Simple: ignore administrators (or worse)

The recent launch of the “Council for the Defence of British Universities” (or CDBU) offered some fascinating insights into a particular corner of British society. Like a strongly worded round robin letter to the Times made flesh it attracted some big names from Sir David Attenborough to Baroness Deech. A rather wry report of the event was published over at WonkHE:

At the root of many contributions appears to be a reaction against the suggestion that academics ought to justify their own existence or the funding they receive. If Plato’s philosopher kings were not expected to appear before the Audit and Accountability Scrutiny Committee of Ancient Greece, why on earth should The Great and the Good of the British Universities?

It doesn’t end here. We hear praise for the University Grants Commission Lloyd George created in 1919 and “lasted us well” for 70 years before its untimely abolition, and later, Francis Bacon’s 17th century “partition of the sciences”. The message is clear – time to go back to the future and the further the better.

In addition a piece in THE on the launch of the CDBU noted that:

The council’s initial 65-strong membership includes 16 peers from the House of Lords plus a number of prominent figures from outside the academy, including the broadcaster Lord Bragg of Wigton and Alan Bennett. Its manifesto calls for universities to be free to pursue research “without regard to its immediate economic benefit” and stresses “the principle of institutional autonomy”. It adds that the “function of managerial and administrative staff is to facilitate teaching and research”.

This rather dismissive comment from the launch manifesto about administrators has been reinforced by the comments by Professor Thomas Docherty (someone for whom I have high regard) who has penned a provocative piece for The Chronicle of Higher Education about the new body. In this article he observes that there are, apparently, two remarkable things about this council. First, it has a membership of very distinguished academics (always a good start for a campaigning organisation that). But there is more:

The second notable thing is the council’s unique mission: It is the only group that exists to put university education back into the hands of universities, and to do so with the determination to reinstate the primacy of academic values. The council has issued a Statement of Aims that should form the basis for how the nation approaches the management of universities, their financing, and their social, cultural, and economic importance. Central to the aims is university autonomy and respect for the independent demands and exigencies of scholarly work.

Corporate management might conceivably be good for some businesses, but it has no place in the university sector. Our administrators need to serve the primary academic functions, but increasingly—and in this they simply replicate a more general social malaise—administrations exist to perpetuate themselves, like some kind of carcinogenic cell that threatens the academic body.

The council hopes to exert influence in Britain, but the common good it wishes to serve goes beyond our borders. I hope American scholars also find that the moment is ripe for the reassertion of academic values and join us in our work. We’ve already received suggestions about the formation of sister councils outside Britain, and we’d certainly welcome an American counterpart. As is clear, the threats to academic values are not just local to Britain: They are global.

Now as has been noted here before, there are rather a lot of administrators in universities. No doubt some in the CDBU would say too many. Are all of these people actively organizing against the fundamental interests of higher education? Are they essentially concerned with protecting themselves and bureaucracies at the expense of academics? Are they unable to support or even understand academic values? Are they simply stooges of the Department of Business Innovation and Skills? Are all administrators merely unwitting dupes in thrall to a neo-liberal marketisation agenda? I don’t think so.

In most institutions, the primary concern of the professional administrator is to support and encourage the best academics to do what they do best, to minimise the distractions and to reduce the unwelcome and bureaucratic incursions of the state into academic life. Administrators are concerned more than anything with protecting academic staff (often with some difficulty) from the worst excesses of the increasingly challenging and turbulent world in which universities operate.

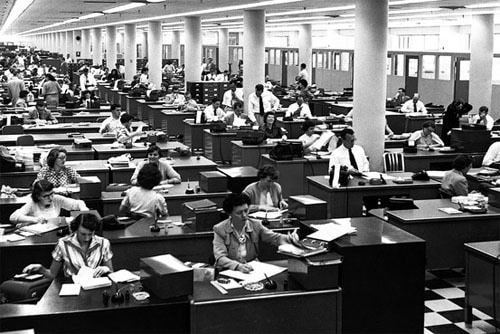

In order for academic staff to deliver as best they can on their core responsibilities for teaching and research it is vital that all the services they and the university need are delivered efficiently and effectively. Universities do not seek to hire and retain world-leading scholars in order to get them to maintain IT systems, organise data returns to statutory agencies or look for good deals on electron microscopes. These services are required and professional administrative staff are needed to do this work to ensure academics are not unnecessarily distracted from their primary duties.

So, in some ways I agree with the CDBU proposition that the “function of managerial and administrative staff is to facilitate teaching and research”. However, it is the tone and place of this within the opening statements which originally troubled me and now causes even more alarm following Professor Docherty’s rather unfortunate comments.

