In the public discourse, it’s taken for granted that a university education should equip students with something “beyond” subject knowledge – you can call it skills, capabilities, competencies, literacies, dispositions, behaviours, mindsets, or attributes, or some of these in combination – that captures the essence of graduateness.

This assumption recognises the reality that as the world and the state of knowledge and practice change, specific subject knowledge, especially technical knowledge, may quickly become redundant. Knowledge as arranged in the academic disciplines does not neatly overlap with knowledge and practice as it is arranged in the graduate labour market.

Students are undoubtedly graduating into a fast moving world, one which will demand a lot of cognitive input and in which “success” – perhaps best defined as the capacity to live a life that has meaning to you – depends on a complex mix of skills, attributes and behaviours. Employers, too, are demanding an increasingly wide range of hard and soft skills, presenting a challenge for universities in how best to support student skills development.

An essential strength of higher education is the development of critical citizens equipped with the ability to question, learn, and innovate, working beyond the straightforward ability to replicate established ways of doing things, to bring creative approaches to solving complex problems.

Though some of the policy language and metrics around skills and graduate employability can be rather reductive, academics and employability practitioners continue to develop increasingly sophisticated ways to think about student academic, personal, and professional development.

We hoped to understand more about thinking on student skills development from the perspective of the people who arguably are the closest to the challenge – academics, and those in academic-related roles such as careers advising, education development, and learning technology.

The Skills to Thrive research

In the autumn of 2020 Adobe and Wonkhe partnered in a small-scale survey to gain insight into how academics and those in academic-related roles with responsibility for curriculum and student development are thinking about skills and specifically, which are the priority areas, where the responsibilities lie and the extent to which work in this area is subject to monitoring and evaluation.

We caveated our survey with the acknowledgement that everything we know about skills development suggests that there is no such thing as a skill practised in the abstract – skills are grounded in academic and professional knowledge.

Our sample was healthy (particularly given the context of Covid-19), with 826 respondents of which the majority (87.5 per cent) were based at an institution in England. 44.8 per cent worked in pre-92 universities, and 42.8 per cent in modern universities, with the remainder based in specialist, independent and further education providers. 15.6 per cent were academics in the sciences – including medicine, health, engineering and physical, computing and mathematical sciences. 36 per cent were from an arts, humanities or social sciences subject. 48.4 per cent worked in academic-adjacent roles such as education or learning development, learning technology, library services or careers.

The disposition of respondents is illustrated in that 87.3 per cent responded that soft skills are “very valuable” in preparing students for their future lives, and a further 11.7 per cent said they are valuable “in some circumstances/with caveats”, suggesting that respondents who engaged with the survey did so because it is an issue that is important to them. As such, the findings may not represent an endorsement of soft skills development among academics in general.

We chose to use the language of skills as being widely understood, and adopted “soft” as a way of articulating the kind of skills we had in mind. Understandably though, especially among respondents who had spent their professional lives thinking about student development, this was seen as unforgivably under-nuanced – and some felt strongly that “soft” implies denigration (which was obviously not our intention and indeed, a learning point for us).

The debate over the language used in student development, and the depth of feeling expressed, suggests that student skills development remains a contested area in universities, and something that is a source of possible tension – whether productive or otherwise.

