£500,000 fines for “Mickey Mouse” courses.

As I type, I don’t actually know whether that will end up as a headline to accompany the launch of the formal consultation on “baseline outcomes” that the Office for Students will expect English higher education providers to deliver as of this September.

It was the front page headline that the Telegraph ran with when OfS launched an earlier “phase one” consultation on outcomes regulation back in November 2020, and judging by the pre-briefing given on this iteration to the Sunday Telegraph this weekend, I suspect I’m not far off.

Blowing its previous 72 page, 28,000 word phase one consultation record right out of the water, this time we’ve got whopping 151,689 words telling us that providers are going to have to reach minimum continuation, completion and progression rates – across the whole provider, within each student characteristic, within each “level” of study, within each subject and within each type of legal relationship with a student – and if you fall below those minimums, there’s trouble ahead.

Or put another way, if we’re looking at full time first degree students, 85 percent will need to make it to their second year, 3 in 4 will have to complete, and 6 in 10 will have to get a graduate job or go on to further study. And that’s not just an average that will apply across the university – it will apply within multiple “pockets” too.

It’s easy to miss something you’re not looking for – but in reality the answer to the question “what is a low value course” has been repeatedly answered multiple times both by ministers and by the Office for Students over the past couple of years. It’s about lots of things, but for ministers and their regulator, in principle it’s mainly about student outcomes. This package of spectacularly lengthy and impenetrable documents explains exactly how that principle will work in practice.

The slow emergence of what we’ve called the “B3 Bear” is a tale we’ve told on the site over the past few years in several stages, and I will attempt to not repeat previous blogs here – but if you fancy disappearing down the rabbit hole (or in this case, bear cave), you can find previous coverage, explanations and debates on the B3 bear tag on the site.

The important thing for a large number of providers in the sector is that while we might think that subject TEF was killed many months ago, in fact in England a kind of mutant minimums version is now about to appear – that will have huge impacts on how performance is judged both inside and outside of universities.

Quality took time

So how will all this work? OfS’ conditions for being on its register of higher education providers include some that are about “quality” (the so-called B conditions), and as well as a bunch of qualitative aspects (which are the subject of a separate but linked consultation process), there’s one focused on numbers.

In the phase one consultation, OfS proposed that Condition B3 would continue to focus on a provider’s absolute performance over time in relation to three student outcome indicators, each in aggregate and over a time series of four years:

- Continuation – the proportion of students continuing on a higher education course after the first year – helps OfS understand whether a provider is recruiting students able to succeed through the early stages of its courses, with the appropriateness of recruitment and student support under the spotlight;

- Completion – the proportion of students completing a higher education qualification – provides a similar look but this time over the whole student lifecycle (and also means that there will not necessarily be a direct, linear, relationship between a provider’s continuation rate and its completion rate);

- Progression – the proportion of students progressing to managerial or professional employment, or further study – tells OfS whether a provider’s students have successful student outcomes beyond graduation. This used to include only higher level study, but will now include study in general.

We’ve covered this multiple times before – and it will be the source of much sector commentary – but before we go any further no, baseline rates for the above won’t be benchmarked for similar students and providers. OfS’ consistent line, maintained throughout, has been that it will focus on performance in absolute terms rather than in comparison with others through benchmarking:

All students are entitled to the same minimum level of quality. We do not accept that students from underrepresented groups should be expected to accept lower quality, including weaker outcomes, than other students. We therefore do not bake their disadvantage into the regulatory system by setting lower minimum requirements for providers that typically recruit these types of students.

For this reason, in assessing a provider’s performance OfS will focus on performance in absolute rather than benchmarked indicators – although it will take a provider’s context into account in reaching its judgement to ensure it has properly interpreted its absolute performance. More on that later.

48 varieties

Now you might be thinking “but surely the baselines OfS might expect might be different for different bits of our large and diverse university.” Well, OfS isn’t going to calculate those thresholds simplistically across all a university’s provision and nor will it only look at institutional averages. Quite the opposite. Instead, there will be baselines and performance rates for each of the three types of outcome for each mode of study and each level of study.

