Over the past year or so I’ve been pleased to be invited to numerous student course rep conferences, I’ve facilitated a number of reviews of student engagement systems, and I’ve appeared at a number of events where student ambassadors or volunteers have been speaking.

On paper, this is not exactly what I might call “core business” – but not only are these bits my favourite part of this job, they are hands down the most useful and rewarding elements too.

There’s something about speaking to those that are holding down their degree, a couple of part-time jobs and a student rep role simultaneously that really brings higher education to life – and reminds me that whatever the level they’re held at, none of the policy discussions matter unless they impact on actual people.

More often than not – either as exercise or just as a conversation starter – I’ll 1) interrogate the motivations that drove a student rep to do what they’re doing, 2) check what the experience has been like versus the expectation, and 3) identify if there are frustrations or barriers to being successful in the role.

In another piece that I’ll get around to writing at some stage, I’ll share some of my conclusions about how that quality assurance thing that we tell ourselves course reps are doing isn’t really happening – and try to work out whether that horse is dead or just needs to be flogged in a different way.

As you’ll have noticed, questions 2 and 3 above are gateway drugs to question 3. But what I hadn’t noticed until I was at a thing a few weeks ago was some of the commonalities in the answers on motivation, and some of the rich diversity in the answers on experience.

So on the train back, I started frantically trying to find the photos of flipchart paper and the scribbles in the notebook to see if I was just delirious or on to something. And I have exciting news.

Give me your heart gimme gimme

At the start of the academic year, sometimes we ask students who among them would like to be stiffed with “dealing with students’ problems on the course”. No wonder nobody puts their hand up.

Sometimes, for returners, we’ve started that process earlier – asking students who’d like not only to deal with students’ problems on the course, but also to navigate a baffling online election system too.

In either event, many of us insist that only one person can undertake this role. Sometimes five people put their hand up, in which event we say to those brave enough to do so that the enthusiasm of four of them is somehow surplus to requirements.

Whether it’s a balloon debate, an online ballot, a paper scissors stone tournament, a coin toss or an awkward process of whittling hands down until the whitest and most middle class hand is left, we then insist on staging some kind of competition for a role when the research says that a public competition is what puts those least likely to hold those positions off from volunteering for them.

So in that context, what is first interesting is the answer to the question about motivation. Because now I look back, there’s a commonality I never spotted before. It might be that the keenest ones or the ones that become full-time SU officers were “into” the idea of quality assurance or pedagogy or curriculum. But the things that thread the majority of their motivations are not that at all. They are service, and connection.

With strikingly few exceptions, when they’re asked about why they put their hand up, it’s about helping, or giving. They talk about wanting to get to know others, and to get others to get to know each other too. They betray a desire to foster community on their course, to make others feel welcome or capable, and to make their experience better through others.

They don’t all say that they wanted to be an amateur community worker. Some frame it as being the person that will raise discomforts and questions about the course on behalf of others. Some describe themselves as the social butterfly, making groupwork happen and ensuring that the quiet ones are included in the group chat.

Some express their amateur role in the provision of foundational study skills or advisor on the meaning of assessment briefs not in pedagogical terms, but in service terms. Others will describe the rich conversations they have with other students and their lives not in ways that surface insight on outcomes, but on genuine curiosity and care for others.

Some just want to make sure people can relax, and build social connections. The woman I met that was passionate about her IT project, once I dug a bit, was less excited about the IT part and more about the confidence she built in herself and others. The rep I met that thought that talking to others about their mental health would help them devise coping strategies was all about giving something to the course. And the duo that staged their own evening talk with employers “because that’s what good reps do” were not part of a careers strategy, they were just student reps who cared.

They’re so time poor, see

In recent years, especially when thinking about roles that involve time or responsibility, we’ve tended towards throwing the towel in on diversity – telling ourselves that the busy commuter or the student parent won’t have the time to take on the thing with the badge and the reports to write.

