The headline on the front page of the Telegraph literally says that there will be £500,000 fines for “Mickey Mouse” courses.

Or, put another way, individual subject areas within each university are going to have to meet minimum continuation, completion and progression rates. Or else.

That’s the twenty word version of a long awaited and whopping 72 page, 28k word proposal from the Office for Students (OfS) on quality and standards in higher education.

We’ve told the backstory to the emergence of what we’ve called the “B3 Bear” on the site over the past year in several stages, and will attempt to not repeat the detail here – but if you fancy a detailed trip down memory lane, there’s the moment where we started to analyse provider registration refusals last September, the moment where the role of statistical performance baselines started to become clear last November, the relationship between these issues and controls on student numbers in February, and the stories both of when OfS won in court on this agenda in March, and when it lost its appeal in July.

One famous fan

Condition B3 in OfS’ regulatory framework has so far proved controversial. It’s one of the quality ones, where the provider must “deliver successful outcomes for all of its students, which are recognised and valued by employers and/or enable further study”. In the initial registration phase it managed to generate 147 “interventions” – 50 formal letters, 77 lots of “enhanced monitoring”, and 20 specific (and public) conditions of registration – as well as playing a starring role in a number of the outright registration refusals that have been made public.

Yet the inner workings of OfS’ metrics based regulation were a riddle wrapped in an enigma for most of us, not least because the way they were applied in those initial evaluations of providers trying to get onto the register were partially hidden – something that became a key point of contention in the court case over the Bloomsbury Institute.

There’s an old Transport for London “Awareness Test” that comes to mind – you’re busy counting a group of youths making rapid basketball passes, until the voiceover asks if you spotted the moonwalking bear that was moving across the screen all along. Once you see it, it’s so preposterous that you wonder how you ever missed it. And so slowly, we’ve been tracking the emergence of the B3 bear – OfS’ set of metrics minimums, into the sector’s consciousness ever since we got hints about their nature a year or so ago.

It’s all so obvious once you see it. For example – in some ways what’s most notable about the new proposals from OfS is the unusually supportive comment from universities minister Michelle Donelan:

We want all university students, regardless of their background, to benefit from high quality, world-leading higher education. Our manifesto promised to explore ways to tackle low quality courses, and we continue to support the Office for Students on this. I am pleased that the OfS aims to raise the bar on quality and standards. We must have robust regulation of our higher education system, which includes strong action if standards slip and principles which protect students’ interests.

That’s right – at least in part, here OfS makes the first steps towards providing ministers with a handy technical answer to that oft-considered political question – what is a “low value course?”. The B3 bear is out of hibernation and on the hunt for Mickey Mouse (courses). And the wider implications could be huge.

The consultation itself is, to say the least, viscous stuff – even more so than usual given that it in part carefully responds to OfS losing that case in the Court of Appeal on this regime back in August (without ever mentioning the episode), so every i is dotted and every t is crossed here.

In a nutshell

But the complexity of the consultation document belies a pretty visceral simplicity. OfS will define both unacceptably low “quality” and poor “value for money” by setting minimum outcomes to be achieved, at subject level, in every mode, across all providers. And in doing so it will offer ministers a tantalising chance to control the flow of funding to higher education by intervening on where those minimums are set.

There are four main proposals here – one on the definitions of “quality” and “standards”, the big one on numerical baselines for student outcomes, plus stuff on the indicators and approach OfS uses for “risk-based monitoring” of quality and standards, and how it will intervene if it finds or suspects a problem.

But before it gets there, a policy stall is set out with some clarity that explicitly addresses some of the issues in the Bloomsbury court case:

We do not accept that students from underrepresented groups should be expected to accept lower quality, including weaker outcomes, than other students. We therefore do not bake their disadvantage into the regulatory system by setting lower minimum requirements for providers that typically recruit these types of students.

The argument here is that benchmarking might make sense in some aspects of the way in which we “judge” a course or a provider – perhaps by assessing the amount of “value added” for a particular type of student that traditionally under performs, or by looking at employment outcomes in a particular context. But OfS is saying that judging and assessing positive performance (in exercises like the TEF) is different to judging minimum performance.

