This week the government has repeatedly stressed that it is looking to encourage “open intellectual debate” and counter what it calls the “chilling effect of censorship on campus”.

But before it introduces new laws, it should look properly at some existing ones. In January 2021, it announced that it had appointed William Shawcross, the former head of the Charity Commission, to chair its much-delayed review of the Prevent Duty.

This development confirmed beyond a reasonable doubt that the Government’s review is a sham – aimed at whitewashing a fundamentally flawed strategy and strengthening its crackdown on civil liberties. Dozens of leading human rights organisations and hundreds of Muslim community groups have joined a growing boycott of the review. Universities should follow suit.

Prevent is the flagship policy of the Government’s counter-terrorism strategy, known as CONTEST. Launched in 2003 and expanded into a legal duty in 2015, Prevent requires public sector organisations such as universities to monitor people and report any suspected signs of “radicalisation,” with the stated aim of “safeguard[ing] vulnerable people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism.”

In other words, it is concerned with policing “pre-criminality” and is premised on the bogus claim that certain “risk factors” predispose specific types of individuals to future participation in violence, such as a “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values.”

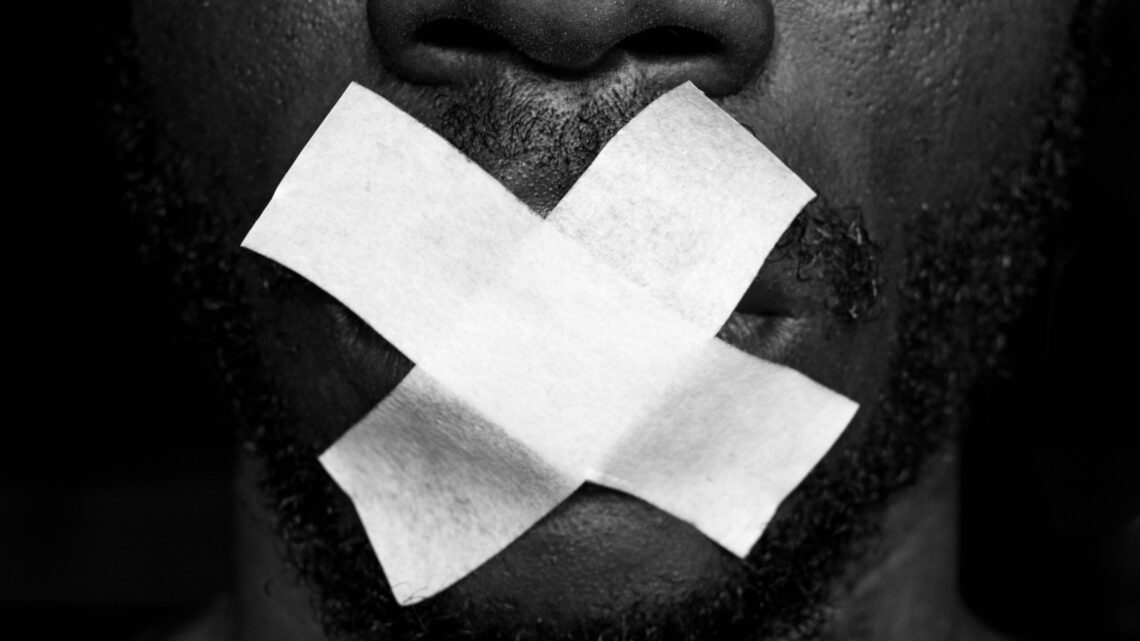

Critics warned that the policy’s vague, open-ended definition of key terms such as “British values” and conscription of public sector workers into the frontlines of state surveillance would institutionalise Islamophobia by stigmatising Muslims as suspects and silence open discussion, debate, and dissent.

Chill out

It should come as no surprise then, that Prevent’s “chilling effect” has stifled free speech and harmed Muslim students in particular. In 2017/18, 44% of cases referred to Prevent were for concerns related to “Islamist extremism” (meaning that Muslims were 40 times more likely than the rest of the population to be reported), and less than 1 in 10 required any further action (demonstrating that the “risk factors” used by Prevent are not reliable predictors of future participation in violence).

