Are universities doomed?

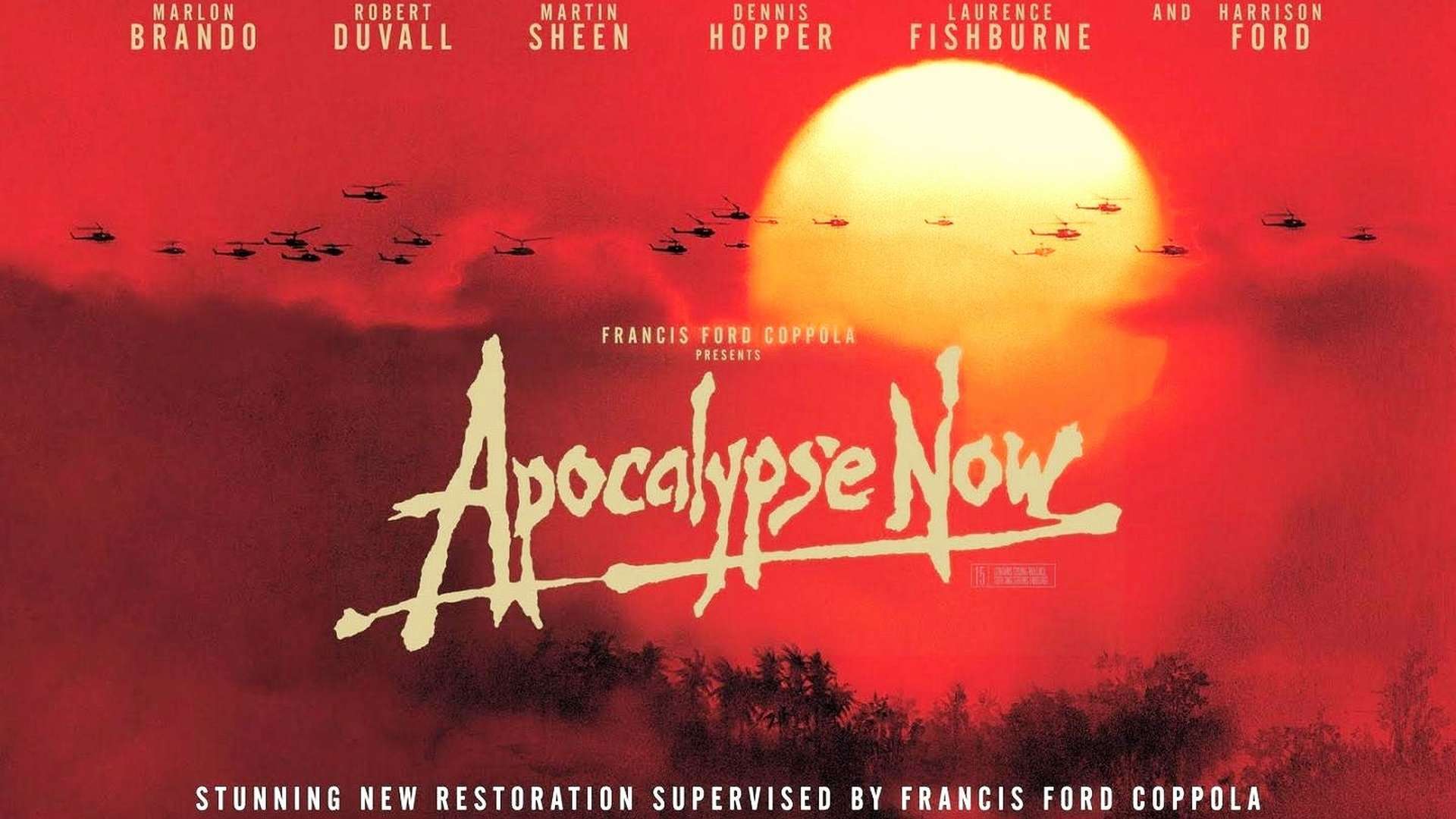

For the latest instalment in the Imperfect University series I wanted to reflect on the fact that there has been something of an apocalyptic tone to many recent pieces on higher education. From the MOOC avalanche to universities “at war” to the “slow death of the university” and all points in between you could be forgiven for thinking higher education is facing imminent disaster.

Post-election this is only going to grow with deep concerns in the sector about what the Conservative government’s actions in relation to visas and the consequences for international student recruitment will be and concerns about the financial impact of EU withdrawal in the event of a negative referendum result. And who knows what else will happen as the cuts begin to bite.

So, is everything just terrible?

Pessimism of the intellect: everyone’s doom-mongering

One early apocalyptic book was published way back in 1997. The University in Ruins by Bill Readings (which I have not read):

It is no longer clear what role the University plays in society. The structure of the contemporary University is changing rapidly, and we have yet to understand what precisely these changes will mean. Is a new age dawning for the University, the renaissance of higher education under way? Or is the University in the twilight of its social function, the demise of higher education fast approaching?

Increasingly, universities are turning into transnational corporations, and the idea of culture is being replaced by the discourse of “excellence.” On the surface, this does not seem particularly pernicious. The author cautions, however, that we should not embrace this techno-bureaucratic appeal too quickly. The new University of Excellence is a corporation driven by market forces, and, as such, is more interested in profit margins than in thought. Readings urges us to imagine how to think, without concession to corporate excellence or recourse to romantic nostalgia within an institution in ruins. The result is a passionate appeal for a new community of thinkers.

