Everyone has a hobby.

My father-in-law is big into model railways, trundling his layout around the exhibitions of the South East. Some treasure their football programmes, or collect Panini football stickers. Clive Evenden collects monopoly sets.

I remember Eastenders’ Dr Legg collected butterflies. My auntie used to collect stamps. My cousin was trying to collect every single produced by Stock, Aitken and Waterman – and I was very jealous.

For my own part, as well as nurturing my collection of recordings of 1990s radio jingles (principally from the West Midlands), I collect the manifestos (and single transferable count sheets) of students’ union officer elections, going back quite a few years now.

I promise it’s a more interesting archive than it sounds. It’s like a social history of the sector, youth politics and fonts – and you track both the student issues (and framing of them) of the day and the issues that the sector never seems to be able to solve.

The best and most relevant manifesto doesn’t always win, of course, but when I think about the issues that students’ union officers care about, and the issues that universities care about, I tend to think of a sweet spot on the Venn diagram where issues apparently matter to both.

One of the grand ironies of having an “Office for Students” in England is that said sweet spot feels like it’s been getting smaller in recent years.

Not only does the regulator have a tendency to focus on things that seem more important to ministers and the Sunday Telegraph than to students, even when the interests overlap, the language seems to differ.

Sometimes an issue will be a shared concern but SU officers tell me that a university will only go as far as the regulator tells the university to when fixing it.

This has all been particularly true when it comes to access and participation. Given what’s been in those manifestos over the years, students’ unions ought to have been all over the “getting on” bit of the equation as it has developed – but it never seems to have caught the imagination of those that represent students.

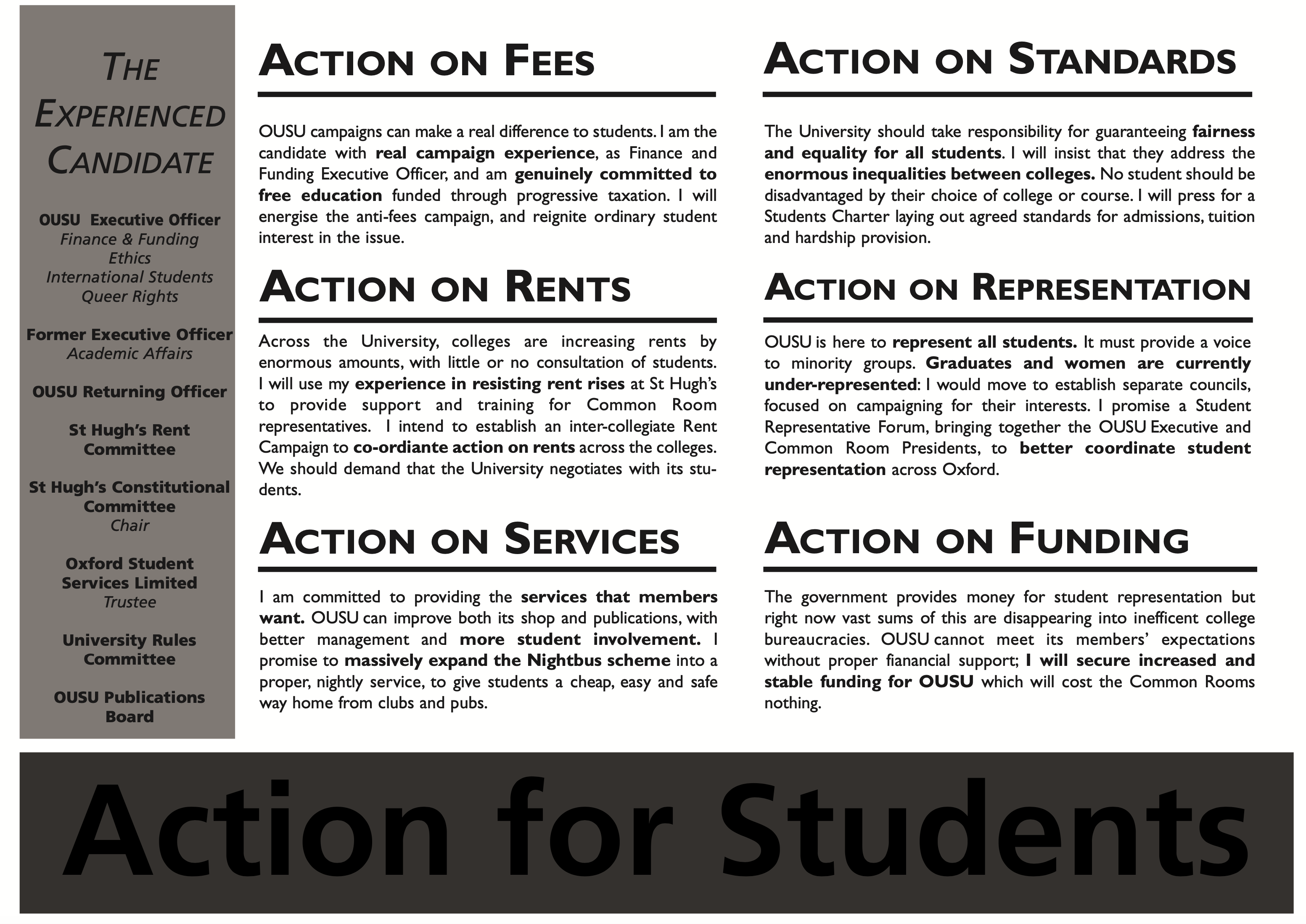

So after a weekend in the attic hunting, I thought I’d compare the concerns of John Blake, the winner of the 2004-05 Oxford University Students Union President election with those of John Blake, the 2023 Office for Students Director for Fair Access and Participation.

