprised many an onlooker by proffering a different view of students and their unions that was focussed on community:

The student is not just a free-floating consumer. He is a member of a community. To this end, we should strive to foster the idea of the university community. Each and every university is its own community – its own society. Whether it be a leafy out-of-town campus, or spread across the centre of London, every university, and every student body, has its own collective feel, challenges, successes, character. But the hub of these university communities is not the university itself. It is not the Vice Chancellor, the central administration or the quadrangle. It is the students’ union.

Students’ unions are playing their part in their local communities: Charitable fundraising; university governance; sports and fitness training; examination guidance; job centres; equality campaigning. I could go on. The Party has recently rediscovered its commitment to social responsibility – or what I have called ‘Civic Conservatism’. It is an interest in institutions which help build a strong society. To local schools, hospitals, charities, friendly societies, I would add student unions.

We value student unions. We salute them and what they achieve for and on behalf of students. Without them, universities would be much poorer institutions, as would the employers, causes and political parties who take on their alumni.

Willetts’ brand of civic conservatism built upon long traditions of valuing community in the party, and led to moments that included 18th Century philosopher Edmund Burke being described as the “hottest thinker of 2010”:

To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country and to mankind”.

His argument was that we can only experience the world through the people and location around which we grow up. Necessarily we form attachments to people and places, and a connection to a locality implies a connection to the wider whole – hence the “procession towards a love to our country” which follows from love for one’s local community.

Those ideas of civic conservatism eventually ended up mangled into David Cameron’s “Big Society”, and never really escaped a critique surrounding disinvesting in the state and palming problems off on communities to fix.

Today, a Conservative party generally seen as a party that expanded university places in the last decade – the so called graduate “anywheres” – now turn their attention to the forgotten “somewheres”. What used to be left to “markets” is now under scrutiny – with initiatives like Danny Kruger’s new social covenant reinventing Burke again, proclaiming that “we are most happy and most safe when we live and work in association with others”.

These movements should intuitively understand the value of students’ unions, student societies and student volunteers because of the way in which they build communities and community on and off campus. But because of the negative narratives of activism and “woke snowflakes”, even communitarian elements on the right tend to be sceptical of all things university – except when it comes to their children or relatives.

And Labour might disagree (for now) on fees, but it is not necessarily convinced by the expansion of the sector either – and it too wants to steer tertiary towards a more vocational/level 4/5 future – one with “place” and “community” at its heart.

So politically, there is a threat and an opportunity here. Hiding students away from local MPs while senior managers don hard hats and VR visors for their visit around the labs isn’t going to work in any political climate, let alone now. Understanding and promoting the contribution that students can and do make to their own and others’ communities could be crucial.

Social capital in higher education

As we suggest above, despite the positioning of students as “anywheres” and those that don’t go to university as “somewheres”, much of the theory should make sense to us in higher education. Think back to last October. Support for students comes both “horizontally” (friends, family, course mates, societies) and “vertically” (academics, support services etc).

A big problem this year has been that the social capital capacity of the former just didn’t develop in anything like the same way this year as in normal years. So to compensate we had to massively step up the “vertical”. It reminded us that as much as students need good teaching and support services, they need each other – for their health, their educational outcomes, their social activities and their development.

So when we apply social capital theory to the student experience, it’s possible to become both concerned and intrigued by the possibilities.

Our participants at the round table asked interesting questions:

- What might be done to help students who will struggle to find others and benefit from “bonding” social capital – especially on the way out of the pandemic?

- Once there, do we leave students in disadvantaged pockets providing “bonding” support for each other – or do we cause the more socially exclusive groups to interact and open up?

- How much active work goes on interrogating NSS Q21 (“I feel part of a community of students and staff”) at institutional, programme and student characteristic level?

- Do we think about how much bonding and bridging is going on – and who is and isn’t benefiting and why? Are there measures? Do we have good – or indeed any – data?

- How much of what Robert Putnam calls “linking” social capital happens – where students are connected with external institutions that can enhance their capacity to gain access to resources, ideas and information from formal institutions beyond their community?

- Should we accept the informal “social sorting” that clubs and societies do on campus and “bridge” the groups, or work to make those groups more diverse to begin with?

There were ideas for action too. One group suggested that commuter students should be both supported as a group but also enabled and funded to lead projects that involve other campus groups in local community projects. Another said we should train students to become community organisers and take some responsibility for addressing issues in their local area.

Another suggested a kind of “civic skills” model – stressing the value, importance and opportunities to develop skills that will eventually see those graduates go on not to just create wealth, but create a better society and a better world. Another said that SUs need help to employ not just administrators and marketers, but community development professionals who can use the smarts on their degree to build diverse communities both on and off-campus.

Another said that we should develop meaningful measures of “bridging” social capital. Instead of working out if the “disadvantaged” can “join the club”, why aren’t clubs and courses and whole institutions measured on how many opportunities there will be to interact and bridge with those “not like me” in general?

Another argued that students’ unions and their university PR and press people don’t do nearly enough to surface some visibility on their work in this area with politicians across the political spectrum. Showing off the latest kit is one thing – showing the contribution students can and should make to society is quite another.

Some wanted government to help stimulate partnership work with communities and universities to help their local communities recover from the pandemic. Others wanted more alignment and engagement with the curriculum. Some wanted to see student accommodation at the centre of these strategies as town and city centres transform in coming years.

One contributor wondered why it was that their university had a strategy for improving the reputation and image of their university locally, but not their students. Another noted that their societies tended to be wheeled out on open days but shielded from the local community.

What all of the groups agreed on is that as we emerge from the pandemic, students are desperate to re-bond, re-bridge and re-link, both for their own mental health and to meet the egalitarian goals that Gen Z has for their education.

Leaving that to chance will mean more of the same – “cultivated man” and some transferable skills for the club captains. Investing now in time, coordination, social norming and models of what we mean by the “civic student” could transform both the post-pandemic student experience, and the world around students as they graduate into it.

For a critique of the idea of the civic university see my paper published in Civic Sociology, September , 2020 – https://online.ucpress.edu/cs/article/1/1/14518/112927/Civic-University-or-University-of-the-Earth-A-Call-for-Intellectual-Insurgency