Put simply, it looks to me as if, for the very great and extremely good of the CDBU, administrators are, at best, an afterthought. That would be the most benign interpretation one could put on the statements from the initial meeting and more recently from Professor Docherty. Because really it does seem that administrators are to be neither seen nor heard (check out that initial list of members again) and have no place in doing anything as important as defending higher education. Despite the critical role we play in the operation of HE, it seems we are really to be seen as humble functionaries with no part to play in the grand drama of university defence.

If a university prefers to see administrators merely as a servant class or indeed decides that many can be dispensed with through radical surgery to ensure that academics retain the whip hand then it might find it will struggle before too long. Whilst the nostalgia-infused senior common room debates and the delightfully sweet taste of golden age governance will undoubtedly sustain many of the leading participants of the CDBU it won’t be too long in their universities before the infrastructure and professional staffing required to maintain a 21st century institution atrophies and dies. So, the cancer-causing administrators may be excised but it will turn out that this is rather dangerous medicine that the Council has decided to prescribe. Indeed it looks a bit like retreating to 19th Century quackery when modern health care is available. All in all I fear it is a recipe for decay and decline and, you have to say, really isn’t a very good way to go about seeking to build a coalition in defence of universities.

Great critique. Thanks!

I’m an academic currently working in administration, like a few others. The idea that academics need protection from bureaucratic intervention is a familiar one, and many have certainly contributed to it with some strategic learned helplessness on the matter of filling in forms etc. But secretly, we can walk and chew gum at the same time, whatever the stereotype endlessly rehashed in bad college movies.

Whenever we’re characterised as needing protection from the day-to-day so that we can “do what we do best”, it’s often a short step to not troubling us with the bothersome detail of, say, a significant divisional restructure or strategic planning swerve. And our gripe at being left out of this conversation isn’t as peevish as it sounds, but rather it’s a practical observation that if you exclude from administrative decision-making the people who have front line experience of whatever service or function you’re trying to improve, there’s much more likelihood that you’ll have to do it twice.

In this climate of blame that’s currently dividing the two cultures of university professionals, and underresourcing both, what’s really hard to sustain are practices meaningful shared governance, that we can all work together to defend. I’m interested to know what you think.

This is a characteristically thoughtful piece from Registrarism; and a good and welcome corrective to possible misunderstandings of what CDBU is standing for. It also gives me the opportunity to clarify the position as stated in the Chronicle blog and elsewhere. Administration is a crucial aspect of University organisation and management; and I and my CDBU colleagues would happily acknowledge and endorse this. Administrators are themselves often indispensable allies in furthering and bolstering the kinds of academic cause that we list as our Statement of Aims. However, something in the relation is not always as it might be. This takes two forms: a) the occasional tendency for translation of administration into managerialism; and, as a consequence, b) the tendency of managerialism to breed more managerialism, in potentially endlessly self-referring and self-reflexive fashion.

Managerialism – a state of affairs in which a supposedly objective system determines judgements and outcomes for any administrative issue or problem – is anathema to managing. Managing requires involvement in detail and, crucially, the acceptance of responsibility, by specific and identified individuals, for judgements that specific individuals (managers) might make. Managerialism, by contrast, leaves no one responsible for anything, and replaces responsibility with ‘accountabilities’, where the accountability is really to the system of templated decision-making processes itself, and not the facts of the ground that require judgement or managing. I am confident that Registrarism is as opposed as I would be to the negative effects of such a state of affairs.

Further, when no one is responsible, but all are ‘accountable’, we find ourselves not just accounting for a decision, but also accounting for the process of accounting itself. In extremes, this is where an audit culture veers into a near surveillance culture. Instead of being seriously concerned with the University’s place in the world, the result is endless self-reflections on our own practices; and it is this introspection that I suggested as a further danger. There is a world to serve – on that Registrarism and I would agree, i am sure – and it is not always best served when external, misplaced governmental directives endlessly drive us towards an introspection that gets in the way of our serving the public good.

Registrarism is not, by any stretch of imagination, an enemy. On the contrary, anyone who cares as much about the sector as he does, is surely a friend and a key defender of what CDBU is trying to stand for. We need to maintain good relations within our institutions; and I look forward to the continuing dialogue and engagement that Registrarism makes possible.

But actually, it’s really quite sad that Universities need to be defended at all and unseemly that those doing the defending should even hint at a squabble. From Australia, CDBU all feels rather quaint but my sense is that it matters. As, essentially,a career administrator who has had the pleasure of working with Professor Docherty, I admire and respect his willingness to raise his hand. Likewise, Registrarism is a sane and entertaining voice that cares about Higher Education. Partnership (real partnership) between those who research and teach and those of us who endeavour to create the conditions whereby that can be the best research and teaching possible has been (and always will be) key.