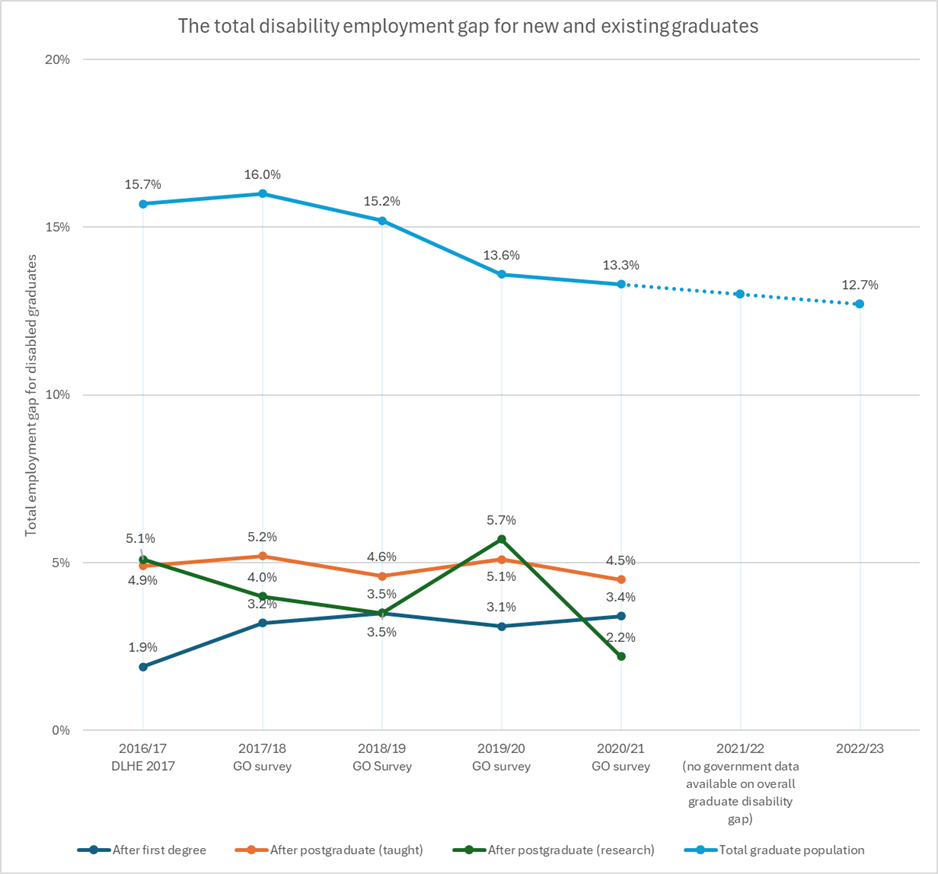

In the most recent Graduate Outcomes data, the employment gap between disabled graduates and graduates with no known disability was 3.4 per cent – for recent first-degree holders. Across the whole graduate population, the gap was close to ten percentage points higher.

On a first look, this suggests that the disability employment gap is closing over time, with recent graduates less affected than earlier graduates. This is positive news. Isn’t it?

It may not be this simple. Comparing recently published employment outcomes for disabled graduates with data on the national disabled graduate workforce poses important questions about the gap and how we can improve the longer-term lived career experiences and outcomes of disabled graduates.

Gap and pipeline

This morning, the latest What happens next? report from AGCAS was co-launched with The disability employment gap for graduates research from Shaw Trust. AGCAS’s research demonstrates that, 15 months after the 2020–21 cohort graduated, the total disability employment gap was 3.4 per cent after a first degree, 4.5 per cent after a postgraduate taught degree and 2.2 per cent after a postgraduate research degree.

Total employment is the sum of graduates in all forms of employment – full-time, part-time, voluntary and employment and further study. The total disability employment gap is the difference between this calculation for disabled graduates, and for graduates with no known disability.

Data from the Department for Work and Pensions shows that across the whole graduate population, non-disabled graduates are around 12.7 percentage points more likely to be in work than disabled graduates in 2023, and this figure has been slowly dropping over recent years.

The steady fall in the total graduate disability employment gap is certainly encouraging. But it leaves us with questions. Why does the total disability employment gap persist for new graduates – the graph below shows how little this has changed in recent years. And why is the total employment gap experienced by disabled graduates during the course of their working life greater than the gap that they initially experience as a new graduate?

