As Dani Payne notes elsewhere on the site, one of the major problems for universities in lobbying for funding is a lack of clarity on where the money goes, and a set of global (ish) figures that make the UK system very expensive.

Wherever else the UK’s Transparent Approach to Costing (TRAC) data does for Finance Directors, it apparently doesn’t achieve the T in its name for the public funders and/or loan financers of higher education – and so the default way to understand it all becomes the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s data.

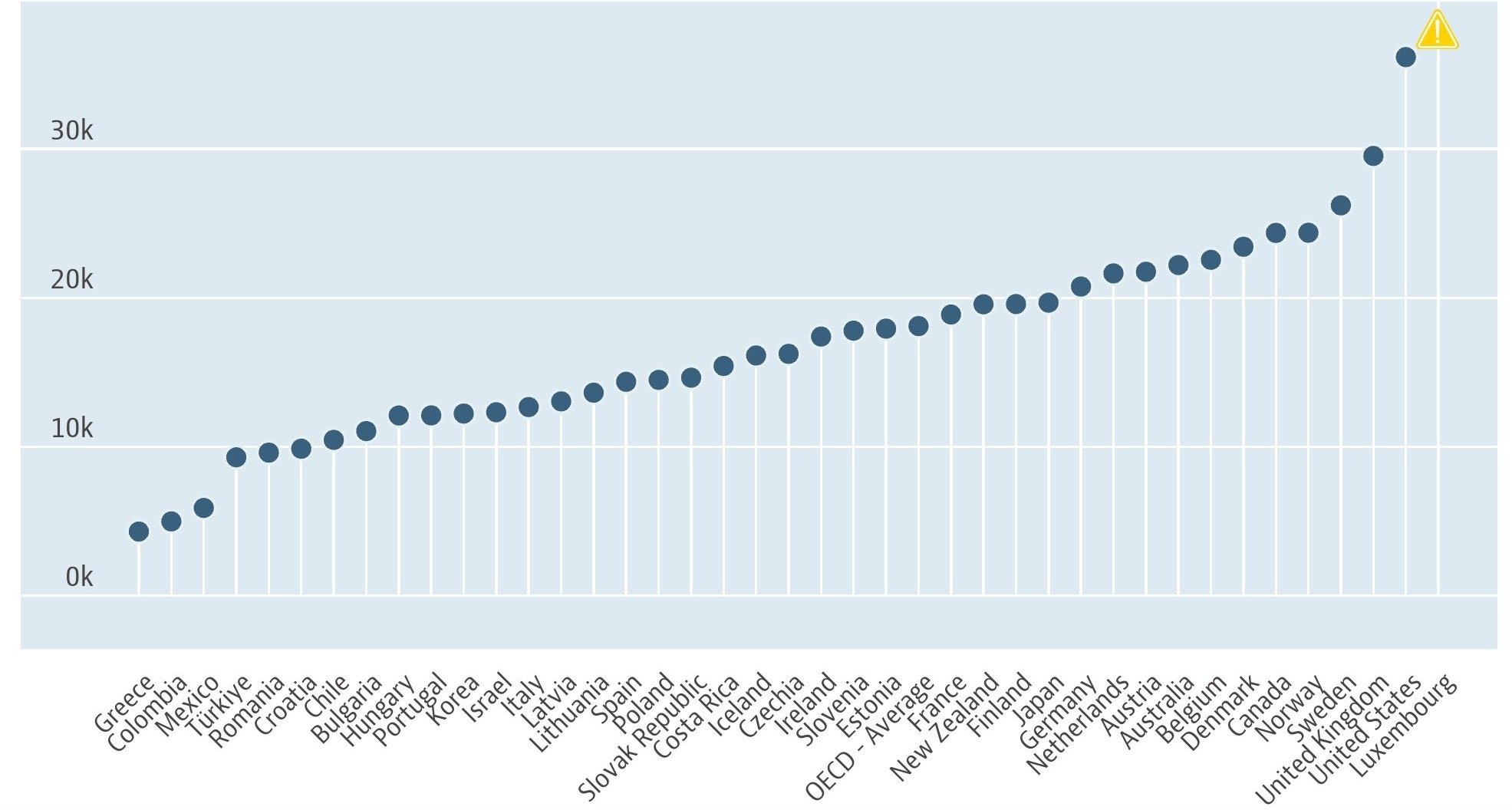

And the chart I’ve been repeatedly referred to by baffled officials right around the UK from that source is this one from the OECD’s annual Education at a Glance report:

