If you still imagined that the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) would mean that a student studying any module from any course would be eligible for 30 credits of funding, it’s long past time to disabuse yourself of that notion.

Under the latest plans, eligibility only extends to short courses dealing with those subjects identified as national priorities – via a somewhat tenuous link to the industrial strategy – along with HTQ modules. Everything else in higher education will be funded by year of study, as is currently the case.

If you were thinking that this latest round of changes – taking us even further away from the initial dreams of Boris Johnson (or even Philip Augar) – completes the long gestation of the LLE in full detail you will be disappointed. For instance, the credit transfer nettle has yet to be grasped – with a consultation due in early 2026, not far in advance of the September 2026 soft launch. And there are, as we shall see, a number of other issues still dangling.

It’s a continuation of DfE’s gradual retreat from a universal system of funding that was supposed to transform the higher education landscape. No variable intensity, a vast reduction in modular availability – it just allows some of the short courses that universities and colleges already offer to be funded via the loan system (a measure, lest we forget, of dubious attractiveness to learners).

A bridge to nowhere

The Lifelong Learning Entitlement (originally known as the Lifelong Loan Entitlement) was announced by Prime Minister Boris Johnson on 29 September 2020, as a part of the government’s lifetime skills guarantee:

we’ll expand and transform the funding system so it’s as easy to get a loan for a higher technical course as for a university degree, and we’ll enable FE colleges to access funding on the same terms as our most famous universities; and we’ll give everyone a flexible lifelong loan entitlement to four years of post-18 education – so adults will be able to retrain with high level technical courses, instead of being trapped in unemployment.

Like most of Boris’ wheezes it was originally somebody else’s idea – in this case Philip Augar. He had a few more specifics:

The government should introduce a single lifelong learning loan allowance for tuition loans at Levels 4, 5 and 6, available for adults aged 18 or over, without a publicly funded degree. This should be set, as it is now, as a financial amount equivalent to four years’ fulltime undergraduate degree funding. Learners should be able to access student finance for tuition fee and maintenance support for modules of credit-based Level 4, 5 and 6 qualifications. ELQ rules should be scrapped for those taking out loans for Levels 4, 5 and 6.

But it makes more sense to think of the idea as being 100 per cent Boris in that it was a massive infrastructure initiative that he had no clue how to actually deliver (in all honesty, not much of Augar was deliverable either – perhaps that was the attraction). As has proved to be the case.

As you were

Let’s start by looking at what’s unchanged, following the latest revisions. The timeline for getting started remains as was: applications from September 2026 for courses and modules starting in January 2027. This still feels extremely optimistic. Plus – as has been the case for a while – a staggered rollout of standalone modules is planned, rather than an enormous platter of bitesize options spread out to pick from come next September.

The use of the current plan 5 student loan model, with its 40-year term and nine per cent repayment rate above what is currently around minimum wage, is still there – with all the peculiarities this will inevitably engender. If anyone was expecting a large scale shake-up of the student finance system any time soon, this should serve as an enormous hint that no radically new model is arriving in the short to medium term.

Also retained from DfE’s planning under the Conservatives is the system of “residual eligibility”, meaning how much loan is available to those who have already, for example, studied one undergraduate degree. You still get the equivalent of four years overall, though with lots of wrinkles.

The aspiration for each member of the public to have an LLE personal account continues – this will still include, in theory, information on one’s loan balances, an application tracker, and advice and guidance on career planning.

And in broad strokes the government’s rationale for the LLE persists: more flexible routes through tertiary education, support for upskilling and retraining throughout one’s career, and the promise of more learner mobility between institutions.

Picking winners

The LLE is replacing England’s entire student funding system, and so funding for full years of study at levels 4 to 6 – such as degrees or higher technical qualifications – will flow through it. In many cases, though, this is just a shift on paper.

What’s always been the more significant change is how it will bring the funding of individual modules into scope, along with the resulting interplay between single modular courses and larger programmes of study in a learner’s lifelong journey.