Total graduate population data source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/the-employment-of-disabled-people-2023 (Table LMS006)

One potential explanation lies in the phenomenon of the “leaky pipeline” of continued workforce participation and progression. This has been discussed across multiple groups, including diversity in academic leadership. A disability employment gap of 3.4 per cent immediately after an undergraduate degree and an average disability employment gap of 12.7 per cent in the wider graduate population does not necessarily mean linear progress from the graduates of previous decades to more recent cohorts.

It could mean that disabled graduates leaving university potentially experience fewer initial barriers to employment, but subsequently find that obstacles and challenges worsen with time, leading them to leave the workforce. This suggestion is not intended to minimise the significant challenges faced by disabled people who have recently graduated.

Any consistent employment gap for disabled graduates, at any point in their career, is completely unacceptable.

The leaky pipeline analogy has been criticised as implying an inappropriate level of passivity. We agree and are using it cautiously here. The pipeline is not so much leaky as blocked, to the detriment of our society. The barriers that disabled graduates, and the wider disabled population, experience in seeking, securing and maintaining good work are significant, varied and complex. Disabled people are often actively excluded from employment, directly or indirectly, as illustrated by the overall disability employment gap.

A complex set of issues

While we are considering the collective experiences of disabled graduates in our recent work, we have identified that some groups within this population experience even greater disadvantage. As What Happens Next? demonstrates, autistic recent graduates have the lowest levels of full-time employment. They also frequently have higher levels of part-time employment and unemployment, and lower levels of job security and highly skilled work. Today’s publication of the Buckland Review shows how timely this work is.

It is also worth remembering that our new research projects only focus on accessing work. Once in work, disabled people continue to experience inequality, with the disability pay gap currently standing at 13.8 per cent. There is a long way to go here.

Another complex issue that affects our ability to clearly assess what is happening within this data is around disclosure. Many disabled graduates will make decisions about whether to disclose their disability to their employer. Choosing not to disclose limits their ability to access reasonable adjustments in the workplace but may make it more straightforward to access employment.

Shaw Trust’s video interview with Dr Shani Dhanda, disability advocate and Disability Power 100 winner in 2023, explores her personal experience with disclosing, noting that removing her disclosure from applications led to interviews that had not been forthcoming when she was more open with potential employers.

While in education, the decisions around disclosure are potentially different, but still complex. Many students make a “conscious and strategic choice” about when and how to disclose, and this can lead to them not being recorded in official statistics, and thus unable to access support. This means that multiple hidden disabled populations may exist within the Graduate Outcomes data – students who choose not to disclose, graduates who became or identified as disabled after their studies (who may not be accurately captured in Graduate Outcomes as it is based on their student record), and graduates in work who are cautious about disclosure.

Disabled graduates also need to feel confident that disclosure to a potential employer will not affect their ability to secure a role. This can be supported by employer education and accreditation. As a Disability Confident Leader, Shaw Trust works with employers to help them gain the knowledge and practices they need to become an accredited Disability Confident Employer.

On the other side of the conversation, recent AGCAS research shows that over 90 per cent of careers services offer two or more years of ongoing support to their graduates, with over one third providing lifetime support. Careers professionals within universities frequently support their students and graduates with conversations around disclosure and reasonable adjustments, while at university and beyond.

What happens next?

Collectively, these new reports share vital data and lived experiences from disabled graduates, but they also raise questions.

AGCAS and Shaw Trust would like to invite critical consideration of the continued existence of the disability employment gap and encourage higher education institutions and employers to work collaboratively towards greater knowledge and understanding of the disabled graduate experience, to create meaningful change and impact.

Employers who have had issues with previous ‘disabled’ graduates will always look closely at potential issues is they declare, if they don’t declare then they hand the employer the means for dismissal, and whilst large employers might say we’ve the capacity to cope smaller employers may take the safer option and not employ. Physical disabilities can be limiting but easier to assess and adjust for, mental disabilities are much harder to assess and often ‘reasonable adjustment’ is anything but.

Personal declaration: I’m physically disabled and a former company director, so I’ve seen this from both sides.

Very interesting article, thanks for the data and the views!