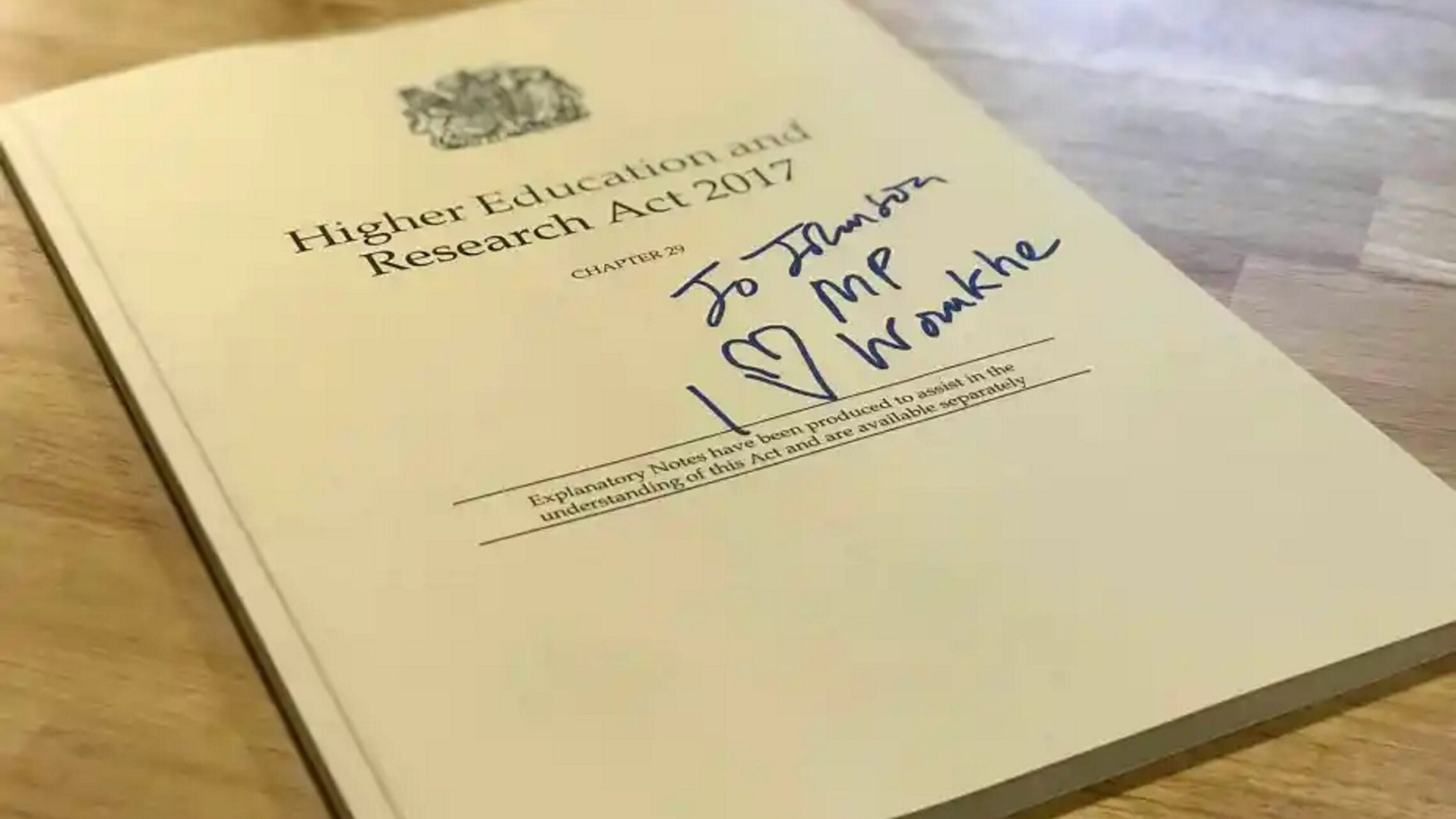

Five years ago, on 29 April 2017, what is now the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 received Royal Assent.

It is the scaffolding around which higher education regulation in England is built, and was seen at the time (by many) as the “most important legislation for the sector in 25 years”.