Modular provision that would be eligible had previously been defined as “modules of technical courses of clear value to employers” – this is now rejigged to:

modules of higher technical qualifications, and level 4, 5 and 6 modules from full level 6 qualifications, in subject groups that address priority skills gaps and align with the government’s industrial strategy.

We flagged this link between the LLE and the industrial strategy priority areas when the latter was published last month – and the updated LLE policy paper does say that DfE has worked with Skills England to assess skills priorities, though there is no detail on this.

What we very much don’t get is a mapping between LLE subjects and the industrial strategy sectors (the IS-8), or the priority sub-sectors and their corresponding links to certain regions or clusters which is, y’know, what the industrial strategy is all about. Arguably the main bone thrown to the industrial strategy is the concept of the government “picking winners” – but note there is no stumping up of public funds to support this.

So we get a list of which subject groups will be in scope for modular study:

- computing

- engineering

- architecture, building and planning, excluding the landscape gardening subgroup

- physics and astronomy

- mathematical sciences

- nursing and midwifery

- allied health

- chemistry

- economics

- health and social care.

Common Academic Hierarchy (CAH) fans will be delighted to spot that this appears to have been done (with the curious landscape gardening exception) at the very top level. These are very broad subject groups, which will contain multiple subjects with questionable relevance to the industrial strategy.

While on the face of it there is some ambiguity about whether this subject list refers to only level 6 qualifications, or to these and higher technical qualifications (HTQs), the accompanying provider preparation guide makes clear that the subject groups here are for level 6 qualifications only – and provision via HTQ modules covers many other subject areas, which in some cases overlap. This currently includes subjects such as business and administration, education and early years, legal and accounting, and many others – but these will need to go through the HTQ approval route.

The provider preparation guide suggests that institutions should be looking at their current degree provision, working out where it aligns to the priority skills gaps areas that DfE has identified, and then proceeding from there in thinking about what could be modularised. All modular study, remember, needs to form part of an existing designated full course which the provider delivers – we’re a long way from some of the previous visions of universities coming up with new stand-alone bitesize offers.

All the other funding eligibility rules for modular provision remain – they must have a single qualification level at level 4, 5 or 6, they must be at least 30 credits (though bundling up modules to meet that minimum is allowed), and a standardised transcript of some form to be determined must be delivered upon completion, to facilitate credit transfer.

But there is one change to eligibility rules – modular provision must not be delivered through franchised arrangements. This had always sounded like a recipe for disaster. The government has been gradually setting its face against a lot of existing franchising activity, given concerns about quality and reports of fraud.

Getting approved

The previous plan for approving modules (outside of HTQs) for LLE eligibility was what was being labelled a “qualifications gateway”, which the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education consulted on last January. This terminology has been scrubbed entirely out of the policy paper now, with just a note that “we will set out details on how level 4 to 6 Ofqual regulated qualifications could enter the market and access LLE funding.”