Much of the sector expressed dismay at Michelle Donelan’s NEON conference speech in July when she said:

The 2004 access regime has let down too many young people… too many have been misled by the expansion of popular sounding courses with no real demand from the labour market. Quite frankly, our young people have been taken advantage of – particularly those without a family history of going to university. Instead some have been left with the debt of an investment that didn’t pay off in any sense.

And yet here, OfS frames its approach to regulation almost identically:

Some providers recruit students from underrepresented groups… while they may provide opportunities to access higher education for such students, we also see low continuation rates and disappointing levels of progression to managerial and professional employment or higher-level study, suggesting that students may not be being supported to succeed. This is where our regulatory attention needs to focus.

Make no mistake – this is a technical solution to a political agenda and a political problem – which depending on your perspective is either how a sector that gets a truck full of public money should be treated, or a terrifying encroachment into both the sector and students’ freedom and autonomy to choose each other in a market.

A baseline is dropped

Let’s look first at the baselines. As noted above, this is pretty simple – OfS will define its requirements by setting numerical baselines for acceptable performance for indicators relating to continuation, completion and progression to managerial and professional employment or higher level study. It does this within condition B3 in its regulatory framework:

The provider must deliver successful outcomes for all of its students, which are recognised and valued by employers, and/or enable further study.

It has some justifications for picking the three metrics:

- OfS says continuation rates help it understand whether a provider is recruiting students able to succeed through the early stages of its courses, with the appropriateness of recruitment and student support under the spotlight;

- It says completion is similar and provides a look over the whole student lifecycle. This difference in focus means that there will not be a direct, linear, relationship between a provider’s continuation rate and its completion rate.

- Meanwhile progression tells OfS whether a provider’s students have successful student outcomes beyond graduation.

And before everyone piles in with yebbuts over employment not being the be all and end all on that last one, OfS has its defence in early:

Although individual students will define their success beyond graduation in relation to their own goals and motivations, it is important to ensure that graduates are achieving outcomes consistent with the higher education qualification they have completed.

Low rates of progression into employment and higher level study destinations commensurate with the qualification they have completed may suggest that a course has not equipped students with knowledge and skills appropriate to their intended learning aims, or that students were not effectively supported to transition into the workplace.

So there.

Micro-regulation

As previously signalled, this will all be done not just at aggregated provider level, but at subject level, and over different groups of students too. Officially that’s about rooting out “pockets” of poor performance and stopping providers from playing the averages, but unofficially it addresses some of the rank inconsistencies present in only using provider level data.

As we’ve noted before, a small provider running only business studies courses might be refused registration on the basis of its outcomes, but a large post-92 university might have even more students doing business studies courses getting worse outcomes – but at present they might be balanced out by better outcomes in the portfolio.

OfS reveals that there were almost 65,000 students in 2018-19 on courses that would not have met the numerical baselines it used for registration if it had assessed each of those “courses” against the relevant current baseline, and that means that:

Around 3 per cent of the total student population in registered providers in that year were on courses that did not meet the numerical baseline we had put in place.

This proposal goes some way to addressing that, although it takes you five seconds to start imagining the ways in which some will seek to start to game this system.

We’re also not really sure what it means by “course” here, and the 65k figure is never justified, although we do discover that the starting point for a more detailed consultation will be subject groups as defined by level 2 of the Common Aggregation Hierarchy, with an aim to align as far as possible with subject definitions that might end up used within any subject TEF.

Coming up

The other important thing to note here is that we’ll likely not just see the minimums applied at subject level, but also see those minimums rise – at least in part because that’s what the Secretary of State said should happen in last year’s letter to OfS:

For example, we set a numerical baseline for continuation for full-time first degree students of 75 per cent and this means that we accepted in principle that a quarter of a provider’s students could fail to progress from the first to the second year of their course. We do not consider that to be an appropriate minimum requirement in a high quality higher education sector where students and the taxpayer are the majority funders. In proposing this approach, we are having regard to, among other things, guidance from the Secretary of State that welcomes work by the OfS to develop even more rigorous and demanding quality requirements.