That means there will be separate indicators for full-time, part-time, and apprenticeships, and for the following levels of study:

Full-time and part-time modes:

- Other undergraduate

- First degree

- Undergraduate with postgraduate elements

- PGCE

- Postgraduate taught masters

- Other postgraduate

- Postgraduate research

Apprenticeships:

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

Yes, if you’ve been counting that means it’s perfectly possible for a large and diverse university to be looking at 48 different indicators.

But even if a university is doing well on them all, there would be a problem if students with particular characteristics were doing worse than others within any of them, which OfS puts as follows:

[our policy intent is ] to secure equality of opportunity between students from underrepresented groups and other students, before, during and beyond their time in higher education. This is because it will enable us to focus our attention on groups of students within providers that risk being left behind, even when the provider itself is generally delivering positive outcomes.

So OfS is also proposing to calculate performance on each of the 48 indicators using the following characteristics splits:

- Age on entry to higher education course

- Disability

- Ethnicity

- Sex

- Domicile

- Eligibility for free school meals at Key Stage 4 (for young undergraduate students)

- English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintile

- ABCS – OfS’ intersectional measure of underrepresentation (when looking at UGs only)

(Age and ethnicity will be disaggregated beyond simple binaries, but disability won’t be because OfS says that split indicators at this level would typically be too sparsely populated to allow consistent assessment).

Pick the pockets

And that’s not all. The statistical reality of provider level metrics regulation always meant that it might have been possible for a small provider teaching in a single subject area with 500 students to be refused registration on the basis of its outcomes, but for the same provision to go unnoticed if the same provision was buried in the averages of a 25,000 student provider.

So as well as all the above, we’re going to get splits at:

- Subject level (level 2 of the Common Aggregation Hierarchy is proposed)

- Course type

- Views of a provider’s student population

Subject level has been heavily and previously trailed as “pockets of poor performance” and is the area that will cause many sharp intakes of breath, given the wide variation in “performance” that provider-level averages currently hide.

Here “course type” will mean split indicators that look at full-time first degrees with an integrated foundation year separately from other full-time first degrees, others that look at Higher Technical Qualifications (HTQs) separately from other full-time first degrees, and another set that looks at level four and level five courses separately within the “other undergraduate” grouping.

Nowhere to hide (in Ilford)

But it’s views of a provider’s student population that is likely to prove most controversial. Here the proposal is to produce indicators for a provider based on the following student populations:

- The taught population with a further split between “taught and registered” and “taught only”, where the teaching is being done on behalf of another provider that registers those students, ie “subcontracted in”

- The taught or registered population all students registered or taught by the provider – this is the population it will use to set numerical thresholds, and performance will be further split by students both registered and taught by the provider, students taught by the provider on behalf of another provider ie “subcontracted in”, and students registered by the provider, but taught elsewhere by another provider, ie “subcontracted out”

- The partnership population all sub-contracted out students and those for whom the provider is acting in a validation-only capacity, again with a split to show registered only (students registered by the provider, taught elsewhere by another provider , ie subcontracted out) and validation only – students neither taught nor registered by the provider, but studying for an award of that provider.

Before you ask, yes OfS knows that that will all create additional burden and complexity (but it reckons it’s worth it), yes it knows that degree awarding bodies might be disincentivised from continuing or entering partnership arrangements if they were accountable for the student outcomes delivered by their partners, and yes it recognises that some providers fed back that a validating body’s role should be limited to oversight of the operation of a partnership arrangement and should not therefore have any accountability for the quality and outcomes delivered by its partners.

But OfS is having none of that:

We take the view that it is not appropriate for a lead provider to seek to generate income, or gain other benefits, through partnership arrangements while abrogating responsibility for the quality of those courses, including the outcomes they deliver. As with any regulatory intervention, we are required to act proportionately, and so would take into account the context of a particular partnership arrangement in our regulatory decisions.

That’s deeply uncomfortable for some, because it would appear that any number of small providers – often based in outer London, and often delivering health or business courses – used to be funded via HEFCE but have not since appeared on the OfS register, popping up instead within the franchise portfolio of a large university.

If there was a suspicion that those providers wouldn’t have had the outcomes to cut it on their own but are now burying their outcomes in a university, that place to hide is about to be removed.