Essential skills

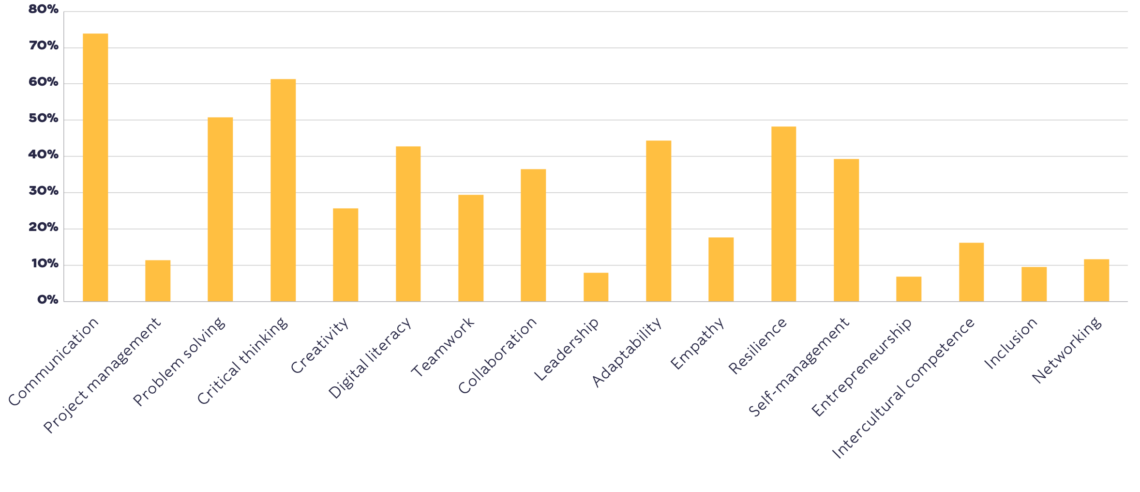

We wanted to find out which skills respondents consider absolutely essential for students to thrive in their future lives, offered a curated list of recognised skills areas (accepting that it would be impossible to produce a comprehensive list), and asked respondents to select up to five.

The skills selected by the largest number of respondents were, in order of priority:

- Communication

- Critical thinking

- Problem solving

- Resilience

- Adaptability

- Digital literacy

“Communication” tends to score highly in all such lists, given its universal importance in being able to function at all in the world – and inevitably encompasses a very wide range of practices that are likely to be filtered through particular professional cultures. The breadth of endorsement of the necessity of communication skills suggests the importance of breaking down what this means in different contexts and supporting students to develop the specific types of communication skills that will help them achieve their aspirations.

Problem solving and critical thinking speak broadly to cognitive-academic skills, and adaptability and resilience to the challenges and complexities facing students after graduation. Digital literacy acknowledges the infusion of technology into all our lives, and the necessity of equipping students with the knowhow to use digital tools to underpin and enable the practice of all the other skills.

Essential skills split by subject/professional grouping

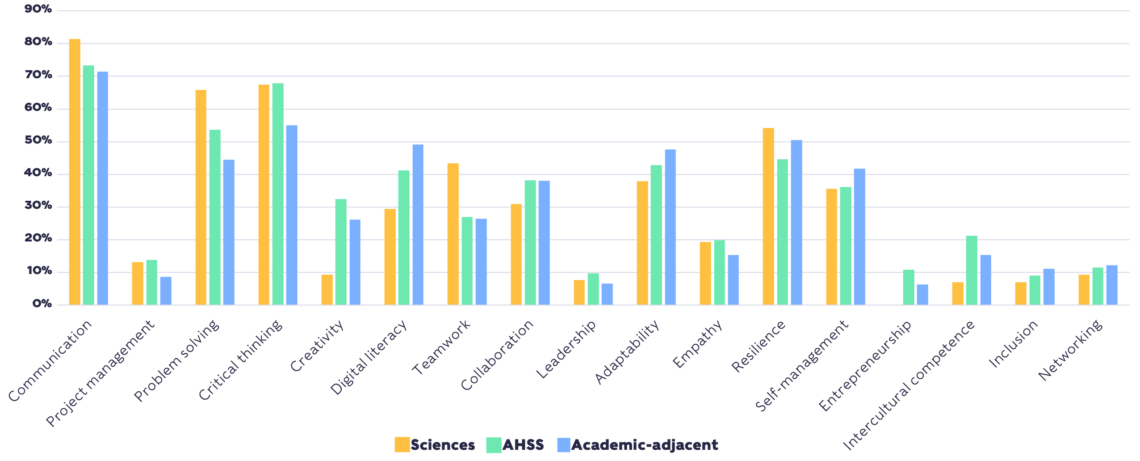

We compared the answers to the question on essential skills by whether the respondent had identified as an academic in the sciences (129 respondents), an academic in social sciences, arts and humanities (296 respondents), or a professional working in an academic-adjacent role (378 respondents).

We did not find any difference in the six skills areas identified as the most important, but there was some variation in the proportions of each group who listed particular skills as essential. Among the six most essential skills areas, respondents from the sciences were slightly more likely to prioritise communication, problem solving and resilience, while academic-adjacent professionals were more likely to prioritise adaptability and digital literacy.

Among the other listed skills respondents in the sciences put a higher value on teamwork than respondents from the other groups; and respondents from arts, humanities and social sciences, and academic-adjacent professionals put a higher value on creativity than respondents in the sciences.

Missing from the list of essential skills

We also asked whether we had missed any skills from our list that respondents considered essential. The responses were fascinating in that they paint a collective picture of how respondents perceive “graduateness” – but it’s worth noting that the individual who embodied all these qualities (or the course that produced them) would be exceptional indeed.

The largest number of comments related to a theme of personal agency – which comes across as a not always very definable ability to make things happen, or make an impact. Suggestions we filed under this category include: being enterprising, pitching ideas, confidence, initiative, self-belief, work ethic, determination, influencing, independent, resourceful, able to ask for help, proactive, decision-making skills, a “can-do” attitude, and (arguably) “health and wellbeing skills”.