That’s sort of where things get interesting. The consultation nods towards public opinion and public perception being important in the mix when setting those baselines – and what are politicians if not expressions of it? If a Secretary of State writes and says “you’re on 78 per cent now but I’d like you to move to at least 85 per cent”, can OfS ignore the edict?

Unintended consequences

And once you’re there, the age old question facing providers subject to metrics-based regulation kicks in. Do you a) improve the provision and the support around it to improve the metrics, or b) drop the provision and focus your “portfolio” on better performing courses? It’s no coincidence that Universities UK is (re)publishing proposals on “portfolio reviews” on the same day that this is out.

If this kind of reform in the further education sector is anything to go by, there will be plenty of Option b) around in the name of “not setting students up to fail”, which will deliver the unfortunate by-product of further restricting student choice for those not prepared or able to move away from home.

And it’s not mentioned, but could we end up seeing different baselines for different subjects? It may be reasonable to hold providers to identical minimum performance for all subjects in a deep recession. It may also be reasonable to hold some subjects (and, by implication, some professions) to higher baselines.

Some further technical detail of note includes:

- OfS will publish metrics for individual providers to show their performance in relation to the numerical baselines, and will also publish sector-level metrics to enable stakeholders (and league table compilers) to better access and understand the data on which decisions are based and the performance it expects providers to achieve;

- It’s intending to only look at awarding gap data in the context of B4 (“qualifications awarded to students hold their value at the point of qualification and over time”) rather than here in B3;

- We will still get to see so-called “split indicators” to show the performance of different student demographic groups within each level and mode of study for students who are taught or registered by a provider. We’ll see these in aggregate, over a time series of up to five years, but not separately for each year of the time series. We’re likely to get age, POLAR quintile, English Indices of Multiple Deprivation quintile, ethnicity, disability, sex and domicile.

- OfS solicits views on whether there are any other quantitative measures of student outcomes that it should consider (for example that “start to success” it was privately floating a few weeks back);

- To get around small sample sizes we’ll get to see both five year aggregate figures as well as one year figures for all providers;

- And “modular provision” will be subject to some more… thought and consultation.

Tabulation saves the nation

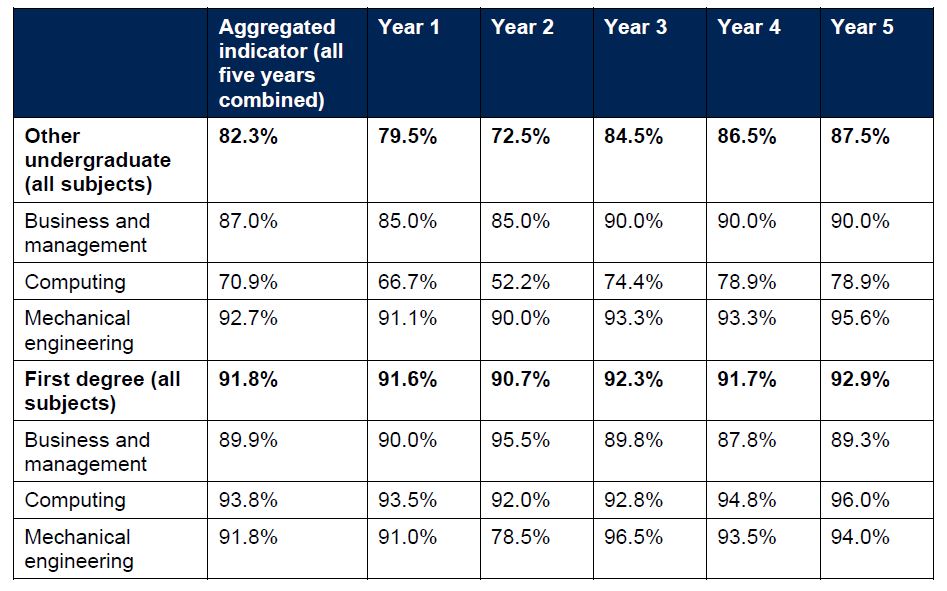

For the avoidance of doubt, what we’ll therefore see for every provider in every subject is the overall performance against each of the three metrics, broken down into both full-time and part-time modes, and separately within each mode for level of study for each of other undergraduate, first degree, undergraduate with postgraduate elements, PGCE, postgraduate taught Masters, other postgraduate and postgraduate research – so a table for a provider might look something like this:

