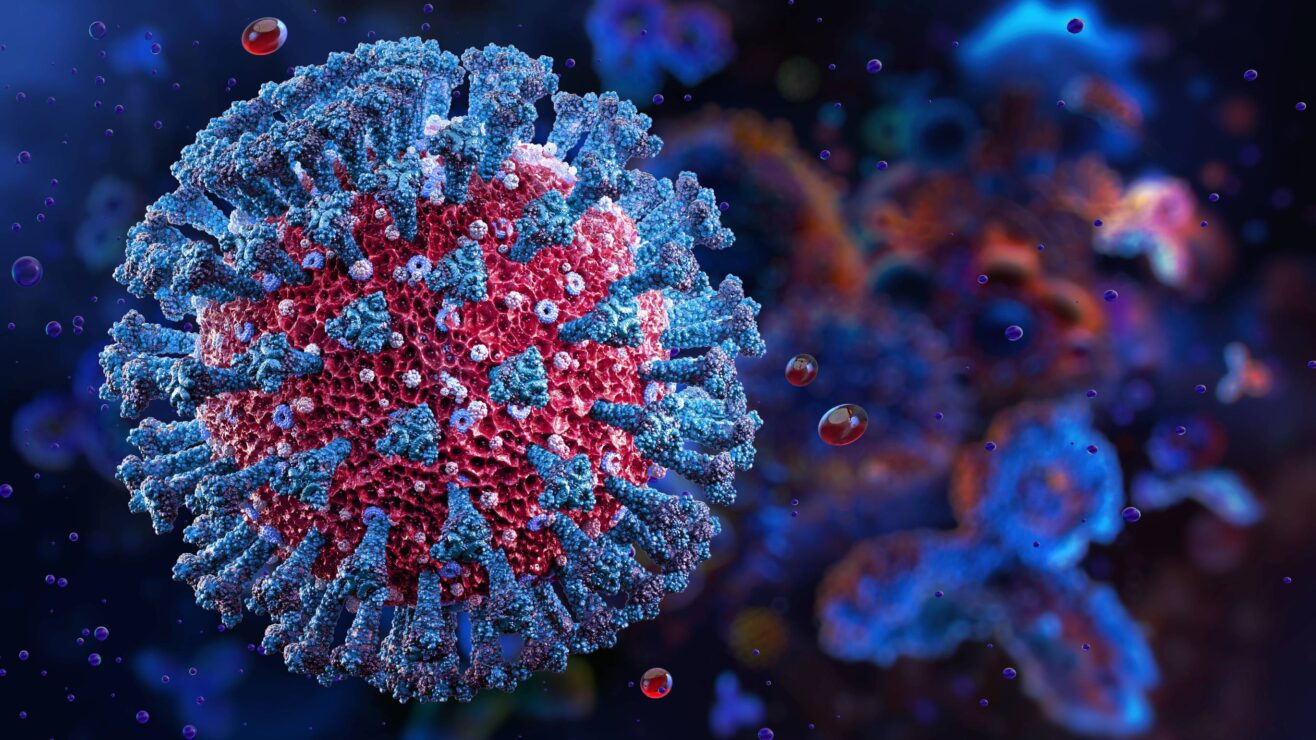

The vast majority of cells in the body aren’t yours – they are bacteria. Most of them are pretty fantastic – good at helping you do the things that you need to do to remain alive. And, to them, you are equally good news. You’re a life support system for your own personal ecology.

A big proportion of your bacteria hang out in your lower intestine – that’s where most of the important things happen, and where a lot of important decisions are made. If your body is a country full of bacteria, your lower intestine is a slightly better-smelling London.

The suggestion that maybe the bacteria are in charge of the people is a common enough trope among mischievous gut microbiologists, but in a sober light most would agree that we get a lot of benefit from having so many of them around. Having a gut full of alien DNA (we call it the “microbiome”) might have its downsides too, as not everything is as friendly as the stuff in the Yakult advert and we’re only just beginning to learn more about this fascinating area of human biology.

