Here on Wonkhe we’ve been trying to piece together the Covid puzzle as best we can over the past few months – asking questions and raising concerns to try to help the sector try to get ahead in its thinking.

It’s probably fair to summarise a lot of the recent material as follows. We reckon that there is a significant risk that higher education could amplify local and national transmission of Covid-19, and that this requires better oversight.

One of the frustrations, though, is that we’ve been doing that as a sector without much actual input from “science”. We had an indication from SAGE back in July, an intervention from Indie SAGE last month, as well as one by the BMJ. But while that initial SAGE work identified some of the concerns, we didn’t get much of a sense of the risks.

You’ll recall that that SAGE work in July included the news that a SAGE/Department for Education (DfE) subcommittee was being formed to consider the issues in detail. Now a paper from that task and finish group has been published. Its first bullet:

There is a significant risk that higher education (HE) could amplify local and national transmission, and this requires national oversight.

There are some other important headlines:

- It is “highly likely” that there will be significant outbreaks associated with HE, and asymptomatic transmission may make these harder to detect.

- The sub committee says that outbreak responses will require “both local plans” and “coordinated national oversight and decision-making”.

- The committee argues that it is “essential” to develop clear strategies for testing and tracing, with “effective support to enable isolation”.

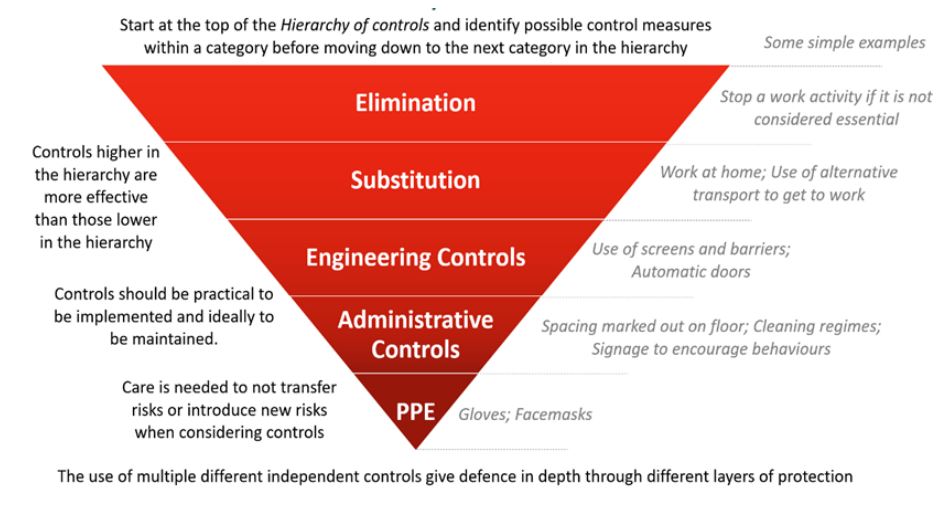

- Provisioning education safely needs a “hierarchy of risk” approach that includes reducing in-person interaction, segmenting students, and environmental controls like ventilation and the use of face coverings.

- Accommodation and social interactions are labelled as “high-risk” environments for transmission and so there need to be strategies to mitigate transmission risk.

- There need to be “specific strategies” to consider the wider physical and mental health of students and staff.

- And communication strategies are a “critical part” of minimising transmission risks- but co-production with the staff and students who will be affected by it is crucial.

It’s a long paper and deserves reading in full, but here we’ve picked out some of the more noteworthy aspects.

Santa’s amplifier

First a look at the “amplifier” problem. The issue here for the committee is that our sector collectively creates a large number of connections – within universities, around communities, across the UK and internationally. It says that a “critical risk” is a “large number” of infected students seeding outbreaks across the UK, influencing national transmission.

The good news is that given the current numbers, the committee reckons that there is a small risk of this “outbreak amplification” problem at the beginning of term (although there’s a couple of weeks to go, and a number of student cities look to have rapidly rising infection rates). The issue the committee is concerned about is that if there is substantial amplification of infection in higher education settings, there is a more substantial risk at the end of term.