Frustratingly, what we won’t get to see is the figures for franchise provision separately – but controversially for some, we will see the figures for validated provision under the totals of the validator, which is going to cause a fair few partnership offices to need a sit down this morning.

OfS says that’s because it wants a “universal” view of all the students a provider teaches, registers and all for whom it is the awarding body – but that’ll be frustrating for those who suspect that the outcomes for some students in validated provision are opaquely poor in comparison to those of the validating mothership.

What’s that you say? How does all this work for new providers without a track record? This is a real issue – for example, OfS notes that it can be “difficult” for a provider to demonstrate that students are provided with the support they need to succeed (as required by condition B2) when it has… no students to provide the support to. The proposal is that these providers are assessed on the basis of the adequacy of their plans to meet the requirements when they do deliver higher education courses, and an OfS judgment of the likelihood that such plans will be implemented effectively in practice. How that judgement will work isn’t clear.

Further indications

The baseline metrics will not be the only tool in the OfS’ quality arsenal – there will also be contextual information on each provider alongside a series of indicators.

The “contextual information” will be usable by a provider as a way of explaining or excusing poor performance – OfS says that if a provider’s performance was below one or more numerical baselines, this could potentially be judged to be acceptable if there were contextual or other relevant factors that accounted for such performance.

The latter “indicators” are a way of OfS peering into the future to get advance warning of stuff that might be about to go wrong. Some examples? Well, everything from patterns in applications and acceptances, to student surveys like – to take an example entirely at random – several identified questions in the National Student Survey, to numbers of internal or referred to the OIAHE student complaints, right through to poor performance (the “lowest rating”) in whatever TEF becomes. And, of course, sudden shifts in the numbers in any of the main performance indicators, or other bits of the regulatory framework.

There isn’t an exhaustive list – clearly any information from or about a provider could be an indicator.

We suspect that the recently trialled “start to success” compound metric could absolutely play a part as one of these indicators – OfS has quietly been developing a whole bank of measures that could play a part alongside existing key performance indicators.

Another senseless war

So what happens if one of the indicators is flashing red? In that case there’s going to be some further information gathered – in a curious phrase that is often repeated OfS may do this themselves, or “may ask the designated quality body, or another appropriate body”. There’s an odd precision to the plan that “we would not ask the designated quality body to gather evidence in relation to a provider’s compliance with a condition relating to student outcomes.”

One of the least edifying things to come out of the post-2017 regulatory system is the utterly pointless battle that OfS appears to believe it is fighting with the QAA – its ministerially appointed Designated Quality Body. The Quality and Standards Review for registered providers in England, designed by the QAA under close direction from OfS, is specifically focused on measures around student outcomes and baseline requirements.

Providers are also required to support all students to achieve successful academic and professional outcomes as a part of the QAA Quality Code. OfS is also determined – for no good reason that we can see – to remove any vestiges of the Quality Code from the regulatory framework, even though by their own admission “the regulatory requirements expressed in the regulatory framework would continue to broadly cover the issues expressed in the expectations and core practices of the Quality Code”.

The Quality Code, lest we forget, is a short and commendably clear set of core and common practices developed by the sector (under the auspices of the UKSCQA) to underpin the many distinct approaches to quality assurance in the UK. Unlike – say – TEF, it is not an approach that is widely criticised by the sector, and manages to walk a number of different tightropes to keep an enormous number of stakeholders happy.

There is literally no reason for OfS to shift it out of the regulatory framework – the wafer thin justification here is on provider understanding of burden – odd given that it is one of the most uncontroversial and straightforward parts of the regulatory framework. It seems like a bit of an own goal – especially as it allows Universities UK to own the more practical end of working with provider-based course review process that will actually get rid of poor-quality courses and impress ministers, while OfS appears to be stuck on identifying more sticks to beat the sector with.