That will doubtless cause a number of governing bodies to start ditching these otherwise profitable partnerships sharpish – but OfS has thought of that:

We do not expect a provider to ‘churn’ courses or partnerships to avoid regulatory attention. If there is evidence that a provider is withdrawing from partnerships to do this, we may undertake further investigation to confirm that its management and governance arrangements for its partnerships are robust and effective and that decisions to work with other organisations are the result of a strategic approach rather than opportunism. The outcomes of such an investigation could raise concerns about a provider’s suitability to continue to hold degree awarding powers that can be used in partnership arrangements.

The good news is that OfS will not prioritise assessment of a lead provider’s partnerships indicators in year one “to allow lead providers time to improve outcomes that appear to be below the numerical thresholds we set,” although how a year is long enough to turn around some of these mini-Titanics is anyone’s guess.

Frame it on the baseline

So as you can see, that’s a dazzling number of baselines, a spectacular array of splits and all sorts of ways that you can imagine the numbers will be wielded both internally and externally for accountability purposes. The next important issue, though, is what the baselines will be, and how OfS will use them to regulate.

On the first question, OfS is trying to prove to us that the baselines are a piece of arm’s length regulatory science rather than a piece of ministerial-behest political art, and that they are an objective (criterion referenced) measure of quality rather than a bunch of numbers designed to upset just the right sort and volume of people in the right sort of places (a kind of 3D norm referencing exercise).

Its strategy for trying to convince us of this conceit is a 35,250 word sub-consultation that describes the identification of a starting point for a numerical threshold using analysis of sector performance, the consideration of various policy and contextual factors, and then the setting of a final numerical threshold.

In the face of all the criticism about this approach and whether it represents a fair or meaningful and objective assessment, OfS has done that thing it always does – it doubles down, restates the argument and explains it even more slowly than previously, and in even more excruciating detail.

It’s a genuinely amazing couple of documents – unsurpassed classics of the genre – that have clearly been designed to be able to be waved in the face of a judge who might in the future be asked to rule on whether OfS’ approach is “rational”. DK has a separate, detailed and illuminating piece on it elsewhere on the site.

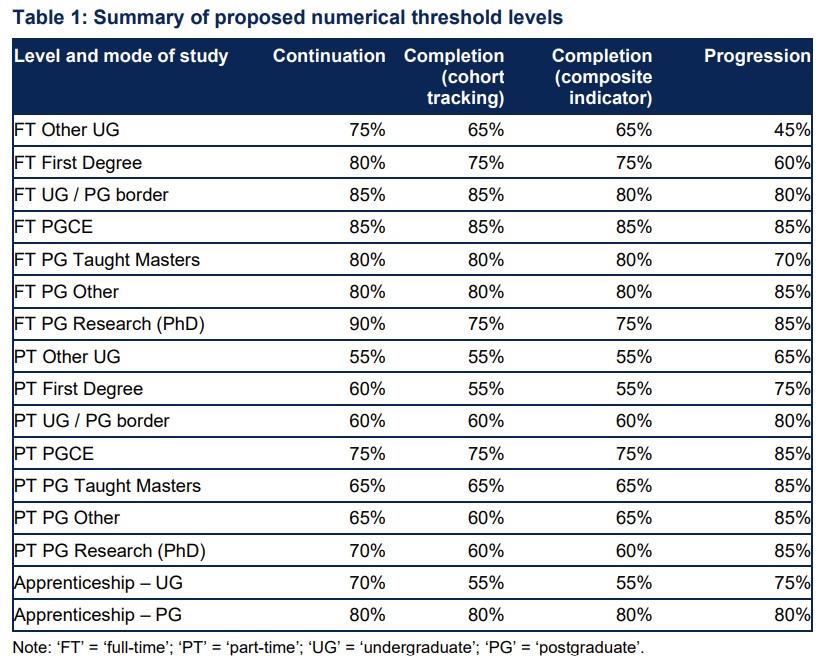

Here it’s the result we’re more interested in – and out of the other end of the machine, these are the baselines that will apply initially for the next four years:

These are not directly comparable to the baselines that OfS previously applied for a couple of reasons. The progression threshold, for example, used to be about professional/managerial employment or PG study, but is now widened to further study in general. And gone are the “not of concern”, “of concern” and “significant concern” bands that we had previously. That all amounts to both being a big tougher than before, and being able to look a lot tougher (having been asked to “toughen up” by ministers”).