It says that epidemic modelling within higher education institutions (that this committee has seen, but the rest of us haven’t seen) suggests that large outbreaks are possible over a time period of weeks, and so could peak towards the end of the term. The “peak health impacts” of these new infections and outbreaks they set off would, it reckons, coincide with the Christmas and new year period – posing “a significant risk to both extended families and local communities”. That risk is marked as “high confidence”. Ouch.

The more worrying bit is that the detailed part of the paper seems to assume that by and large, “away from home” students arrive in a university city at the start of term, go home at the end and maybe pop back for a reading week. I’ll never stop being amazed at how the “boarding school” model of higher education translates literally into assumptions about “boarding” and “boarders”, but I’ll just say this – anyone who doesn’t realise that a substantial percentage of “away from home” students live within the region and go home almost every weekend hasn’t spend enough time talking to students recently. Boarders and commuters is not a binary.

That national Christmas nightmare scenario isn’t the only story. The report also thinks that higher education settings are likely to experience internal, university-wide transmission and influence local transmission in communities. This “spill-over” depends on institutional characteristics (size, location, campus vs city etc), how successful student behaviour initiatives are and the level of integration with local populations – but it’s a real risk.

Do students spread Covid-19? There is “no strong evidence” that those in our sector’s demographics play a smaller role in transmission than adults in the general population, and in fact evidence suggests that there are a “higher proportion” of asymptomatic cases among younger age groups – and so cases and outbreaks are likely to be harder to detect among student populations. Crucially, outbreaks may therefore “be large and widespread before they are effectively detected”.

Oh, and one additional planning point – the committee says that universities may have to adapt elements of their provision at very short notice and so at the very least the following possibilities for outbreaks should be assumed and planned for:

- A large-scale outbreak which may result in substantial restrictions implemented at a local level that impact on HE activities;

- A localised outbreak associated with student accommodation, either halls of residence or houses of multiple occupation;

- A localised outbreak associated with a particular student/staff cohort or academic department;

- Multiple outbreaks in different HE settings, or particularly large-scale outbreaks, that could have significant impact on national transmission.

It’s worth remembering here that if that recommendation ends up in formal DfE advice, once you “cut and shut” it with OfS’ advice on consumer law that says:

Students will need to understand what a provider is committing to deliver in the current circumstances and in different scenarios, how this will be achieved, and the changes that might need to be made in response to changing public health advice, so that they are able to make informed choices”

…we end up with an even more complex situation for planning teams to handle.

Responsibilities

One of the main themes of our blogs over the past few weeks has been about who coordinates and takes responsibility for all of this – and these issues have been picked up.

First of all it argues that a national, coordinated outbreak response strategy should urgently be put in place to link government, the National Institute for Health Protection (NIHP), universities, local public health teams and local authorities to monitor the incidence and prevalence of infection associated with higher education – and take appropriate actions.

This response, it says, needs to define actions and responsibilities across the range of eventualities – including what it says should be a “clear approach” for how data on cases, clusters and outbreaks should be reported, and how this information is communicated between higher education providers and NIHPs – another issue we’ve been discussing on the site.

There’s a particular worry about the end of term – the argument here is that the national work should include plans to “manage” migration somehow in December, as well as managing the response to different levels of outbreaks associated with individual universities.

Testing times

It’s hard to underestimate how important a part of puzzle testing is – and this is reflected here. The paper notes that a critical control against transmission is that people with symptoms isolate, are tested and engage with contact tracing – and so it says that a national strategy defining key principles for additional testing in higher education should be developed that can be adapted and implemented locally.

The section goes into some detail on an approach that moves away from the idea of universal, regular, compulsory testing, and instead veers towards targeting capacity – making it very easy to access, and throwing extra testing at specific tracing efforts – things like “if we find a case in a halls of residence, chuck a mobile testing unit at it and test people intensively”, basically.

What it doesn’t do in any detail is address the question of students being motivated to get a test quickly in the first place – which we figure could be a fatal flaw in a system that is about voluntary testing capacity.

