Are students clustering out locals in the battle for housing?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

If there’s a totally uncapped demand-led system where subsidies are insufficient to keep smaller campuses and student towns/cities going, the clustering assumption in that kind of raw marketisation is that it would put pressure on housing stock, and therefore rents.

Pressure on rents both for students away from home, and local citizens – many of whom are also students who also (or their families) rent.

That ought to be something that the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (or wherever it’s called this week) is interested in or concerned with.

We don’t know precisely if the theory is borne out in reality – the nation’s data on rent levels is useless – but we can get relatively close via council tax data.

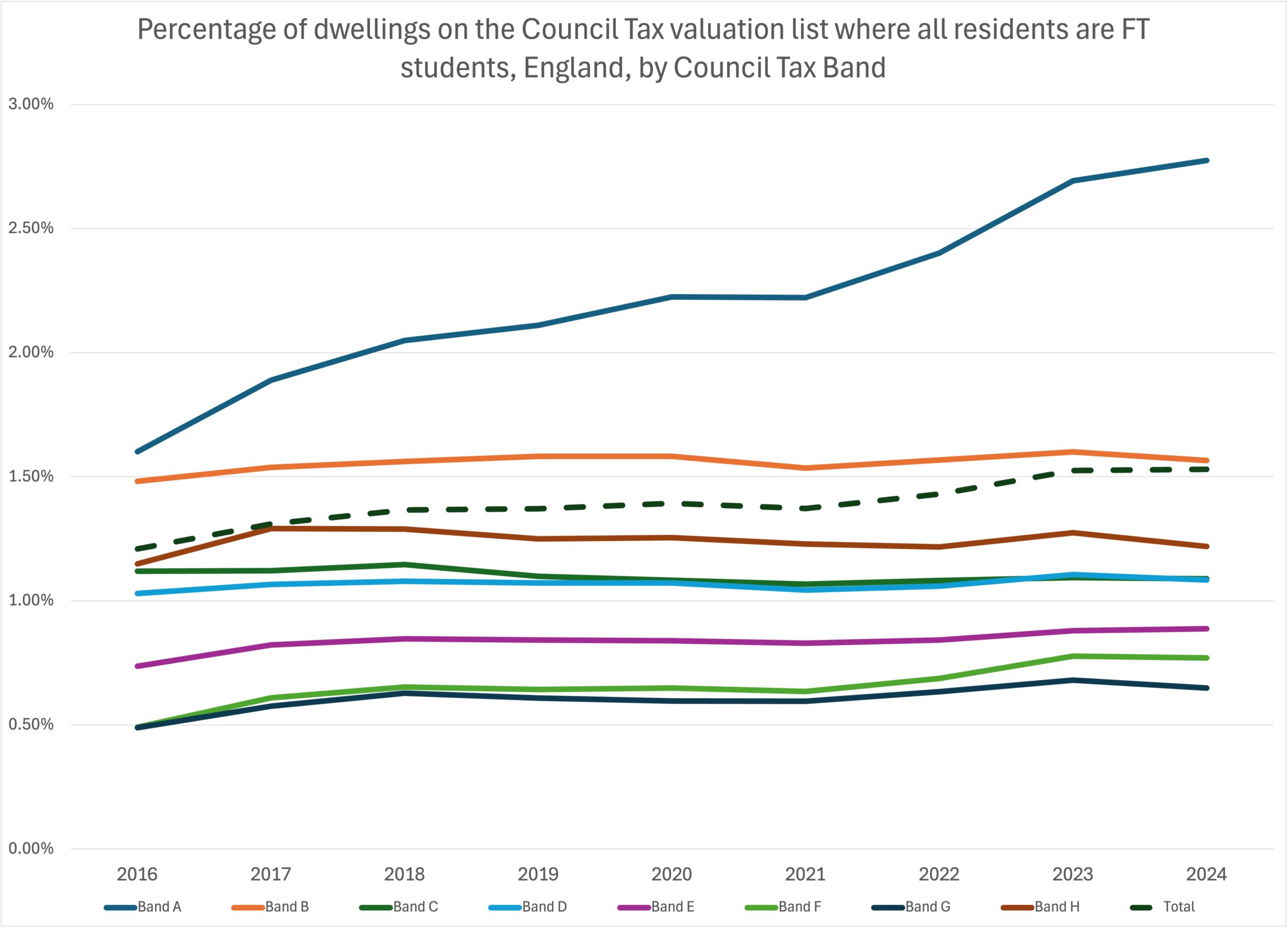

Here’s the percentage of dwellings on the Council Tax valuation list (for England) where all the residents are full-time students:

The dotted line is the overall percentage of dwellings, and you can also see the percentages by Council Tax Band.

To listen to the landlord lobby, you’d think that student landlords have been staging a mass exodus. There’s actually been a fairly steady/gentle increase as student numbers have grown – save for by Band, where the cheapest properties are those where students are clustering in general.

None of this tells us about proper Purpose Built student accommodation, and nor does it tell us how many students are in each property – but you can bet that as properties become student properties, they are being flipped in such a way as to house more people than previously.

That’s England in general though. If you have a drill into specific local authorities, things get much more interesting.

In Exeter – the subject of this bog standard town/gown studentification piece in the Telegraph – 16 per cent of Band A properties were student ones in 2016, rising to 26 per cent in 2024. Overall student properties in the city have gone from 7.7 per cent of the stock to 11.2 per cent in the period.

Bristol’s famously tight (and expensive) student market is similar. There Band A properties went from 3.6 per cent student to 8.8 per cent student over the 8 years. There are only 17k more properties in Bristol over the period – and students nabbed 27 per cent of them.

In Liverpool, rent increases have also been high in a city whose student numbers have grown – even though extensive “proper” PBSA has cushioned things. There there are 22k more properties than eight years ago, and 24 per cent of them are student properties. Its Band A stock has also seen the percentage that are student double.

