Right across Europe, growth has been slowing – down to zero in real terms.

And that means that just as in the UK, massified higher education systems have been enjoying strong demand for participation, but little support from taxpayers to pay for that participation.

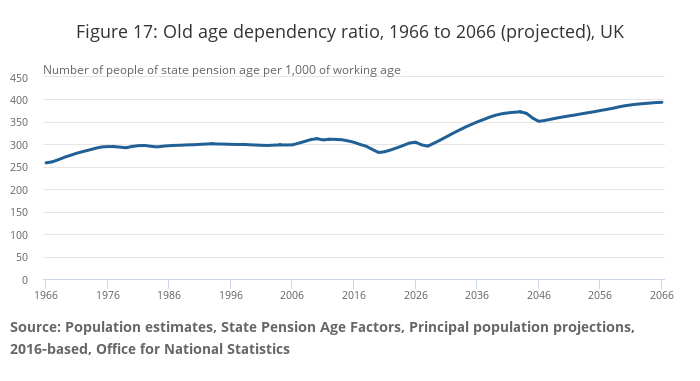

As birth rates decline, and populations age, the need to increase spend on health and the need to generate economic output from the young is increasing.

Controversies over significant cuts to higher education in France and the Netherlands are the latest in a line of countries tightening their spend on tertiary education, as governments demand more efficiency from the systems they have.

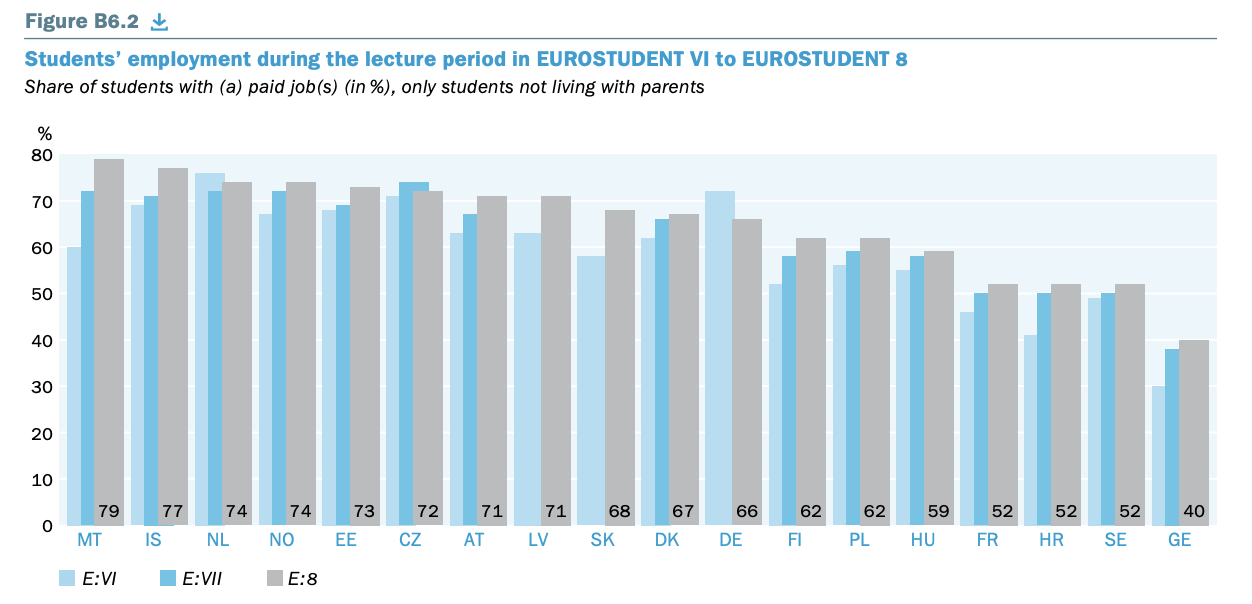

But those efficiency demands are not restricted to universities. Increasingly, efficiency is being demanded of students themselves. Eurostudent shows the volume of “full-time” students working during term-time is on the increase almost everywhere, as direct maintenance support comes under similar pressures.

The working – and arguably lazy – assumption has always been that this would mean students would be “priced out” of education. That may well yet happen. But students and their families tend to be ambitious – and so it has been earning while learning, rather than abandoning it altogether, which has seemed to be on the increase.

That seems to be true of international students too – the countries that the UK recruits from today are not nearly as prosperous as those that dominated the figures a decade ago. Currency changes have made Central, Northern and Western Europe more expensive places to study, and it looks like that is impacting students’ country of choice, and how they participate while studying.

There is already quite a bit of evidence on the numbers of students working, the hours that students are working, and how that differs by socioeconomic status, nationality, or programme type.

Last year’s HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey (SAES), for example, told us that more than half of full-time (undergraduate) students are now working, spending on average nearly two days a week doing so, and when combined with time spent on study, students with jobs are averaging 48-hours working and studying – far more than the 36.6 hours that the Office for National Statistics says adults are working for in the population in general.

So given the volume of students at work and the volume of hours they are putting in, we wanted to understand more deeply what their experience was of work. Our subscriber students’ unions were keen to know what sorts of jobs students are doing, how long it takes to get to work, how they are treated and whether their work is rewarding, helpful or educational.

To this end the latest tranche of Belong, our polling partnership with Cibyl (which our subscriber SUs can take part in for free), we’ve been interrogating students at work from multiple angles. Polling that follows is from a wave in November, weighted for gender and qualification type. The total number of students who participated in this wave of Belong is 2,853, of which 1,461 reported being in work.

Click here to view and download the full deck of findings

Motivations

We are not presenting here what we might regard as nationally reliable percentages of students undertaking employment while studying. That’s partly because as the weeks of the wave went on, the percentages changed – many students will have realised they need to find work, and many will have taken some time to find that work.

More reliable figures might arguably be found in other large-scale survey work and in future waves. What we have done is focus on the experience and impacts of finding and undertaking work while studying.

