Is the current phase of UK university expansion over? There have been rumours for months that this year’s applications cycle was shaping up to be a rocky one. With today’s UCAS release, we now know just how rocky, and why.

The headline figure is bleak: there were 30,000 fewer full-time undergraduate applicants at this year’s January deadline than last year, a 5% decrease on 2016. This is the first time applications have declined since 2012. It will not be spread evenly across the sector: some providers will not even notice the change in their application figures, while others will be at the frontline of recruitment battle, trying every trick in the book to boost their numbers.

The decrease in applications almost entirely wipes out the cumulative increases seen since 2013, something of political significance given that the government has consistently prided itself on university expansion when defending its higher education policies.

Breaking down the decline

UCAS has controlled for multiple factors to understand where the declining application numbers have come from. The 30,000 reduction can be roughly broken down as follows.

| Demographic | Decrease compared to expected trend | Hypotheses for decline |

|---|---|---|

| EU applicants | c. -6,000 applicants | Brexit |

| Nursing applicants | c. -5,000 applicants | Reforms to NHS student finance and support. Decline in older age groups. |

| Older age groups (over 19s) | c. -12,000 applicants | Growing labour market and wages. Decline in nursing applications. |

| 18 year olds | c. -7,000 applicants | Population decline. BTEC decline. |

These figures are estimates of changes compared to trend and the ‘dominant cause’ of the ‘missing’ applicants. There is considerable crossover between each group: half of all applicants aged 25 and over apply for nursing.

There is every possibility that the final picture at the end of the cycle could be even worse. On recent trends, UCAS would expect another 100,000 applicants (16% of the total) after the January deadline, and these typically come from older, overseas, and EU applicants – the groups now in the steepest decline.

Breaking down Brexit

The impact of Brexit will inevitably grab the headlines, and lead to briefing by universities about the dangers of ‘hard Brexit’ and the need to safeguard student movement and possibly other privileges when it comes to student financing.

The 3,000 fewer EU applicants (a 7% decrease) are unevenly spread across the other 27 EU member states. Some of the heaviest numerical decreases some from Romania (-15.1%), Bulgaria (-10.3%), Italy (-11.4%), Germany (10.3%) and Ireland (-17.9%), while some dramatic relative decreases may be attributable to changing agent and marketing activity in different countries as much as it can be to Brexit. Applications from Portugal, Lithuania, Norway (an EEA member) and Denmark are up.

Before the referendum, some vice chancellors were predicting a 60%-70% decrease in EU student numbers if we left the EU. The decline has already begun before Brexit has even happened, and despite funding for courses being guaranteed for EU students starting next year, there does not appear to have been a rush to get in before it that perk is likely to be cut off. Short of a generous (and unlikely) post-Brexit deal, there is every reason to suppose that EU applications to UK universities have begun an inexorable decline.