Prevent’s “chilling effect” has created a culture of suspicion and silence. A 2017/18 survey of Muslim students carried out by the NUS found that 1 in 3 felt negatively affected by Prevent, and among those, close to half felt they were not able to express their views due to fear of being reported. 34% of Muslim respondents to a 2018 survey conducted by Cambridge SU on students’ perceptions of Prevent felt that it “very much” had an impact on their current studies, compared to 13% of students overall. Varsity, our student newspaper, found that Prevent’s roll-out in Cambridge’s Colleges had been characterised by considerable discrepancies and a lack of transparency and accountability, leading to many Muslim students “censoring” themselves or limiting their visibility in student life.

While universities continue to maintain they can balance their legal duties to follow Prevent with their moral duty to safeguard basic civil liberties, government-mandated surveillance has only deepened, with Prevent being embedded in student support services. In November 2018, the Government revised its Prevent guidelines to promote greater coordination across the public sector — and as part of this, universities and colleges were even required to report on the number of students accessing support services such as counselling, regardless of whether these cases were Prevent-related.

Review time

The mounting pile of evidence led the Government to concede to a review of the policy in January 2019. From the outset, the review was mired in controversy. The Government’s first choice of chair, Lord Carlile, was forced to step down in December 2019 after a lawsuit challenged his objectivity and suitability for the post, given past comments he had made about his “strong support” for Prevent.

Shawcross’s objectivity is equally questionable. As a director of the Henry Jackson Society, a neo-con foreign policy thinktank, Shawcross described Islam as “one of the greatest, most terrifying problems of our future,” and as chair of the Charity Commission, he was accused of launching a crackdown on Muslim charities. Furthermore, the review’s terms of reference have been narrowed to limit its remit and restrict the range of evidence and expertise which will be consulted.

This is the context in which many groups have decided to boycott the Government’s sham review of Prevent. Shawcross’s appointment has confirmed, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the Government has no interest in conducting an objective review of Prevent, or in engaging meaningfully with communities that have been harmed by it.

It is now more clear than ever that the review is nothing more than a stunt aimed at whitewashing Prevent and rubber-stamping a fundamentally flawed strategy which threatens civil liberties. Crucially, this latest appointment is not an isolated incident — it represents the the wider weaponisation of public institutions to neutralise the growth of mass movements for social justice through sham “consultations” that serve to rubber-stamp damaging policies, as exemplified by the recent report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, which blamed BME communities for their own marginalisation and was labelled by the UN as a “distortion and falsification” of facts aimed at “normalis[ing] white supremacy.”

Of course, it has also coincided with the furor surrounding the Police, Crime, Sentencing, and Courts Bill. We need to see this review as part of a wider crackdown on movements that dare to challenge the status quo and demand a more fair and just society.

Reform is not possible

While the Government may tout the growing proportion of cases reported to Prevent that relate to right-wing extremism as evidence that the policy is “not racist,” we should be steadfast in our view that Prevent cannot be reformed. Going forward, the only sensible option left is to demand nothing less than the abolition of Prevent — a view which is now shared by a growing consensus of human rights groups and experts, ranging from the UN Special Rapporteur on racism in the UK to even the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Max Hill Q.C.

Rather than criminalising entire communities and fostering suspicion of each other, we need to build solidarity on the basis of a shared vision of a world without oppression. This means rejecting the government’s sham review, which will only further entrench Prevent and strengthen the policy. Dozens of leading human rights organisations and Muslim community groups are doing just that, boycotting the review to protest the government’s latest stunt and demand an independent review process which centres the voices of those most harmed by Prevent and is supported by credible expertise and robust evidence.

We are calling on universities to back up words with actions and support the boycott. By backing the boycott, universities can send a clear message to the government – the whitewashing of Prevent’s harms will not be tolerated, and, moreover, none of us are safe until all of us are safe.

Cambridge SU has launched a Preventing Prevent toolkit.