That is supposed to be showing expenditure per head on tertiary institutions per student in US dollars in 2020. And on the face of it you can see why, in the absence of other explanations, officials might be briefing ministers that universities should be able to take a dose of spending restraint without completely destroying the UK’s competitiveness in higher education.

This matters – partly because there seems to be a pretty lazy assumption around that the reason the Westminster government won’t look at this is pre-election exhaustion/lethargy and a right-wing desire to shrink the sector.

Maybe that’s part of it, but it doesn’t explain an almost-identical attitude to similar issues in Wales and Scotland – unless you extend your hopium and copium to “well that’s all Westminster and the Barnett formula’s fault”.

Let’s imagine that this is all a bit more deliberate than universities just being low down the political pecking order. Whether governments and/or their regulators/funding councils are choosing between intervening to assist the sector in reforming operations, or choosing instead to deploy institutional autonomy/the market to force change, what they’re not choosing is to maintain the unit of resource at its current levels.

They might not be picking an obvious fight over that level needing to come down, but neither are universities picking a transparent fight over the need for the funding level to come up beyond arguing that “we lose money on every domestic student recruited” – which I hear is being met with “well you only make a loss because you find the revenue from elsewhere”. Isn’t revenue supposed to drive costs, not the other way around?

So what could be going on? My colleague David Kernohan would be the first to argue that the OECD’s comparison figures are for amusement purposes only – the definitional problems plus the data gathering against those definitions almost certainly render the figures unreliable.

But that surely can’t explain all of it. And so in the absence of more reliable comparisons, I’ve collected and summarised here as many of the cod-theories I’ve heard over the past year or so that seek to explain (away) the UK’s outlier status along with its bedfellows the United States and Luxembourg – the former of which appears to spend billions on sport, and the latter of which is a tiny tax haven – and so neither of which are especially helpful.

Yes but they pay (almost all of) it all back

One thing I’m regularly reminded of – or rather I’m regularly reminding others of – is that regardless of the amount spent per head, the Westminster government (and to a lesser degree nations governments) are recovering a lot of it through loan repayment terms – 72p in the pound for English undergraduates on Plan 5, according to the Department for Education the other day.

The problem with that argument is that the size of the government debt pile is, whether we like or or not, a public policy concern, the nature of the system in framing it all as debt is a concern for graduates and the public, and the sticker price does matter – especially if all concerned suspected that it all be done cheaper.

When DfE ministers say they’re holding down the maximum tuition fee to “ensure value for money”, wonks like me might bemoan that they’re hiding other changes that make HE more expensive over an average graduates’ lifetime, but it’s a reasonable bet that the line plays well.

We should have kept the polys

The conversion of what used to be a dual system of polytechnics and universities back in 1992 looked like the right thing to do then for all sorts of reasons – but I’ve often had it put to me that the “levelling up” of esteem intended did nothing of the sort, and in fact has just caused delivery homogeneity, mission drift and an unnecessary glut of research (which is often blamed for sucking money out of teaching) that has little impact.

Decent figures on comparative spends per head between the duality in the majority of countries that maintain such a split are exceptionally hard to come across, partly because while most countries do retain universities of applied science, research universities and a smattering of other providers, the actual categorisations are very different below the headlines.

And while higher level vocational/technical skills remain those in most demand in most systems, it’s also clear that other countries are having decent stabs at vocational esteem – if they’re doing so more efficiently, and pretty much nobody in Europe has copied our 1992 experiment, it’s hard to dismiss the detail in the critique out of hand.