Or take Durham – where 1.9 per cent of Band B properties used to be student, and now it’s 6.3 per cent. There’s only 15k more properties in Durham now when compared to 2016 – and students have taken up 15 per cent of them.

Contrast all of that with Arun, the home of the Bognor campus of Chichester University, which has neither been enjoying the stellar student numbers growth of some of our larger cities nor rocketing rent. There student properties have gone from 0.24 per cent to 0.29 per cent, with students making up just 1 per cent of the Band A stock.

The point isn’t that we should ignore student choice over where to study, and nor that we should ignore the economic benefits of student clustering to cities like Exeter, Bristol or Liverpool.

The point is that those upsides have to be balanced with the downsides of the health (and rent levels) of the places where students cluster into in a completely demand-led system.

Without housebuilding (or affordable PBSA development) to match student numbers growth, making it so expensive as to ruin the student experience and make it much harder to work somewhere for anyone in their 20s and 30s doesn’t feel like it’s in their interests.

And the inevitable other end of the see-saw – robbing other places of students because their subject area, campus or even provider is no longer viable – doesn’t feel like it’s in their interests either.

What it does do is increase the wealth of property owners – wealth we don’t tend to tax, and which squeals when anyone tries. And it’s wealth being transferred into bank accounts now off the back of a state-backed delayed contribution scheme. Social mobility in those circumstances becomes a very hard hill to climb.

Maybe the upsides of student choice outweigh it all. Maybe not. As I say, the point is that student numbers clustering involves trade-offs in other government departments, and for other citizens. As a country, we desperately need to be looking at those trade-offs in the round.

Come to the University city where I am and find out just how hated students, and their HMO (House of Maximum Occupation) slum landlords, are, because the price pressure has put homes out of reach for local people, to buy or rent. Meanwhile the University continues to ignore this effect on the local population. That’s without drunk s-too-dense using their front gardens and even door steps as toilets …