Let’s take an imaginary leap to the end of the decade and look back from that vantage point. The odds are we will still be debating how to measure the value of teaching, what it is worth, and what it costs.

Debate will be rumbling on about the legitimacy and limitations of the Teaching Excellence Framework, its methodology, and the difference between teaching quality and outcomes. Yet, there will be growing interest in “splits” – the demographic breakdown in the TEF assessment – and acknowledgement that university admission does not magically end the effects of social disadvantage.

However, whether they were delighted or disgruntled by the 2017 TEF results, what did universities and colleges do next? What, if any, practical steps were taken improve on a silver or bronze ranking, or consolidate gold? What were the lessons of the 2017 exercise?

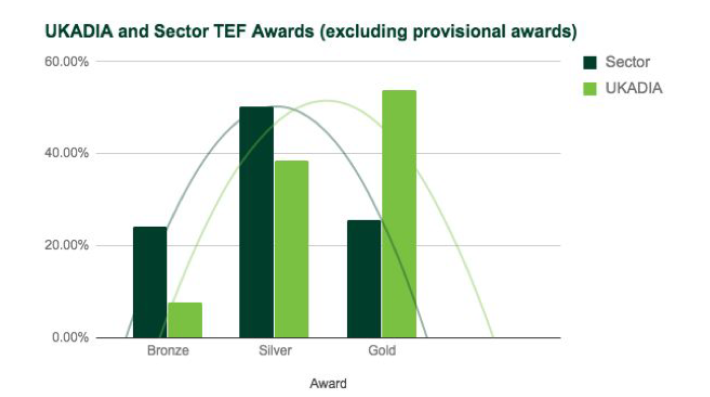

For the 13 specialist institutions that comprise the United Kingdom Arts and Design Institutions Association (UKADIA), common themes echo through the TEF Panel’s 2017 conclusions. Seven were awarded a TEF gold ranking, five silver, and one bronze.

Source: GuildHE

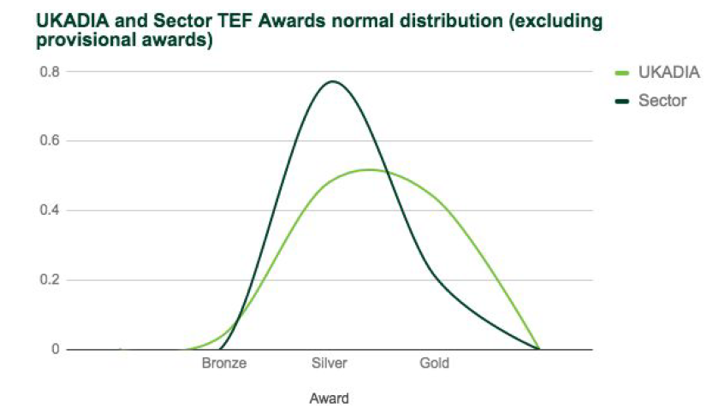

Analysis by GuildHE shows that the normal distribution of TEF rankings for UKADIA institutions – albeit a small sample – compared favourably to the sector as a whole.

Source: GuildHE

Drill deeper and you will find that eight institutions received single or double positive flags for graduate outcomes, whether highly-skilled employment or further study. And read the TEF Panel’s qualitative assessment and you will see evidence of each institution trying to align teaching and course design to industry practice and requirements.

Employer collaboration

Let’s take an example. The TEF Panel saw gold in the teaching at Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts, with “very high proportions” of students continuing their studies or moving to highly-skilled employment. Notably, the TEF Panel found “a rigorous approach for ensuring that students attain the skills most highly valued by the creative industries” including “an exemplary simulated employment environment in which masterclasses, mock auditions, placements and public performances ensure students are frequently and consistently stretched to achieve highly.”

In tandem with investment in high-quality technology and materials, they found a “strategic use of teacher-practitioners to frequently engage students with developments from the forefront of scholarship and professional practice, including collaborative work between students and professionals on projects throughout programmes.” The TEF Panel’s verdict on my own institution, Norwich University of the Arts (NUA), drew similar conclusions.

Course design and assessment provide “outstanding levels of stretch for students through encouraging experimentation, creative risk taking and team-working skills that are most highly valued by employers.” The investment in “high quality industry-standard physical and digital resources” is aligned with “a learning environment that is enriched by collaborative working, with staff who are professional practitioners in their own right, alongside frequent sessions provided by visiting lecturers and industry professionals.”

So what do we learn from this? Lesson one: invite the outside in. Not as guests, but active, ongoing participants – and from the moment a course is designed rather than its delivery.

Retention

UKADIA institutions also performed strongly on student retention.

According the GuideHE’s analysis, six of the 13 member universities and colleges were given single or double positive flags for retention of full-time students. Two UKADIA institutions received positive flags for part-time student retention. None of UKADIA’s member institutions received a negative flag.

The TEF Panel described “exemplary levels of student engagement and commitment to learning” at Falmouth University, for example. These standards reflected, in part, course design and assessment, and “personalised learning which is supported by a personal tutor system, support for different learning approaches, individual timetabling and a data-driven approach to monitoring contact and teaching patterns.”

So lesson two: play the numbers. Ensure a personalised approach to learning allied with – and informed by – data analysis can benefit students, staff and management.

Engagement

Similarly, at the Arts University Bournemouth, the TEF Panel remarked on “high quality teaching which provides stimulation and challenge with small classes and high levels of tutor contact” and “students’ independence … developed through the negotiation of assessments, project work and live briefs.”

At NUA, we believe that the seeds of student retention are sown at the application stage. All prospective students are interviewed by portfolio. It is their first opportunity to share their creative practice at a higher level – and to see us at work. New students are set summer projects and, on arrival, participate in a common project during their first week. This culminates in a university-wide exhibition of all Year One coursework. The aim is to embed peer review and interdisciplinary awareness from the start of their study – a demonstration of the ways that creative specialists work across teams. That gives us lesson three: start early. Student engagement with learning begins before entrants enrol.

Broadly, the TEF Panel’s conclusions about UKADIA institutions chime with the findings of the 2017 Student Academic Experience Survey conducted by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) and the Higher Education Academy (HEA). The survey found that specialist institutions performed better than average when students were asked to rate their university as either “good” or “very good” value for money. The key differences between specialist institutions and other universities were identified as the time committed to teaching, face-to-face feedback, and ongoing support from academic staff.

Yet, returning to our end of the decade vantage point, UKADIA institutions face other pressures. Chiefly, you cannot teach who you cannot recruit. The effective downgrading of creative subjects from the core subjects of the English Baccalaureate will affect pupil, parent and teacher perspectives on the value of art and design, for example. By the end of the decade, the effects of those negative perceptions of the value of creative subjects in secondary education will be felt in higher education.

Final lesson: however golden this year’s TEF ranking, no institution can rest on its laurels.

I’m unclear why GuildHE would apply a normal distribution to UKADIA’s distribution that is clearly not normal. Forcing the data to fit an improper statistical fit was inappropriate. The differences between UKADIA and Sector are clear enough.