I recently wrote a review of a book on university governance, in which I noted how the book describes the shift over the past century from

a wholly self-governing to a more highly regulated system and articulates both system governance and institutional governance up to the introduction of the new Office for Students. The authors argue that the effect of OfS powers is that the new rules mean that universities have moved from substantive autonomy to “operational autonomy, which is circumscribed by the new Framework Regulations”. This is a significant development from the previous regime in England where “HEFCE represented a force of advocacy towards sensible and institutionally manageable decisions on policy”.

A couple of years ago I also speculated, rather pessimistically, about the impact the new regulatory regime ushered in by the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 and the establishment of the Office for Students was going to have on regulation in the sector.

Things can only get better

Given the libertarian urge which seems to be part of the dominant political narrative at the moment and particularly the Government commitments about significant reductions to the bureaucracy associated with research grant applications, are there any grounds for a more optimistic view of the direction of higher education regulation in England (acknowledging the different, but OfS-free, challenges in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland)? It looks unlikely.

Quite a few years ago I published Dangerous Medicine, a book all about the problems with academic quality assurance and standards (and still available at a bargain price on Kindle, with some bits, mainly the historical stuff, as fresh and relevant as ever as the sole 5 star review confirms). The core thesis was that the attempt to regulate quality and standards in higher education was actually damaging the very thing it purported to assure. At that point my primary concern was with external academic quality assurance.

The world has moved on and the Quality Assurance Agency, the body about which I was most concerned at the time, has become much more of a sensible, proportionate and pragmatic regulator of quality assurance than I ever anticipated. Indeed, in the current regulatory landscape it now appears as a beacon of rationality, rather than the rather malign outfit I once portrayed it as. I’m sure the QAA would argue that it hasn’t changed but it is in fact the environment and polemical critics (eg, me) have. Perhaps, but in any case, the concern here is absolutely not about the QAA but rather the remaining elements of the regulatory landscape.

Meet the new boss

Foremost amongst these, in England, is of course the Office for Students (although we need not to forget the CMA, UKVI, the OIA, the ICO etc etc).

As it was being established the OfS published its Regulatory Framework, a dense 164 page document which set out how the OfS intended to perform its role and covered: the OfS’s risk-based approach; sector level regulation; regulation of individual providers; validation, degree awarding powers and university title; guidance on the general ongoing conditions of registration.

A couple of key extracts, first the opening sentences:

1. The Office for Students (OfS) is a new regulator for English higher education. It will adopt a bold, student-focused, risk-based approach, reflecting the significant changes to higher education of the last 25 years and seeking to anticipate the changes still to come.

And then – the four primary regulatory objectives:

The four primary regulatory objectives

All students, from all backgrounds, and with the ability and desire to undertake higher education:

1. Are supported to access, succeed in, and progress from, higher education.

2. Receive a high quality academic experience, and their interests are protected while

they study or in the event of provider, campus or course closure.

3. Are able to progress into employment or further study, and their qualifications hold

their value over time.

4. Receive value for money.

It’s all about the students which, despite the name of the regulator, many still seem surprised about.

A matter of perspective

The history of regulation in higher education in England has been one of continued growth, which has accelerated significantly in the past 30 years. For 60 years after the end of the First World War, the University Grants Committee, a genteel club of funding allocators, was in charge but after the cuts began in 1981, things moved pretty rapidly from the UGC to the UfC (and PCFC) before we saw the advent of HEFCE (in England) following the 1992 FHE Act and then the QAA, Dearing, fees, Browne, HERA, then Augar and now we are here.

As an indicator of how much things have changed, a decade ago the sector was very concerned with what felt like a disproportionate, overbearing and costly regulatory regime and a succession of review groups was established to address this issue. This activity ended with the final report of the Higher Education Better Regulation Group back in 2014. The final report is still available; the principles on which the HEBRG’s work was based were agreed in 2011:

The HEBRG Principles (2011) were developed through consultation with members, and apply to organisations that have a direct responsibility for regulating or holding to account any aspect of higher education provision offered by UK institutions. There are six principles:

1. Regulation should encourage and support efficiency and effectiveness in institutional management and governance.

2. Regulation should have a clear purpose that is justified in a transparent manner.

3. Regulation depends on reliable, transparent data that is collected and made available to stakeholders efficiently and in a timely manner.

