Towards “intelligent regulation”?

HEFCE last year published its business plan to 2020 in which it set out its ambition to be an “intelligent regulator” –

A successful and sustainable sector which embraces many different types of competing provider requires intelligent regulation if it is to retain its reputation.

But is this what we need? Maybe. But the starting point should really be reducing the burden of what is really rather less than intelligent regulation. The Green Paper is concerned with freeing up regulation in part of the system – to facilitate access to the sector for new entrants – but offers a plethora of additional regulatory measures elsewhere. (And of course the last thing we actually need to do is make it easier to establish universities. It should be difficult).

Dennis Farrington writing here on Wonkhe identifies the legislation which would be required to implement the proposals contained within the Green Paper. Many welcome the possibility of legislation (which is looking more and more likely) and may lead to some helpful tidying but is more likely create substantial future work for lawyers in resolving contradictions in the resulting mess. Even without legislation the range of proposed measures will just add an extra layer of complexity. The BIS Select Committee’s comments on the proposed TEF, just published, don’t give any grounds for optimism in terms of the reduction of the overall regulatory burden

So the Green Paper implementation, whether it is through primary legislation or not, is unlikely to end well though and my concern would that, whatever happens, we will end up with more, and more costly, regulation for an already over-regulated sector.

A vast landscape

Apart from the occasional reduction in the burden, as in the ending of TQA for example, the trend is still upward. We still have an extremely comprehensive (overly so I would argue) quality assurance architecture for teaching and learning, a huge number of data returns and information which has to be provided to government and other agencies, the incredibly detailed Research Excellence Framework, the full range of wider non-HE regulation, financial assurance requirements and additional protection for students. It’s a vast landscape of bureaucracy.

Browne-field site v Green belt

The Green Paper regulation propositions do not seem wholly dissimilar to the Browne review of 2010 which in section 6 made a number of proposals for a new regulatory set up:

The higher education system is currently overseen by four bodies: HEFCE, QAA, OFFA and OIA. These will be replaced by a single Higher Education (HE) Council. It will take a more targeted approach to regulation, with greater autonomy for institutions.

The Council will be independent from Government and institutions. It will have five areas of responsibility:

- Investment – identifying and investing in high priority courses; evaluating value for money; dealing with the unexpected, with the primary aim of protecting students’ interests

- Quality – setting and enforcing minimum quality levels across the whole sector

- Equity of access – making sure that individual institutions and the sector as a whole make measurable progress on admitting qualified students from disadvantaged backgrounds

- Competition – ensuring that students get the benefits of more competition, by publishing an annual survey of charges, and looking after the interests of students when an institution is at risk

- Dispute resolution – students can ask the Council to adjudicate on a dispute that cannot be resolved within their institution and provide a decision which binds both sides

Nothing much changed in this domain though as the post-Browne focus was very much on fees and funding rather than regulation.

All gone to HEC

Not to be put off, the Higher Education Commission in October 2013 made a number of recommendations for changes to the regulation of HE including:

- The creation of a new, overarching regulator, building on HEFCE’s remit (renamed the Council for Higher Education – CHE. The CHE should incorporate OFFA, OSL (formerly SLC) and a new body, OCID (Office for Competition and Institutional Diversity). Responsible for ensuring complementarity of bodies across a pluralist system, the CHE should have contractual relationships with QAA, UCAS, and HESA.

- The development, by the new lead regulator (CHE), of a Common Regulatory Framework that can be applied to a range of providers to varying degrees, dependent on their provision and funding arrangements. The Common Regulatory Framework would create a kite mark to be awarded by the CHE, which institutions would receive once they had undergone a successful QAA review and subscribe to the OIA.

- Greater protection for students through the formation of a ‘protection’ or ‘insurance’ scheme, coordinated by the lead regulator, paid into by all providers, to insulate institutions against possible future financial difficulties or failure.

The report acknowledges the ‘long and largely successful self-regulatory history’ of the HE sector as a whole, with academic norms, peer review and sector-wide representatives remaining ‘bulwarks’ against poor performance. It further argues that the principle of regulatory pluralism that currently defines higher education should be continued, with a new over-arching regulatory body providing effective sectoral coordination, rather than centralist control.