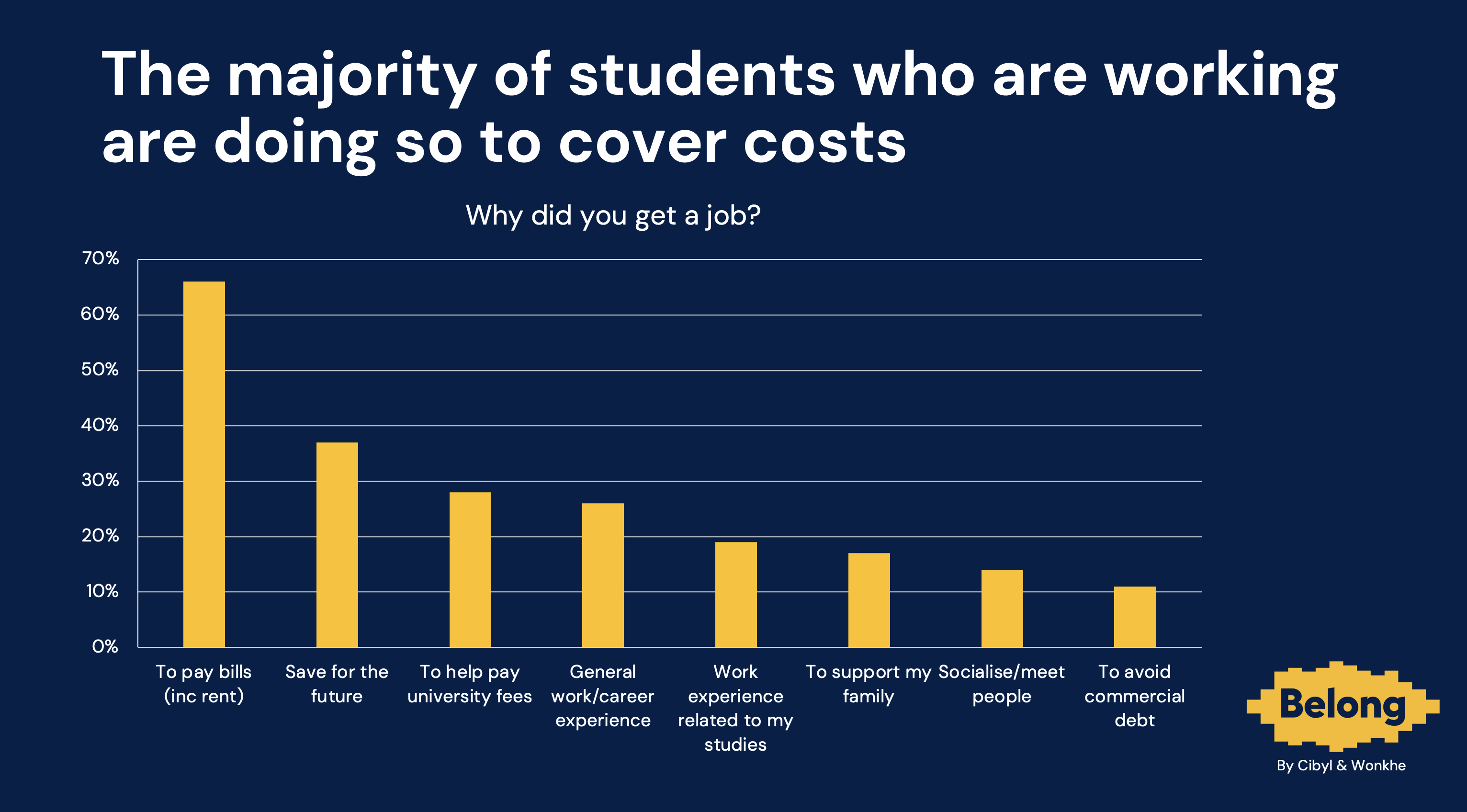

We first wanted to understand why students had sought employment. Students could choose more than one option – and the high percentage (almost one in four) doing so to “save for the future” may reflect either naivety or a future more immediate than the phrase tends to imply.

Either way, there are some surprising findings. 17 per cent of students work to financially support their family – up at one in five international students – yet our mental model (and our home domiciled funding system) tends to assume that it is families supporting students.

More than a quarter of students are working to help pay their fees, concentrated across PGTs, for both home and international. That two thirds of students report they work to pay for essential bills reminds us that we are some distance from the cliche of students working to earn extra for leisure – the vast majority are working to live.

Travel

We know from previous waves and the SAES that there have been increases over time in the hours students work, and differences between (for example) social class. The widely recommended volume of hours over which every major study suggests that health and outcomes suffer is 15 hours – in previous waves of our survey work we have found that for home domiciled students, 27 per cent of those from the more advantaged social class groups ABC1 with a job were working over that limit, while 71 per cent of those from less advantaged/working class C2DE backgrounds were doing so.

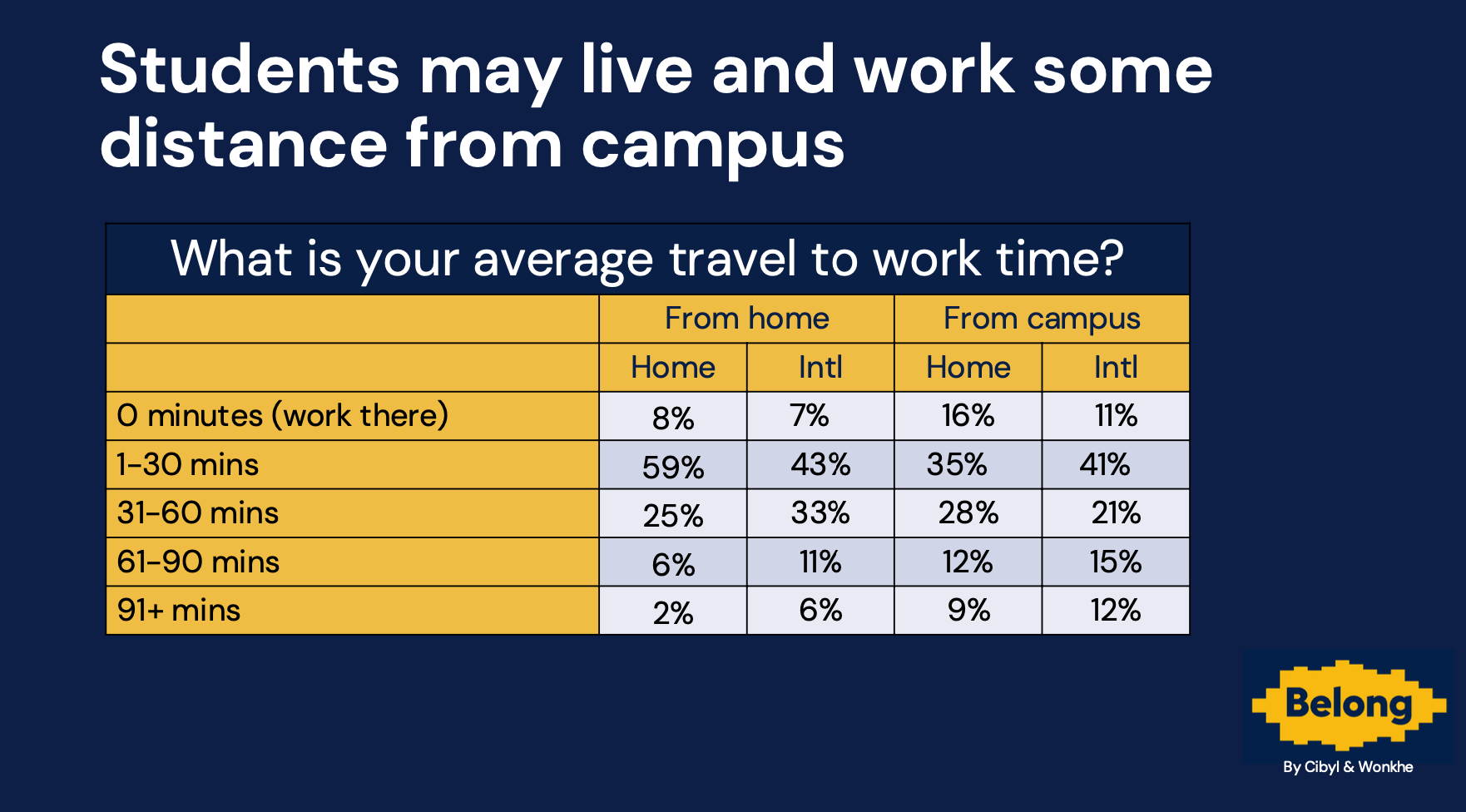

But hours spent at work and on independent study don’t account for the time spent travelling to work. In our sample, almost one in five home students have a 60+ minutes travel to work time from campus, rising to 27 per cent of international students.

Home to work travel time is shorter – but it is no wonder universities and SUs are reporting that they are struggling to get students to come to campus. Their homes and their workplaces are increasingly distant, and when these travel times are added onto each shift each week, the amount of time left for personal care, social activity or even study is significantly reduced.