Teaching and risk

This “hierarchy of risk” thing is quite a big one. What it’s basically saying is that to determine whether something should happen, and if so the mitigations to allow it to happen safely, you’ve got to consider the different modes of transmission, the duration of exposure and the vulnerability of the people concerned – potentially complex stuff at this late stage.

It’s like doing risk management in 3D, and should, it says, include consideration of:

- The learning outcomes of courses (or broader educational benefits of an activity)

- Student and staff wellbeing

- The transmission risks associated with different activities

- The risk of amplifying transmission in the community

…to determine the appropriate balance of online and in-person interaction involved in any given activity.

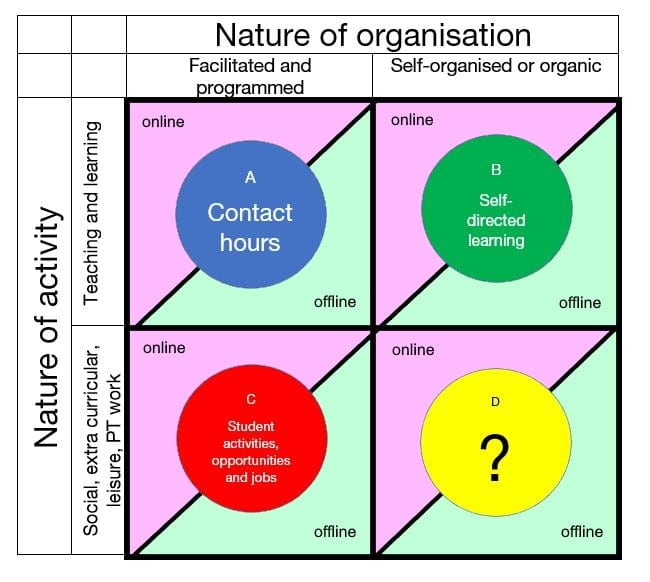

From https://wonkhe.com/blogs-sus/what-are-students-going-to-do-with-their-time/

Put another way – for anything in Box A or C (or facilities you might offer for Box B and D), you should take into account the activity, the list above, the demographics of those involved, and the timing (when in the day, week or even term).

If that sounds complicated and overwhelming, the document has a sort of short cut:

There is strong evidence that reducing in-person interaction is an effective way to limit transmission and so delivery of activities online, especially for larger groups is a key mitigation”.

The paper says that “modelling insights at the level of HE settings” (again we’ve not seen these) suggest that infection dynamics are dependent on complex interactions between study years, courses, accommodation and social networks – and so tries to suggest that bubbling (called “segmentation” in SAGE terminology) is attempted, although this is much easier modelled and press released than it is delivered in practice.

This bit also rehearses some of the mitigations that address aerosol, droplet and surface transmission in previous and wider guidance – avoiding crowded indoor spaces, ventilation, face coverings, PPE and cleaning.

What the paper doesn’t do is say “reduce in-person interaction down to as little as possible” as Indie SAGE did – but it gets quite close, and adds that level of risk analysis complexity if you’re determined to do it.

And its big flaw is that it has a “risk assess the things you organise” approach, rather than a “what will students be doing all week if we don’t provide it, and how can we reduce the risks of that” approach. It’s analysis that has the student life telescope the wrong way up.

(It’s similar to this problem. The current quarantining advice exists in a context – that it’s mainly about people coming back from holiday and that those people are sparsely distributed around the UK. It doesn’t assume that there could be very highly concentrated numbers of international students arriving into the UK at the same time into the same HMOs or halls, all using the same Tesco Metro. Once you know that, you amend the advice for the landlords and the supermarkets. But in the main so far, UK higher education has been implementing advice for other sectors.)

The closest the paper gets to this is to stress that “care needs to be taken” not to inadvertently increase risk by driving staff and students into riskier environments:

Closure of canteens or student bars (rather than improving their COVID-security) will be counterproductive if this simply makes students congregate in cafes or bars that are less Covid-secure.