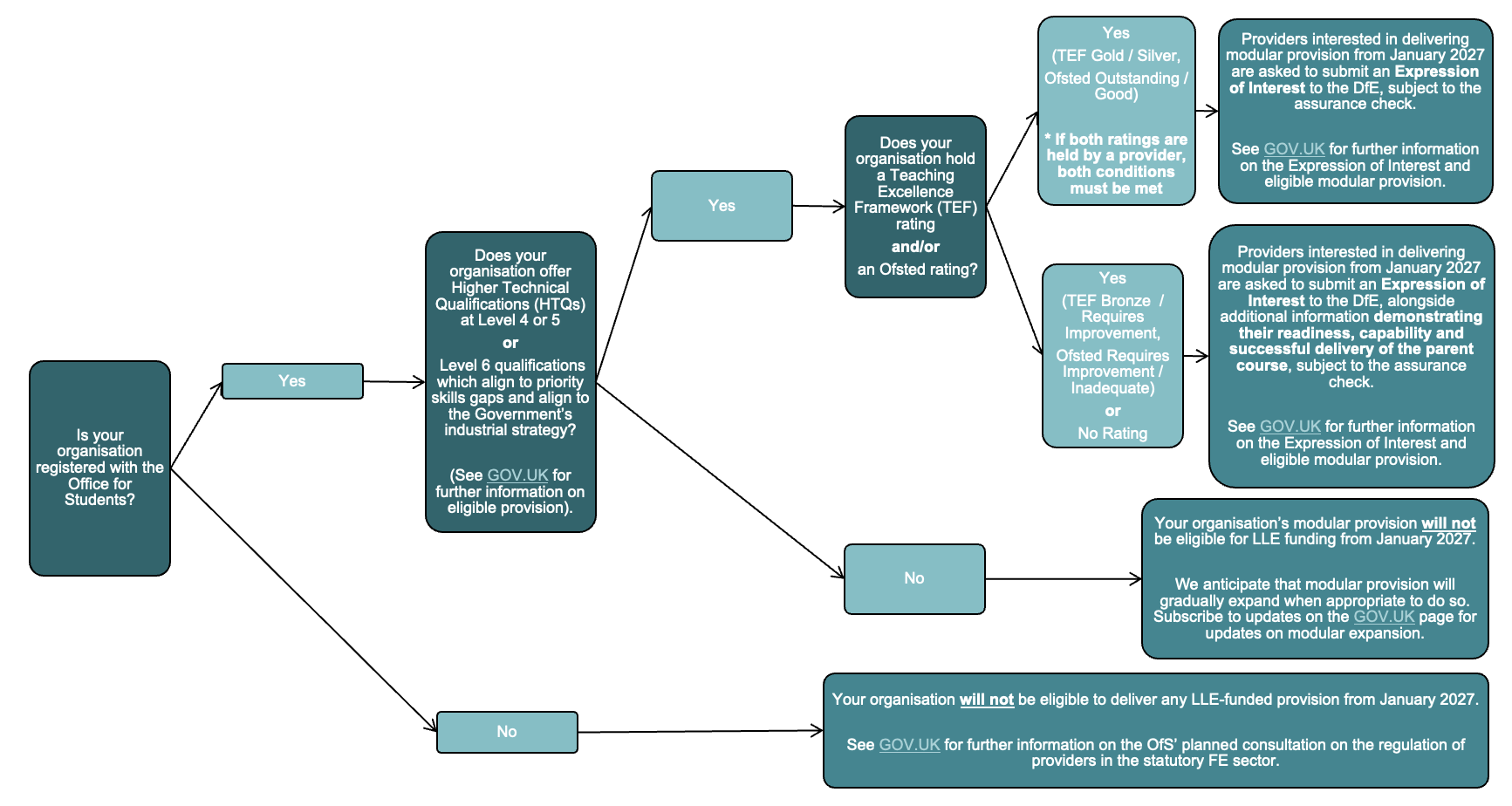

But there’s a new approval process in town – providers who are interested in delivering modular provision from January 2027 will need to submit an expression of interest, from this month.

This process will involve an “assurance check” – seemingly run centrally by DfE, rather than Skills England as might have previously been expected. There’s a wonderful flowchart in the provider guide, which you may or may not be able to read depending on how enormous your screen is:

That’s right – TEF! Providers with gold or silver will have access to a “simpler and quicker approval process” for modular provision. Those who do not will be asked to provide additional information around “readiness, capability and successful delivery of the parent course.”

Hang on, you cry, doesn’t the fact a provider is registered with the Office for Students demonstrate that it has “readiness” and “capability” to deliver courses of any type? Well, yes, it does. It is possible that DfE simply doesn’t trust OfS to make this kind of judgement – which would point to a rather larger issue with higher education regulation – or it could be that this is a last gasp attempt to give TEF awards some regulatory relevance.

This is also the case for those rated “good” or “outstanding” for Ofsted provision – and if Ofsted inspects your skills provision and you have a TEF award, they both need to make the grade. Now headline Ofsted assessments were supposed to disappear from September 2025, which makes this all a bit confusing.