And it’s made me look at his new Equality of Opportunity Risk Register in a whole new light.

Open letter

Back in 2021, two of the year’s most talented student leaders – Jaudat Alogba from Middlesex and Patrick O’Donnell from York – wrote to John Blake to press home the importance of considering the wider student experience.

Their point was both that access to extracurricular activities is uneven, and that there is strong evidence to suggest that participation in them can impact students’ chances of reaching year two, completing the course, and getting a graduate job.

But banging the drum for a consideration of the wider student experience in access and participation policy has felt like a hard slog over the years.

OfS has lurched from disavowing itself of the importance of community and belonging in its survey work, to asserting that extracurriculars and student welfare shouldn’t be considered in the TEF, to reminding anyone that will listen that it doesn’t regulate student housing, through to tepid interventions on cost of living.

So the good news is that the Equality of Opportunity Risk Register, which providers will both have to take account of and develop a version of locally, is actually chock-full of understanding of the impact that such matters can have on getting on.

2004 John Blake was worried about rents on campus. 2023 John Blake is worried that “where appropriate student accommodation is limited, students with less money or who are accepted at a late stage in the application cycle may not be able to secure suitable housing.”

Noughties John Blake wanted agreed standards for hardship provision across the Oxford colleges. Today he’s worried that “increasing costs of living, if not adequately addressed, may result in an increasing number of students undertaking part-time or full-time employment alongside their studies, poorer mental and physical health for students, reduced attendance on-course, and less time to study” – all of which may “increase the risk of lower on-course attainment rates and lower continuation rates.”

Twenty years ago Blake wanted to expand the night bus service and ensure standards for academic support and tuition – today he’s worried that students may not receive “sufficient personalised academic support to achieve a positive outcome”, concerned about personal support in many forms (including “from personal tutors or mentors to access to sports facilities or accommodation support”) and is concerned that students “may not experience an environment that is conducive to good mental health and wellbeing.”

The point is that for pretty much the first time, OfS’ participation work under Blake is finally recognising that it’s not just the course per se that can impact your outcomes – it’s also the environment, the services, the opportunities and the community that work against the metrics.

I might be galled that the EORR recognises that lower wellbeing and/or sense of belonging can be an issue and then points to NSS 21 as evidence given the regulator is scrapping the question, but at least the recognition is there.

Sweet spot

Part of the reason that this is so exciting is that the sort of people that tend to toddle along to the Secret Life of Students when we stage it are the sort of people that worry a lot about all of this stuff.

They know all about the relationship between belonging and retention for some students, or the impact that waiting months for a counselling appointment can have on those who need it, or the way in which having to live further out because you don’t have the choice of housing can shape the experience of those more likely to enter via clearing.

But whether they’re SU types or student experience staff in universities, lots of them suggest to us that there is an increasing tendency to take the student interest into account only in restricted circumstances – when it happens to have been incorporated into a regulatory advice note or is something that has popped up in an OfS press note.

Worse, there’s evidence of tickboxery, puppeteering and hand-picking input designed to praise rather than scrutinise, and dismissing the impact of growing too quickly or not having access to wellbeing support as the concern of some other committee.

So what’s great news here is not just that having both listened and looked at the evidence, Blake is so keen to see concern for getting in and getting on embedded properly in provider’s culture – it’s also that providers and their student representatives (at all levels) will have to work closer than ever to do so.

It’s likely to mean successful providers will be the ones building the capacity of representatives to understand and reflect, gather and synthesise evidence on APP work. They’ll be the ones listening to the independent student reps in front of them, acting on their feedback and supporting students to develop their own interventions along the way. And they’ll be reviewing their rep systems too.

Plonking a single bewildered student rep on a committee and asking them to sign off on an APP at the last minute, only to then complain to evaluation teams that student reps are hard to work with because they often change is the ultimate example of the kind of cheat code Blake wants deleted.

Working with students’ unions reps and staff, along with student experience teams, to embed a deeper culture of student engagement at every level – on everything from getting data sharing right, to showing the impact of extracurriculars on the underrepresented, to building the group capacity of those who are the target of APPs to issue meaningful challenge on initiatives designed to help them, will now be the right way forward when taking Action for Students.

And the prize for best wonkhe article header image goes to…