Type of work

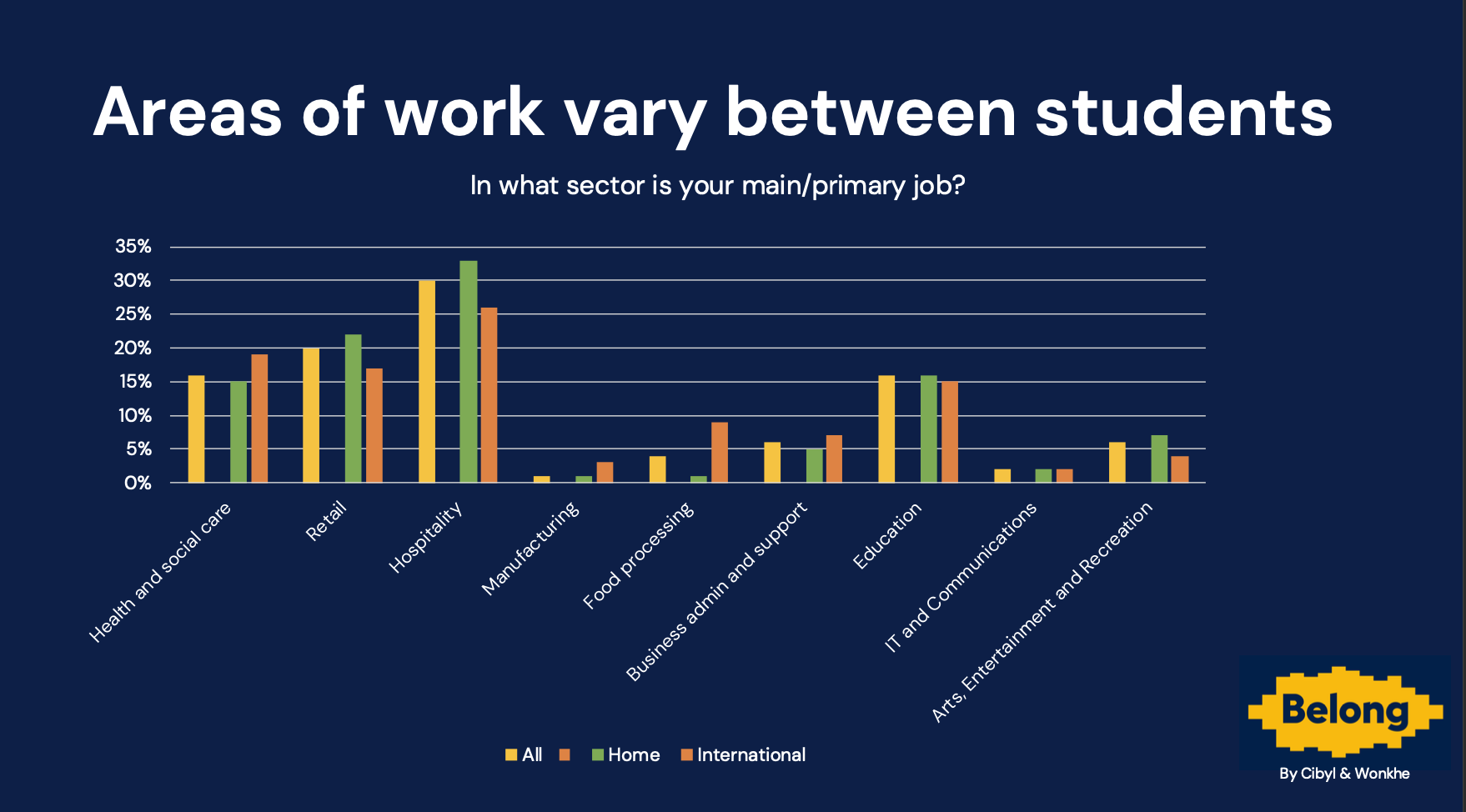

The cliche of student work might conjure images of a student in a coffee shop or a bar, morphing slowly into other cliches, like the student in a post-92 institution working a nightclub shift to serve the hedonism of their pre-92 peers in a given city. What is less understood is the volume of students not working in those kinds of environments at all.

Retail and hospitality dominate as we might expect. But in our sample, almost one in five international students are working in health and social care, and almost one in ten are working in food processing. It is possible, of course, for work in all of the major industrial categories to be well paid, educational and rewarding – but it has to be the case that some sorts of student work are better aligned to the goals and demands of full-time study than others.

Increasingly, it is clear that students – both home and international – are supplying large volumes of labour in industries which do not only serve other students, but rather care for and feed the population as a whole. And more broadly, while we used to think of full-time students joining the labour market upon graduation, it is increasingly clear that students are already in it, and make up a significant proportion of it in some industries.

Looking for work

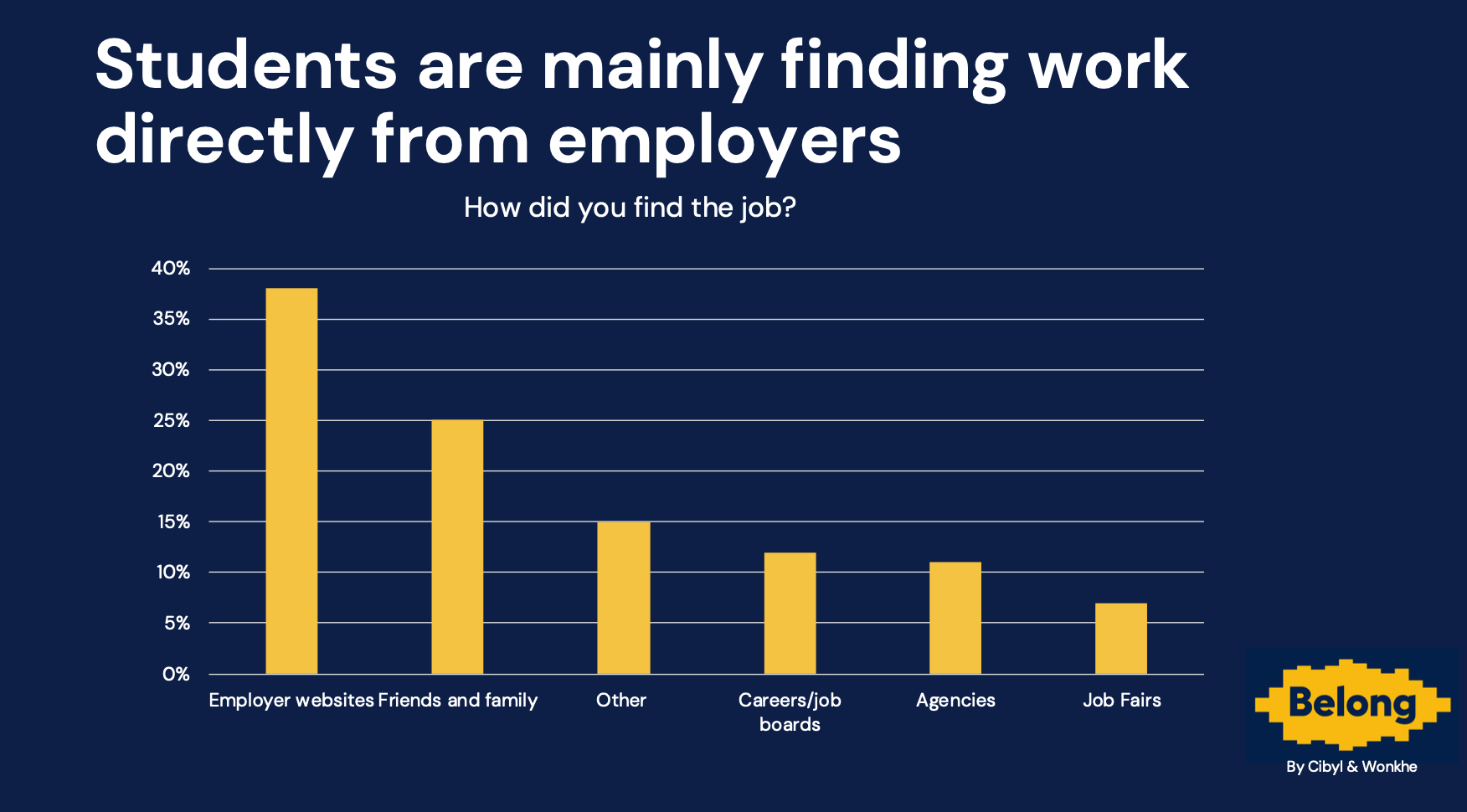

We were quite interested to discover how students found work. A minority of students have found the job they are doing via a university or SU service, with the majority relying on web searches or friends and family, a resource which is not evenly distributed between the diversity of students on campus.

