There are some, when considering the very worst of the bureaucratic processes that institutions and academic staff have suffered from, that would point to the sheer administrative overload of the Research Excellence Framework. Others, perhaps with longer memories, recall the uncertain panic of the Centres for Excellence in Learning and Teaching. And those that go even further back will suggest, unhesitatingly, the brutal Subject Review process.

Unerringly, the long awaited TEF proposals in today’s Green Paper have drawn from very worst aspects of these three initiatives to produce something outstandingly bad. Not only will the TEF not do what it has been designed to do, not only will it add to institutional burdens and spawn new internal processes, not only will it generate endless questions and challenges for whoever in the Office for Students (OfS) is forced to run it, it will also not reward institutions or excellent teaching staff in any meaningful way.

Readers may, at this point, be thinking that I am overegging the pudding somewhat. Surely this is just exaggeration. Let me break it down.

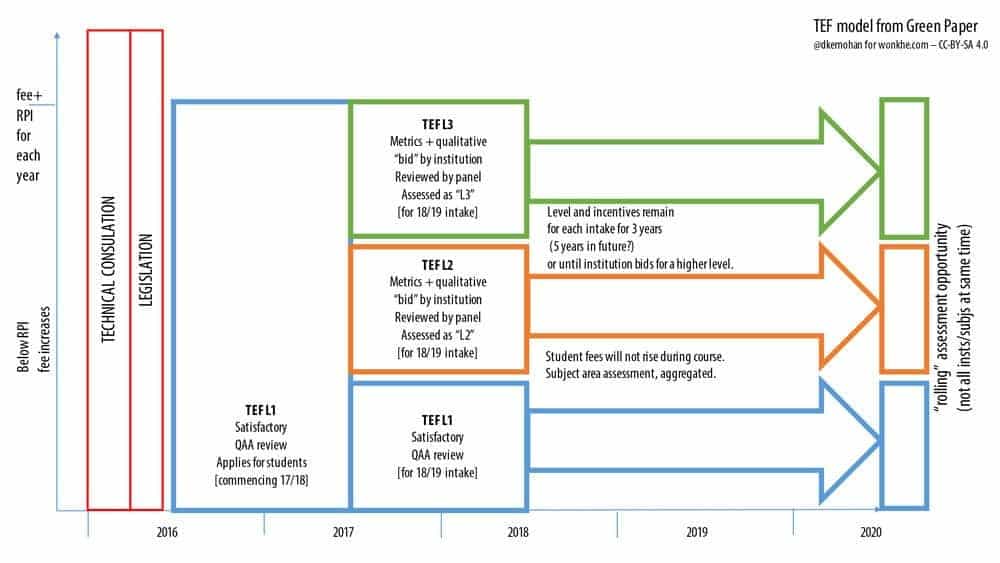

First up, year one (assessed 2016, fees increased from 2017). If an institution passed the most recent QAA inspection (rated as being at the UK standard in each of four areas), it is allowed to increase fees by inflation. I’m guessing RPI (currently 0.8%), not least because CPI currently stands at -0.1%. By “passes the most recent QAA inspection” BIS suggest that an institution should have a a current, successful Quality Assessment (QA) review defined as:

- the most recent review undertaken by the QAA or an equivalent review used for course designation (e.g. an ISI review);

- which is published by the end of February 2016;

- with a judgement of “meets UK expectations” or higher (for example, commended) for each of the four areas which are setting and maintaining academic standards, provision of learning opportunities, provision of information about learning opportunities and enhancement of quality of students’ learning opportunities.” (para 27, chap 1)

In most cases, this will refer to the recent QAA Higher Education Review cycle, which is scheduled to be complete by the summer of 2016 – a good few months after the February deadline. So for King’s College London, to give a well-known example, it is not clear what review will apply for TEF purposes. Their most recent institutional review was published in 2010, but this does not give scores in the same format as the Higher Education Review.

In 2014, 96% of universities reviewed would have met the required criteria for TEF level one. The 4% represents one HEI that was judged as needing improvement in the area of enhancement. Whilst this is good news in terms of the overall quality of English HE, the upshot is that just about every university will be eligible to raise fees under level one of the proposed TEF.