From genes to memes

When Dawkins originally came up with the idea of the “meme” it had little to do with pictures on the internet. Ideas – he hypothesised – need to reproduce in the same way as genetic material does. You carry a lot of ideas, and not all of them are yours. The most successful ones – and the most beneficial ones – become more prevalent in your society. Those that harm you die out. That’s the idea anyway.

So let’s tell the story of one little idea – the DNA in one little intellectual bacterium – that has done a lot for civilisation.

Around about 387 BC a bunch of ancient Greeks decided to get together and chat about stuff. The world was (and remains) an amazing place – they wanted to know where it came from and how it works? These two questions have never been satisfactorily answered, but as far as we know these ancient philosophers were some the first people we know of to ask them in this particular way.

There have always been explanations, but these were based on belief. Or more accurately, on a suspension of disbelief. We might choose to believe the world is a flat disc supported by turtles, but if we’ve never seen the edges of the disc or the turtles this is never entirely satisfying. The way they decided to answer the question was by using their senses and faculties – their eyes, ears, and reason – to make and test predictions. And they chose to build on what other people had perceived before them.

A bacterium is born

Very broadly, this was the birth of a particularly virulent strain of memetic bacteria. Let’s call it academia. It spread to all corners of the known world. And it was good news.

People with the infection found they made better decisions. They were good at arguing their point, great at solving problems. They were open to new ideas – and found it easier to evaluate them. They knew how to build stuff that worked. But the big benefit was to their wider society – get a handful of carriers together and they could do incredible things. They could heal the sick, calm the angry, and measure the distance between the stars. They built libraries, civil structures, and great machines. And they infected the people they worked with.

At different moments in history, this infection has been seen as beneficial or troublesome. Sometimes societies built special environments to encourage carriers to cluster together and infect their young people. Other times, they tied carriers to bits of wood and burnt them.

In the early modern era giant petri-dishes were being built to foster these infections. We called them universities. They were expensive to build and maintain, and often caused a lot of trouble. Academia was awfully good at undermining other, less successful organisms. Organisms that may have once held a lot of power.

Enter the network

Here’s where it gets weird. Academia isn’t just a load of independent memetic bacteria. You could also see it as a single network of organisms – connected around the world. This network has a bunch of homeostatic systems – peer review, collaboration, academic publications (though frankly academic publishers might turn out to be an opportunistic parasite – and you have those in your gut too!)

Even a mild infection can cause sympathy in the carrier with a range of sometimes undesirable political views (often manifesting as globalism, alongside an acute case of social justice). You need both of these to participate in the wider academic network – but when you do other things (like run for political power or write a column in a popular tabloid) they can cause problems

In recent years the expense of building and maintaining the university petri-dishes has been made more explicit via a decision to place the cost nominally on those who wish to become infected. This happened just as political fashions have begun to dictate that more effects of the infection are undesirable, and carefully chosen data has begun to show that even the desirable effects seem to be lessening. It would be remiss of me to fail to note that the our current crop of petri-dishes are awaiting the Augar review.

Competition and symbiosis

There are other organisms out there competing for the same space – religion is a good historic example. A more modern one is populism – if what you think is what you feel then we’re back out of the other end of the academic empiricism that kicked this off.

All of which leaves us with a very large problem – the civilisational host seems to be rejecting (for whatever reason) our very special bacteria. And they are rejecting the aspects that bring the greatest, yet least tangible, benefits – the same aspects that make our wider network function.

It’s far from fashionable to make this claim – but perhaps what academia is doing isn’t the problem? Sure, it could get a lot better at explaining how it works and why, but my feeling is that it is being pushed out of it’s niche by a malfunctioning civilisational immune system. And an insurgent infection – that of populism – has discovered that academia is antithetical to it taking back control.

Probiotics are one way of encouraging a healthy biome, but designing them is tricky. Many potentially useful substances will never get as far as the parts of the gut that need them – and are instead broken down by other parts of the digestive or immune system.

But if we feel like we are struggling with a harmful societal infection perhaps addressing that is the primary concern. Bacteria can use various means of triggering the immune system to root out competitors in the same space – so the question we need to be asking is not “how can we preserve academia?”, it is about how can academia preserve civilisation. How can we restore the symbiotic relationship that has been of such benefit to the world of ideas and the world of action?