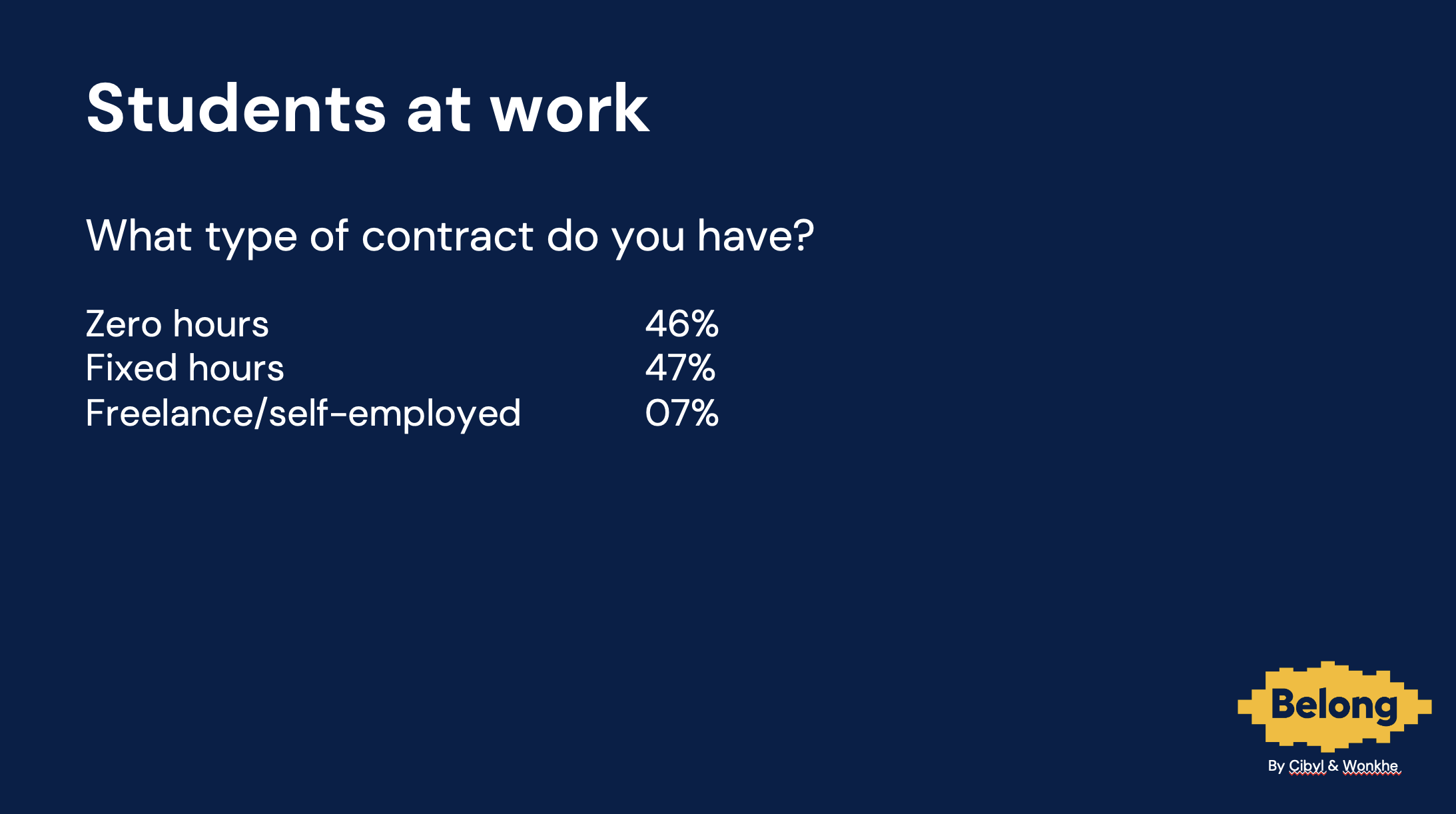

We were also keen to understand the type of contract that students held – not least because there are real risks in the forthcoming Employment Rights Bill, given its reduction of flexibility in “zero hours” contracts could see a significant reduction in the availability of such jobs both on-campus and in the community.

In our sample, almost half of students are on a zero-hours contract, a figure which should worry both universities and ministers, given the centrality of the role that student work plays in helping to fund students’ participation. Measures which unnecessarily restrict the volume of student jobs should be avoided, while frameworks that enable them should be a policy priority, as we see across Europe.

Costs crunch

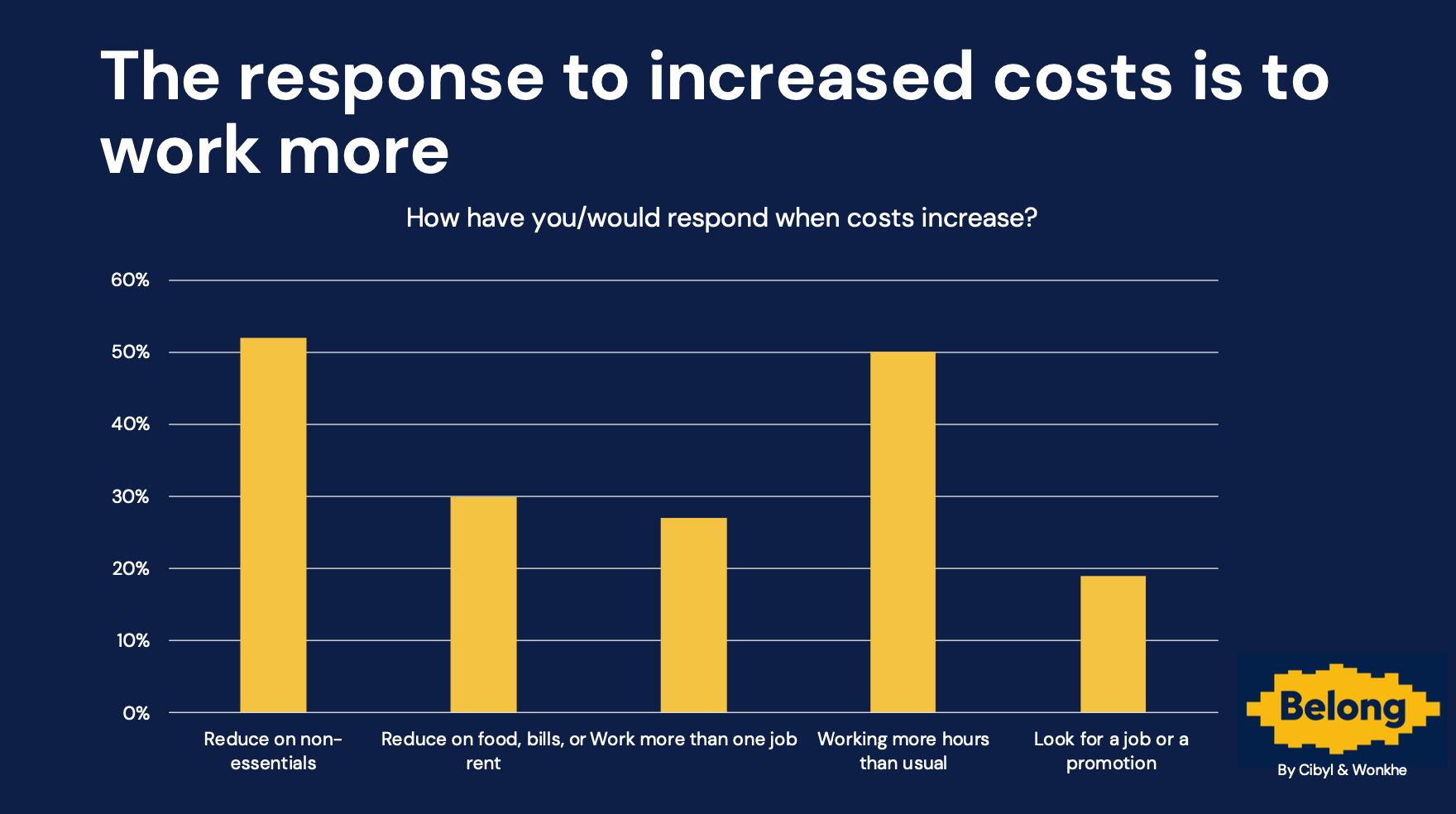

From a participation perspective, we wanted to understand both how students respond (or intend to respond) when their costs increase, and the impacts on them when responding.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, while some students do seek to reduce their expenditure when they hit a financial problem, the most popular response on the income side was to seek to work longer hours, with a large proportion of students seeking to find a second job. Both will have impacts on health and study.