Take OfS’ views on course reps, for example:

…a student who chooses a short, professionally-oriented course may have different views about the need for student engagement activities than a student beginning a three-year, campus-based undergraduate course, and providers need to be able to respond to both views.

There’s something in that that is important. We do need either to support the sort of volunteer roles that deliver the student experience better, or find a way to reward them for their time. But it’s also the case that all of my instincts tell me that the poorest are also the most generous – and that includes with their time.

One option increasingly seems to involve the abolition of those sorts of student roles altogether. Because they’ll only be filled by the usual suspects on the usual courses, we identify “diverse” alternatives – focus groups, polling, town halls and surveys, all of which keep the power with the convenor and rob the student body of agency, and the ability to surprise.

But I think what the year has taught me is that neither paying them all a salary nor giving up are necessarily the right choices. What is clear is that just underneath the surface, there’s a whole army of students itching to serve others – to run coffee mornings, facilitate project groups, gather feedback on assessment design, or run a tour of the campus. What would happen, if instead of asking students “who wants to be the rep”, we just asked who would like to get involved in the running of the course – and we said yes to everyone with their hand up?

Maybe one will be become the student that ensures everyone’s read those essential emails, and another will become the one that will make sure those who are joining online feel involved. Maybe one will deliver some sessions on referencing, and another will gather feedback for quality assurance. The key may be to not tell people they’re signing up to some onerous election to do the university or SU’s work on the cheap – but to discover who’s prepared to serve and lead others.