However, the report stresses that in England’s increasingly open and market-driven HE sector, new alternative providers of higher education are not being picked up by the regulatory regime, putting students and the sector as a whole at risk. The report argues that effective regulation also has an important ‘positive focus’ and would have ‘strong developmental effects’ for the sector by increasing investor confidence and encouraging innovation across institutions

A salutary warning here about the risks of too light a regulatory regime in relation to new providers. But also perhaps a touching faith that regulation can somehow foster innovation in education. This seems to me very hard to imagine. The absence of excessive regulation can help to ensure that innovation is not stifled but it does seem surprising to argue that regulation can promote it.

There’s more

So back to the current realities. The HEBRG back in 2011 looked at the non-HE regulation landscape and noted that universities are also subject to a much wider set of regulations too, including in the following areas:

- Corporation tax returns

- Equality and diversity

- Employment law

- Freedom of information

- Health and safety

- Estates and infrastructure

- Procurement

So, lots more regulation for universities to deal with.

Quality Counts

HEFCE summarises the current QA regime as follows:

QAA carries out a range of reviews to provide public assurance on academic standards and quality at HE providers. Quality assurance reviews build on HE providers’ own internal and external quality assurance arrangements. Such arrangements include:

• student feedback

• corporate governance

• internal and external peer review

• external examiners

• course validation

• complaints and appeals procedures

• annual monitoring processes

• internal audit

• approval of validation and franchising arrangements with other providers.

QAA conducts the following forms of review, which take place within regular cycles or at intervals within a rolling programme:

a. Higher Education Review aims to inform students and the wider public whether a higher education provider meets expectations for:

• the setting and/or maintenance of academic standards

• the quality of learning opportunities

• the provision of information that is fit for purpose, accessible and trustworthy

• the enhancement of the quality of its higher education provision.

That’s not the full picture though. There’s more too including in relation to transnational education and oversight of institutions which wish to recruit international students in the UK.

Making it better

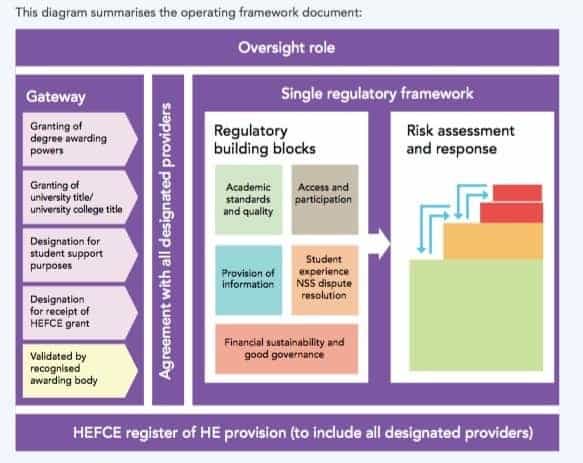

The Higher Education Better Review Group produced a two year review in 2014 which, among other things, noted an operating framework which showed how things work:

The operating framework document is the first time England’s higher education regulators have collectively produced a coherent, integrated explanation how the roles of various organisations fir together to form the fabric of higher education regulation in England. It is intended to be a work in progress and RPG assumes that it will require regular updating.

And that’s not all

There’s plenty more where all that came from. For example, just off the top of my head we have:

- Reviews of teacher training provision and nursery services by Ofsted

- Many different professional and statutory bodies from the Nursing and Midwifery Council to the British Psychological Society and from the Institution of Civil Engineers to the General Medical Council.

- Access agreements with OFFA

- DELHE and HE information provision to Unistats

- Student complaints via the OIA

- Student number controls (although these have recently been lifted)

- Regulations on work with animals under the 1986 Act

- Regulations governing work with human tissue

- Governance – where we have the example of the Scottish Government’s desire to dictate election arrangements for governing body chairs among other things

- The CMA interest in undergraduate recruitment by universities

- The Prevent duty

- The 1986 Education (No. 2) Act which covers, among other things, universities’ responsibilities to ensure freedom of speech for visiting speakers.

- The Further and Higher Education Act 1992 which, in addition to enabling polytechnics to become universities, introduced a requirement that funding councils “secure that provision is made for assessing the quality of education provided in institutions for whose activities they provide, or are considering providing, financial support”

- The Education Act 1994 which introduced lots of regulations governing students’ union operations.

- The changed financial memorandum between institutions and HEFCE

- TRAC

- The requirement for universities to draw up a Student Charter

- Charities regulation.

- On top of this the the 2010 Higher Education Better Regulation Group (HEBRG) survey on data collections identified approximately 550 lines of reporting across the sector.