Other categories that emerged from the suggestions were:

Emotional and interpersonal: The ability to build relationships, engage in dialogue, manage conflict, and manage people, including qualities like kindness, patience, the ability to listen, trust, respect, honesty, fairness, and friendliness.

Cognitive/academic: The development of independent learners, capturing skills like analysis, synthesis, “thinking”, numerical, statistical and information literacy, reading quickly, identifying salient points, writing, research, and “framing powerful questions”.

Self-awareness: The ability to know one’s own strengths and limitations, reflect on experience, act on feedback, and articulate one’s skills.

Context awareness and sensitivity: An ability to situate one’s own experience in a wider context, most frequently referenced as commercial and industry awareness, but also including cultural context, political awareness, global awareness, historical, aesthetic, and a general sense of the bigger picture.

Practical and professional: Mastery of bread and butter but essential practices such as time management, professional etiquette, facilitating meetings, “understanding and reading regulations”, form-filling and administration, being organised, and financial literacy.

Ethics: including sustainability, “ethical citizenship”, academic integrity, business and professional ethics, anti racism and social justice.

Responsibility for supporting student skills development

Student skills development is clearly the responsibility of the whole university, as well as being one of those areas where students themselves need to actively engage if they’re going to benefit from the opportunities available.

But “whole university” responsibility can sometimes translate into “nobody in particular”. One respondent helpfully articulated this issue:

I’ve worked in a few different universities and at each, there has been a recognition that the university could, and should, do more to support students to develop these skills, but there never seems to be agreement on who should take responsibility. There are pockets of expertise in different places, and as a result this tends to be approached in a piecemeal way.

So we wanted to find out where our respondents felt the primary responsibility for different aspects of skills development sits within the university ecosystem. In order to ascertain this we offered respondents five different aspects of student skills development and a range of potential actors including individual academics, course or programme teams, academic departments or faculties, professional or student services, individual students, the students’ union or an external organisation.

| Where does primary responsibility lie for ensuring that... | Course/programme teams | Academic departments and faculties | Professional and student services | Other (individual academics, students, SUs, external organisation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students understand the soft skills they could/should be acquiring during their time at university | 49.60% | 27% | 9.90% | 13.50% |

| Students understand what activities and experiences will help them develop those skills | 42% | 18.10% | 21% | 18.90% |

| Students have access to activities and experiences that will help them develop soft skills | 30.90% | 28.70% | 29.50% | 10.90% |

| Students have the opportunity and tools to reflect on and log the activities and experiences that helped them acquire soft skills | 38.80% | 18.10% | 26.30% | 16.80% |

| Students have the opportunity to evidence their acquisition of soft skills | 40.30% | 19.20% | 20.80% | 19.70% |

For every aspect courses and programme teams were felt by the majority to have primary responsibility, with academic departments and faculties also a popular choice. This finding reflects the close role that programme teams have to their students meaning they are perhaps best attuned to individual and group needs.

This is not to exclude the role of professional and student services in student development – indeed a good few respondents felt that professional services have primary responsibility across each of the areas of development we proposed. It was clear that many respondents felt that a successful strategy involved a collaborative partnership between academic departments and professional services.

Nevertheless, the findings suggest a recognition that soft skills are developed to a considerable extent – though not exclusively – through integration into the academic domain. A number of respondents pointed out the necessity of embedding skills development in academic curricula in order to ensure that all students – some of whom would not have access to, or interest in, the extracurricular offer – would be able to develop skills as part of their higher education experience.

Embedding skills in the curriculum

We asked respondents who have direct responsibility for teaching in a particular subject area to indicate what informs their approach to embedding skills in the curriculum. The three most popular answers (around 70 per cent in each case) were:

- The state of knowledge in the field

- Employer expectations in general (with specific industry requirements in the field a close fourth)

- Personal values and teaching philosophy

Less influential factors were institutional curriculum frameworks or policies, quality assurance, or external metrics. This suggests that efforts to develop curricula to incorporate essential skills will come less from the imposition of metrics or frameworks, and more from how thinking in the disciplinary field intersects with the possible futures they imagine for their students.

One barrier suggested in the qualitative feedback was about academic bandwidth and the openness of institutions to allow for complexity and development:

In general, most academics would like the opportunity to teach better, to think through these issues, but institutions don’t seem to offer ‘teaching leave’, i.e. the time to do the thinking and the preparation, and aren’t all that keen on acknowledging difficult questions.