It says this in the context of evidence from other contexts (e.g. hospitals) that suggests that staff who adhere well to protective behaviours in a formal setting can then engage in risky behaviour in informal settings.

I have a feeling that the number of hours that health service staff are at work for (people who are literally immersed in the pandemic) is very slightly higher than the number hours students are going to be allowed to be on campus for…

Houseparty!

The section on student accommodation and socialising is fascinating. The committee clearly regards some of the stories coming out of North America as instructive – the paper is full of references to them – and states that there is “clear evidence” of outbreaks linked to student housing, social activities and settings like bars. It’s reassuring to see lots of the issues previously highlighted picked up here.

There is plenty of stuff we’re familiar with by now – residents in university accommodation should be segmented (again, much easier in theory than in practice), “clear communication” to students about transmission, and actions to take in response to confirmed or suspected cases in their accommodation is described as essential.

Universities are advised here to put in place strategies to support students and staff who are required to isolate, including by providing dedicated accommodation to minimise ongoing transmission in halls of residence or shared housing. That will pose a problem for some providers who own very little stock these days, and even for those that do it’s quite late to reserve the space if you haven’t already.

On social activity, the report highlights a study of influenza transmission at Shinshu University, Japan which showed that sharing classes or laboratories was for about 10 per cent of transmission, with another 10 per cent or so through socialising with friends and 20 per cent through clubs and societies (a third were unknown, and the rest a mixture of lodgings or apartments, employment, activities in the city, bus or train travel, and family).

It’s not unfair to observe that much of the sector’s efforts have been on tightly controlling and sharing classes or laboratories, with much less focus on socialising with friends and clubs and societies.

As such it says that it is “particularly important” to promote “responsible behaviours” relating to social events which may require “multiple strategies” for communication, engagement and enforcement. And these, it says, should include commuter students and students with part-time jobs, given these represent points of contact between universities and the community.

There’s a distinct whiff of magical thinking about this section – the bubbling it suggests won’t really work (especially not at this late stage), and the jury’s out on whether the messaging and behaviour code stuff will work on a group of people that a) have been sold freedom b) have been cooped up at home since March and c) believe they aren’t really at risk from the virus.

And again, there’s a real danger here surrounding the level of understanding on and thinking around where we expect students to be all week if it’s not on campus, not in each other’s houses etc is poor. An under-reported feature of a number of the American cases is, for example, household visit transmission – a big feature of the UK lockdown areas – and this probably needs much more thought in a UK context.

Most of the UK has spent the last week debating whether to spend all day in a house or an office. In the few days we have left we might usefully ask ourselves how students might be spending their week (given their cramped living conditions and lack of campus facilities), and see if there are ways we might be able to make that more bearable.

Only the lonely

What is helpful is a recognition that if students do “behave” and spend lots of time alone in their rooms, there may be a major mental health risk, alongside a wider collection of health risks – although we veer here into “you must think about things” territory, with a recommendation that notably fails to allocate responsibility (particularly for finding the money):

It is important that provision is made to support mental and physical health of staff and students, beyond Covid-19. Additional support is likely to be needed in the HE sector to provide capacity beyond already stretched mental health services.

Oh, and don’t forget about the flu. Not freshers’ flu – the actual flu. “There is likely to be co-infection with other viruses including influenza over autumn and winter”, and so maximising the influenza vaccination programme to protect at-risk groups in higher education settings will, it says, be important.

Co-production

Finally, having not coproduced any of the modelling, science or assumptions with students, there’s material in here that is vivid on the idea that rules will be adhered to if they are “co-produced” with the staff and students who will be affected by them.

It says:

- Guidance should promote the salience of the group’s identity

- Promote safe behaviours as one of the norms of the group

- Ensure that student organisations lead in promoting COVID safety.

- Policies and messages should take into account the diversity of social and cultural backgrounds of students and staff.

- Obtaining maximum support and adherence will require that messages are tested with people from different backgrounds to ensure that wording and concepts are understood, reinforced by people who are trusted, take into account the issues that people from different cultures may face (e.g. religious observances, typical living arrangements), and are sensitive to pre-existing attitudes towards health promotion and health communication (high confidence).

