At one point in my career, I was the CEO of a students’ union who’d been charged with attempting to tackle a culture of initiation ceremonies in sports clubs.

One day a legal letter appeared on my desk – the jist of which was “you can’t punish these people if they didn’t know the rules”.

We trawled back through the training and policy statements – and found moments where we’d made clear that not only did we not permit initiation ceremonies, we’d defined them as follows:

An initiation ceremony is any event at which members of a group are expected to perform an activity as a means of gaining credibility, status or entry into that group. This peer pressure is normally (though not explicitly) exerted on first-year students or new members and may involve the consumption of alcohol, eating various foodstuffs, nudity and other behaviour that may be deemed humiliating or degrading.

The arguments being advanced were fourfold. The first was that where we had drawn the line between freedom to have fun and harmful behaviour, both in theory and in practice, was wrong.

The second was that we’d not really enforced anything like this before, and appeared to be wanting to make an example out of a group of students over which a complaint had been raised.

They said that we’d failed to both engender understanding of where the line was that we were setting for those running sports clubs, and failed to make clear expectations over enforcing that line.

And given there been no intent to cause harm, it was put to us that the focus on investigations and publishments, rather than support to clubs to organise safe(er) social activity, was both disproportionate and counter-productive.

And so to the South coast

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about that affair in the context of the Office for Students (OfS) decision to fine the University of Sussex some £585k over both policy and governance failings identified during its three-year investigation into free speech at Sussex.

One of the things that you can debate endlessly – and there’s been plenty of it on the site – is where you draw the line between freedom to speak and freedom from harm.

That’s partly because even if you have an objective of securing an environment characterised by academic freedom and freedom of speech, if you don’t take steps to cause students to feel safe, there can be a silencing effect – which at least in theory there’s quite a bit of evidence on (including inside the Office for Students).

You can also argue that the “make an example of them” thing is unfair – but ever since a copper stopped me on the M4 doing 85mph one afternoon, I’ve been reminded of the old “you can’t prove your innocence by proving others’ guilt” line.

Four days after OfS says it “identified reports” about an “incident” at the University of Sussex, then Director of Compliance and Student Protection Susan Lapworth took to the stage at Independent HE’s conference to signal a pivot from registration to enforcement.

She noted that the statutory framework gave OfS powers to investigate cases where it was concerned about compliance, and to enforce compliance with conditions where it found a breach.

She signalled that that could include requiring a provider to do something, or not do something, to fix a breach; the imposition of a monetary penalty; the suspension of registration; and the deregistration of a provider if that proved necessary.

“That all sounds quite fierce”, she said. “But we need to understand which of these enforcement tools work best in which circumstances.” And, perhaps more importantly “what we want to achieve in using them – what’s the purpose of being fierce?”

The answer was that OfS wanted to create incentives for all providers to comply with their conditions of registration:

For example, regulators assume that imposing a monetary penalty on one provider will result in all the others taking steps to comply without the regulator needing to get involved.

That was an “efficient way” to secure compliance across a whole sector, particularly for a regulator like OfS that “deliberately doesn’t re-check compliance for every provider periodically”.

Even if you agree with the principle, you can argue that it’s pretty much failed at that over the intervening years – which is arguably why the £585k fine has come as so much of a shock.

But it’s the other two aspects of that initiation thing – the understanding one and the character of interventions one – that I’ve also been thinking about this week in the context of the Sussex fine.

Multiple roles

On The Wonkhe Show, Public First’s Jonathon Simons worries about OfS’ multiple roles:

If the Office for Students is acting in essentially a quasi-judicial capacity, they can’t, under that role, help one of the parties in a case try to resolve things. You can’t employ a judge to try and help you. But if they are also trying to regulate in the student interest, then they absolutely can and should be working with universities to try and help them navigate this – rather than saying, no, we think we know what the answer is, but you just have to keep on revising your policy, and at some point we may or may not tell you got it right.

It’s a fair point. Too much intervention, and OfS appears compromised when enforcing penalties. Too little, and universities struggle to meet shifting expectations – ultimately to the detriment of students.