Another comment reported a gap between the skills academics perceived students to need and those the students themselves valued:

Our student feedback demonstrates a slippage between what the university and course teams understand to be important skills and what students understand as skills (in a traditionally vocational creative discipline). For this reason, questions about skills contribute to student satisfaction issues. It’s my gut feeling that maturity is a factor in understanding what skills will be meaningful in the long term and this makes it tricky to square with student satisfaction. I would like to figure out how to build more trust with students around these questions.

Another sought to establish a hierarchy of subject knowledge and soft skills in curriculum development:

The development and ‘acquisition’ of soft skills should not drive curriculum content or pedagogical approaches, but should definitely be a consideration when these elements are developed or redeveloped. Students do not/should not come to university to learn all of these skills specifically, but to graduate students without them is unconscionable.

And another astutely suggested that academic staff having, and valuing, the relevant skills would be the most likely basis on which students could acquire them:

My research is on internationalisation of the curriculum and it has similar status and limitations! I think developing the staff skills comes first. When they have these skills, and value them, they are more likely to teach them.

In the qualitative responses there was a strand of thinking – not overwhelming, but definitely present – that tended to consider academics in general as uninterested in students’ development of skills.

For example, one respondent said: “In my experience as an employee in a HE careers and employability service, it continues to be an ongoing battle to engage most academic colleagues in supporting students in the development of the skills and attributes required for a world outside of academia.” Another said, “departments are not encouraged to promote learning in this area as it isn’t seen as core academia.”

Monitoring students’ acquisition of skills

We wondered if, and how, student acquisition of skills is being monitored and evaluated. Because respondents to our survey were not replying on behalf of their institution, the responses do not map onto the proportion of institutions adopting the different approaches, but may give some indication of the relative popularity of each.

The most popular method, adopted in institutions of just under half (46 per cent) of respondents, was via a personal development plan or student portfolio. Around two fifths reported their institution uses course revision and approval processes to evaluate this, with just under a third making use of specific enhancement initiatives. A quarter said their institution uses teaching evaluations, and the same proportion selected student feedback analysis. More than a fifth were unsure and the qualitative commentary picked up instances where the approach was reported as being inconsistent or absent.

There was also some scepticism that questioned if it is possible to objectively and reliably monitor and measure skills acquisition:

I believe that there is a great deal of subjectivity when interpreting someone’s soft skills, which means that there is a potential for bias. As such, I am not sure how this should be effectively assessed.

Another respondent said:

The whole point is they often can’t be measured or assessed. How would you assess resilience for instance? And creativity can take so many different forms. Students might not realise they’ve got these skills till they need them, so I think we just have to give them as much opportunity as we can of developing and using them.

In a context where external monitoring may not offer the most productive stimulus for development of practice, it would be hasty to identify a lack of, or inconsistency in, monitoring as an area for development.

Yet if student skills development is a strategic objective of the institution, and recognised as part of the value proposition offered to students, it would be a concern if the institution did not have the data gathering mechanisms to be able to judge the extent to which the strategy was being achieved – particularly in the context of equality, diversity, and inclusion:

I work at a post-1992 university where many students lack confidence and the ability to sell themselves or their degree, often lacking the ‘social capital’ associated with ‘elite’ universities (a term used far too widely by government and the press). Reflection on soft skills development and personal development throughout their studies is the best way for students to bridge this gap, applying their studies to a personal narrative of experience, skills and confidence.

When asked to rate how effectively their institution supports students to develop soft skills on a scale of one to five (with five signifying “very effective) just under half (49 per cent) selected either four or five.

There was some difference in scoring between academics from different subject areas, shown in the table below.

How effectively do you think your institution supports students to develop soft skills?

| 1 or 2 | 3 | 4 or 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All respondents | 15.60% | 36% | 48.50% |

| Sciences | 10.10% | 30.20% | 59.70% |

| Arts, humanities and social sciences | 14% | 36.40% | 49.70% |

| Academic-adjacent professionals | 15.10% | 36.60% | 45.40% |

Conclusions and reflections

While we would not recommend drawing any fixed conclusions from a single snapshot survey, we hope it provides some extra insight to inform institutional and sector wide discussions in this area.

Bridging the language gap

Within universities students development is perceived as much more complex than the acquisition of a defined set of skills – but the language, and professional practices that reflect that complexity are contested, as are the intended outcomes and objectives.

The qualitative feedback from this survey, which is supported by our conversations with university leaders, highlights a key challenge of persuading students to recognise, take ownership of, and engage in their own development trajectory. In most cases this will only happen when students perceive it to be relevant and meaningful to their present and/or their possible future. The presentation of abstract skills as things to be “acquired” may not meet this criteria.