And, of course, the current QA mechanisms are subject to the findings of the HEFCE consultations that closed in September. If this consultation results in changes to the methodology, judgements about TEF awards will in part be based on reviews that have been identified as not meeting sector QA needs.

So to summarise the problems with using HE Review scores to award L1 of TEF to affect fee levels in 2017-18:

- Not all institutions will have a qualifying review report by February 2016. Reviews are scheduled to report as late as Summer 2016.

- The review method does not discriminate well between institutions, with the likely upshot that most eligible HEIs will be awarded TEF level 1.

- The review method in question is subject to a review based on a consultation held over the summer, and changes to the review method will throw the validity of existing scores into question.

If George Osborne had not chosen to announce the link to fee levels in the Budget earlier this year, it seems most likely that TEF as a whole would have been delayed until 2017. Instead we get a blanket increase in fees in all but name, but with added complications linked to poor design.

Let’s move on to what we have of the ‘meat’ of the TEF proposals, those examining TEF level two and above: a technical consultation in 2016, bids made in late 2016, announcement of results in spring/summer 2017 and applying to fee levels from 2017-18.

The incentive, briefly, is a differentiated fee increase with a different “cap” at each level. But (Chap 2, para18) this is not to exceed “real terms” (again guessing RPI) increases. The effect being that an institution jumping through the myriad flaming hoops required to access TEF level 3 (or 4, because for some reason whether there are 3 or 4 levels is up for consultation) will be rewarded by the ability to increase fees by inflation. Those shooting for level 2 (or 3) – because that’s going to be hugely popular – will get a below inflation increase, as will those who sit tight on level 1, holding their shiny QAA review and doing the barest minimum to support teaching excellence.

Remember that unless the much vaunted “long term economic plan” defies expectations and starts producing growth, these are fee increases of fractions of 0.8%. For example, the University of Surrey (8,800 first degree UG students) if it achieved the highest TEF level) would net a sweet £639,000 a year – 0.29% of their annual income. So to win that massive prize, what hoops would an institution need to leap through?

An independent assessment panel will be assessing institutional “bids” for a stated level of excellence (so an institution chooses explicitly to bid for levels 1-3 (or 4)) – they will look at both a standard set of metrics and an institutional submission of qualitative evidence.

I’ll come to the metrics in a second, but the qualitative submission is giving me CETLs bid flashbacks. Anyone who was involved in submitting or assessing those bids knows the sheer size, variability and incomparability in things like this. Especially when produced at a central institutional level. For those who love massive bureaucracy, these bids will eventually be made at subject area level and then aggregated to offer an institutional benefit. Paragraph 17 of chapter 3 suggests some possible aspects of the qualitative evidence:

We are not being prescriptive here about the additional evidence providers might want to offer and will consult further in the technical consultation but these might include:

- Further information about the institution’s mission, size, context, institutional setting, priorities and provision

- The extent to which students are recruited from a diverse range of backgrounds, including use of access agreements where relevant.

- The ways in which an institution’s provision reflects the diversity of their students’ needs.

- The levels of teaching intensity and contact time, and how the institution uses these to ensure excellent teaching

TEF was initially sold as a metrics-based approach to teaching quality. This was before the release of James Wilsdon’s superb piece The Metric Tide, which highlighted the perverse and often destructive effect of improperly used metrics on research excellence framework assessment (and, more tellingly, of the institutional structures that had been built around these metrics). Perhaps it was this report that prompted paragraph 13 of chapter 3:

However, we recognise that these metrics are largely proxies rather than direct measures of quality and learning gain and there are issues around how robust they are. To balance this we propose that the TEF assessment will consider institutional evidence, setting out their evidence for their excellent teaching.

The Green Paper suggests three metrics that could be used in the initial iteration of the full TEF as national comparators. These are (Chapter 3 para 12):

- “Employment/destination – from the Destination of Leavers from Higher Education Surveys (outcomes), and, from early 2017, make use of the results of the HMRC data match.” One would hope that the subject mix, the socio-economic background of students and the economic activity of the area surrounding the institution would be taken into account here.