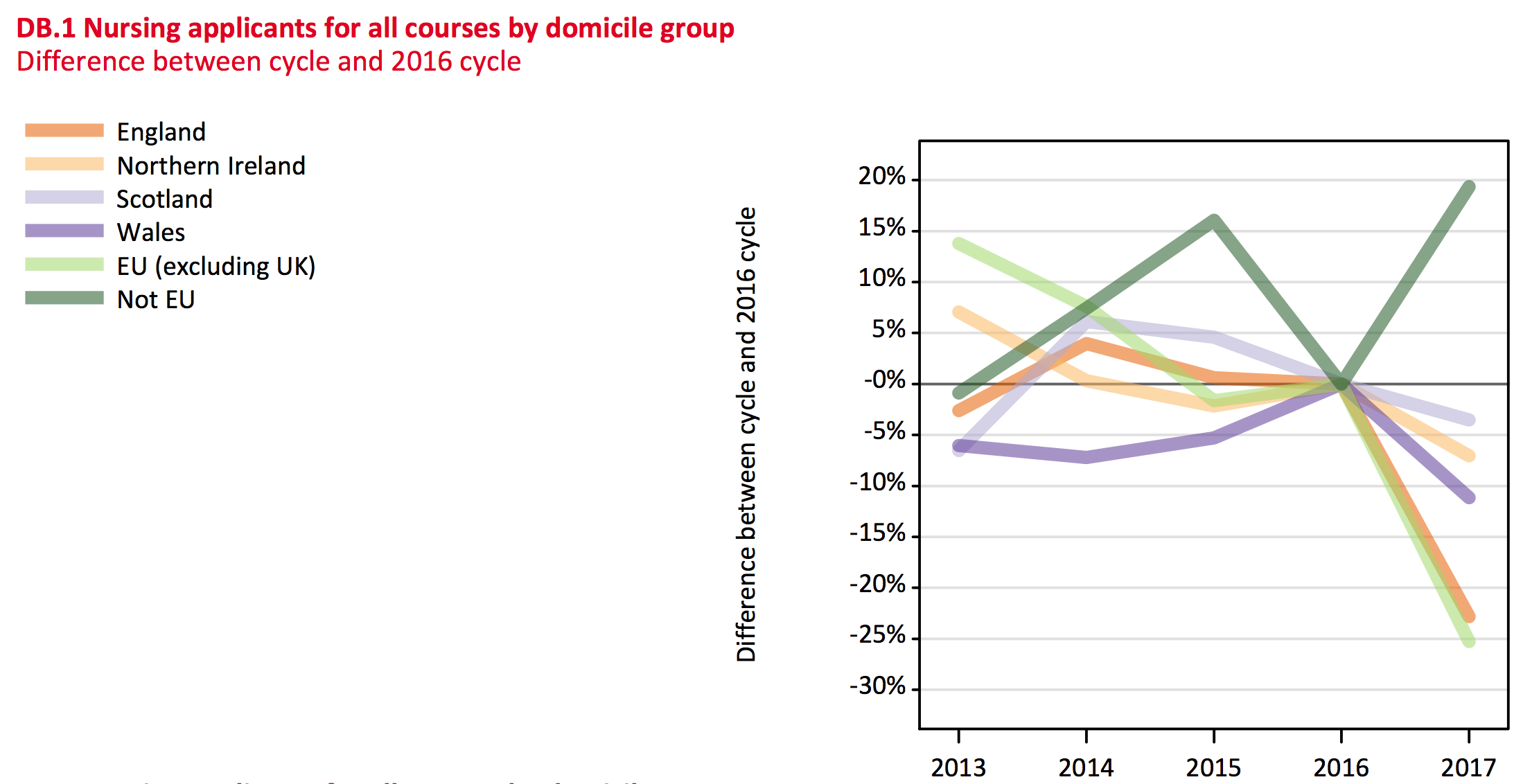

NHS funding reforms bite

Unless universities become dramatically less selective with nursing applicants, the government’s controversial gamble to fund extra nursing and allied health profession places through converting grants to loans does not look set for success. Nursing applications have fallen 23%, and by 29% for those over the age of 21 (a significant proportion of the student nursing population).

When controlling for the broader decline in applications from older students, UCAS estimate that the overall fall in demand for nursing courses ‘as nursing’ is roughly 10%. UCAS suggests this is concurrent with their hypothesis – formulated during the decline in applications in 2012 – that a £1,000 increase in fees leads to a 1% decrease in applications.

Lifelong learning in freefall

We will explore ambitious new approaches to encouraging lifelong learning, which could include assessing changes to the costs people face to make them less daunting; improving outreach to people where industries are changing; and providing better information.