I got my rock moves

Now you have to work out what to do with them. First of all, OfS is proposing to annually publish performance against all of these baselines (including split indicators) in a workbook, along with information about the statistical confidence it has in the numbers. It will:

- Publish the information via a dashboard on the website;

- Explore the possibility of linking the information directly to an individual provider’s entry on the register;

- Publish sector-wide data analysis on the website, and even

- Consider how to link to the information from Discover Uni to provide a route for interested students to understand the performance of individual providers in more depth.

And naturally, the compilers of other types of student information products will also be able to have a play.

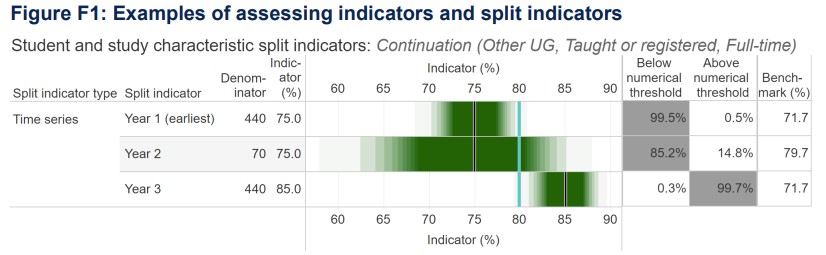

Here’s an example of some of the data you’ll be able to gorge on. There will be reams of this stuff – endless ways to stick the thermometer into the cake, all without knowing how the cooking works:

As ever, the mere act of publishing the data – given the way in which it will be used in relation to student choice, and the way it will impact things like performance assessments of managers or what the governing body might say to the senior team – will cause all sorts of internal accountability and action planning in the same way that the National Student Survey does now. It doesn’t take long to think about quite how profound an impact this could have on ramping up the sort of processes that already cause huge groans and grumbles across the sector.

In regulatory terms, OfS isn’t proposing to chuck every provider off the register off the back of any of the indicators failing their benchmark either in absolute terms or in any of the splits. That’s partly because the proposed approach “will generate a very large number of indicators and split indicators across registered providers,” and partly because “even a provider that is generally performing above numerical thresholds may have small pockets of provision that are below a threshold.”.

So given OfS is a risk-based regulator, it won’t assess every possible instance of non-compliance with condition B3. What it will do is adopt a “prioritisation approach” to identifying the providers for which it will assess compliance each year:

- It could take a thematic approach, for example identifying areas of provision where it has a particular concern about outcomes across the sector. This might include, for example, part-time students on other undergraduate courses, or courses of all types in a particular subject, or outcomes for disabled students. Whatever ministers are exercised about this week, in other words.

- It could prioritise providers where performance in relation to numerical thresholds suggests that there may be the most severe breaches.

- It could prioritise providers where performance in relation to numerical thresholds suggests that there may be breaches relating to particular groups of students.

- It could prioritise providers for which it has the strongest statistical confidence that performance is below a numerical threshold.

- It could randomly select providers with indicators below a relevant numerical threshold.

- It could be given a list of providers by Michelle Donelan whose VCs were mean when she did a ring round about in-person teaching.

I made the last one up. Or did I?

Or blow me a kiss and that’s lucky too

Whichever approach it uses, there’s then a process where it carries out a detailed assessment of a provider (with all sorts of interesting bits like giving providers a positive benefit of the doubt where there’s gaps in the data due to low numbers of students) and the use of contextual factors.

These are proposed as:

- a) factors that are relevant to understanding the reasons for a provider’s historical performance, and

- b) actions a provider has taken, or will take, to improve its performance and the extent to which those actions appear credible and sustainable.

The first of those – the “looking back” factors – will include performance in relation to benchmark values, external factors that OfS considers to be outside a provider’s control (ie the pandemic), or evidence of particular course or profession attributes that are features for that provider and result in outcomes consistently below a numerical threshold but that otherwise would be considered positive outcomes.

This is what I’m calling the Mary Poppins clause – named after Norland College, the provider that trains posh nannies whose graduates are thrilled in the graduate outcomes survey but whose jobs aren’t classified as graduate jobs.

The second – the “future” factors – is OfS giving consideration to factors where a provider can evidence the impact of actions it has taken or is planning to take to improve its student outcomes.

