The publication of an Office for Students quality assessment report for business and management courses at the University of East London brings the total of published subject-focused reports up to three, out of ten in train.

The University of East London (UEL) report does not identify any concerns on the academic experience offered to students (B1); on resources, support, or student engagement (B2); or on assessment and awards (B4). In this respect it is similar to the earlier review at London South Bank University (LSBU).

The other extant report, at the University of Bolton, identified four concerns relating to condition B2: on the availability of staff resources to support student learning, support for avoiding academic misconduct, the format of formative feedback, and progression for former foundation year students.

Importantly, we do not yet have any regulatory judgements on these investigations from OfS – these reports simply represent the conclusions of the assessment team.

But, more importantly, we’ve never had any detail as to how these things work in practice. If you look at quality assurance processes in other higher education systems we get the practicalities (stuff like how long it will last, what they’ll be assessing you against, what stuff they want to see) in great detail – this serves to reassure those involved about what is happening (including when to expect stuff to happen), and to draw constraints around what the quality assurance body can and can’t do.

So for the OfS quality processes, it’s more a matter of piecing the clues together from the reports that come out – which is what you’ll find in the rest of this piece.

The process

One of the main criticisms of the various OfS investigations into provision is that providers have never explicitly been told how these things work or what those under investigation should expect. Because there are now three reports we can start to piece these together for the subject area investigations – which from the looks of it, all focus on registration conditions B1, B2, and B4.

We don’t – yet – have any outputs from the ten investigations (possibly plus a further six, the board paper is old and unclear) into student outcomes (B3), from the three investigations into the credibility of awards (we assume B5?), or from the investigation into free speech at the University of Sussex that started nearly two years ago.

Areas of concern for further investigation are chosen annually by the Office for Students – in these three cases this happened in May 2022. Decisions are made based on outcome data (likely to be B3 data on continuation, completion, and progression), student experience data (likely the 2022 National Student Survey results available to the regulator in May and published in July), and any notifications made.

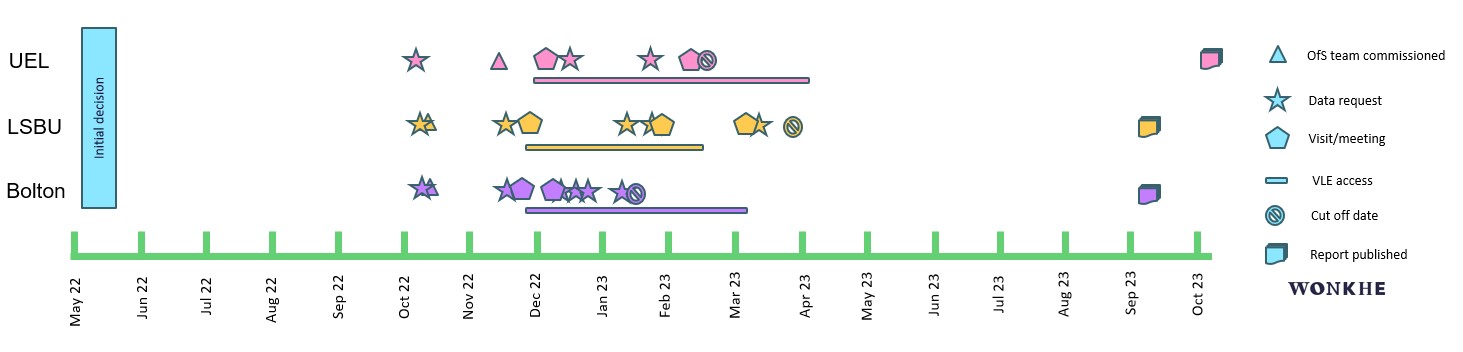

After these decisions are made, an assessment team is commissioned. In each of the three examples, this was made up of three academic experts plus a member of OfS staff – though we don’t know about any overlap (it would be useful to ensure commonality of approach). There appears to be quite a long gap between the decision and the commission – for Bolton and LSBU the team came together on 19 October, whereas for UEL this was on 3 November.

At a similar time a request for initial data is made to the institution in question – this happened on 18 October for Bolton, 19 October for LSBU, and 13 October for UEL. This is by no means the end of data requests – UEL got an extra two (December and January), LSBU an extra four (November, two in January, and March. Bolton somehow had to deal with five additional requests (November, three in December, January) and also made an additional submission. It’s not made explicit, but it seems likely these additional requests are made on the basis of interim findings.