As such, you might argue that OfS ought to draw firmer lines between its advisory and enforcement functions – ensuring institutions receive the necessary support to comply while safeguarding the integrity of its regulatory oversight. At the very least, maybe it should choose who fronts out which bits – rather than its topic style “here’s our Director for X that will both advise and crack down. ”

But it’s not as if OfS doesn’t routinely combine advice and crack down – its access and participation function does just that. There’s a whole research spin-off dedicated to what works, extensive advice on risks to access and participation and what ought to be in its APPs, and most seem to agree that the character of that team is appropriately balanced in its plan approval and monitoring processes – even if I sometimes worry that poor performance in those plans is routinely going unpunished.

And that’s not exactly rare. The Regulator’s Code seeks to promote “proportionate, consistent and targeted regulatory activity” through the development of “transparent and effective dialogue and understanding” between regulators and those they regulate. Sussex says that throughout the long investigation, OfS refused to meet in person – confirmed by Arif Ahmed in the press briefing.

The Code also says that regulators should carry out their activities in a way that “supports those they regulate to comply” – and there’s good reasons for that. The original Code actually came from something called the Hampton Report – in 2004’s Budget, Gordon Brown tasked businessman Philip Hampton with reviewing regulatory inspection and enforcement, and it makes the point about example-setting:

The penalty regime should aim to have an effective deterrent effect on those contemplating illegal activity. Lower penalties result in weak deterrents, and can even leave businesses with a commercial benefit from illegal activity. Lower penalties also require regulators to carry out more inspection, because there are greater incentives for companies to break the law if they think they can escape the regulator’s attention. Higher penalties can, to some extent, improve compliance and reduce the number of inspections required.”

But the review also noted that regulators were often slow, could be ineffective in targeting persistent offenders, and that the structure of some regulators, particularly local authorities, made effective action difficult. And some of that was about a failure to use risk-based regulation:

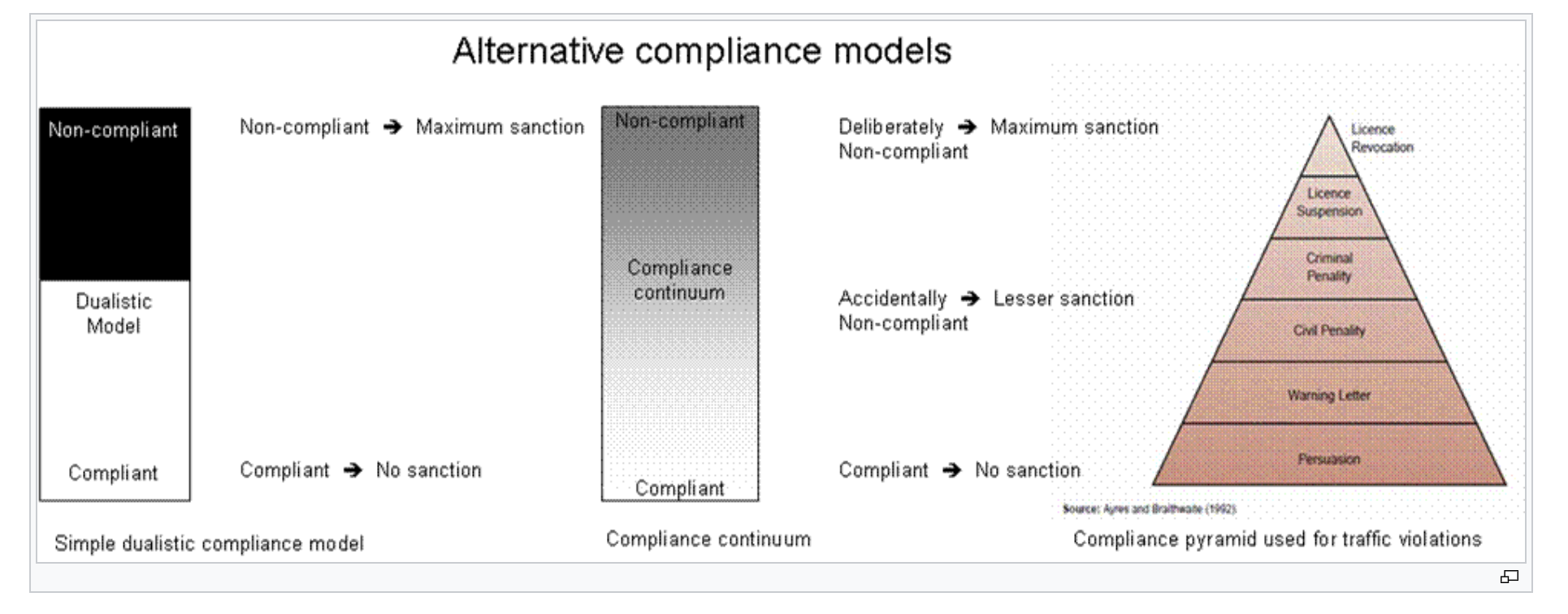

The 1992 book Responsive Regulation, by Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, was influential in defining an ‘enforcement pyramid’, up which regulators would progress depending on the seriousness of the regulatory risk, and the non-compliance of the regulated business. Ayres and Braithwaite believed that regulatory compliance was best secured by persuasion in the first instance, with inspection, enforcement notices and penalties being used for more risky businesses further up the pyramid.

The pyramid game

Responsive Regulation is a cracking book if you’re into that sort of thing. Its pyramid illustrates how regulators can escalate their responses from persuasion to punitive measures based on the behaviour of the regulated entities:

In one version of the compliance pyramid, four broad categories of client (called archetypes) are defined by their underlying motivational postures:

- The disengaged clients who have decided not to comply,

- The resistant clients who don’t want to comply,

- The captured clients who try to comply, but don’t always succeed, and

- The accommodating clients who are willing to do the right thing.

Sussex has been saying all week that it’s been either 3 or 4, but does seem to have been treated like it’s 1 or 2.

As such, Responsive Regulation argues that regulators should aim to balance the encouragement of voluntary compliance with the necessity of enforcement – and of course that balance is one of the central themes emerging in the Sussex case, with VC Sasha Roseneil taking to PoliticsHome to argue that:

…Our experience reflects closely the [Lords’ Industry and Regulators] committee’s observations that it “gives the impression that it is seeking to punish rather than support providers towards compliance, while taking little note of their views.” The OfS has indeed shown itself to be “arbitrary, overly controlling and unnecessarily combative”, to be failing to deliver value for money and is not focusing on the urgent problem of the financial sustainability of the sector.

At roughly the same time as the Hampton Report, Richard Macrory – one of the leading environmental lawyers of his generation – was tasked by the Cabinet Office to lead a review on regulatory sanctions covering 60 national regulators, as well as local authorities.

His key principle was that sanctions should aim to change offender behaviour by ensuring future compliance and potentially altering organisational culture. He also argued they should be responsive and appropriate to the offender and issue, ensure proportionality to the offence and harm caused, and act as a deterrent to discourage future non-compliance.

To get there, he called for regulators to have a published policy for transparency and consistency, to justify their actions annually, and that the calculation of administrative penalties should be clear.

These are also emerging as key issues in the Sussex case – Roseneil argues that the fine is “wholly disproportionate” and that OfS abandoned, without any explanation, most of its provisional findings originally communicated in 2024.

The Macory and Hampton reviews went on to influence the UK Regulatory Enforcement and Sanctions Act 2008, codifying the Ayres and Braithwaite Compliance Pyramid into law via the Regulator’s Code. The current version also includes a duty to ensure clear information, guidance and advice is available to help those they regulate meet their responsibilities to comply – and that’s been on my mind too.

Knowing the rules and expectations

The Code says that regulators should provide clear, accessible, and concise guidance using appropriate media and plain language for their audience. It says they should consult those they regulate to ensure guidance meets their needs, and create an environment where regulated entities can seek advice without fear of enforcement.

It also says that advice should be reliable and aimed at supporting compliance, with mechanisms in place for collaboration between regulators. And where multiple regulators are involved, they should consider each other’s advice and resolve disagreements through discussion.

That’s partly because Hampton had argued that advice should be a central part of a regulators’ function:

Advice reduces the risk of non-compliance, and the easier the advice is to access, and the more specific the advice is to the business, the more the risk of non-compliance is reduced.