In other words, once OfS identifies provision that’s below its thresholds, it works out if there’s a decent contextual reason for that, and if the provider already has stuff in place to turn it around if OfS thinks it needs to. It turns out that there’s subjectivity and qualitative assessment in the objective quantitative assessment after all – or put another way, there’s endless “get out of jail free” cards for OfS to be able to use when someone spots any quirks and unintended consequences that this kind of process might throw up.

It’s all very “damn everyone quantitatively” and then “let some off qualitatively” rather than “don’t use the anomalies and the special cases to allow bad outcomes to slip through the net” – which conveniently allows OfS to plough on and then say that any foibles or practical inconsistencies in the model, or local campaigns led by MPs to “save our college HE provision”, or colossal anomalies like the OU were always going to be fine after all. Probably. Maybe?

And then once all that’s done, it has the usual regulatory tools at its disposal – letters, conditions of registration, and yes technically even those £500,000 fines and the threat of deregistration.

It’s all coming up

This is technically still a consultation – although it’s on a tight timeframe, given OfS wants the new regime in place for the new year partly so that it can issue another press release that generates another £500,000 fines for Mickey Mouse courses headline.

That tight timeframe is the thing that will cause much consternation. Once you get your dashboard, almost everyone is going to have to some bits that are below threshold – and for each LED that’s flashing red, that generates four major choices for universities:

- You can ignore it because you reckon you can front out contextual reasons, or because it’s an outlier that might not be in a big theme this year;

- You work to actually improve the continuation, completion or progression scores – although there’s necessarily a long lead time on making a difference;

- You change the students you recruit by taking fewer risks on otherwise contextually talented students – focusing on the social backgrounds more likely to stay the course and have the family connections to get a graduate job;

- You slowly, quietly, carefully exit this provision. “It’s not one of our strengths” or whatever, and anyway the costs are high and recruitment is poor and…

What universities will do in response to those dashboards both in September and in the nervous run up to it could probably fill a thesis on regulatory design and game theory – but my own view is that when you have 151,689 words on the design of this thing, and zero words on why students drop out and why they’re not getting graduate jobs (and what therefore universities might do about it), we may not end up with the focus on “improvement” that OfS professes to want.

And then there’s the question of mutant cats out of multiple bags. Even if OfS is officially focused on improvement, just look at the way that ministers have weaponised the experimental OfS “Proceed” measure (which multiples completion with the graduate jobs measure) in speeches and pronouncements. Imagine what think tanks, commentators, front benchers and backbenchers are going to do with your dashboard – where every university is harbouring a festering pocket of paid for provision that taxpayers and students should be saved from subsidising.

And with holes in the dataset on DiscoverUni and English ministers being able to interrogate previously impenetrable institutional averages to find pockets of poor outcomes, don’t bet that ministers in the devolved nations will be able to resist copying the approach for long.

For DfE and the Treasury, the temptation (and pressure) to link “what we fund as a government” to these scores will be absolutely overwhelming – and if anything, the triumph in the documents would have been the sophistication with which OfS pretends that this isn’t what all of this is ultimately designed for, were it not for the fact that OfS has overcooked it a little bit.

Take a chance on me

But as well as all of the above, what worries me most about these proposals is how the sector will respond. As I said above, the now almost cliched response to absolute outcomes baselines will be a timeline of takes that points out that contextual factors impact the outcomes, that universities aren’t in full control of them, and that they ignore the value added.