Getting stuck in

The “boots on the ground” component constitutes two visits to the sites in question, plus a period of sustained access to the institutional virtual learning environment. The pattern seems to be an initial visit, plus a follow-up later in the assessment process.

- For UEL: visits on 8 December and 13 February (plus online meetings on 14 February), access to the VLE from 2 December to 7 April

- For Bolton: visits on 22 November and 12/13 December, access to the VLE from 22 November to 3 March

- For LSBU: Visits on 29 November, 31 January, and 10 March, access to the VLE from 23 November to 17 February

The differing number and type of visits and lengths of time spent experiencing the VLE suggests that the format of these investigations is variable, most likely based on emerging findings.

There is always a decision made by the assessment team on “lines of enquiry”, seemingly made towards the start of the process based on initial information. For LSBU and Bolton this followed the experiences of the majority of students in the subject area – in both cases larger on campus undergraduate courses. At UEL a decision was made to focus on a BA (Hons) in Tourism Management, based on module marks and student views of the course.

The detailed assessments following these decisions are supported by access to a range of documentation, and interviews and discussions with staff and students. These can include but are not limited to programme handbooks (and more general information provided to students), module attainment data, course and module specifications, and student complaints and their outcomes. At UEL, assessors also asked to see course validation and evaluation data and module validation data – whereas at Bolton the team got stuck into withdrawal and attendance data and external examiner reports. At LSBU assessors also observed teaching on two modules.

The Bolton example, as the only one so far to feature concerns, goes into a lot more detail and presents a lot more data than the other two examples. It is fair to see this as the provision of detailed evidence that would underpin a regulatory decision.

A common feature of these reports is a cut-off date, beyond which information made available will not be used in developing the assessment report. For UEL this was 14 February, for Bolton 6 January, and for LSBU 28 March. Reports themselves also take differing times to emerge – at UEL and Bolton this was after around eight months, and at LSBU after just five and a half months.

Here’s how it looks:

Regulatory action

We don’t yet know the timescale or the process for deciding on regulatory action (though we do know OfS will get advice from its Quality Assessment Committee (QAC) on this). It feels likely that there will be no action taken at LSBU or UEL – in each case the assessment team found no concerns.

At Bolton each of four concerns could see action – but it is difficult to imagine what action could be taken that would improve the student experience. The fashionable options of a fine or a recruitment freeze would make it harder for the university to fix the staffing issues that appear to underlie each concern: more staff would need Bolton to have more money, not less – so taking money away (either directly or indirectly) feels like a surefire way to make the student experience worse.

It would also be very likely that any provider facing regulatory consequences would challenge the decisions made based on the evidence presented in the assessment report. This currently feels very messy as ostensibly the same body is both judge and prosecution – but any appeal could likely focus on the process followed for each investigation, which appear even based on three data points to be arbitrary and inconsistent.

A further thread worth pulling is the time delay between OfS data and what is happening on the ground. In each case the OfS assessors found that measures had already been put in place to address the concerns in question – often some time previously. Any well run university would already be aware of irregularities in data and would put in place mitigation measures as soon as issues became apparent – a better understanding of internal provider quality assurance mechanisms would have helped the regulator here.

David, reading your article made me think of European Standards and Guideline for Quality Assurance Part 2, in particular standard 2.5, criteria for outcomes, “Any outcomes or judgements made as the result of external quality assurance should be based on

explicit and published criteria that are applied consistently, irrespective of whether the process leads to a formal decision.” Are there any? Also, do we know what the appeals system is? Standard 2.7 Complaints and Appeals, “Complaints and appeals processes should be clearly defined as part of the design of external quality assurance processes and communicated to the institutions.” I can’t see anything on the OfS website.

Excellent point. Whilst it is easy to criticise the ESG for the generic nature of their content, nevertheless they provide clear indication of the core and quite irrefutable principles for QA in HE in the EHEA.

The OfS is an affiliate member of the European Association for Quality Assurance (ENQA). It can only become a full member of this representative body if it undergoes a review by ENQA against the ESG. Almost all other European bodies with responsibility for QA have been reviewed against the ESG. Most will take very swift action to rectify any matters raised in the report as recommendations.