As universities put finishing touches to their headline plans for the autumn term in pursuit of the usual “absolute clarity”, I have a scenario I feel the need to share.

If we are not careful – taking collective steps to avoid disaster – there is a realistic prospect that the term will be miserable for students and the staff that support them, and that we will make most of the mistakes that we made last summer as a sector all over again.

What’s got me there is something I’ve been repeatedly forgetting about this pandemic thing – that there isn’t going to be some magic moment of normality when this is all over. The best bet remains that things will eventually settle at “not as bad as they were”, but still “really bloody uncomfortable” – with both minor and major lurches back until there is widespread immunity in the population.

I’m also reminded of how profoundly incompatible several features of the UK’s higher education system are with a pandemic involving a deadly airborne virus.

And with that in mind, having elsewhere sounded notes of caution about restrictions to in-person interaction, I thought I should set out a plausible scenario where restrictions are still very much on the cards.

Do you remember

It’s September. Clearing has gone “well” from a “what you tell governors headline figures” point of view, but you know that under that surface there’s departmental level under and over recruitment that will have to be painfully reconciled later in the year.

All summer, and during clearing, you were doing what your legal advice told you you had to do, and you advised students about your “blended” and “hybrid” teaching and learning offer – which is really running lectures online and surrounding that basic decision with mood music about technology and flexibility.

Because nobody locally or nationally stepped in to stop it, the default assumption – that students must be resident in the town or city where their university course is based – is already a runaway train. Contracts are signed. Move-in days are fixed up.

The looming problem is vaccination. Not nearly enough of them have been double-vaxxed, and a sizeable enough minority refused to get the vaccine when offered. Many were caught up in GP/inter-UK chaos and now don’t know where they need to be for jab number 2. International students are entitled to the vaccine, but you can’t double-vax people in a week. And neither feeder countries nor any of the UK’s countries have said “let’s move students up the list” for either of the two jabs required.

Much of student “life” in the UK involves intensively “sweating” indoor spaces that double as great places for students to mix and build a network – nightclubs, lecture theatres and hotel-style halls all spring to mind. The research from Cambridge told us that there wasn’t really transmission in lecture theatres last year (because they were operating at 30 per cent capacity if at all) but there was in clubs and halls. Well you don’t say.

You’ve already made plans to restrict your campus in broadly the same way you did in autumn 2020. You’ve therefore already not warned students about the impact that will have on their overall academic experience – because to admit that missing out on hanging out in queues and libraries and social learning spaces is a problem would be to admit to returners and graduates that they did miss out last year after all.

In wider society, despite a wobble in June, nightclubs are not closed and hotels are not shut. Neither involve lots of mixing just prior to being present and just afterwards, neither are really designed for or involve large scale network building, and neither involve lots of large intensive group mixing afterwards.

But because of the vaccination programme progress and the issues with international arrivals, and the specific risks when students use these sorts of spaces – the scientifically demonstrated risks – steps have to be taken. Levers are pulled, rules are invented. This is an airborne virus where mingling indoors must be reduced. So one way or another, it is. And so because you can’t send them home, students, again, spend most of each week alone. In their room.

I pine a lot, I find the lot

It’s mid-November. We’re now eight weeks into our blended, “socially distanced”, “Covid-secure”, “dual delivery” term.

It’s cold. It’s dark. It’s raining. And students are loudly and angrily vocalising to the press, the public and their parents what we really ought to have predicted – that their experience of higher education this term is turning out to be unremittingly miserable. Again.

Campus is eerie and quiet. Between classes, students aren’t really allowed to be on campus. In September freshers were playing rounders and chatting in marquees, but it’s bitterly cold now. What indoor social space there was has either been converted to teaching, or is running at 30 per cent capacity. So partly to get home in time for the next Zoom lecture, and partly to see their friends, they flee campus as soon as possible.

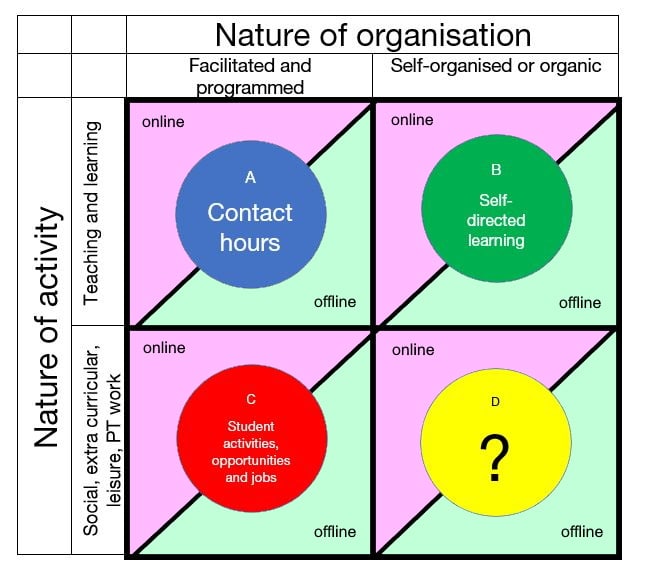

And there’s where the problems really compound. Independent study – in groups, in labs, in studios, in corners – makes up a huge chunk of a given student’s week, and much of it used to happen on campus. But there’s no space to study on campus. For all of our reliance on it when we were being harangued over contact hours, we didn’t allocate any campus capacity for it for this term. We forgot. Again.