If you don’t deliver HTQs or appropriate level 6 qualifications, it’s noted that modular provision is anticipated to “gradually expand when appropriate to do so” and so you may, one day, come in line for eligibility.

Regulatory issues

One of the areas the previous version of the policy paper promised was further information on the regulation of modular funding. This, rather oddly, is no longer listed under “next steps”, given that the update we do get is relatively slim.

What we might have expected was a follow-up to the Office for Students’ call for evidence on positive outcomes for students studying on a modular basis – a call for evidence which closed in November 2023, and we’ve heard little of since. As DK set out at the time, the quasi-consultation asked how things like the B3 conditions could apply to individual modules, and the regulator’s initial thinking seemed to be that completion would still be a valuable metric for regulation, as would progression – though exactly how progression was assessed would need to be refined.

There’s still no news on this complicated issue. The new section of regulation focuses more on registration categories, while noting that DfE “will refine the existing regulatory framework to ensure it is proportionate, is targeted [and] supports a high quality, flexible system.” If you were thinking that a whole new approach to learning would need a new oversight framework, the direction of travel suggests not.

The bigger regulatory news is that, likely to the surprise of few, the idea of having a third registration category for smaller providers offering level 4 and 5 qualifications has been scrapped. Instead the government will extend the current system of advanced learner loan funding for levels 4 to 6 until the end of summer 2030. This will give unregistered providers more time to apply for OfS registration in one of the two existing categories, though OfS is scheduled to consult in autumn 2025 on proposals to disapply some conditions of registration for providers in the further education statutory sector (which already has a regulator looking after most of this stuff).

Maintenance chunks

As expected, student maintenance support will be available on a pro-rata basis (depending on course, location, and personal circumstances) in an equivalent way to the existing undergraduate offer. Because this support is intended to deal with “living costs”, DfE has decided to continue to restrict availability to students attending in person – there’s nothing for online or distance learning.

Additional targeted grants (most likely this just refers to existing disabled students’ allowance and such like) will still be available – but there’s more to come on this later this year, alongside more guidance on maintenance generally. We can perhaps hope that a forthcoming announcement modifying the decades-old system (or even just the parental income thresholds) is playing a part in this delay.

That feeling of entitlements

Another area where things have mostly stayed the same is the personal entitlement for tuition fee funding equivalent to four full-time years (480 credits, currently £38,140) of traditional study – with the welcome clarification that where a provider charges less than the maximum the cash value rather than the credit value will be deducted from the total. Maximum borrowing is for 180 credits a year (which would just about cover a year of an accelerated degree). And for existing graduates (with the frankly wild caveats as before) there will be an entitlement to funding equivalent to unused residual credits.

But what happens when your balance reaches £0? No more learning for you? Not quite – a “priority additional entitlement” may be available (fees plus maintenance) in order to complete a full course in a small number of subjects (medicine, dentistry, nursing and midwifery, allied health professions, initial teacher training, social work).

For those who follow career paths that require five years or more of study (veterinary surgery, architecture part 2, an integrated masters in Scotland) there will be a “special additional entitlement” of up to two years, again covering fees and maintenance. There’s also additional entitlements for those who take foundation years, placement years, or study abroad years. It’s by-and-large a smoothing-out of some of the unintended consequences with existing provision where representations had been made.

Plus, importantly, the government will now play a part in mitigating circumstances – if you are resitting a year because of “compelling personal reasons” (illness, bereavement) you will have the costs of your study covered. And resits on longer courses will be covered anyway.

The credit transfer question

“The LLE and modular provision will provide a pathway to strengthen opportunities for credit transfer and learner mobility,” the new version of the paper states. While no-one would deny that the LLE could be a “pathway to strengthen opportunities,” especially given how tepid the phrasing is, there has still been essentially no progress on the thorny question of credit transfer.

The largely new section on “recognition of prior learning, credit transfer, and record of learning” sets out aspirational areas where the government thinks it can work collaboratively with the sector – to promote pathways between providers, to improve guidance for both incoming and outgoing learners, and to generally square the recognition of prior learning circle despite all the intractable problems therein.