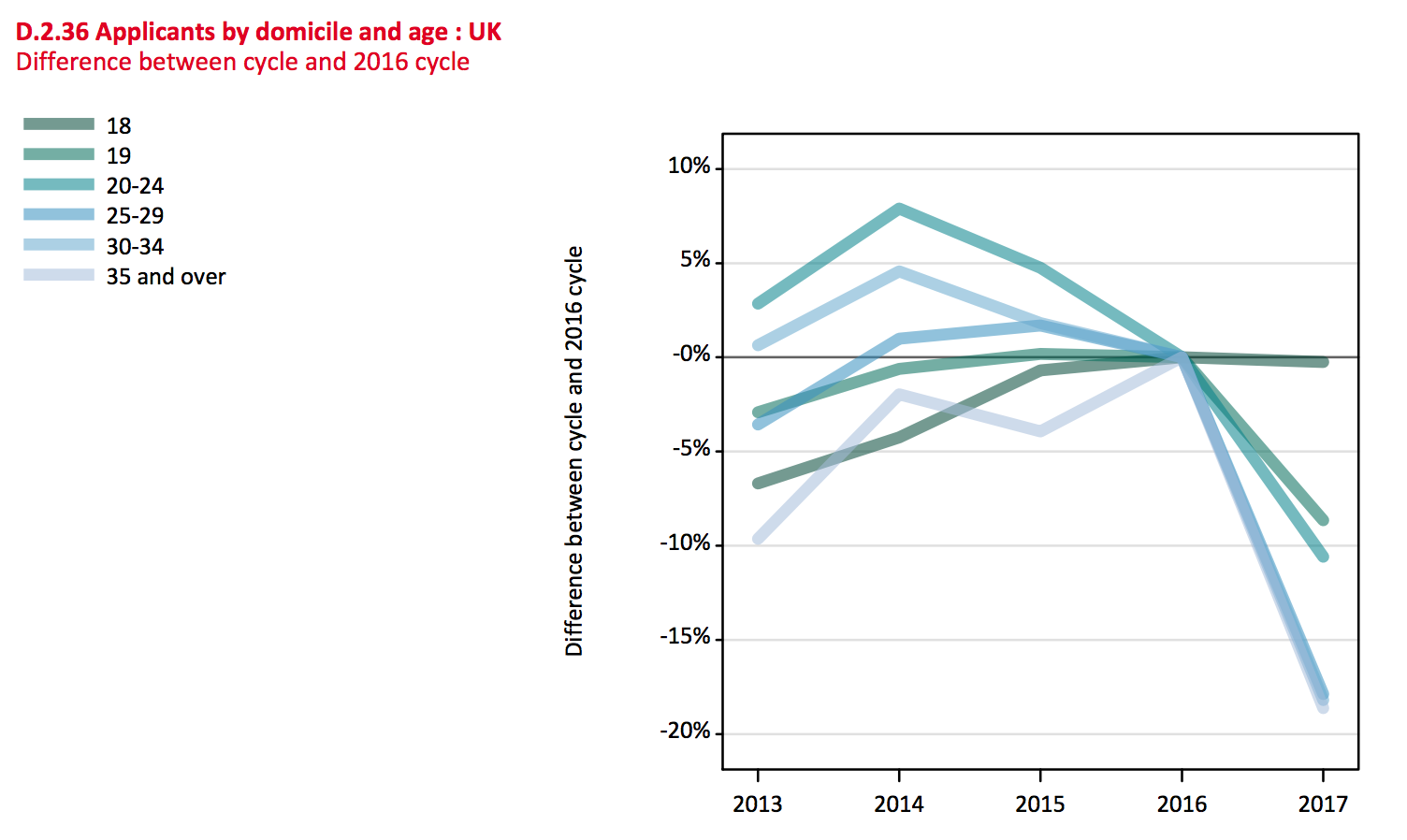

So reads the government’s recent Green Paper on industrial strategy. If this year’s application figures are anything to go by, such ‘exploring’ will need to begin quickly. Applicants to full-time undergraduate courses by over 25s have fallen by 18% this year, a reduction of 10,200.

Much ink has been spilt in recent years on the long-term decline in adult and part-time education in both further and higher education. This year’s accelerated pace of decline will only increase the urgency of that conversation.