Over the hump

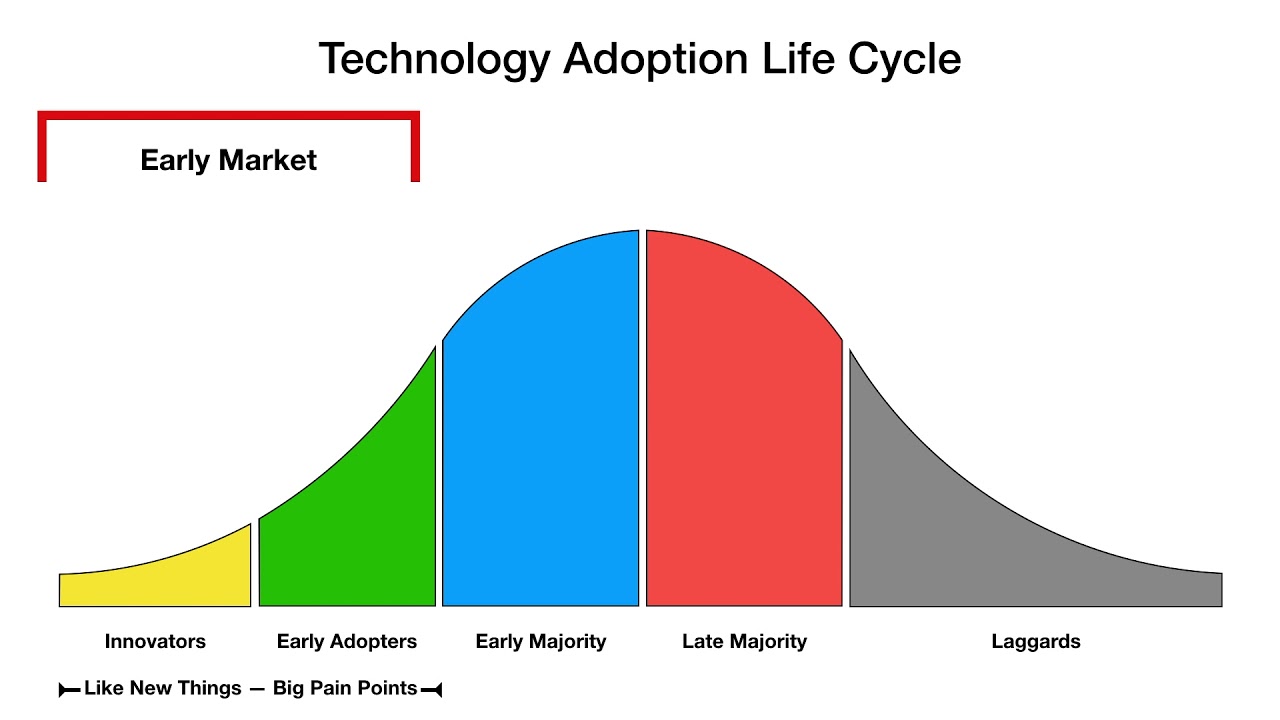

So on the old tech adoption curve, let’s assume that we’re not cutting off our community nose to spite our quality face – and let’s imagine that just by reframing the question and abandoning the sifting, we can get from “1 student per course who hates the role once they know what it is” (innovators) to “a whole bunch of people who are keen to help out” (early adopters). What then about everyone else?

In other blogs on the site, I’ve argued that, particularly in an undergraduate first year or a postgraduate first month, we should make more explicit for students those things that they need to do to become a good student. A blanket intervention early on on academic integrity will always bore those who get it and not deliver for those who don’t, we need the student to understand the deficiency and to have agency on fixing it, and we want any deficiency to manifest in critical self reflection rather than a disastrous grade on an essay.

I would, as I described on the site here, prefer a student to understand their lack of understanding of consent or ethnicity or essay writing before they actually fail at any of those things, and I want them to be motivated to learn the highway code before they crash the car.

But as the “becoming a student” thing – with actual credit attached – starts to ease off in importance, I would argue that something else should taper in. Why should it be possible for a student to leave your university without having had some experience of serving others? Why wouldn’t we require those in the second year of an undergraduate course, or the second month of a postgraduate course, to undertake a role that serves other students?

If everyone had to do it – and there was credit attached – it is true that some would go through the motions, doing the bare minimum for the reflective essay at the end. But vastly larger numbers would do amazing things – building deeper and more meaningful reciprocal relationships with other students and staff, relieving pressure from support services, and displaying ingenuity and creativity in the way that activities and services are carried out.

It’s all happening here

The dazzling diversity of things that I suspect we’d see students do for those compulsory credits would be remarkable. Some would be scouting for student discounts in the area in pairs, reducing the costs of study. Another couple would be chatting to students at other universities to get tips on diversifying the Chemistry curriculum. One would be scouting for volunteers from local employers to be buddies with new international PGRs. One would be doing IAG for potential new students from their country. Another would be organising an informal writing retreat for those doing an extended essay. One would be making English as a foreign language classes happen. And would be delivering conversational mandarin for those keen to connect with Chinese students from the UK.

And don’t tell me they won’t have the time. I don’t buy it. They might not be able to fit a mode of participation that neatly sits around our needs or memories. But if course reps on a shift at work were still taking part in my focus group the other week, I know if we support and frame this right, they’ll get there. And if we can’t, and it gets a bit tough, we’ll understand – but maybe that will help them get angrier about the salami-slicing we’ve done on the “full-time” student experience that is anything but these days.

I’m not suggesting, by the way, that we refuse to remunerate any of the roles I’ve identified. Some of the things students might end up doing in this compulsory credits space almost certainly can and should attract a bursary or a wage. If anything, surfacing them in this way will help us work out which should cost money, and which shouldn’t.

You could go further. Imagine, if you can, what would happen if in year three of the undergraduate course, or period three of that PG experience, if we were requiring all students to serve not so much eachother but the, or their, community – if credits were awarded for a project, or an event, or an initiative that built better bonds between the university and its place. You can fill in the rest from here.

When I look back on the period post-pandemic when I’ve been back on the road, what’s been most inspiring is this mix of service and community that characterises almost all of the students I’ve met. But outside of those course rep conferences, I guarantee it’s going on elsewhere in the student body too. Surfacing it, nurturing it, accelerating it, intensifying it, rewarding it and opening up its educational, social and health benefits to the broadest base of students will do them and the society in which we work immeasurable good.

And anyway – if leading and serving other students improves outcomes, don’t universities and their SUs need to ensure all students can do so?