Interestingly, DfE also wants institutions to embed all this into “broader strategies for widening access”. It’s not immediately clear how this will come off – but we get the note that this year will bring an update on “proposed changes that will start to embed this flexibility and greater learner mobility across LLE funded provision.” This might be a reference to the post-16 education and skills white paper.

To facilitate all this flexibility, DfE had previously said it would be introducing a “standardised transcript template.” Tellingly, this has now been revised down to “a standardised transcript as part of modular funding designation.” So it appears the plan is now to look at enforcing this standardisation for the (potentially scant) modular provision that the LLE will generate, while sidestepping the much bigger question of how portability between modules and larger qualifications including degrees will work. This is a substantial scaling down in ambition – and yet it’s still a complicated thing to get agreed implemented in little over a year.

What’s next

As is probably coming across, there is still an awful lot yet to be confirmed. Secondary legislation to implement the LLE fee limits and funding system still needs to be laid. Fee loan limits for non-fee capped provision are pending confirmation. The Student Loans Company needs to get its systems ready.

There will be another consultation too, in addition to OfS’ further education one. While it’s not mentioned in the updated policy paper, the accompanying provider preparation guide reveals that the Department for Education will consult on “learner mobility across LLE-funded provision in early 2026” (maybe this will be the moment when credit transfer finally gets sorted out once and for all). Opening a consultation in early 2026 when big chunks of the whole shebang are supposed to be ready to go that September does not necessarily inspire confidence.

And the drip-by-drip announcements about the policy plumbing of the LLE mean that it’s a long time since the government has really restated its belief that there is demand out there for modular provision, or committed to working to drum some up. Really it’s baffling why this week’s announcements haven’t been packaged up with the skills white paper, as surely they must form part of a wider vision. Some clarity within this about overlaps and interplay with the apprenticeship levy would have been welcome too.

The provider preparation guide entreats institutions to start thinking about how they will market modular provision, which is a tricky question given the absence of demand that pilots have demonstrated. But one of the examples given is particularly problematic:

if you seek to target mature students, do you need to start building relationships with local employers and/or recruitment agents, rather than only relying on existing recruitment channels?

This isn’t a new addition to the guidance – but since the last update, Bridget Phillipson has told Parliament that the government will “take immediate action on the use of agents to recruit students,” adding that “the government can see no legitimate role for domestic agents in the recruitment of UK students,” following the Sunday Times franchising investigation fallout. So DfE is at the same time banning the use of domestic agents – or at least it said it would – while acknowledging that recruitment to modular provision might be tricky without them.

It’s of a piece with much of the preparation guide – the responsibility to iron out the holes in the LLE’s business case is being passed onto providers. Supposedly over the rest of the year universities and colleges should be reviewing everything from accommodation to wrap-around support, while building up relationships with employers and potentially rewriting their academic regulations. All while plenty remains unclear at the sector level. It would be unsurprising to see providers reluctant to leap into the approvals process right away, and instead assess how others fare.

Given all this, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the ambition of the LLE has diminished a little bit each time the policies around it have been updated. We’re a long way from where we started.

Probably the most damning assessment you could make is that, were Labour to have opted to cancel the whole LLE and just allow students to take out loans for a handful of higher education short courses tenuously linked to industrial strategy priorities, the sector would be in a very similar situation to the one it is in now. And – given clear indications of lack of student demand, and common sense assessments of the general public’s appetite for more tuition fee debt wrapped up in confusing bitesize-but-lifelong repayment obligations – few would think it was a good idea.

The LLE is about more than just modular provision: there are significant benefits from per-credit fee caps, abolishing ELQ rules, the residual entitlement and the introduction of the personal account. The modular funding element is also broader than previously planned. The proposal set out in the 2023 White Paper was that it would initial only cover HTQs until some unspecified point in the future, and then be expanded to fund modules “where we can be confident of positive outcomes” over the longer term. Now modules of “traditional” qualifications will be included right from the start and with fewer controls than… Read more »