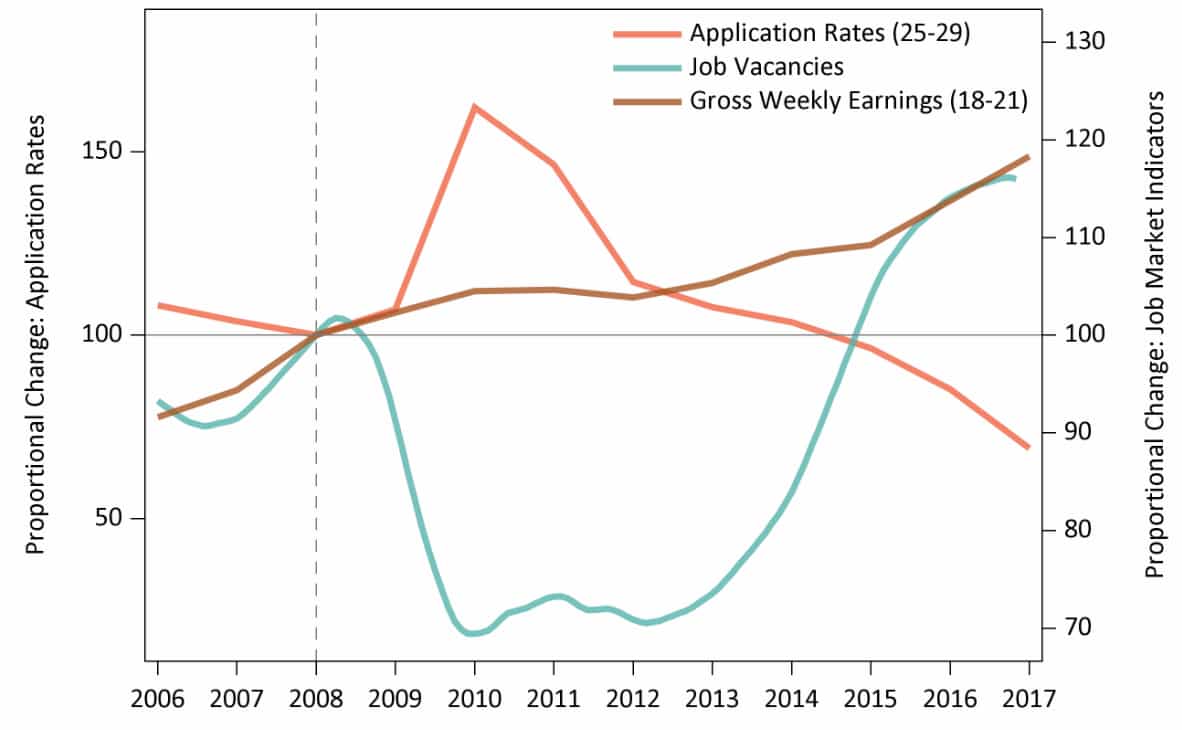

The trend is evidently tied to the decline in nursing applicants, which as noted above, form half of the applications from over 25s. However, UCAS also suggest that changing labour market trends are also closely tied to demand for higher education from adults. Following several years of job growth, the last couple of years has seen a brief increase of living standards and gross wages that may be tied to reduced demand to ‘upskill’. The below chart shows how clearly older demand is associated with labour market strength.

Demand for higher education from adults reached a peak in the last recession. Perhaps one saving grace of any Brexit-induced recession is that this part of the applications market could be revived. Small comfort indeed.