However, even the finest and most generation-defining of acts meet with problems between promulgation and implementation – for this reason most Acts of Parliament can expect a “section 40 review” (or “post-legislative scrutiny”) between 3 and 5 years after they enter the statute book.

How it works

The responsible department – in this case the Department for Education – needs to submit a memorandum to the relevant Commons Committee – the House of Commons Education Committee. This memorandum takes the form of a “command paper”, which must be presented to parliament while it is in session.

The substance of this memorandum is a preliminary assessment of the way an Act has worked in practice – based on “objectives and benchmarks identified during the passage of the bill and in supporting documentation”. It is meant to tie together any reviews required by legislation (stuff like the triennial review of designated bodies, or the section 26 review of the TEF) with the department’s own thoughts on how well the Act is doing what it has been designed to do.

It’s not a requirement in all cases – finance and consolidation Acts, Acts that have already been repealed, Acts that have already been the subject of a committee inquiry, and Acts of “limited policy or practical significance” can all (with the agreement of the Committee in question) forego this process. Again, with agreement from the Committee, submissions can be brought forward or delayed.

On receipt of the memorandum, the Committee can then decide whether or not to conduct fuller post-legislative scrutiny in the same way as it decides to carry out any other inquiry.

The gap

Five years after assent was granted to HERA, none of this appears to have happened. My understanding is that DfE might squeeze this one out a bit late – publishing towards the back end of the year, assuming nothing else crops up.

This delay is perplexing, because HERA is clearly a pivotal piece of legislation – and one that (not least because the government proposed amending large chunks of it in two bills this session) may not now be fit for purpose. Given that the regulatory activity undertaken by the Office for Student is so closely linked to HERA, given that OfS has sought and been granted new regulatory powers (not least via the Skills and Post-16 Education Act), and given Jacob Rees-Mogg’s new bonfire of the quangos, the English higher education sector’s favourite arms-length body may be ripe for review too.

With Thursday’s prorogation ceremony (and those Norman French interjections we all know and love) now complete and the five year deadline missed, in my usual spirit of helpfulness and public service I thought I’d dig out the template and have a crack at drafting a memo myself.

Dear Mr Halfon

The guidance and template are clear that a memorandum like this does not constitute the full legislative review – rather, it serves to point committees to areas where they may (or may) not wish to take a more in-depth look. The headings I’m using below are minimum requirements for this kind of memorandum – DfE could very easily expand on this skeleton.

Summary of the objectives of the Act

What was HERA for? Let’s have a look at Justine Greenings’s introductory speech at Second Reading (for younger readers – Justine Greening was once Secretary of State for Education). Though there’s a case for going back to the various green and white papers, the way the bill was introduced to Parliament seems like a good summation of the way it rose from the policy morass. Front and centre we see a continuing government commitment to widen and grow access to higher education, to offer financial stability to providers, and to “level the playing field” for creating new universities to support this expansion. There’s also a promise to “build in quality” at every regulatory stage.

A new Office for Students was proposed to put “students at the heart of higher education policy, as they should be” and reduce regulatory costs via “risk based” regulation. The OfS would be able to fine, deregister, or otherwise censure providers that breach conditions of registration – while safeguarding institutional autonomy and academic freedom. That said, it would also have powers to enter and search providers with a court warrant.

A new, single, body for research – UKRI – would draw together existing research councils, Innovate UK, and – as Research England – the former research and knowledge exchange functions of HEFCE. This was particularly to drive inter- and multidisciplinary research by providing a single strategic framework.

In concluding the Second Reading debate, then Universities Minister Jo Johnson added a few more points of note. The Bill was also supposed to address recent falls in student perceptions of value for money and less than optimal graduate outcomes. He also made clear his expectations that an assessment of teaching quality (the TEF) should be linked to provider income.

Implementation

Acts are implemented via a paragraph towards the end of the text, helpfully labelled “commencement”, which sets out when a section would come into force, usually on the day the act gains Royal Assent, on a prescribed day, or following publication of secondary legislation. There were six main pieces of secondary legislation that brought the Act into law – here’s a summary of what happened when, from the The Higher Education and Research Act 2017 (Commencement Order No. 6) Regulations 2020.

