Over the past year both our university and students’ union have each been developing new strategic plans. Being entities in their own right, each body has followed their own processes, consulted with their own stakeholders and produced their own strategies and action plans.

Strategic planning and development activity has largely taken place independently, has been ‘signed off’ separately at the relevant governance level (Board of Governors for the university and Board of Trustees for the students’ union), has been articulated through separate and distinctive documentation and will be promoted to different interest groups.

Independent but interdependent

But something feels just not quite right about the whole process. Although independently governed entities, in truth the university and students’ union are interdependent in their day-to-day operations. For example- the university depends on the students’ union to manage the course representative system and other mechanisms for gathering student feedback, and the students’ union depends on the university to respond to and act upon that feedback (to close the feedback loop) to make tangible improvements to the student experience that students recognise.

The students’ union depends on the university for its annual financial block grant, its premises and ‘back office’ support and guidance in relation to financial and HR issues; and the university depends on the students’ union to demonstrate good financial management and governance, to ensure appropriate use of premises and to deploy high standards of service to students in order to safeguard and ideally enhance the university’s reputation.

There are many other examples of how the university and students’ union rely on each other; in fact the mutually reliant relationship starts with the fact that if universities did not recruit students, then there would not be a need for a students’ union.

A question of scale?

Given this experience- which is not uncommon- an obvious conclusion would be to create a shared approach to developing strategy for the two entities. But this iis not necessarily the case for a multitude of reasons. Universities are, typically, looking ahead on a 5 – 10 year basis at least and will have capital developments or research projects where there are timescales of decades- and may well be operating on an international basis. Students’ union differences in scale (as well as breadth of operation) require different planning assumptions and ways of thinking about what can and will be achieved and deliverable, and are often necessarily and rightly shorter term and keen to be responsive in their thinking.

Similarly the resources available to be deployed are very different and different approaches can be required for a strategy for an organisation with a turnover of over £100m to one with £2m. The ‘audiences’ too are different with varied expectations and requirements. Students’ unions need strategies for members with time horizons for deliverables that at most are 3-4 years, and where results will need to be seen within that- and key elected officers are generally transient figures. This is not seeking to suggest one is better or worse than another; they are different. With these differences in mind, separate strategy development make strategic sense.

And yet there remains a nagging sense that these are two organisations with one major and shared group of stakeholders and a shared purpose of providing the best experience for this group, within usually the same locations. A key deliverable for both is always the quality of the student experience in the current year and next and this of course is then often reflected in NSS results and used in league tables. So a common approach to developing their strategies should make sense.

Agility of thinking

And whilst there are a range of differences, the current separation may just be in itself perpetuating differences that are both unnecessary and unhelpful- perhaps the best from each approach could be brought together. Students’ unions can bring a freshness and agility of thinking, clarity of language and a real diversity and inclusivity in the development and feedback stages, as well as an approach less fettered by overthinking the perceived need that their strategy should try and meet the expectations of a group of stakeholders that can be too wide.

Recognising the value of developing a common approach is likely to require some changes and a ‘loosening’ of approach by universities but their experience in areas such as measuring and demonstrating performance and impact, as well as planning for the long term would bring its own value to the shared approach. In most areas of work (and life) there is little where collaborating does not bring additional value including tangible efficiencies: which of us would not want more of that? ‘Strategic Development’ can become somewhat self-important and we should recognise that at the end of the day it is about managing change- if the future was certain and nothing needed to be done different why would we need a strategy? As such one of the keys to successful change management is to be able to change what and how you do things, so maybe we need to move towards developing our own strategies but with a shared process and approach to strategy development.

So what is the way forward? How might we bring together strategy development for universities and students’ unions? One approach would be to zoom right out and find the point at which they are closest together; they do not run in parallel so there is a point to be found (much in the same way that both a mouse and a whale, obviously completely different, meet at their animal classification of ‘mammal’).