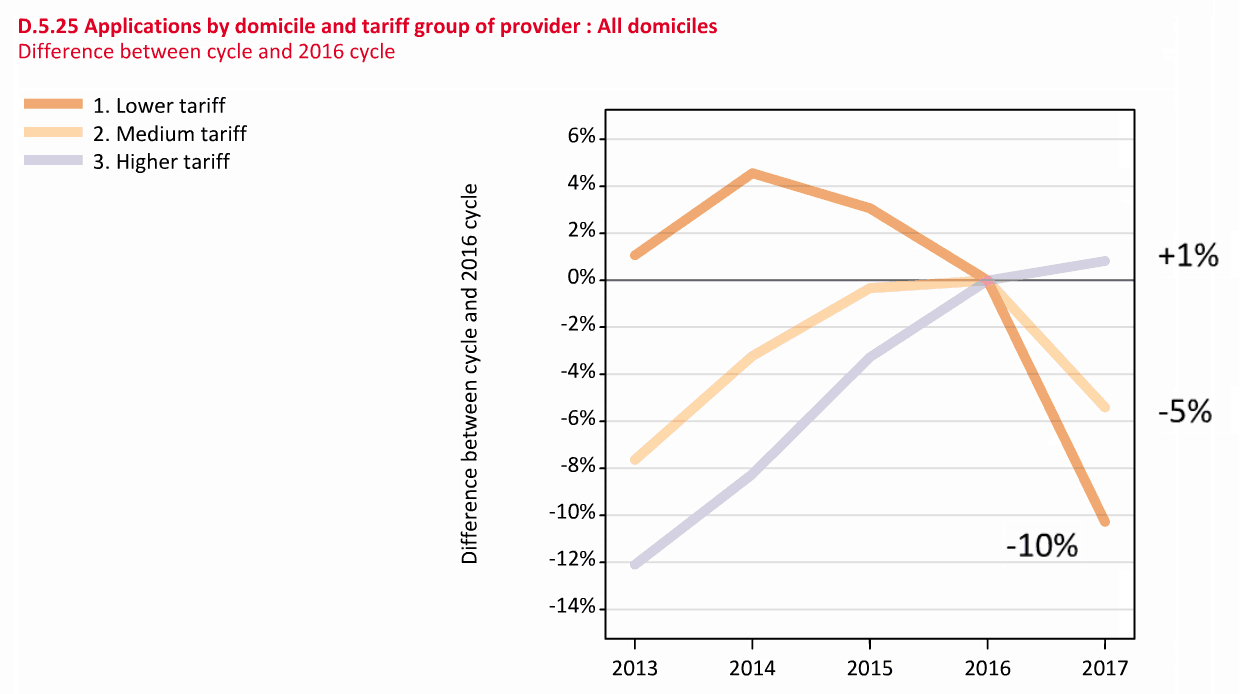

Lower tariff providers hardest hit, especially when it comes to 18-year-olds

The compound effect of all the above trends – as well as underlying trends in the shape of the applicant pool – is that the squeeze will be felt hardest by low tariff universities, and perhaps some in the medium tariff group. High tariff universities, particularly those that rely primarily on 18-year-olds and/or do not deliver nursing, will be best placed to take a hit to EU and international recruitment. Others may not be so lucky.

Low tariff providers are some of the most likely to teach mature students, and many have very large nursing and allied health provision. Yet there is also a squeeze on their school-leavers provision. This goes beyond the much-remarked-on demographic decrease in the 18-year-old population, and the data shows that the application rate of 18-year-olds (i.e. the number of applicants as a percentage of the population) is close to flatlining.

UCAS suggest that this is because of a decline in the number of school leavers holding a BTECs – a significant growth area for lower tariff providers from 2012 to 2015. Another possibility might be the noticeable drops in 18-year-old applications from Northern Ireland and Wales, which stand out from changes across the English regions and Scotland.

Finally, some consideration should be given to whether the transition from maintenance grants to loans for all English students with lower household incomes might be a dissuasive factor, both for 18 year old and older applicants. However, this would be expected to show in a greater rate of decline from the most disadvantaged applicants – today’s release shows that the squeeze has hit evenly across all socio-economic groups in England.

Growing pains

Though the 18-year-old full-time undergraduate market is still healthier than it has ever been, most universities cannot exclusively survive on it. A declining 18-year-old population, combined with a declining 18-year-old application rate, is only the first in a cocktail of risks to the sector’s overall demand pool. Beyond Brexit, nursing, and declining demand for lifelong learning, growth of non-EU full-time undergraduate applicants has flatlined this year and could be ready to decline; it is already falling in significant markets including Nigeria, Malaysia, and Canada.

Market compression will also kill David Cameron’s target to increase the number of black and minority ethnic (BME) students by 20% by 2020. A worrying knock-on effect of the decline in mature and nursing applicants is that while applications from black 18-year-olds remain steady, overall black applicant numbers are down by 10%.

There is also a danger of market contraction becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy as a narrative takes hold that young people are ‘rejecting’ university, perhaps in favour of apprenticeships. This is fashionable for broadsheet columnists but also entirely incorrect. Despite all the noise made about these, apprenticeship numbers – particularly for school leavers – are growing at a snail’s pace: they are still lower than in 2011, and are overwhelmingly at level 2 (GCSE equivalent) and level 3 (A Level and BTEC).

It is also possible to over-focus on hits to EU and international recruitment, two policy areas in which the priorities of education policy will inevitably get lost.

Rather, the most worrying trends are in those areas where educationalists and education policymakers have far more control: health education and lifelong learning. It was Universities UK that recommended reform to NHS student financial support after all.

Declining applications in both adult and health education represent a fundamental failure of our funding and qualifications’ systems to provide the country with a vital economic and social service of tremendous public value. Despite the inevitable shouting match over Brexit, it is these areas where urgent action must – and can – be taken.

You can rind the UCAS data release in full here.

All charts from UCAS.

The time to judge the impact of apprenticeships will be after the apprenticeship levy begins in April this year. Most employers are waiting to implement changes to their apprenticeship recruitment strategy, at any level, until such time as they can use their digital account funds.

tag:twitter.com,2013:885401000177266688_favorited_by_80361783

Martin McQuillan

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885401000177266688#favorited-by-80361783

tag:twitter.com,2013:885401000177266688_favorited_by_431437050

Andy Westwood

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885401000177266688#favorited-by-431437050