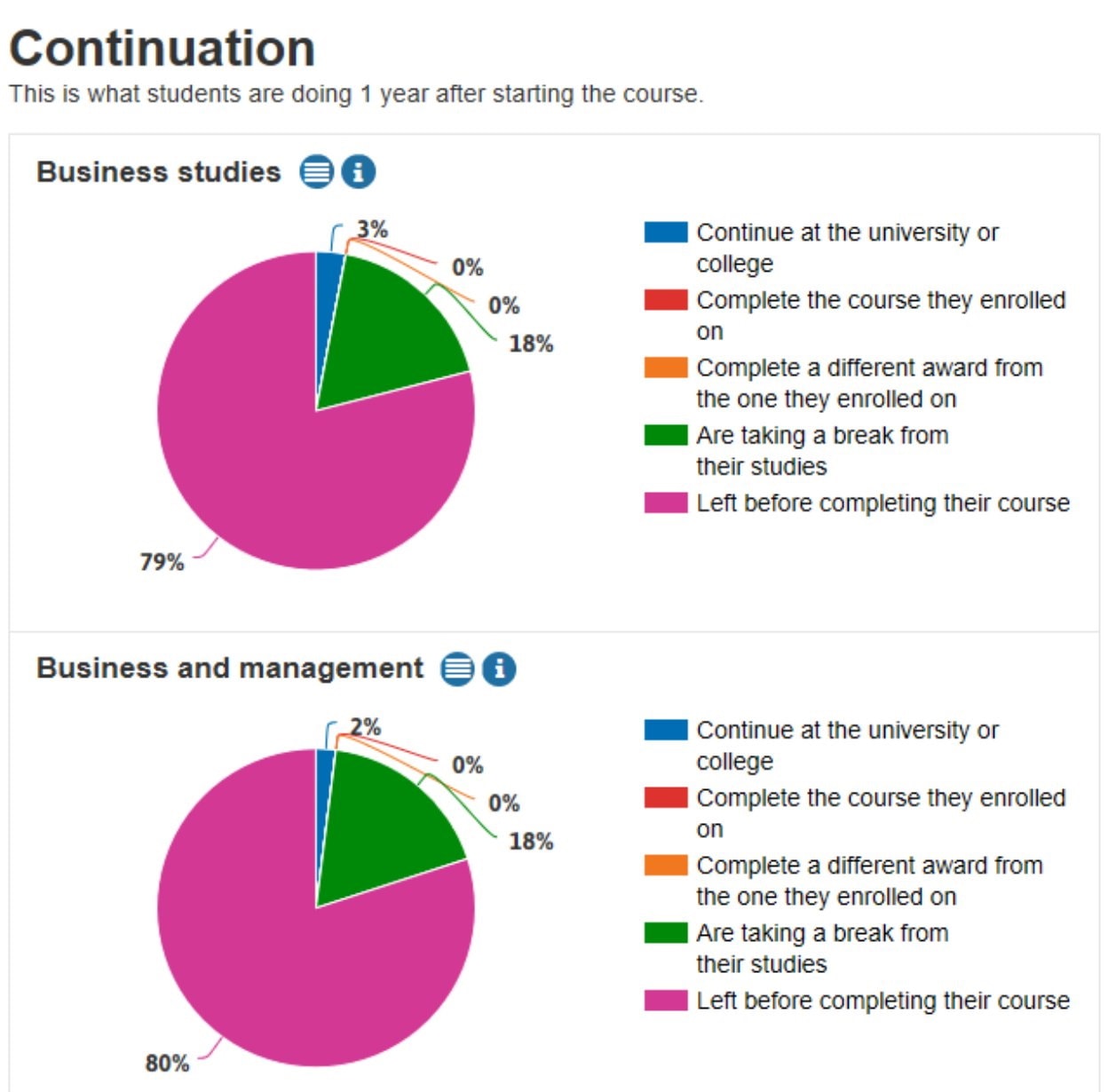

Tweet away lads, but those arguments won’t work – partly because ministers and their advisors will point out that if education can’t influence the outcomes, why bother with it – and partly because courses like this just look like terrible value both for the students enrolled on them and the taxpayers subsidising them:

What matters for me is risk, and the impact on students when we decide that some risk can’t be mitigated. Once we have outcomes analysis at this kind of level, for example, there will be strong and powerful incentives on anyone responsible for recruitment at any of the levels of granularity on offer here to take fewer risks on “contextually” talented students. OfS is almost totally silent on that prospect, and nor is there any sense that its main balancing mitigation strategy – its access and participation regime – will operate at this level.

Even if that wasn’t a risk, in the Blair/Barber world of public service providers and performance metrics that this whole thing is a dated product of, once a provider winds down the course or a regulator defines a set of outcomes as unacceptable, things only work out if students can exercise choice, or go to another provider with better outcomes, or end up being happier with a different kind of education because we’ve decided it’s “right for them”.