There are a handful of measures in the bill that have still not been implemented (as of May 2022):

- Sections 86 and 87 refer to the long awaited “alternative payments” provisions – Sharia-compliant loans. DfE continues to claim to be working on the detail of these measures, but we first started talking about them during the last Labour government so I’m not getting any great sense of urgency.

- Section 52 has not come into force – meaning that the old (FHEA1992 s76) provisions as to degree awarding powers are still in force in England (alongside the new provisions in s42-49 of HERA). It’s unlikely, but the Privy Council is still – technically – allowed to bestow degree awarding powers. So if OfS says no, you may have another route.

- And section 8 of Schedule 12 (which refers to the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970) has not come into force, meaning that if the Secretary of State ever does any thinking about the need for an Institute for Hearing Research as directed in section 24 of the 1970 Act he or she would need to somehow take their ideas to the no-longer-a-thing Medical Research Council.

Secondary legislation

It’s not just commencement and consequential changes that lead to statutory instrument fun – primary legislation like HERA lends itself to all kinds of SI and there have been 113 of them since 2017.

Aside from the stuff we’ve already covered, the majority of these refer to fee and student support amounts – though there is a sprinkling of structural interventions to set up things like the OfS register, access and participation plans, and information sharing. Institutions that have gained degree awarding powers will have their own regulation, and there’s also regulations relating to registration fees for providers.

DfE would here have to list all of these and set out briefly what they do. I’ll just briefly note that registration fees still remain ridiculously high, fee limits have not risen with inflation (meaning a real terms cut in the unit of resource), and maintenance support levels have gone from inadequate to a breaking national scandal during the period that the Act has been in force.

Legal issues

The successful legal challenge made by Bloomsbury College, concerning the regulatory activity of the Office for Students, does not strictly speaking relate to the text of the Act but is a notable illustration of the way OfS has not always used the powers it has been granted in ways that had been anticipated. This issue was addressed via the Skills and Post-16 Education Bill, as was a linked issue related to the need for legal protection of the detail of investigations or other concerns about particular providers (an issue first noted by the OfS itself).

If we see related legislation as an indication of deficiency in HERA we should note that there’s been a need to define “module” in legislation to prepare the ground for the Lifelong Loan Entitlement, and this has been coupled with associated measures to ensure that OfS doesn’t create a data provision burden.

The need to add measures to address essay mills could also be seen as a failure of HERA to address an issue that was already widely discussed at the time.

And we need – sorry – to mention this session’s other two higher education bills. The new research council, ARIA, was designed to address a perceived weakness in UKRI (whether or not this was an actual weakness is up for debate), and the existence of Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill within the national discourse surely suggests the measures in 8(c) of HERA (and elsewhere) are not enough to deal with the current national free speech emergency we are facing (and that HERA should probably have included a specific director and complaints mechanism for this purpose).

Other reviews

The big one here is the report on the operation of the Section 25 Scheme (or TEF as we still know it), published as the Pearce Review substantially after the “initial period” of one year specified in the Act. The review drove a coach and horses through the pre-existing operating parameters of the TEF – criticising in particular the statistically unsound use of outcomes metrics, the downplaying of qualitative evidence, and the inane “olympic medal” nomenclature. One side effect here is that to widespread apathy a Section 25 scheme has only run in two of the five years HERA has been on the statute book.

OfS has published annual reviews of its operation as required in Schedule 1, but these have not generally included the section 38(c) requirement to examine the provision of arrangements for student transfers despite renewed ministerial interest in this issue. We have not – yet – seen the publication of triennial reports relating to the operation of the designated quality and data bodies but these are due very shortly.

UKRI has also provided an annual report each year, and alongside this we have seen numerous other reports and ongoing reviews of aspects of the wider research ecosystem.

The Commons Education Committee reviewed Value for Money in Higher Education during the 2017-19 session – making recommendations on changes to the funding model, the regulation of senior staff pay, measures to improve degree apprenticeships, changes to admissions processes, the reinstatement of means tested maintenance grants, and improved applicant information and support.

Some of these recommendations were taken forward in the Review of Post-18 Education Fees and Funding, which included the Augar report and the government’s response to it. Parallel to this we saw a DfE consultation on admissions that eventually came to nothing.