As such we think it is important to find a language that is meaningful to, and resonates with, students and their sense of where they are trying to get to, their professional context and relevance. This needn’t mean shutting down healthy academic debate, or flattening complex ideas in the name of accessibility – but it does mean connecting with and understanding students’ aspirations and world views.

The role of collaboration and partnership in producing the curriculum

While universities certainly adopt a range of approaches to developing students’ “soft” skills, the academic curriculum is clearly central in that process. Concrete strategies for infusing skills development into the curriculum are therefore essential.

The corollary is that academics must either take on responsibility for students’ skills development or – more productively – work in partnership with other actors to develop and enhance this aspect of the curriculum. Based on the qualitative feedback to the survey, where these partnerships are happening, they are experienced positively, but there are also barriers for some to achieving partnership nirvana.

There’s some indication that staff are struggling to find space and time for thinking and developing practice in student development, which improved collaboration could help to mitigate to some extent.

Our survey suggests that approaching the issue from the basis of shared values is likely to be more effective than adopting a more traditional technocratic approach – which is likely to lead to the dreaded “tick box”.

Tracking, monitoring and evaluation of student development

It’s clear from the response that there is a patchwork approach to monitoring and evaluation of students’ acquisition of soft skills. This need not be an issue in itself – some subjects may lend themselves more readily to building skills evaluation into formal assessment; institutions and programme teams may have different views on the ethics of directing students in a particular direction for their development, and so on.

But responses also indicate that it’s not clear in every case what is being tracked and why. Tracking to identify skills gaps is different from tracking to enable students to articulate and evidence their skills. Formal assessment of skills as part of the academic programme may be appropriate, or it may not be. And the range and scope of opportunities for skills development may also be a subject of monitoring, in order to enhance the overall offer, and ensure it is equitable and accessible.

The most important thing is probably to decide which of “tracking”, “assessment” and “evaluation” are important, what purpose each serves in providing actionable information to staff and students, and how they inform or reinforce each other.

You can download the slide deck presenting the main findings of the Skills to Thrive survey here.

This article is published in association with Adobe. Join Wonkhe and Adobe on 12 January for Skills to Thrive – equipping graduates to take on the world.

This is an incredibly important piece of work. As someone who has worked in the sector for 30 years to find ways of integrating skills development into academic curricula and is now working outside the sector in executive search I am deeply concerned that leadership, empathy, inclusion, networking and inter-cultural competence appear to be scoring so low in the survey. These are all the attributes we are looking for in our leaders of the future as we seek a more inclusive culture that embraces diversity. It would be interesting to run this same survey with employers to compare the results.

I think this concern relates more to semantics than whether these competences are valued. I think they are all covered in different categories with a variety of names. Personally, I like the umbrella heading ‘Personal Agency’ and the elements listed beneath it. I think ‘leadership’ in particular, is a hackneyed word that is actually a range of skills, all of which are covered in the list. I also think ‘Inclusion’ is a way of operating and a value, not a competence

Whenever there are discussions about skills development I am struck by the huge potential SUs have to play a larger role in this. Students who are highly engaged with their SUs have a great deal more exposure to opportunities to develop these skills by working on self directed projects. I know this model doesn’t work for some students, particularly those with other responsibilities or those studying part time, but I feel there could be some really exciting work done here in some Universities to pilot a partnership approach between the SU and University to formalize and recognise some of that… Read more »

I agree this is a very helpful piece of work. I’d note though that employers are a major stakeholder in this area and there is relatively little in the report on their influence and the partnership role they must play to achieve a successful skills development programme. Perhaps the Skills to Thrive event will address this?

I guess what we must recall here is that we are looking at academic perceptions. As an entrepreneur and academic I see other views, and applaud what QAA and AdvanceHE are trying to achieve in areas such as enterprise and sustainability.

Working as a technical staff in HE. My observation from the students I assist is that, they are not always aware of how transferable some of the skills they posses are to other domains. Either they are not made aware of this or they tend to be fixed on a particular industry and how they apply the supposed skill in question. Curriculum design should explore ways to expose students to alternative industries that skills gained in one particular discipline are valued. Also there needs to be more emphasis on entrepreneurship as it encapsulates a lot of the skills that employers… Read more »

As a Careers Adviser in HE its easy to fault academics or look at it from a careers, student or employer centric point of view. However, the skills agenda is part of a wider employability agenda which is part of an even bigger Graduate Outcomes (and DLHE before that). Faults or ‘ideal’ solutions are easy to find in theory because they are not at the top of the other stakeholders agenda…time and resource poverty appear to be big issues that I have encountered professionally and the findings of the article too. The article intimates the shifting confines that we work… Read more »