That helps to illustrate some of the on-campus attendance issues that many are discussing anecdotally – and reflects how difficult the “sunk costs” of higher education make it to drop out. It also reflects earlier qualitative findings in our work on belonging, which found students prioritising activities that enabled them to feel in control over applying for (often uncertain and delayed) hardship funding.

We have discussed before the way in which both the student finance system and the visa regime make it almost impossible for a student to formally reduce their study intensity – we have, for example, the youngest Bachelors graduates in the OECD – but what is clear is that while the theoretical study duration is comparatively rapid, the quality of the participation is taking a real hit for some students.

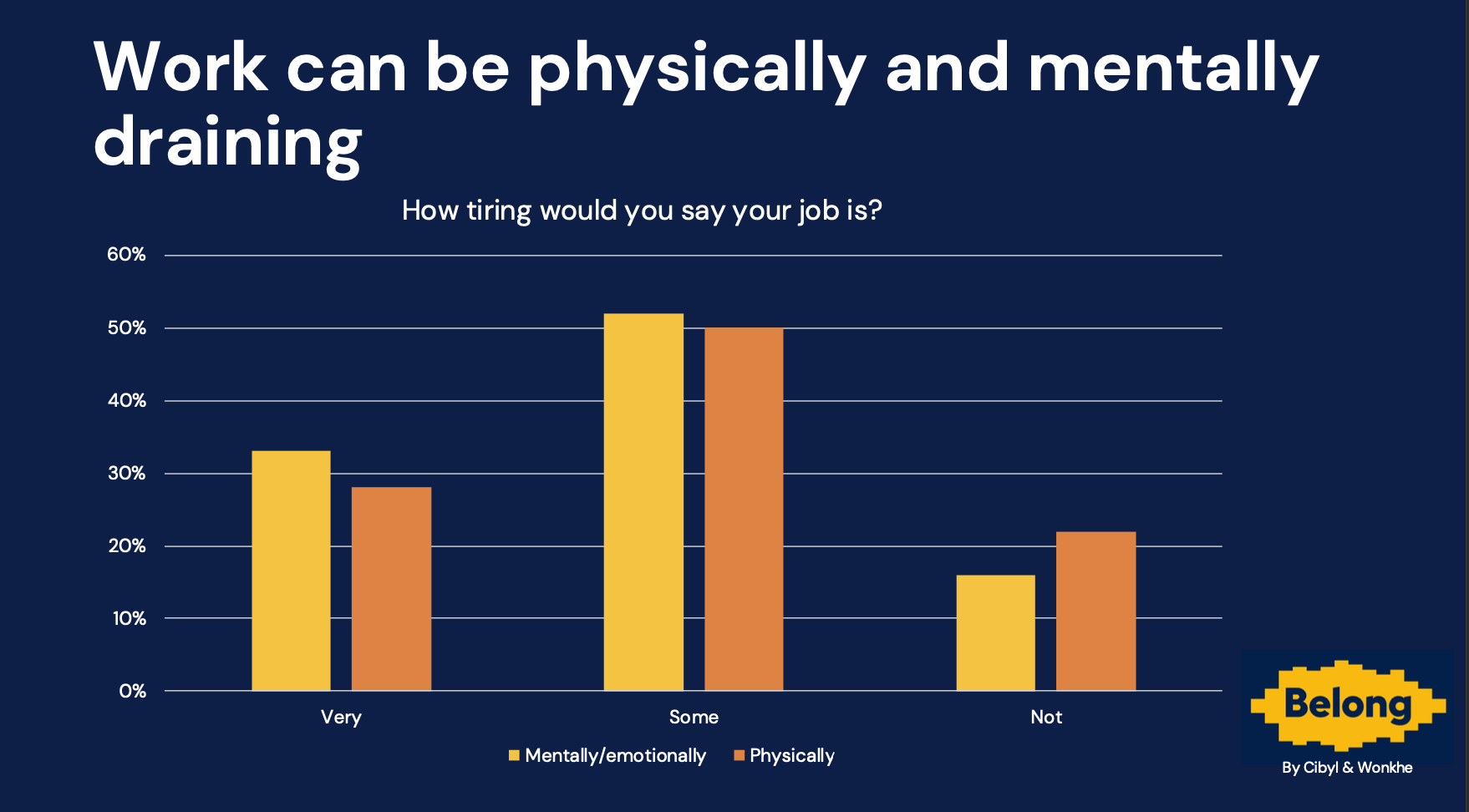

As well as the established impacts on outcomes, this volume of work takes its toll on students personally. In our sample three in ten students say their work is “very” physically tiring, while more than three in ten say the same in terms of emotional/mental impact.

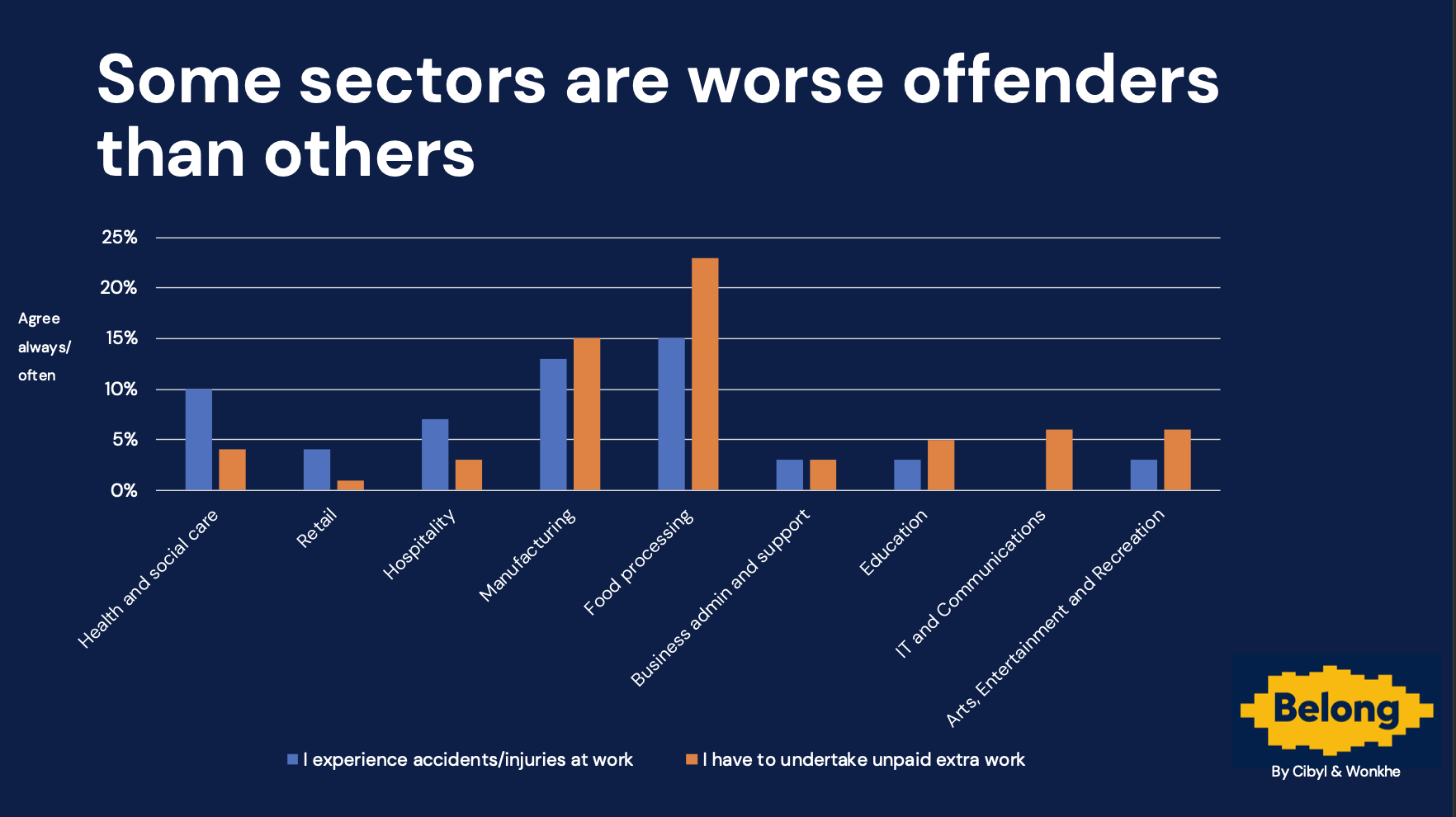

Those impacts differ by industry. Across health and social care, retail, hospitality, manufacturing and food processing, work is “very” physically tiring for over a third of students – falling to below 10 per cent for other roles. There are similar differentials on the mental side – with health and

social care taking a particular toll from both perspectives. And the more mentally tiring students said their work was, the worse their mental scores.

