The Department for Education and BEIS have recently announced a programme aimed at “Reducing bureaucratic burden in research, innovation and higher education”.

Bureaucrats of the world unite and build a bonfire of regulation. You have nothing to lose but justification for your continued existence.”

(Old saying from the former German Democratic Republic. (Not really, I made it up.))

The three Ministers, in their foreword, comment:

We have been concerned by a major growth in bureaucracy over recent decades, which became particularly apparent for the R&D system during the pandemic, much of which has added limited value or in some cases led to negative behaviours or consequences. Too often administrative activities are a distraction from the core purpose of research and education providers.

We recognise that government has to take its share of responsibility for the growth of that bureaucracy. That is why DfE and BEIS, working with the Office for Students (OfS) and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and DHSC’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) are announcing a substantial reduction in bureaucracy to help focus on what really matters. We have identified significant sources of unnecessary bureaucracy that will be removed immediately, as well as a commitment to a wider reduction of bureaucracy in universities and a system-wide review of the causes of unnecessary research bureaucracy over the coming months. In doing this we want to free up providers to concentrate on delivering the high-quality teaching and research that our economy and society need.

I’ve written here before quite a few times about my concerns about the over-regulation of universities (see for example this from earlier this year and, more recently, this) and therefore, on the face of it, this looks like a welcome development.

Why is this such a big deal? Well, the regulatory burden on higher education has grown hugely in the past 30 years. And, apart from one brief blip – when Teaching Quality Assessment was ended nearly two decades ago – the trend has been relentlessly upwards. Therefore the announcement about reductions in bureaucracy has to be seen as very much a step in right direction. What is on offer then?

Going in the bin?

First up they are asking the Office for Students “to undertake a radical, root and branch review of the NSS”. There has been much comment about this proposal with lots of people celebrating the possible demise of the National Student Survey and others being more concerned about losing a useful tool for focusing on improving teaching and more broadly addressing the concerns of students about their academic experience.

Personally, I would not mourn the loss of NSS – whilst it may have had an initial impact there has to be a better way in persuading universities to focus more on getting student assessment and feedback right.

Moreover, the numbers have been a gift to the university league table compilers, all of whom should be made to work much harder for their money. But, I think the real issue here is that it is really only a modest gain in terms of reducing the burden – a welcome change, yes, but is not going to register that significantly in terms of the total regulatory package reduction.

Secondly, there is the potential change in Data Futures to get us to a more sensible position – having been chasing the fantasy of real time data updates as originally required by the regulator for far too long. Most student data changes infrequently if at all during a year, and therefore real time or very frequent reporting is just unnecessary.

We have moved more recently to something a bit more realistic for this project but it has all been far from straightforward and let’s hope that we can get a clear and rational direction now.

Thirdly, there is a review of TRAC for teaching. This has to be a welcome development and I suspect the removal of this really time-consuming and not terribly helpful process would be welcomed by just about everyone in the sector.

Data dump

We also have a much-anticipated reduction in number of data returns. It is a reduction of two collections, albeit non-trivial, but this still feels like a modest gain given the many hundreds of data returns and other submissions made by universities, not just to HESA but many other agencies and bodies too.

Indeed, it is almost a decade ago now but the Higher Education Better Regulation Group identified 550 lines of reporting required of institutions by professional, statutory and regulatory bodies.

Data does matter though and it is worth noting the view expressed recently by Rachel Hewitt of HEPI on the need for an element of the right bureaucracy to ensure that policy is based on the right evidence – and that there is a need to be cautious about the ending of the NSS and other possible changes:

As I learnt during my years at HESA, good quality data is bureaucratic. There are whole teams of staff in universities across the country whose jobs are to ensure we have robust data about students, graduates, staff, university finances and others. It is entirely fair to critically assess the data Government are using to form judgments about higher education. However, if we want our policy making to be based on evidence, my takeaway from these changes is that we need to engage with what data we do want Government to be working on, rather than only criticising the existing metrics.

It’s a fair point, but it does rather suggest we need to focus our concern on the other 548 lines of reporting (or however many it is now, my guess is a lot more) with which universities have to comply and determine which ones are really needed to provide the evidence base required for effective decision-making.

The R numbers

So much for teaching, there are also some promises about addressing the research regulatory burden too:

UKRI has a clear plan on how to reduce bureaucracy further, beginning with a root and branch review programme starting now to look at UKRI’s approaches to:

• selecting the right things to fund

• assuring the funding is spent for the purpose allocated

• capturing the outcomesUKRI will work closely with key stakeholders to design, deliver and evaluate the impact of these changes to ensure that they result in true systemic reductions in bureaucracy rather than simply moving the burden to another part of the system and without compromising UKRI’s ability to invest in quality ideas, researchers and innovators.

Also the document reports that the Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC) National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has previously implemented a range of measures to reduce burdens on researchers and sets out some further steps it intends to take.

So, it’s looking like we might get a few wins in reducing the burden in the research space too.