Those sticks in full

And once it has that extra data? “Enhanced monitoring” is off the menu, so the OfS response to concerns about dips below baselines range between the traditional stern letter and the full panoply of HERA enabled fines and de-registration measures. The missing middle also means that OfS no longer has any ability to “impose enhanced monitoring requirements designed to prevent possible future breaches.”

This, to us, is important. Surely, the point of regulation built around the needs of the student is to prevent said student from having a poor quality experience. If your dashboard is telling you this is becoming a real risk, a regulator needs to step in now, rather than wait until the outcomes metrics fall below the baselines and actual students are disadvantaged. OfS’ argument is that now all the providers are on the register and have satisfied the B conditions, there is less risk – an assumption that would feel dubious even without a massive global pandemic and subsequent economic chaos as a live issue.

In summary

England’s regulatory system is in need of an overhaul – and the re-introduction of registration requirements as we hopefully reemerge from the current emergency is the perfect time to do it. DfE has tossed ideas around low quality courses and bureaucratic burden into the pot – but there should be other ideas in there too. There is a need, for example, to ensure that a new system properly meets the information needs of current students and applicants. And there is also a need to encourage the expansion of high quality provision if there is any hope that the aspirations of the next generation of prospective students will be met.

But HERA and OfS were both imagined in a different political context, and these are proposals and powers that respond to a different world, where we’re keen to “save” disadvantaged students from being “mis-sold” into courses that don’t provide the outcomes that sub-degree higher technical courses or FE options might provide.

All of that means that the measures described within the consultation would radically increase the powers that the regulator (and by extension, ministers) would have to intervene in issues around the academic offer, and the recruitment of students, that would previously have been considered as being subject to institutional autonomy.

Far from facilitating the managed expansion of the sector to meet applicant needs – as the regulatory framework was originally designed to do – this consultation presents a toolset to allow the careful setting of baselines and benchmarks to play a part in pruning the sector to a political design. What we don’t know is whether 72 pages and 28,000 words will turn out to be a bit too complex and clever for its own good – especially when ministers could just reintroduce student number controls and be done with it.

We need to remember that learning for learning’s sake is a rewarding objective. Many people do a degree because they are interested in a subject area and not because they want a career in that field. Indeed the skills from such a degree are transferable to the world of work, with English and History graduates in high demand due to their analytical skills. But can these skills be quantified?

We live in dangerous times if degrees end up becoming completely comodified by capitalism.

You can forget History Graduates being in demand, unless they are A. personally well connected and B. Studied at the ‘right’ University. As my son and his friends have discovered, one who wanted to do a Masters and/or PhD has been refused by all the Russell Group Universities he’s applied to with a First from Winchester. My son’s 2:1 has meant staying on at Sainsbury’s, a job he started to fund himself so as to keep his University debt down, stacking shelves, he applied to the Navy to become a ‘Graduate entrant’ officer but was turned down as he’d not… Read more »

Quality means minimum three C at A-level (or similar) for admittance to a university course. Simple!

You can only stand back and admire the twists this government gets itself into. Since 2011 when govt realised that average fees were coming in way higher than the modelled affordable level of £7.5k, virtually all policy has been to encourage new competition from outside the established sector in the hope that market competition would work to lower average fees. This culminated in HERA 2017, which finally legislated for easier access to DAP and UT on a level playing field register of providers. The 2016 white paper actually suggested that – by allowing some providers to fail and exit the… Read more »

The burden of this article is that the proposed changes are likely to make things worse. There is never a shortage of arguments that the status quo is better than any proposed alternative. This is particularly so in the tradition-encumbered world of higher education. It is about time that Wonkhe (and others) came out with clear and feasible changes that were not in the self-serving interests of an academic culture that focuses on producing publications that no ones reads, in pursuit of status in an in-group that looks only at itself. The reality is that the great expansion of higher… Read more »