The Office for Students has published substantial changes (supported by a large number of consultations) to the way it regulates higher education. Though the initial regulatory framework was not a part of HERA, it drew closely on the measures and intentions enshrined within the Act – the changes to regulation underway see OfS moving steadily away from the regulatory model as originally envisaged.

(the good bit) Preliminary assessment of the Act

HERA as a whole has held together better than anyone could have expected, but the world it was designed to bring about has not arrived. Specifically, Jo Johnson’s idea that there were hundreds of new private higher education providers ready to join the sector, and that their entry into the market would increase competition and innovation, has been proven false. We’ve seen a fair number of providers enter the regulated part of the sector – which has been very welcome – though the genuinely low quality providers have remained outside it while still teaching students on behalf of registered providers.

A regulatory system designed to spur sector growth now seems ludicrously out of place as DfE are happy to promote literally anything else in preference to higher education. The new tastes for shorter, vocationally oriented, courses below degree level has signalled the need for new legislation.

The OfS approach to regulation has become increasingly instrumentalist, with the regulatory body keen to flush out the remaining vestiges of academic responsibility for and oversight of quality and standards in favour of a 2010 style dashboard approach. TEF, arguably, has failed to reshape the market and to provide information to applicants – the minister has recently announced plans to see other outcomes data included within course publicity.

More fundamentally, OfS’ design as a risk-based, customer interest supporting, market regulator has clashed awkwardly with the need to respond to ministerial whims based on whatever made them drop the marmalade knife while reading the Telegraph over breakfast. There has been palpable frustration with a regulatory inability to take direct and immediate action – while ministers have also railed against an accretion of their own policies contributing to regulatory burden.

Is HERA fit for purpose?

The designation of independent and respected data and quality bodies was designed to take fundamental issues of quality assurance and data collection out of politics, to allow for UK-wide consistency of practice, and to provide stability and dependability for the sector. In both cases relationships between these bodies and the regulator have deteriorated rapidly – with OfS increasingly calling the shots. The funding model for both of these functions is not fit for purpose – the use of mandatory subscriptions to cover basic operations have left both organisations struggling to work flexibly and develop their operations.

The English quality assurance regime has frequently been in danger of losing the prestigious international ENQA seal of approval, the data collection operation has been subject to numerous restarts and reconsiderations of a long overdue update of processes (moving from the much loved HEDIIP to the near-universally reviled Data Futures – and spurring an ad hoc DfE working group).

Outside of the OfS (which as above would also be subject to review under Jacob Rees-Mogg’s latest attack on arms-length bodies) the government has recently announced changes to the way people will access fee and maintenance loans, changes to the repayment of these loans, and has proposed methods to limit access to higher education. The government has yet to address the student maintenance issue in the face of a cost of living crisis, despite sensible recommendations from Augar.

In contrast, there has been less drama around UKRI – ARIA, Horizon affiliation and the cuts to international funding, notwithstanding – though we are only a couple of weeks away from the REF and who knows what response we’ll see from that (I’m imagining numerous groups perusing submitted work for evidence of “wokery”).

In conclusion

Looking back to ministers’ initial comments at second reading I’d argue that the establishment of UKRI has been a (qualified) success. But many of the other measures have either failed to work on contact with reality, have gradually become detached from their original purposes, or have been superseded by an unprecedentedly rapid shift in government policy.

There have been a lot of conversations about higher education in general over the years since HERA – politicians and sector leaders have tended, however, to take issues in isolation rather than to consider the overall legislative underpinning of the Act. A review like that conducted by Philip Augar, for instance, considered fees and funding in isolation. We need something a bit more wide ranging.

What should happen next?

One a memo like the one I’ve drafted above is received, the Education Committee should consider whether to undertake fuller scrutiny of the way HERA has worked in practice. It would then run an inquiry in the usual way – calling for evidence and interviewing witnesses before writing a report that would be responded to by the government.

I’m not for a second suspecting such a report would make a great deal of difference to current government policy, but it would highlight current issues with the way the sector is administered feels like the best way to push for changes and provide the evidence required for the re-evaluation of current approaches. It would be good, in other words, to have all this stuff on the record – and to drag the appropriate people in to ask just how we have ended up in the mess we are in.