Getting closer

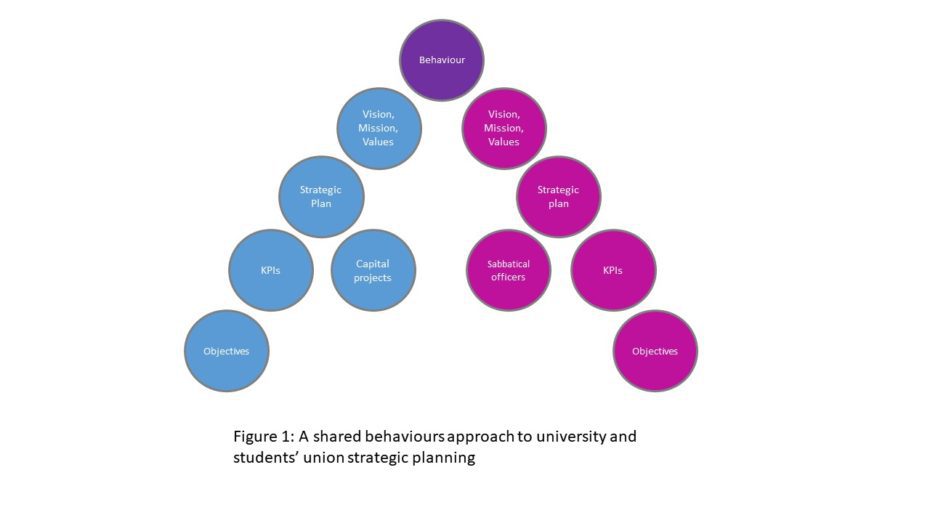

Figure 1 shows where universities and students’ unions do start to come closer together in relation to strategy. The detailed objectives they set might be completely different, but as we begin to progress up the pyramid, things become closer. It would be expected that something akin to ‘a positive student experience’ would fall in both strategic plans and that words synonymous to ‘student support’ would appear in each ‘vision, mission and values’. Therefore the top point of this pyramid should be behaviour- because the way in which our people and organisations behave, given the locality, type and status of the institution should be the same or at the least, very similar.

Beyond that the respective stakeholders, size and organisational rhythms will start to differ. Students’ Unions will want to find ways to incorporate the views of elected officers and new students to respond rapidly. Universities will want to take a long view to justify investment decisions and reflect the need to take time to change large scale culture and practice. But in truth both approaches should feed each other. If Universities can identify ways that their union’s agility can feed into annual operational planning decisions, and students’ unions can identify ways in which they can feed into and reflect long term decision making, both bodies will benefit.

Ultimately neither SUs nor universities are machines, and often don’t conform to codes and algorithms. Both are run and led by people. Because of this it ought to be possible for a university and its students’ union to come together to agree an overarching set of behavioural aspirations whilst still retaining their unique ways of working as we travel down the pyramid, with both at all stages delivering the absolute best experience it can for its students. After all, without them, neither of us would be here!

This piece relies on the assumption that student unions’ stakeholders = students. Unfortunately, university student populations are too large for this assumption to hold. Instead the stakeholders of an SU are those groups of student factions with sufficient incentive to organise. Typical symptoms are low electoral turnout, low NSS satisfaction scores, the “mandating” of elected sabbatical officers to vote or take positions that are dictated by the factions, and mismatch over time between the profile of elected officers and the student electorate. As the author is correct to point out, SUs have also developed financial dependency on central block grants from a university. There is in consequence already a form of collusion between the administration and the union but not one that is built around the interests of the whole student body. The block grant makes it possible for the SU to argue that all students are “covered” by its umbrella irrespective of whether particular sections (a department, a college in the case of a collegial university) seek to disaffiliate from the SU or its parent body the NUS.

Beneath the surface veneer of the blog post is a blueprint for monopoly: an administrative monopoly (sole campus provider of services) and a union monopoly seeking to entrench each other’s position. To return democracy and choice to the campus requires the opposite approach: decentralisation, subsidiarity, and the empowering of departmental boards that represent students and academics directly.