It’s all those buildings and busyworkers

If I ask the question on Twitter/X “why is UK HE so comparatively expensive”, I do get two kneejerk responses fairly quickly – one that retreads the “shiny buildings” trope beloved of the HE sector’s trade union movement, and the other positing that we spend more (and, by implication, too much) on “administrators” and/or non-academic staff.

Again, category and definitional issues prevent meaningful comparison here – but what I would say is that the panoply of professional services in the UK, especially those that seek to support students and assist them in succeeding (as well as spend on access and participation), do seem to be more extensive than we’ve seen on our SU study tours across Central, Eastern and Northern Europe in recent years.

They’ve come to be a source of pride for our delegations – but while we can see how (for example) student mental health is almost completely dumped on the sector in a way that it just isn’t elsewhere, and our careers support is obviously a lot more expansive (and professionalised), it’s also at least possible that each “service” is highly effective at proving some impact and resultant indispensability, but collectively represents expensive “bloat” at system level.

On the buildings issue, it’s been years since any government put significant capital into that, and UK universities continue to enjoy globally favourable finance conditions that have and continue to cut the cost of borrowing. Given estates investment is something that needs to happen (or we’d write about collapsing ceilings, mouldy classrooms, or overcrowded student spaces) the UK exchequer gets it remarkably cheaply compared to other parts of the world. And anyway, the signals from AUDE are that current belt tightening means that we are building up quite the maintenance debt.

That said, there’s no doubt that our SU study tours across Central, Eastern and Northern Europe in recent years suggest that the UK’s estate is a bit (and in some cases a lot) shinier than many other systems – the ability to borrow, the rapid expansion of the last decade and the need to “look competitive” at least feel as though there’s something in the capex crowing that many undertake. It does feel like the UK is sometimes trying to do a US-style facilities and marketing sell but on European levels of regulation and funding.

What’s not deniable is that the PFI-style deals that have underwritten much of the refurbishment and new build do set a fairly uncontrollable bill to be paid on Day 1 of each financial year, and in some cases those bills are now rising rapidly in line with interest rates – in a way that makes simplistic logic about the sector “cutting its cloth” in line with revenue hard to achieve in practice.

(We see the same arguments in student accommodation, by the way, especially down the smaller end of purpose-built projects. The economics A Level assumption is that if you can get supply ahead of demand, rents will fall – but many of those projects were financed on the basis of the minimum rent ratchets that match interest rates. A continued collapse in international PGT numbers is more likely to cause private halls blocks to collapse than for rents to fall, at least in the short term.)

Hardly any of our students drop out

Some will point to the cost of maintenance and the relatively/comparatively high percentage of students in the UK that leave home to attend university. There’s almost certainly something in that (notwithstanding the loan recovery issue at the top of this piece), but maintenance costs are not included in the OECD numbers – unless you count the ways in which the state expects universities to fill in gaps that other parts of the state leave by leaving “looking after students” to universities. But that gets us into different territory.

Some will suggest that the UK’s comparatively low drop-out rate – and what are assumed to be higher than average teaching and student support costs delivering it – are causing the difference. The suggestion is that if ministers want a system where more students don’t complete, they can have it – but that our success in this space does cost money.