A graphic illustration

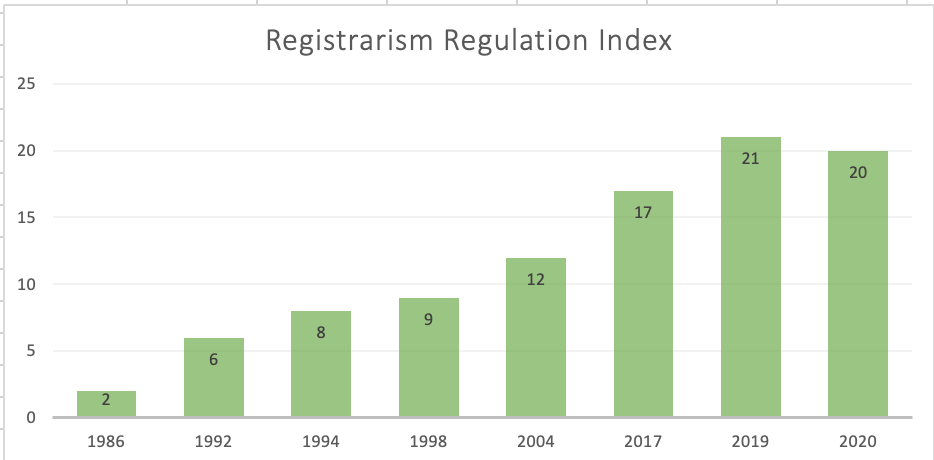

Where does this leave us? Well, you might remember a controversial but impossible to argue with and highly credible and evidence-based graph I’ve previously shared on this topic.

Bearing in mind that many of the changes mentioned in the Ministers’ statement have yet to happen and will be subject to further consultation, all we can do here is speculate. So, my estimate of the total impact of all of these changes, should they all be agreed and fully implemented can be seen in the final bar of this graph. It’s pretty surprising I’m sure you will agree.

What this demonstrates is that we still have a real challenge to reduce regulation and regulation costs a great deal of money. We really do need to address this given the continuing financial constraints on the sector

Do it yourself

The document also contains a rather surprising (to me at least) instruction to universities to get our own house in order:

Government is clear that providers must also play their own part in this: by reducing their own unnecessary bureaucracy, administrative tasks and requirements placed on academics that do not demonstrably add value.

We therefore expect providers to ensure reductions in government or regulator imposed regulatory activity are not replaced with internal bureaucracy. In addition, we want them to go even further to enable academics to focus on front line teaching and research: stripping out their existing unnecessary internal bureaucracy, layers of management and management processes.

This aligns to the OfS’s planned development of its approach to the regulation of quality which will ensure that universities are clear that voluntary codes and guidance do not constitute regulatory requirements. Institutions should consider the extent to which the use of such voluntary material creates unnecessary bureaucracy and prevents academic staff from focusing on core teaching activities.

This echoes the line in the recent paper on the Restructuring Regime (this was only in July) in which the foreword contained a similar and very clear message:

At this time of financial challenges, universities and other higher education providers must do much more to strip back bureaucracy, allowing academics to focus on the front-line…while excessive levels of senior executive pay may have been the focus of criticism, equally concerning is the rapid growth over recent decades of spending on administration more broadly, which should be reversed.

Universities, it is true, can sometimes be our own worst enemies – either internal ‘gold-plating’ of our own institutional processes, overlaying these excessive external demands with even more or offering insufficient challenge or even contributing actively to extending the reach of external regulators. So this, on the face of it, seems a reasonably fair challenge.

However, the vast majority of these additional internal bureaucratic requirements are in fact brought in as a response to external regulatory demands. Likewise, administrative spending is often necessary in order to cope with new regulations and indeed to protect core teaching and research staff from having to engage with them more than is absolutely necessary.

Whilst universities can and should review their own administrative processes what we really need is further reductions in externally driven bureaucracy, very much building on these latest announcements which will ensure that we have a risk-based, proportionate, and comprehensive regulatory system in place that is fit for the future.

This is surely what the sector needs. We are though a very, very long way away from it at the moment. And, despite the latest positive steps, there must be a concern that this was a temporary blip and there is new wide-ranging regulation on the way which will include a major and quite unnecessary focus on free speech in universities. Not only that but there are strong rumours at the moment about the possibility of Ofsted taking on a regulatory role in relation to degree apprenticeships in universities. Again, this is only going to add to the burden rather than reduce it.

Cut, cut and cut again

I would suggest a different approach which build on the welcome announcements from the three Ministers. The current regulatory regime though does not in any way resemble risk-based assessment. Given that higher education is fundamentally a low risk operation we really need to take a step back and look at higher education regulation in the round, accepting that the last substantive piece of legislation, HERA, is already clearly unfit for purpose.

Beyond this more comprehensive review of the regulatory burden, all the way up to HERA, I would suggest that we also need to:

- Discontinue TEF (and abandon any thoughts of subject-level TEF) and explore the elements of the existing suite of university quality assurance mechanisms which can provide strong assurance of quality and standards.

- Look again at our approach to REF (and KEF) with a view to significant streamlining.

- Review the full range of the remit for OfS to ensure it adopts a genuinely risk-based approach to regulation.

- Reduce the wider regulatory controls from FOIA, to CMA, to OIA.

- Review the full suite of data requests – revisiting the 550 or so requirements identified a decade ago by HEBRG with the aim of halving them.

Over the event horizon

University regulation, as it grows and grows, requires universities to spend more and more time and money on compliance. Notwithstanding these latest changes, if the burden of regulation continues to grow and government continues to insist on more direction of and control over university activities we will reach a point where the cost of regulation itself and the expense for universities of complying with the regulation actually exceeds the cost of the activity regulated. Then everything will collapse into a black hole of regulation. It is to be hoped then that the latest changes indicate a real reversal on the part of government rather than a small deviation on the way to the event horizon.

Whilst what has been proposed here then is less of a bonfire but rather more a campfire it is welcome nevertheless. Let’s hope we see more of the regulatory burden going up in smoke.

Thank you, Paul. Another cost of regulation is driving staff who wish to teach and research out of university employment.

I think most pension funds have already collapsed into a black hole of regulation.