It’s a huge burden.

Costing a packet

Back in 2009 PA Consulting produced a report (its second) on the costs to the HE sector of regulation:

We examined the experiences of 20 HEIs, selected to be representative of the wider sector, and their responses to the requirements of sector-specific regulators. Our 2004 review had estimated the costs of compliance with these requirements at around £240m (in 2008 prices). This estimate was substantially lower than the equivalent finding from our first study in 2000, but nonetheless was seen by the sector as higher than necessary and therefore unduly burdensome. Our current study found that the incremental costs to institutions of compliance with sector-specific requirements have continued to fall, broadly in line with HEFCE’s stated objectives, and are now some 21 percent lower. On our best estimates of like-for-like comparison, the 2008 equivalent costs to the 2004 estimate were around £190m across the sector. On a more sophisticated basis, taking account of institutions’ recognition of the activities and costs they would undertake as ‘business as usual’, the aggregated incremental costs in 2008 were calculated at around £167m across the sector.

This struck me as a significant underestimate then and looking back seems even less credible. The cost of compliance, given the growth in regulation, can only have grown. And it was and remains incredibly costly.

For example, this more recent estimate of the cost of just one aspect of the regulatory regime (in 2013) shows a more realistic assessment:

The Higher Education Better Regulation Group (HEBRG) has released research on the costs and benefits of the current student visa regime on UK higher education institutions. The research estimates that the total cost to the sector in 2012-13 was £66,800,910. This is more than £26M higher than the most recent estimates.

Regulation costs. A lot.

Regulation – it’s all bad

A few more final points of annoyance for me about the current regulatory regime:

- There is no assessment of risk here – this is actually on the whole a low risk sector and some institutions are even less risky propositions than others.

- There is no proportionality either – the burden significantly overstates the nature of the risk.

- There is no reduction in regulation for those institutions with an excellent track record.

- There is no attempt at an evaluation of the cost versus benefit of the regulation.

- It runs completely counter to the current government’s rhetoric of market and choice.

- It is not a level playing field, it never has been, never can be and never will be (it’s always going to be a bit difference as noted in this blog post from a few years ago on the subject https://wonkhe.com/blogs/the-imperfect-university-do-we-need-a-level-playing-field/ ).

- It provides many a gift to league table compilers who can select from the data collected (and arguably become part of the regulatory burden themselves as institutions compete for advantage).

So, The current regulatory regime does not in any way resemble risk-based assessment, higher education is fundamentally a low risk operation. As noted above universities already have a bucketful of regulations common to many public organisations and businesses as well as all the sector specific rules. And it all costs a fortune. It remains an iron rule that regulation only grows ultimately. There may be an occasional dip, such as in the ending of TQA, but the trend is still relentlessly upwards and it is now inversely proportional to the size of public financial contribution.

Higher education delivers a massive payback – direct and indirect – to the economy, to society and to individuals. The growth in regulation seems to be completely at odds with the government’s market rhetoric – it is logically, intellectually and economically incoherent.

I fought the law

Will legislation happen? I don’t know. I’ve often been disappointed by the meekness of the sector in resisting regulation or indeed our enthusiasm for extending it. We are our often our own worst enemies – too frequently we naively add to the regulatory burden ourselves – either internal ‘gold-plating’ of our own institutional processes, overlaying these excessive external demands with even more – or we offer insufficient challenge or even contribute actively to extending the reach of external regulators.

Part of the enthusiasm for new legislation is the desire by some for a more neat and tidy regulatory landscape. It’s sensible to be a little skeptical about this. Legislation rarely results in reduced regulation and indeed tidiness can often be a long way from either effectiveness or efficiency in regulatory terms.

In 2004 I commented on the sector’s anticipatory penitence – whereby we were always introducing new regulations ourselves for fear of worse being imposed – and our huge concerns about the introduction of an Ofsted regime for HE. This looked tyrannical a decade ago but perhaps looks less frightening in today’s extremely highly regulated environment.

Returning to the HEFCE plan to 2020 noted at the beginning of this piece

And fundamentally we are working with BIS, Universities UK and others on the building blocks of future legislation to ensure that we have a risk-based, proportionate, and comprehensive regulatory system in place fit for the future.

This is surely what the sector needs. We are though a very, very long way away from it at the moment. And we are moving in the wrong direction.