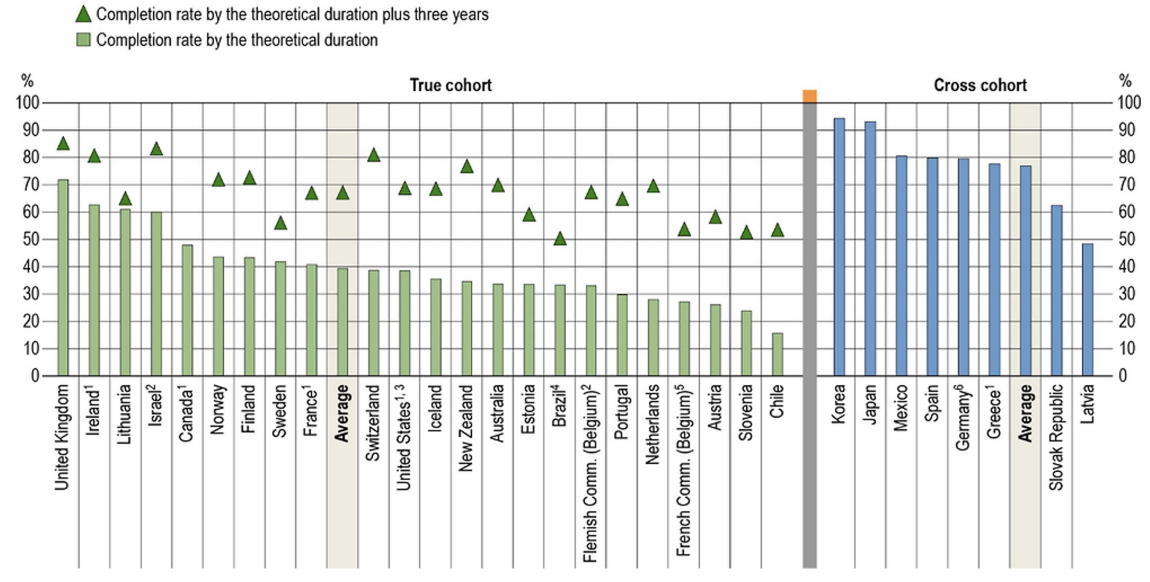

There’s a version of that argument that’s even more compelling – but not one that will sit well with some. If we look at UG FT FD completion by the end of the theoretical programme duration, it is indeed true that the UK does very well:

It’s the triangles that matter in that chart – everyone else catches up fairly close once they give students a bit more time. By definition, that will make the UK more expensive per FTE student per (academic) year, but (much) less comparatively expensive per FTE student per overall degree completion.

As I’ve argued on here before, the UK is pretty expert at getting them in immediately after school, trapping them with hostile financial penalties for pauses and setbacks, and hothousing them to their graduation ceremony by 21 – when other countries allow them to take more time, all while the sector bemoans being treated like “big schools” by DfE.

We may well be discriminating against a growing cohort of Disabled students in the process and causing half of the mental health issues we see via that hothousing, but at least we spit them out into the labour market sooner than most – only for graduate employers to bleat about “skills gaps” when what they probably mean is a mixture of reflections on class and maturity.

If the Lifelong Learning Entitlement was to ever take off, the biggest schism with our OECD comparators won’t be so much everyone’s experiments with modules and microcredentials, it’s that most other systems provide for full-time student support while allowing completion at a slower pace and thus reduced average study credit intensity per year. The LLE isn’t even promising proper credit-chunked maintenance yet.

Students over-specialise here – and that’s expensive

Other theories are available. There is (much) more evidence of systems standardisation in many (smaller) countries, some stuff that universities and students seem to get for free (or cheaper) from the state that UK doesn’t provide, our (esp academic) pensions do look more expensive than many other systems’, there’s considerably less meddlesome regulation in evidence across much of the OECD, and it at least looks like our marketing costs and the resultant cost-per-student recruited is higher than the average – even when differentiated from the (interest-conflicted) suggestion that much of what’s being spent in there is essential information, advice and guidance that the rest of the system fails to provide.

But there is one other argument that I think bears better interrogation – and it’s about choice. Almost without fail, and this is true across both ends of each dual-system we’ve visited in recent years, there’s evidence of less rigid subject-specialisation – and more manifestations of modern versions of liberal arts curricula, degrees achieved by diverse module gatherers, and chunks of core credit that are obtainable via work experience, volunteering to help create the student experience, and interdisciplinary project work.

You don’t need many ECTS credits per year to be obtainable via the latter categories to reduce costs considerably at a system and institutional level – and the more that a university does the former, the more that it is able to apply “demand smoothing” techniques to achieve a decent student experience on what look like higher staff-student ratios than the UK seems to achieve.

When we visited the University of Maynooth in Ireland in February, I was primed to hear of enormous class sizes, high drop-out rates and non-existent student support. What we saw was a liberal arts major/minor undergraduate system able to maintain specialisms that wouldn’t otherwise sustain entire departments, where students pick pathways based on the timetable (rather than trying to craft a timetable based on students’ selections), and where students are combining arts and science and have a generally pretty happy set of students despite what the figures suggest is a 28.5:1 SSR – unheard of in the UK at institutional or system level, but actually pretty common at subject level across our sector.