That’s all very well, and all very sensible, but a) the text later stresses the need to have consistency in a large city between different institutions – so what, unique, is really being “produced”, b) it ignores how often the national and regional rules seem to change which you’d ideally be incorporating it all, and c) all of this really is much too late now.

The good news is that those itching to launch an authoritarian crackdown are advised against it. “Disagreements, mistakes and transgressions” will happen, and “preventing anger, confrontation and stigmatisation will be important”. Students and staff should be encouraged to adopt a “supportive attitude” and “engagement, explanation and encouragement” should be considered for transgressions as well as enforcement.

In reality, that faint whiff of magical thinking may well also be present here. What we need is a sense from modelling of how many transgressors it would take to cause a problem. Even if we’re 95% successful with the messaging, if 5% of students could cause a local lockdown that might change our planning. (My experience as an SU CEO tells me that even a tiny handful of badly behaved students can use up most of the time, bandwidth and goodwill – and that’s in years without global pandemics.)

And again, it really would help if we talked properly and honestly to students about what they will do, and where and when they will do it.

In the next exciting episode

There is plenty more detail in the document not covered here, but we can see where this is going. A significant number of the “universities should” lines are likely to end up in DfE’s revised advice, which we’re told is coming (at the time of writing) towards the end of next week.

And like in the revised Scottish advice. the danger is that a lot of it is framed as “yeah, and you need to think about X” without providing the coordination, time, resource or backup to solve the puzzles that these lines tend to represent.

One thing we’re amazed about, by the way, is the data in use here in the main paper, in appendix A (“Characteristics of Higher Education settings”) and the additional information on HE settings in England supplied by DfE – insofar as it seems to use the very easiest of public data to access. For instance, you’d think they’d be looking at the same term-time address data as DK did, the same internal migration data… they are not. We’re also surprised they are not using data from UCAS at all. DK has a longer reflection on this data quality issue on Wonk Corner here.

It would be easy to read it all and say “oh but this is all coming very late”, although others might argue that none of the issues are new – they’re just in one handy document. And in some senses, the questions are the questions that have been there for some weeks now:

- Will the advice on clarity of responsibility, coordination and data in local areas and nationally get picked up – or will all of this be “dumped” on providers?

- If universities now decide that some of the activity previously announced is just too risky (or complicated to assess for risk), what will be the implications – legally (consumer law) morally (isolation) and from a risk point of view (what if we’re just moving the problem off campus and into the community?)

- Are universities expected to suddenly pick up and deliver on all of the things that could complete the journey from here to DfE advice with no time, no additional money and an A level crisis still reverberating around the sector?

- Shouldn’t there be more visible pooling of problem solving capacity and city/region coordination?

- If the risks here are all so complicated, surely they are for students too – how are we cushioning or mitigating their risks of enrolment?

- Why is all the co-production with students over “communication” rather than the science and modelling itself? Won’t our approach – of treating students like lab rats where dangerous assumptions are made about lifestyle and behaviour – end in failure?

- And will we ever get to see the modelling upon which this advice is based?

That’s not an exclusive list, of course – and do add your own in comments below.

If this all feels exhausting and overwhelming, it’s probably because it is – and we’ll be seeing plenty of that from students too in the coming weeks which will require maximum empathy from all involved as they express their anger at the realities of all this on social media.

Let’s hope all of this is, in the end, manageable – in all senses. Canadian HE expert Alex Usher (you’ll remember Alex from his blog for us on whether to… reopen campuses this September) had some wise words this week that will hopefully see us all into the new term:

Someone smarter than me on Twitter – apologies, I forget who – made a literary analogy a few months ago to the effect that while in March and April Covid was the plot, since then it has become the scene.

This is a fragile time. Some institutions are financially fragile. And on-campus, professors and students are exhausted and worried for all sorts of reasons. But if we keep calm and support one another, we’ll get through it. Together.