I’ve long been concerned about excessive university regulation and written many a post on Wonkhe about it. Things are already pretty grim for the sector but they are about to get a whole lot worse. More regulation looks to be on the way.

In the past three weeks already we have had new conditions from OfS on student number controls and now we have been presented with the Restructuring Regime (the latter possibly entertainingly named after a little remembered and short-lived prog rock group, an offshoot from an early line-up of Hatfield and the North in the early 70s). Also, just in, there is another OfS condition now out too. Truly, we are being spoiled.

The Restructuring Regime (the government paper, not the band, we’ve moved on now) is one heck of a prospectus packed into just 15 short pages (front and back covers, contents page and appendices included). Whilst principally concerned with providing a means of preserving (some) universities facing the most severe challenges in the face of the pandemic it is actually a crude winnowing device intended to provide support only to those institutions which do as they are told. But that’s not all. Look at part of the Ministerial foreword for example:

5. The conditions imposed as part of the Restructuring Regime will be designed to ensure those providers make changes that will enable them to make a strong contribution to the nation’s future. We need a future HE sector which delivers the skills the country needs: universities should ensure courses are consistently high quality and focus more heavily upon subjects which deliver strong graduate employment outcomes in areas of economic and societal importance, such as STEM, nursing and teaching. Public funding for courses that do not deliver for students will be reassessed. Providers will need to examine whether they can enhance their regional focus. I want it to be the norm for far more universities to have adopted a much more strongly applied mission, firmly embedded in the economic fabric of their local area, and consider where appropriate delivery of quality higher technical education or apprenticeships. And all universities must, of course, demonstrate their commitment to academic freedom and free speech, as cornerstones of our liberal democracy.

6. At this time of financial challenges, universities and other higher education providers must do much more to strip back bureaucracy, allowing academics to focus on the front-line. The growth of administrative activities that do not demonstrably add value must be tackled head on. The funding of student unions should be proportionate and focused on serving the needs of the wider student population rather than subsidising niche activism and campaigns. Vice-chancellor pay has for years faced widespread public criticism. And while excessive levels of senior executive pay may have been the focus of criticism, equally concerning is the rapid growth over recent decades of spending on administration more broadly, which should be reversed. For our part, we are actively considering how to reduce the burden of bureaucracy imposed by Government and regulators.

As this foreword makes clear, this is not just a last ditch loan offer with more conditions than you can count for those in the deepest trouble, it’s a message to the whole sector.

Only recently I was rehearsing my much repeated concerns about the dangers of excessive regulation together with my much maligned but highly scientific analysis (with a graph). The point in the piece is a simple one – there comes a stage where the more a government regulates an activity such as higher education in order to seek to direct it to do what it wants it to do, the less likely it is to achieve either its own or the government’s objectives. In other words the medicine applied to make it better actually ends up killing the patient.

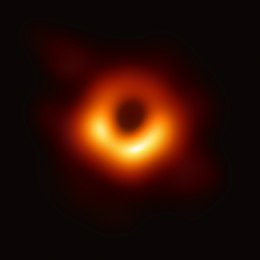

Over the event horizon

University regulation, as it grows and grows, requires universities to spend more and more time and money on compliance. Let’s try another inadequate homespun analogy (astrophysicists look away now): as the burden of regulation gets ever bigger there comes a point at which one part of the university will collapses in on itself to form a super-dense and massive regulatory black hole. And then other parts of the institution will be drawn in by the regulatory gravitational pull, spending more and more time and money on regulation until they too pass the regulatory event horizon and disappear into the black hole. As they disappear from view to be compressed into a regulatory nothingness they go through a process of what theories describe as regulatory spaghettification – where every rule and process is extended to an infinite degree for what feels like eternity and no actual education remains, only regulation. Eventually then whole universities will rush headlong into the regulatory black hole too, our entire university system will be squished into nothingness and we will reach the singularity of all that there is being the most intense regulation imaginable. No education but total regulation.

Not a pretty picture. But the point is a serious one. If the burden of regulation continues to grow and government continues to insist on more direction of and control over university activities we will reach a point where the cost of regulation itself and the expense for universities of complying with the regulation actually exceeds the cost of the activity regulated. It sounds absurd but at the moment it feels like the direction of travel. Obviously this is just a rather provocative theory but I for one don’t want it to be proved.

Something wicked this way comes

The effects of excessive regulation of academic matters on university life can be toxic. I am reminded of when, as a relatively junior administrator, I was working with School of Modern Languages at UEA on its preparations for what was then TQA and had a series of difficult encounters with academic colleagues. Most notable of these led to me being on the receiving end of a tirade from a certain Professor W G Sebald about the appalling nature of the regulatory system which he saw me as promoting and implementing as an agent of the state. (I found this pretty demeaning as a result of which I determined never to read any of his books, a decision only I suffered for having realised many years later how excellent they were.) Much regulation has a similar negative effect on universities.

There is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the Minister’s regulatory line here – no governments have done more to increase the burden of regulation on higher education than those in power since 2010 (apart from, arguably, the Major government) and yet here we are being told to “strip back bureaucracy” the vast majority of which exists in response to the external requirements of government and its agencies. At the same time as these exhortations to reduce administration there are strong suggestions of more on the way, relating to graduate employment outcomes, free speech, students’ unions, senior staff pay, ‘low quality courses’ and greater orientation to local economic needs. And if you are in a university looking for that additional financial support for restructuring then you will have to develop and then comply with a comprehensive restructuring plan too. So, it’s a heady mix of pandemic-related justifications for interventions and a whole series of historical scores to be settled.

In short it looks like a tidal wave of regulation is coming our way. And none of it good. The sector is in for some significant regulatory pain and expense.

I can actually picture the shiny new student building on campus being torn apart as it crosses the event horizon and undergoes regulatory spaghettification. Brilliant.

Isn’t the correlation here really between regulation and massificiation? The university sector wanted to be bigger and better funded, and it is both. Like any public service, that leads to greater government interest in what the public is getting for its substantial monetary investment. All public service professions whose services become massified subsequently moan about overbearing governments asking what they’re up to – it was the same with doctors in the decades after the NHS was established, and with teachers a few decades after education became universal. If the sector wants to be less regulated and more autonomous, then it… Read more »

Every week some new abuse comes to light yet no prosecutions and what is £1 Billion pa public investment in research actually achieving? Someone needs to be asking these kinds of questions – much more oversight and accountability need and if that mean more regulation, so be it.