At the first meeting of West Herts College’s board that I attended in 2009, faced with a set of outcomes for our A level students (who wanted to do something academic but had been failed by their school system), we were directed to face down the loyal and talented staff teaching those courses and drop and teach-out the provision, because there were other courses that were “better” for these learners that had better outcomes.

And maybe it’s the case that these students with a passion for History and English and Economics were happier doing hairdressing, or found another college just outside of West Hertfordshire where they could pursue their dream. Maybe that dream was faulty and we were wasting their time. Or maybe we’d decided that we just weren’t prepared to take the risk – on them.

Who we decide to take that kind of risk on, and who we decide to withdraw that sort of opportunity from, is one of the most profoundly political decisions that anyone can make. It’s a decision that pretends to be about provision, but is really a decision about the students who try to enrol on it. It will all have deep and scarring impacts across large parts of the country, and will be hugely unfair on those students who can’t move around to exercise “choice”.

And as such, despite the 151,689 words, I’m not at all sure that OfS has fully understood just how far from objectively and scientifically neutral this set of proposals will put it.

Great article Jim. Not 151k words thankfully. At the heart of all of this posturing from Govt. is a denial of learning opportunities for those with more convoluted journeys. Feels like we are returning to elite forms of HE when the working classes knew their place and went into semi-skilled work not education if they were ‘bright’. As you suggest, providers will inevitably game who they recruit to almost guarantee meeting these outcomes. Shocking way to hurtle back to the age of Mrs Miniver.

Agree fully with with Stella Jones-Devitt here – the proposals to remove benchmarking (and introduce absolute measures) are likely to impact most on universities who accept a wider range of students. It is likely these providers will either need to invest more in ‘value added’ activities and support (with the associated long lead times), or they will – well – just need to be careful about recruiting too many ‘resource hungry’ students. A Hobson’s choice that will impact on institutions committed to serving and levelling up in local communities and economies. The elephant in the room remains: how do you… Read more »

Great article. Disturbing how these proposals have the potential to destroy equitable access to higher education.

Hi Jim. This is a really important article and there is so much I want to say but I now realise it would be a detailed and effortful waste of time when I could say just as easily “the proposals are dire”. For me, the idea of the modern university, an epistemological one btw, is being damaged more than ever both internally and externally. To me the proposal is like an ant colony utopia where HE is the single point of blame when the ants don’t do what they are expected to do. Solution: lets just be elitist institutions again… Read more »

Hi all, hoping you can clarify my mis/understanding. The document (and great article above) mention a possible 48 indicators, but then goes on to say there will be further splits by characteristic for EACH of those 48 indicators. Does this mean that providers will actually end up with the potential for a few hundred indicators?! Thanks!

The bigger question for me is how will Universities be able to afford to run the more costly ‘real science’ lab based courses without the lessor student ‘Mickey Mouse’ course fee’s topping them up? The government doesn’t give a ‘Donald Duck’ about funding the more costly courses, and it’s hunts for ‘Mickey Mouse’ courses will likely be more like ‘Elmer PhD’ pursuing ‘Daffy Duck’, with many academic ‘former drips under pressure’ employed as CONsultants costing more than the savings made, whilst the students on ‘Mickey Mouse’ courses won’t have their lifetime debts ‘Minnie Mouse’d’.

Great puns Neil :0

Michael

48 indicators and threshold targets(see the table above), but lots of ways of doing split results of those 48…

Ofs – ted. just saying

And of course this all continues the march away from peer review in assessing academic quality and standards. Ultimately the judgments are subjective and qualitative (fair enough; quant data usually tells you what you need to think about, rather than doing that thinking for you). And those judgments are made by OfS with little or no apparent involvement from academic peers (either with/through the involvement of QAA as Designated Quality Body, or some other route). Essentially almost all elements of external peer review have been removed by OfS (e.g. the way that the guidance on Conditions B2, B4 and B5… Read more »

Rates of continuation and the percentage of students completing a course will be based on numeric facts. There is not much a University can do about this once a cohort of students has started. The area for creative thinking is “Progression – the proportion of students progressing to managerial or professional employment, or further study – tells OfS whether a provider’s students have successful student outcomes beyond graduation. This used to include only higher level study, but will now include study in general.” The definitions of “managerial” and “professional” are open to wide interpretation – a prospective apprentice described his… Read more »