- “Retention/continuation – from the UK Performance Indicators which are published by Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) (outcomes)”. One would hope that at the very least non-typical length UG awards and placement learning are taken into account.

- “Student satisfaction indicators – from the National Student Survey (teaching quality and learning environment)”. There are so many issues with comparing NSS results on an institutional aggregate level that I feel at a loss to cover them in an overview like this. It is also worth noting that the NSS itself is under review.

According to the Green paper, “the sector” has also suggested some further metrics:

- “Student commitment to learning – including appropriate pedagogical approaches“ – I’m not sure how this is going to be measured.

- “Training and employment of staff – measures might include proportion of staff on permanent contracts” – This is almost sensible by the standards of other suggestions.

- “Teaching intensity – measures might include time spent studying, as measured in the UK Engagement Surveys, proportion of total staff time spent on teaching”. – And this isn’t as sensible. Not all courses require “intensive” teaching – for instance an English Literature course that programmed lectures and seminars from 9-5 every day rather than giving you time to read books would be a bit of a problem. And measuring the total staff time spent on teaching seems potentially counter-productive.

Coupled with Learning Gain and engagement with study (“when these become suitably robust” i.e. don’t hold your breath…) this latter set would be phased in over future TEF iterations. Also having implemented Grade Point Average (GPA) alongside degree classification will be looked at, but will not be a requirement.

The assessment panel – which is “made up of a balance of academic experts in learning and teaching, student representatives, and employer/professional representatives.” para 9 chapter 2 – would seemingly examine the central metrics alongside the institutional evidence presented. They wouldn’t expect to visit institutions, although this may happen in exceptional circumstances. Judging by the rolling nature of TEF, the level and size of likely submissions and the sheer number of institutions that may apply (TEF includes public and private universities, FE colleges that deliver HE and a range of other providers – eventually at subject rather than institutional level, remember), it is possible that these panels may need to be full time appointments.

Although there has been an attempt to minimise duplication with QA activity (the findings of the consultation and the responses to these may make things clearer) this looks like a significant addition to sector bureaucracy. At a moment when sector regulation is under scrutiny and simplification is the order of the day, TEF feels like a throwback to the 2003 White Paper or earlier. This is big regulation.

But the real missed opportunity is the entire lack of incentive for staff who teach. Though the REF has many flaws, the need to be “ref-able” is an important driver for many academics. The individual research can see her activity reflect in the success of their department or institution, and benefit (on occasion) from the increased availability of research funding. With TEF there is no link between individual teaching performance and the assessment of teaching excellence.

The use of metrics and institutional evidence serves to standardise practice rather than incentivise excellence – in targeting managers “excellent teaching” as a concept is almost completely lost.

Brilliant summary DK – all excellent points and the final one is the clincher. Love your work!

I can’t be the only one who feels a strange sense of freedom reading this though… all the frantic discussions and efforts from the teaching community to get our voice heard, and – hey presto – another metric that we struggle to relate to – indeed to find any meaning in whatsoever.

Let’s all imagine a better world and choose to live in that instead 🙂

Thanks Lindsay – of course the green paper is a consultation (deadline in mid-Jan) so maybe the teaching community can still make some realistic changes happen. I’m afraid we have to stay in this world for a while yet…

Well, it’s certainly a “Framework”. I just don’t see how it links to encouraging (or indeed rewarding) Teaching Excellence.

Will this “framework” disincentivise institutions who have recently made efforts to reward excellence in learning and teaching more? That would be a deplorably retrograde step.

Thank you David for your analysis and perception. I was in despair when I read the green paper. Now I’m in much better organised and clarified despair. The TEF proposals are not even the worst things in this paper: not by a long way. I second Lindsay I’m afraid.

Thanks for the analysis, David. This will really help with our response to yet another consultation but not sure if anyone is listening. Nice to know all the hours already spent on institutional Quality Review and CANTF consultations have had their desired impact. One might even become cynical! Hey ho.