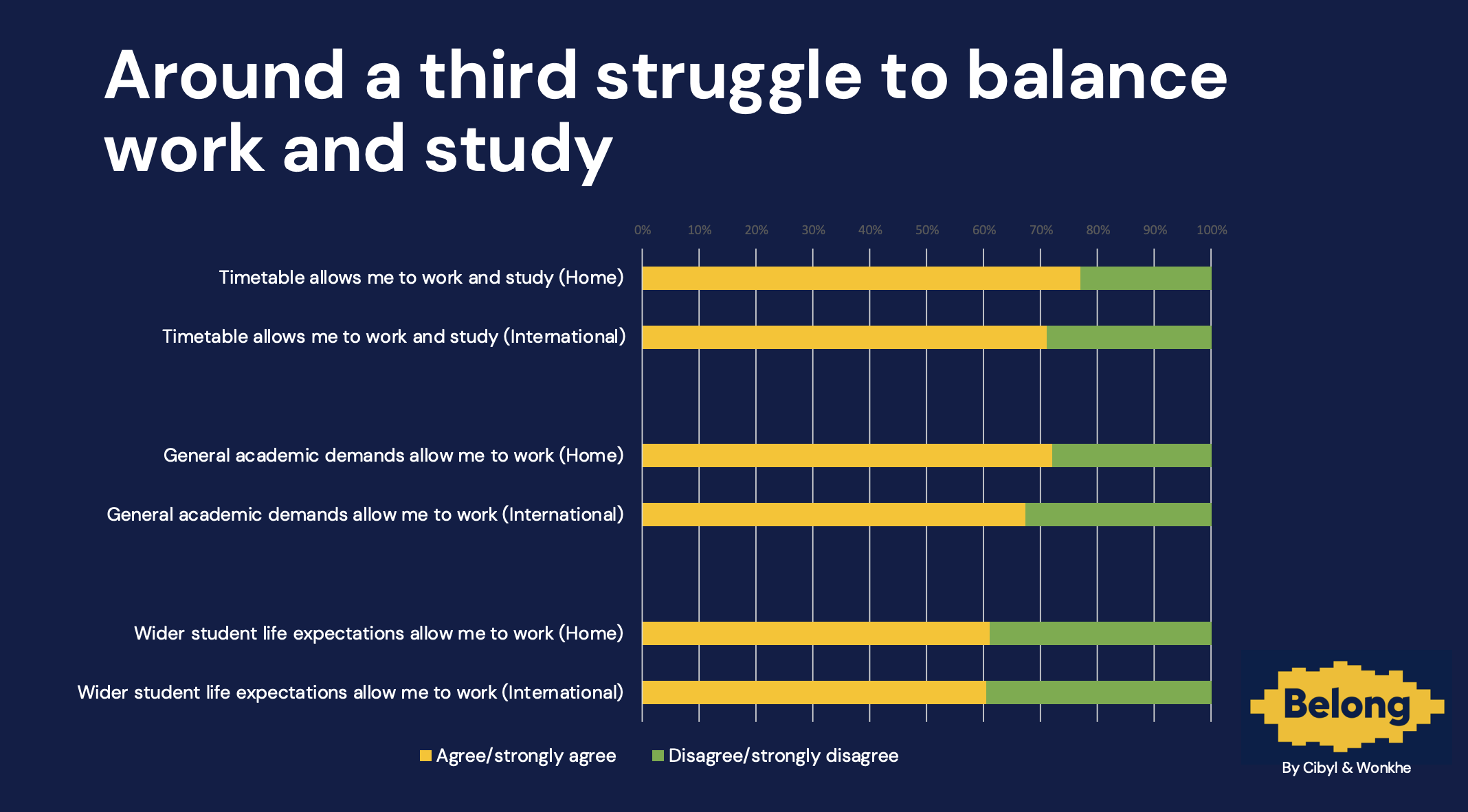

But it is the interrelationship with their studies that is most stark. We asked students about the extent to which it all “hangs together” – by asking them to reflect on the extent to which their timetable, the academic demands of the course and their wider expectations with student life are compatible with being at work. The levels of disagreement should worry policymakers at all levels.

Treatment

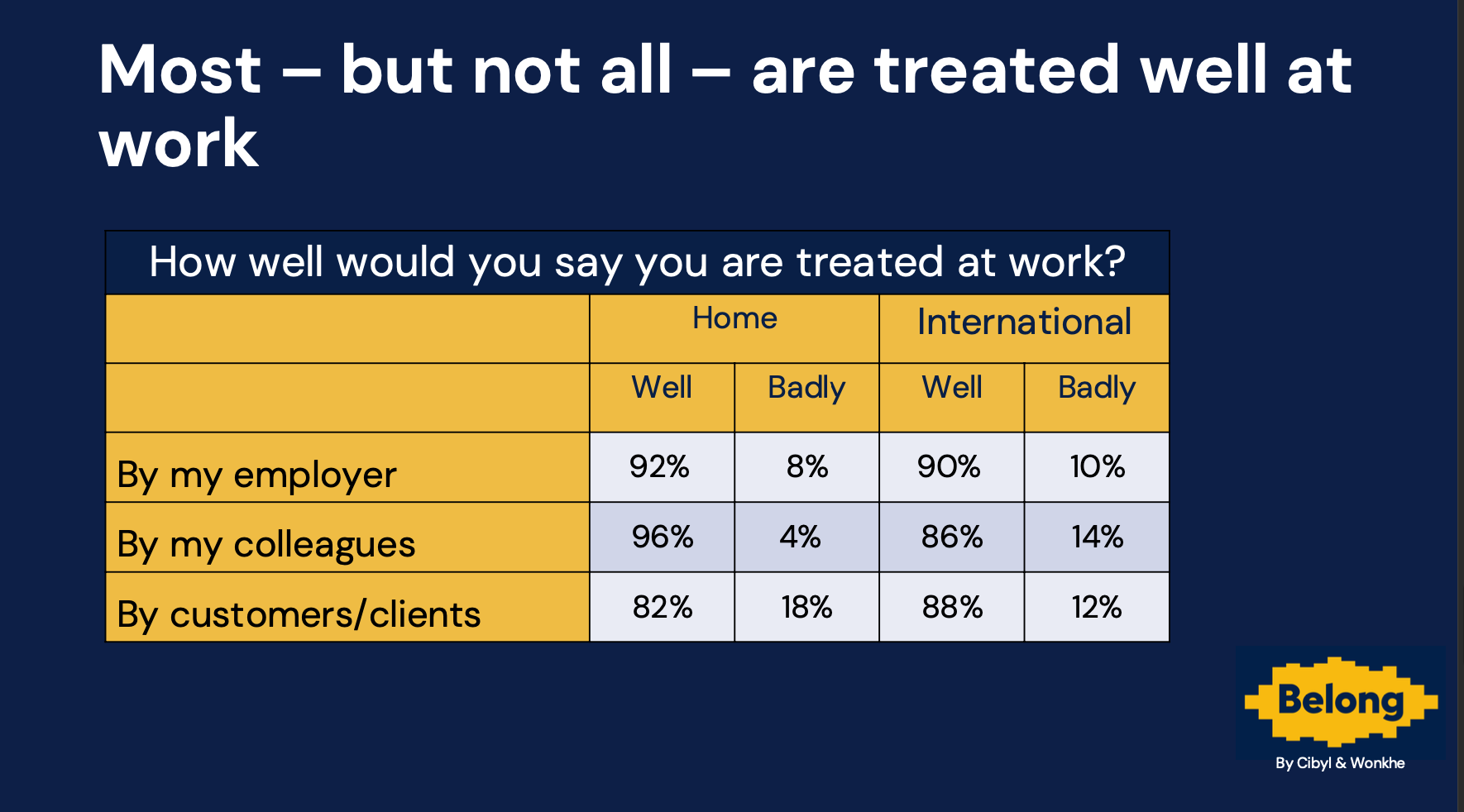

We were interested in the treatment of students at work, both to help illustrate problems that need to be solved, and to help think through how that treatment might interact with their “student” student experience.