If nothing else, those in the UK currently running modules with small numbers and spare capacity feeling the threat of bean-counting closure on their back would feel more relaxed if students from outside of their specialism were able to broaden their academic horizons by enrolling onto them.

It’s why that simplistic “cull the courses that are losing market share” kool-aid that university governing bodies seem to be supping on is so daft – every survey of students I’ve ever seen in the UK that asks if more personalised pathways ought to be possible backs it up. I’d have given my eye-teeth to do a smattering of music modules when I was a student, but for a million reasons would never have gone near a music degree.

We do need a plan (and some planning)

Where might that all leave us? The sector clearly does need more than speculation and hunch on the above, and if you’re reading this thinking you might be able to help with that, we’re keen to hear from you here at Wonkhe towers.

One day soon, we might return to a semblance of sensible and evidence-informed policy making – and just not being able to answer the questions “where does the money go” and “why does the UK look so expensive in comparison to other systems” won’t really do.

But on the basis that there are some clues as to how a healthy HE system in the UK might become more efficient for a mass age, leaving universities to achieve that alone won’t do either.

I was floating around a campus in England a few Fridays ago, and I overheard someone in a uniform in a campus coffee shop saying “well there’ll be no one to polish the fucking toilets on applicant days now”. Evidently from the conversation, she’d decided to take VR. I’m reminded of the old adage about people’s job descriptions often not covering the way they actually contribute.

An actual applicant day was on on the following day, so I had a mooch about the emerging stalls and materials. It was heartbreaking. Not only will the educational experience not match what they’re being promised (small group teaching, lots of elective choice etc), neither will the “student experience” – because students will be too skint to take part in it.

Higher education has been through painful cuts before. But never in a period combined with putting its student participants through extreme hardship, and combined also with an intense need to sell the educational and wider student experience positively. Without proper planning and restructuring help, students will enrol, and they’ll be mugged off. And they’ll never be warned that it won’t be as good as they’re being told it will be.

Just as unplanned expansion is so dangerous, so is unplanned contraction. And as usual it’s students – paying for forty years not thirty these days – that will suffer.

It is, I suspect, possible to have a less expensive HE “system” – albeit with difficult choices. But getting there in the way that this government is allowing to happen just means absolute misery. And all because it can’t stand being seen to plan a thing.

Even if you believe to your bones that expansion shouldn’t be heavily planned because it stifles innovation and choice, who believes that contraction should be handled that way? What are “providers” supposed to do now? Compete to make the least damaging cuts?

A new restructuring regime is needed

Back when we all thought Covid was going to cause temporary fee income collapse, the Department for Education pretty rapidly developed a Higher Education Restructuring Regime, that was largely rebuffed and never actually deployed because students paid up and enrolled anyway.

It had four main policy objectives:

- Protect the welfare of current students because of the potential impact on the quality of teaching provision to current students, and the impact on disadvantaged and local students – including differential impact on students with different protected characteristics;

- Support the role HE providers play in regional and local economies through the provision of high-quality courses aligned with economic and societal need;

- Protect teaching provision because of the risk of the loss of strategically important or unique provision, the loss of provision supporting key workforce pipelines, the loss of teaching capacity in cold spots and potential impact on regional businesses, jobs and local growth;

- Preserve the sector’s internationally outstanding science base.

All four of these risks are still present, and all four will matter to an incoming Labour government. Hoping that tuition fees will go up to fill in for the lost years of high inflation feels like a big risk – especially now that £9,250 is worth £5,929 in real terms. The sector should instead call for a version of that restructuring regime to be dusted off and relaunched with urgency.