Hampton argued that regulatory complexity creates an unmet need for advice:

Advice is needed because the regulatory environment is so complex, but the very complexity of the regulatory environment can cause business owners to give up on regulations and ‘just do their best’.

He said that regulators should prioritise advice over inspections:

The review has some concerns that regulators prioritise inspection over advice. Many of the regulators that spoke to the review saw advice as important, but not as a priority area for funding.”

And he argued that advice builds trust and compliance without excessive enforcement:

Staff tend to see their role as securing business compliance in the most effective way possible – an approach the review endorses – and in most cases, this means helping business rather than punishing non-compliance.

If we cast our minds back to 2021, despite the obvious emerging complexities in freedom from speech, OfS had in fact done very little to offer anything resembling advice – either on the Public Interest Governance Principles at stake in the Sussex case, or on the interrelationship between them and issues of EDI and harassment.

Back in 2018, a board paper had promised, in partnership with the government and other regulators, an interactive event to encourage better understanding of the regulatory landscape – that would bring leaders in the sector together to “showcase projects and initiatives that are tackling these challenges”, experience “knowledge sharing sessions”, and the opportunity for attendees to “raise and discuss pressing issues with peers from across the sector”.

The event was eventually held – in not very interactive form – in December 2022.

Reflecting on a previous Joint Committee on Human Rights report, the board paper said that it was “clear that the complexity created by various forms of guidance and regulation is not serving the student interest”, and that OfS could “facilitate better sharing of best practice whilst keeping itself apprised of emerging issues.”

I’m not aware of any activity to that end by October 2021 – and even though OfS consulted on draft guidance surrounding the “protect” duty last year, it’s been blocking our FOI attempts to see the guidance it was set to issue when implementation was paused ever since, despite us arguing that it would have been helpful for providers to see how it was interpreting the balancing acts we know are often required when looking at all the legislation and case law.

The board paper also included a response to the JCHR that said it would be helpful to report on free speech prompted by a change in the risk profile in how free speech is upheld. Nothing to that end appeared by 2021 and still hasn’t unless we count a couple of Arif Ahmed speeches.

Finally, the paper said that it was “not planning to name and shame providers” where free speech had been suppressed, but would publish regulatory action and the reasons for it where there had been a breach of registration condition E2.

Either there’s been plenty of less serious interventions without any promised signals to the sector, or for all of the sound and fury about the issue in the media, there really haven’t been any cases to write home about other than Sussex since.

Willing, but ready and able?

The point about all of that – at least in this piece – is that it’s actually perfectly OK for a regulator to both advise and judge.

It isn’t so much to evaluate whether the fine or the process has been fair, and it’s not to suggest that the regulator shouldn’t be deploying the “send an example to promote compliance” tactic.

But it is to say that it’s obvious that those should be used in a properly risk-based context – and where there’s recognised complexity, the very least it should do is offer clear advice. It’s very hard to see how that function has been fulfilled thus far.

In the OECD paper Reducing the Risk to Policy Failure: Challenges for Regulatory Compliance, regulation is supposed to be about ensuring that those regulated are ready, willing and able to comply:

- Ready means clients who know what compliance is – and if there’s a knowledge constraint, there’s a duty to educate and exemplify. It’s not been done.

- Able means clients who are able to comply – and if there’s a capability constraint, there’s a duty to enable and empower. That’s not been done either.

- Willing means clients who want to comply – and if there’s an attitudinal constraint, there’s a duty to “engage, encourage [and then] enforce”.

It’s hard to see how “engage” or “encourage” have been done – either by October 2021 or to date.

And so it does look like an assumption on the part of the regulator – that providers and SUs arguing complexity have been being disingenuous, and so aren’t willing to secure free speech – is what has led to the record fine in the Sussex case.

If that’s true, evidence-free assumptions of that sort are what will destroy the sort of trust that underpins effective regulation in the student interest.

I think in this case the clear evidence that universities should not have confidence in the OfS is that they still haven’t said if the current Sussex guidance on trans issues is acceptable. This means no university can be “ready” or “able”, surely, including Sussex who might end up being fined again despite literally asking for guidance on this. And as such the fine is just a hanging threat over any of them which there is no clear way to mitigate against even if due process re policymaking is followed to the letter. It’s an absolute binfire.