International students’ perceptions suggest that they are more likely to be treated quite badly – a finding we are keen to interrogate further. But more generally, a significant minority face poor treatment from customers or clients – and is usually much harder for those in less secure forms of work to complain about or tackle.

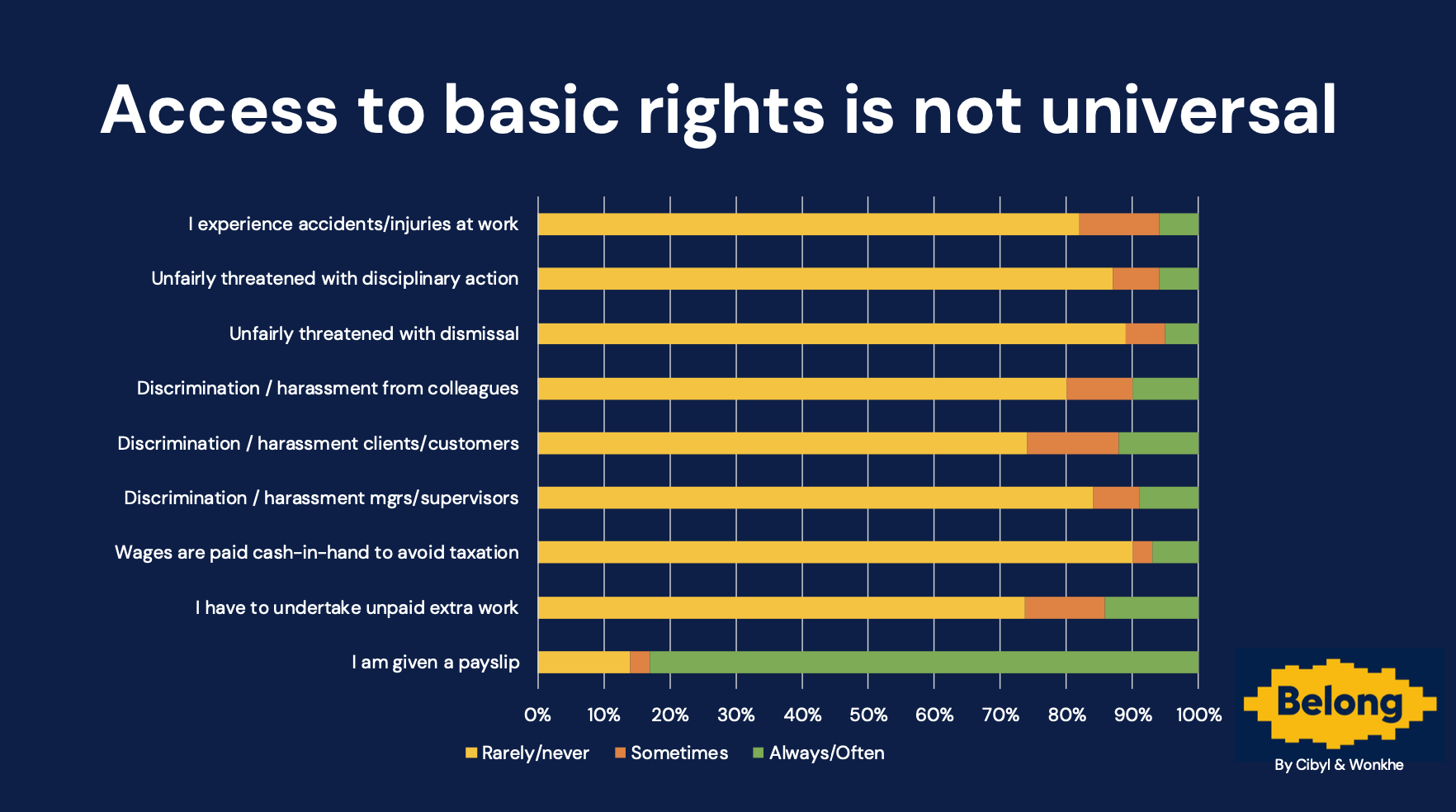

We then asked about basic rights at work. Only 83 per cent of students are “often or always” getting a payslip, one in four are regularly required to work unpaid extra hours, and one in four regularly experience accidents or injuries at work. Discrimination at work – from employers, colleagues and clients/customers is also a significant problem – and a significant minority are threatened with disciplinary action or dismissal.

The supply of work, the extent to which students rely on it to live, and the precarious nature of the contracts which surround it are conditions ripe for exploitation, and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this is exactly what is happening for significant numbers of students.

It also raises real questions about a system which is starting to offer real protections for the part of a students’ life that is concerned with the university, while similar protections for the working portion of their lives are unavailable.

Crucially, it must be the case that students who work a little are more employable, and the major studies suggest that a reasonable volume of work assists with outcomes, belonging and health.