This is a thorough piece and I hope sector leaders read it and think through the implications. I want to focus for a moment on the system you saw at Maynooth (major/minor with around 28:1 SSR and upper year pathway specialisation). Anyone from North American higher education will be very familiar with similar setups, and I would advocate for a good sustained look at them here in the UK (though they tend to involve a 4th year). After an initial move to this sort of system it does sustain costs and cohorts much better, it enables very interesting student degree… Read more »

very thorough and clear-eyed piece – thank you

Very good points on the issues around completion. If the LLE achieves anything, it will be to change the way we think about completion and our overly prescriptive measures of success.

Just two thoughts. Ireland (like the US) has a completely different secondary school system with much less specialisation than England and students typically take 4 years to reach an honours degree. There are all sorts of reasons for arguing that this is a better approach but cost isn’t one of them. Cherrypicking bits of other people’s systems is good fun but not a good basis for policymaking. The main thing that seems to be missing from this piece and the other one on costs is productivity. I don’t know how many genuinely world class sectors the UK has, but higher… Read more »

Ireland has a better secondary education system where students reach at least A’ level equivalent in 6 not three subjects and in Maynooth, Galway, Cork, UCD the standard u/g hons degree is three not four years. It’s in TCD where the standard u/g hons degree (inflexible like in England) lasts four years.

All the above help to provide additional information to both widen and deepen this important discussion. The way that the school curriculum, qualifications and exams link to university subject specialisation on an international basis is interesting. Many UK universities are now running courses related to foreign languages that are much wider than learning to communicate in the chosen language. However, this does not mean that every UK university should expand to teach pure deep French and wider French – in fact I would suggest the opposite is better. There should be perhaps 50 universities / Language Academies being centres of… Read more »

Really helpful. There was also an interesting piece on HE in this morning’s Sensemaker at Tortoise email newsletter, not least as it’s always interesting to see how those outside the sector present us. It was a summary of the current situation in UK HE, looking at education and research, and a key element was contrasting the high performance of the sector compared to other countries (e.g. second only to the US in league table terms) with the current funding crisis. A key part of the analysis was the comment ‘UK universities punch above their weight thanks mainly to staffing –… Read more »

Really thought-provoking piece! Looking at costs is long overdue in my view and I am amazed it has not had recent attention. But it does require more than attention – it will require significant work to understand the issues. Agonising about costs in HE goes in cycles of about 5-10 years. My personal view of timescales is a bit influenced by the fact that any costs study I get involved in has aspects of digital learning. But it goes something as follows – bursts of activity followed by silence, somewhat correlated with global economic shocks and often ended by “distractions”… Read more »

After working in the sector for 20 years I have come to the conclusion that universities try to do too much across a vast range of activity, which entangles them in a range of different compliance/ regulatory regimes. To some extent this is a ‘hedge’: be as broad-based as possible (in terms of subjects taught, but also functions) to access different revenue streams and so on. But I do think it stretches unis a bit thin, adds complexity and costs, and in some cases leads to a drift away from core functions: teaching and research.

Interesting piece as always and really speaks to the importance of access to robust benchmarking data. Importantly, the article highlights the difficulty some universities have in accessing insight around what activity/services should/could cost because of the complexity of the institution and the inconsistencies with how similar activity could be organised elsewhere. It’s worth reflecting on the importance of two themes within the article: transparency and consistency, and the value of thoughtful, independent, and evidence-based benchmarking to strengthen the sector’s voice and provide a clearer narrative. Before we can confidently assume that UK HE could be “cheaper to run”, we need… Read more »

Overall interesting piece. However the role of actual research costs in this story is once more unclear. It is briefly suggested that research is sucking money out of the education budget which apparently is also cross-subdising some low-impact research activities. Probably this argument is referring to the 20% FeC matching requirement (see Wonkhe piece “University funding is driving the research funding deficit”), which I believe is an artefact of the TRAC system where university operational costs and opaque overheads are cross subsidised through research grants. In many other countries on the list there are much clearer parallel systems for research… Read more »

Unfortunately our sense of value when it comes to education has been severely eroded over the last 45 years here in the UK. Thatcher policies combined with a sterling bailout has led to many years of decline. As AI replacesd more and more jobs, the government will have to step in and create jobs through research and development to help fill the void – as capitalism doesn’t care.