Commuter students no longer have campus to “escape” to – and find it impossible to progress with the pressures at home. Those on the wrong side of the digital divide are robbed of the facilities on campus that enabled them to succeed, and hardship funds to cover the issue won’t stretch as far as ministers pretend.

Meanwhile “traditional” residential students that aren’t yet double vaxxed still mix and spread the virus like wildfire, indoors. Because of course they will. Because while we timetabled Lecture Theatre 3 on thirteen different scenarios, we forgot to work out what students would be doing with their lives. Because we never asked. And so we locked them down and hit their mental health hard. Again.

And meanwhile, staff are exhausted. The obsession in No.10 with only acting at the last minute (after all, it might not end up as bad as you fear) is still trickling down, and causing that quintessential enemy of learning – disruption. Constant, grinding, exhausting disruption.

It’s disruption that started with intense meetings in March 2020 about the emergency online pivot. It’s disruption that continued all year with unrealistic working groups about teaching spaces and timetabling and course rewrites something someone called “hyflex”. It’s overlaid with a belief that messages of gratitude, optimism and guidance compliance will ensure you end up in The Good Place.

Now there’s been time to actually evaluate the impact, you know it’s disruption that hit students in access and participation categories hardest – and makes the already precarious situation facing parents or those with wider employment or caring commitments throw their hands in the air with frustration.

It’s the unending, relentless, maddening disruption of it all – never giving ourselves the time to breathe, or plan, or think through the implications – glued to the rank futility of doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result.

Avoiding the disaster

Won’t we just be told to “live with the virus”? Maybe. It’s a better bet that that’s a plausible statement for a politician to utter once everyone’s had the chance to be double vaxxed. And not before.

I’m not sure the scenario as described will come to pass and nor am I optimistic about avoiding its negative impacts if it does. But I do think there are reasonable steps that can be taken by governments and universities to mitigate against some of the worst aspects of it.

The first and most important thing to do would be to get an understanding of students’ lives into the decision making meetings. It’s not so much that X or Y needs to be online or in-person, it’s that any university taking seriously the idea of being student centred should have a decent understanding of what an average week should be like for a student both when it makes its own decisions and when it’s feeding into others’.

My best example of “wrong end of the telescope” thinking is where we tell students about lectures being online but we don’t paint the picture of what restrictions will do to their lives overall. The question should be “what do we want their experience to be like” or “what will their experience be like”, not “what bits of what we formally organise do we need to formally warn people about.”

So next, we should warn students. I don’t mean sprinkling positivity dust on moving lectures online – I mean making clear to students that it is entirely possible that the realities of the pandemic will mean heavily restricted self-directed campus learning interaction, social interaction and living interaction. Or put another way – as long as it’s still deemed dangerous to have students mixing in lecture theatres is as long as we should be delaying the September migration.

Where a student is warned and pausing for a year would be difficult, there should be national lobbying and campaigning to make it less so.

Many will say to me “well Jim, we can’t do all this” or “that will put them off” and maybe that’s true. But it’s the morally right thing to do. And governments that have the higher education system that they have, with all of its existing features, could be given two choices – fewer students go this September, or the usual number go with a government prioritisation of steps and investment to ameliorate the risks.

Ultimatum

When you assess risk you should take steps to mitigate against it. That could and should mean a delay to the start of term until everyone’s had the chance to be double vaxxed, earlier guidance, prioritising students and staff for vaccination, investing in the sort of testing, tracing and isolation support we saw possible in Cambridge, or underwriting students’ ability to change their mind if it doesn’t pan out.

It might mean setting out a plan for higher education in the next two weeks, like is about to happen in the Republic of Ireland.

We should also be honest about consumer protection law. As drafted, in this situation universities can’t be meaningfully compliant. And they’re getting away with that because of weak enforcement. You might not like the consumer framing, but if we can’t keep basic promises to students about what we’ll do and how we’ll do it, we ought to have a way as a society to protect and insure the people that are therefore taking those risks – not building incentives to hide them during clearing.

The point I’m making is that September brings risks. If handled well, the sector and governments can act now to make sure that those risks aren’t all shouldered by students themselves again. If last September’s examnishambles tells us anything, it’s that for all the talk of alternatives to university, all four governments need this sector to keep the university places show on the road. With road conditions this precarious, the sector owes those that will be paying for it all their lives a seatbelt.