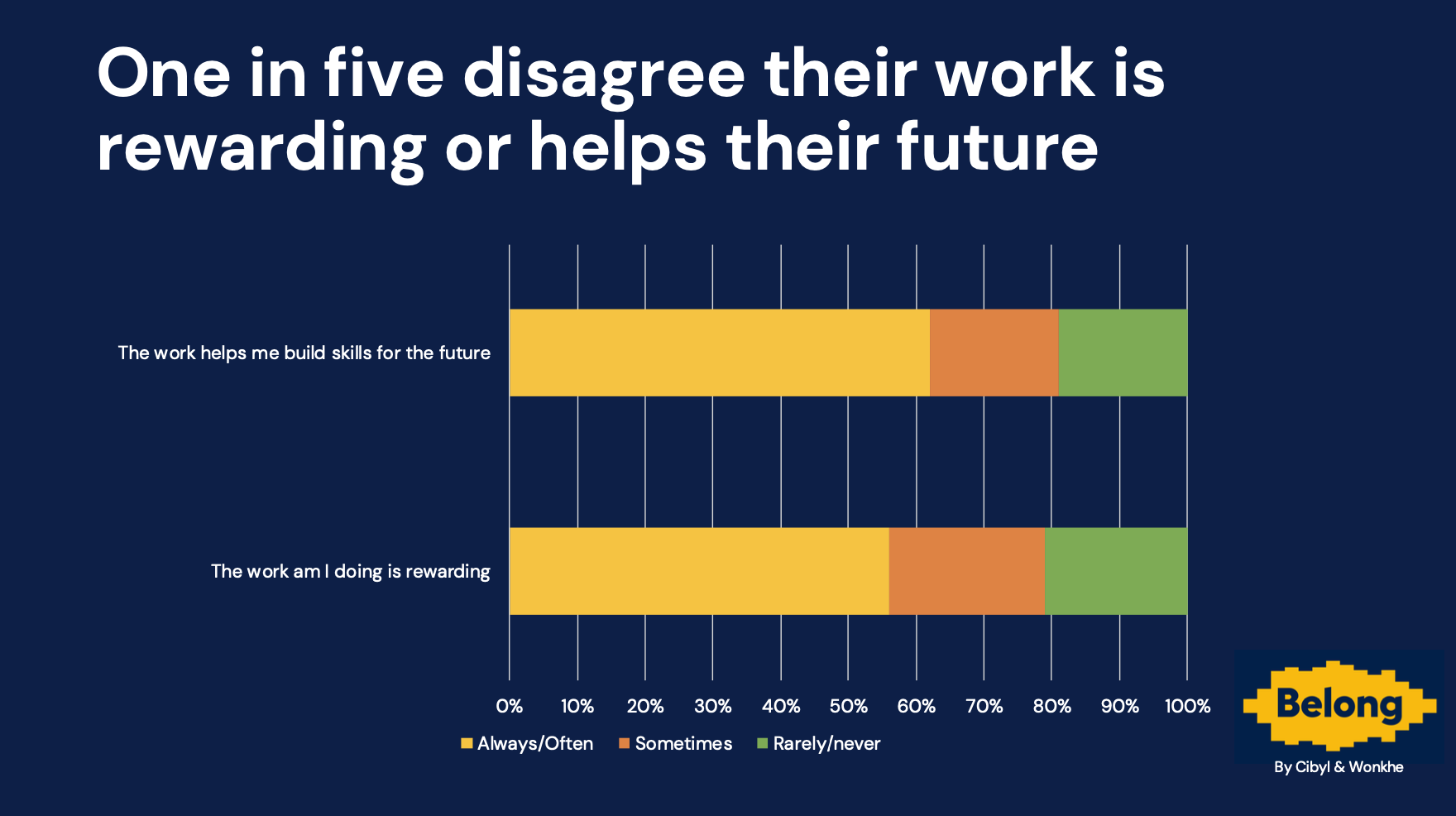

But in our sample only 56 per cent of students at work found their work rewarding, and only 62 per cent felt they were developing skills. The benefits of student work are neither universal nor evenly distributed – and again vary significantly by industry.

Voices on what would help

In the qualitative part of the polling, we wanted to hear from students on what they felt would help. A key agenda in the comments was flexibility – timetables released earlier to allow better planning, lectures not being cancelled or moved in ways that impacts students’ reputation for reliability with an employer, and more compact timetables to help accommodate work commitments were all front and centre. Even little things – like assignment deadlines in the evening to provide more manageable timelines for those juggling other obligations, put in a showing:

Get timetables out earlier so people can plan their work. Don’t cancel or move lectures once agreed

More flexible timetables

Deadlines for assignments for the evening, not 12 noon

Sick of frequent timetable changes

Impossible to plan work and makes me look unprofessional, so I get less shifts

On what might be described as the other side of the excel sheet, cost of living support was endlessly mentioned. Interestingly, financial subsidies for essentials like meals and travel, and free essentials once a month or discounts on food shopping were much more likely to be mentioned than raw hardship funds or bursaries – students in our sample are crying out for efforts to get the cost of participation down, rather than being loaned or granted more money to spend on it. And yes, the cost of catering on campus remains a source of real outrage across our sample:

Financial subsidies (meals, travel allowance…)

Offer help such as free essentials once a month or money off a food shop.

The prices of food at campus are ridiculous

Lobby government to grant full-time students NI credits… we cannot achieve ‘paid-up’ status for our years at uni.

It costs money to travel… Would be good to have travel costs paid for by the uni or have some kind of travel card.

One thing that we think is under-appreciated is the extent to which students are prepared to struggle and juggle – but would appreciate some help in doing so. Even in qualitative questions on student at work, our sample respondents frequently raised a desire for mental health events for those struggling to keep up with both their academic and work commitments, practical guidance on managing stress and staying balanced, as well as workshops focused on coping strategies, support sessions between classes to make the trip to campus more worthwhile, and more focus on campus quiet space to focus and catch up on coursework.

And squeezing every last drop of efficiency is called for too – with things like “shut up and write sessions to help students make up for lost time” high on the agenda:

mental health events for people struggling to balance work and studies,

how to cope better with both studying and working at the same time

events, such as shut up and write sessions to make up for time spent working

Make it worth coming to campus by putting support sessions between classes

Our Belong polling has consistently found that institutional empathy and understanding goes a long way – both in terms of what is regarded as “normal” on campus by peers, and in the way in which micro-decisions and support conversations play out. Clearer communication between workplaces and providers are suggested by some, but far more make the simple observation that they would prefer not to be told, principally by academic staff, that working is a mistake. Students at least deserve respect and support for managing both roles, rather than condemnation:

I was made to feel like I’ve done something wrong by working all night by my P[ersonal] A[cademic] T[utor]. It puts me off from asking for their help.

Clearer communication with employers and academic

work passport… to support appropriate workplace adjustments to support learning

encouraging [employers to support students], as although it is a full-time degree… can still do both

Not to be told I shouldn’t be working anyway

But the number one suggestion – both on its own terms, and in the way in which it helps to address everything from work type to travel to treatment – is that there should be more jobs on campus. Students can’t understand why so many jobs – that the university’s marketing says they could do with ease on graduation – are not aimed at and advertised at them.

More accessible, on-campus roles.

Make more jobs available with the university as they pay fairly and working conditions are always good

Better career options within the students’ union… outside of hospitality and elected student officials

Cleaning jobs on campus not food jobs in factories

Anecdotally, budget cuts on “discretionary” spend suggests that, ironically, in many universities student roles in departments are actually being cut. Instead, universities should engage in ambitious discussions with their SUs aimed at matching the sort of earning while learning programmes we have seen in the US, which cover far more professional services and academic support roles than we have seen in any university in the UK.

Looking to the future

Taken together, the results ought to bury the cliches of lazy students sponging from the state. Some of what is required is as old as any widening participation debate – when a realisation dawns that maybe it’s the norms of higher education that need to change rather than wishing that students were as carefree, and frankly rich (both in money and time) as they were in a forgotten past.

Any future review of student finance policy should encompass a view on students at work – however unreliable some of the averages will be, the relationship of student work to available time and income is why the Diamond Review in Wales, the Scottish Student Financial Support review and even the ignored Augar review of post-18 education in England recommendations centred it in their respective calculations.

But on the assumption that no government – the four in the UK included – is about to find the money to nostalgically recreate the immersive “full-time” student experience of the past in a massified system, the urgent task is do what is within a university’s gift to enable students to earn while learn in way that is not harmful for their health. And given that the most popular answer in previous belonging survey work for feeling connected was “spending more time on campus”, the solution may be closer to home than we think.

Few students want to see staff made redundant. But if, over time, more of what a university does can be delivered by the people that said university is partially preparing for the labour market, it is clear that there would be benefits that go substantially beyond pocket money for leisure time – and will extend to allowing students to spend more of their time actually learning, rather than merely earning.

Click here to view and download the full deck of findings.

At the Secret Life of Students on Tuesday 18 March we’ll be debating these findings and their implications for the future of the full-time student experience. Find out more and book your ticket here.

The next wave of Belong will focus on student health and take place in early 2025: drop us a line to find out more about how your SU can get involved.

Very interesting article. As someone with a partial role as personal tutor this was an eye opener. All VCs should read this.

Also unis should remember that once upon a time they had a duty to ensure both staff and students should be properly fed..

Of course, you could employ an art student to do the graphics, rather than Gen AI? Every little helps. 😉

I think the solution is obvious. We should reduce the number of undergraduate and post graduate students by 50% and get those who are prevented from going to University to take up an apprenticeship. This would provide an additional 250,000 people a year with employment and free part time education. The additional working learners (apprentices) would be able to work from home and not need to pay rent and would probably have cheaper and shorter journeys. They would not have to take out loans to study or need loans for maintenance. They would not run up debts of over £60,000… Read more »

I found this a very interesting read. I’m working on thematic analysis of open responses from students on their use of financial support, which provides (among other things) some information on attitudes towards – and purposes of – savings. For example, some students talk about building up a small ‘safety net’ in case of emergencies, and others of saving towards the near future such as next year’s housing deposit or tiding over the gap between graduation and finding a job. I’ll be doing further investigation of this data in the coming months, and hope to be able to contribute to… Read more »