4. Regulation assessing quality and standards should be co-ordinated, transparent and proportionate.

5. Regulation should ensure that the interests of students and taxpayers are safeguarded and promoted as higher education operates in a more competitive environment.

6. Alternatives to regulation should be considered where appropriate.

The contrast with the OfS regulatory objectives is pretty striking, not least because there is only one HEBRG principle which refers to students and the focus is very much on institutional and sectoral perspectives. This feels though like a set of principles which we need to remind ourselves of in considering the welter of regulation faced by the sector.

Registrarism’s Law of HE regulation

Anyway, as everyone seems very fond of saying these days when they find themselves in a place where they absolutely do not want to be, often as a result of unwise earlier decisions, we are where we are. So, where is that exactly? In general terms, I would suggest we are in an over-regulated, disproportionately interventionist and not at all risk-based regulatory environment. I used to argue that there was an iron law of university regulation which was that as funding declined the level of regulation increased. I now have to admit that the argument about there being some correlation with funding was completely wrong. The law is simply that in higher education, over time, there is simply an inexorable growth in the range, impact and cost of regulation on higher education.

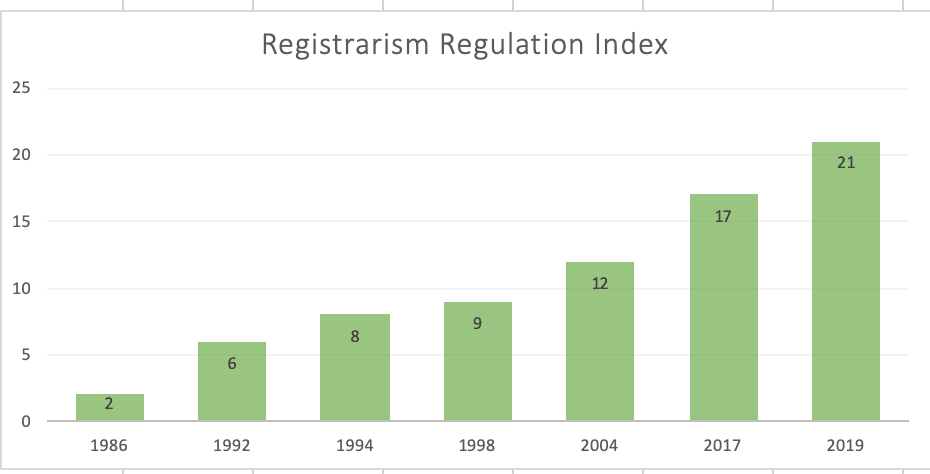

Here’s a completely made up graph which demonstrates this law:

Pretty convincing I am sure you will agree.

(DK notes: I have several questions…)

More, more, more

There’s a lot of talk around these days about regulation in relation to degree classification and grade inflation, unconditional offers, widening participation and admissions as well as somehow eliminating “low value degree courses”, all of which indicates that this trend is unlikely to reverse any time soon. If we add to this the dark mutterings about the need for an “Ofsted for universities”, which is one of my favourite regulatory threats, and what are now approaching 20 formal pieces of additional Regulatory Advice issued by the OfS since its inception, you get an impression that the only way for regulation in the sector is more, more, more.

How should we respond to this regulatory avalanche? Part of the response from many institutions has been the quite rational step of appointing new professional staff and developing new oversight structures to ensure appropriate compliance with the expanding external architecture and the growing regulatory demands. Of course in a more sensible regulatory regime this kind of approach would not be required. Nevertheless, in order to mitigate the excesses of the external interventions and to minimise the impact on core teaching and research and the day-to-day activities of academics, it has to be part of the role of professional services staff in universities to absorb, respond to and deal with these regulatory interventions. There is very little in any of this which enhances the experience of students or creates a more conducive environment for learning, teaching, research and knowledge exchange.

Regulation costs and more regulation carries more costs. Excessive regulation endangers the very things it aims to protect. The Government has rightly focused on addressing some of the regulatory requirements around research grant awards. It would be a sensible and welcome next step to consider focusing on cutting back with equal enthusiasm some of the greatly burdensome regulation afflicting many other parts of university activity.

If I could throw my hat in the air and shout hurrah I would, but as I’m in a train right now and not wearing a hat I can only shout hurrah to all that!

Excellent summary of the growth in this self serving employment scheme. In my experience it contributes nothing to Quality, but adds enormously to costs reducing resources available to teaching and research. It long overdue that we get some quality into Quality