Luckily, that community of thinkers has emerged in the years which followed. Less fortunately perhaps they all seem to be as pessimistic as Readings. For example we have Michael Barber and his predictions about major disruption in Higher Education.

His avalanche was going to deliver a revolution. Perhaps:

Our belief is that deep, radical and urgent transformation is required in higher education as much as it is in school systems. Our fear is that, perhaps as a result of complacency, caution or anxiety, or a combination of all three, the pace of change is too slow and the nature of change too incremental.

That’s universities finished then.

Meanwhile Stefan Collini in a review of books by Roger Brown and Andrew McGettigan in the London Review of Books joins the chorus of doom:

Future historians, pondering changes in British society from the 1980s onwards, will struggle to account for the following curious fact. Although British business enterprises have an extremely mixed record (frequently posting gigantic losses, mostly failing to match overseas competitors, scarcely benefiting the weaker groups in society), and although such arm’s length public institutions as museums and galleries, the BBC and the universities have by and large a very good record (universally acknowledged creativity, streets ahead of most of their international peers, positive forces for human development and social cohesion), nonetheless over the past three decades politicians have repeatedly attempted to force the second set of institutions to change so that they more closely resemble the first. Some of those historians may even wonder why at the time there was so little concerted protest at this deeply implausible programme. But they will at least record that, alongside its many other achievements, the coalition government took the decisive steps in helping to turn some first-rate universities into third-rate companies. If you still think the time for criticism is over, perhaps you’d better think again.

However, he has also written a well-received (by some) book – What Are Universities For? – which brings some interesting definitional challenges but seems to avoid the question as the author admits: “Any answer, is bound to be a tiresome combination of banality and tendentiousness.”

Universities at War is a somewhat aggressively titled book by the passionate higher education commentator Thomas Docherty. Reviewed by Mary Evans in the Times Higher it is described as

a cogent critique of authoritarianism within the academy and a stirring defence of universities as what Docherty describes as “secular” places, committed to debates that challenge the enforcement of ever-closer connections between the priorities of the university and those of the wealthy.

Not what you would describe as an optimistic view of matters.

Marina Warner, another regular contributor to the London Review of Books penned an impassioned piece on the “disfiguring of higher education” following the enforced departure from her job at Essex University. Every single aspect of university existence appears to be going to pieces according to Warner and, moreover:

The new managerialist philistinism is spreading. Even as it claims to be keeping universities alive and well and inclusive, it is wrecking the ideal of emancipation through learning. If universities continue to go the way of the corporations, a fine system of public stewardship, evolved over the decades to educate citizens for their good and the good of society in the present and the future, will have been perverted and disfigured.

Bad news therefore.

Terry Eagleton, clearly showing which way he is leaning in The Slow Death of the University , sees pretty much everything going wrong in HE:

If the humanities in Britain are withering on the branch, it is largely because they are being driven by capitalist forces while being simultaneously starved of resources.

And then, of course, there is Sebastien Thrun who back in 2012 predicted that by 2050 there would only be 10 universities left in the world. It doesn’t get much more apocalyptic than that.

Universities – it’s not looking good

Doomed

Some of these books and articles refer to the UK, some to the US or more broadly to higher education across the globe, but they all share a common theme. We are all doomed.

Beyond the tsunami narrative which was all about how MOOCs were going to sweep away traditional universities in a tidal wave of disruption (which has not actually happened yet), the general view seems to be that higher education is in crisis one way or another. Indeed, you could be forgiven for detecting a note of frustration in some of these pieces about the seeming reluctance of universities to roll over and die.

In the more domestically focused pieces there is a clear and pervasive line about how government in England has ruined our higher education institutions and how university managers have been complicit in the catastrophe. Not only are universities generally approaching the end of times but the humanities are already in life support apparently, essentially due to the market approach of current and previous governments and the short-sighted philistinism of university leaders.

In the more domestically focused pieces there is a clear and pervasive line about how government in England has ruined our higher education institutions and how university managers have been complicit in the catastrophe. Not only are universities generally approaching the end of times but the humanities are already in life support apparently, essentially due to the market approach of current and previous governments and the short-sighted philistinism of university leaders.

This might be described as the Private Frazer approach to the future of higher education. Private Frazer was the perpetually gloomy and pessimistic funeral director and part-time Home Guard member in the 70s sitcom set in wartime Britain, ‘Dad’s Army’, and his world view can be summarised as “We’re doomed”.

(There is, interestingly, a line of argument in the US which is the mirror image of this in which the conservative right blames liberal America for brainwashing the nation’s youth at college and sending universities to hell in a hand basket. Still doomed.)

A long and painful death

All of these pieces, while expressing nostalgia for one kind of academic golden age or another, tend to deny, strenuously, that their arguments represent such yearning. Marina Warner’s piece is a particularly heartfelt one and she really wants universities to be very different to what she sees as their current construction. Rather than some kind of corporate beast which is what she sees universities have become Warner would prefer it if we could see them as being more of a social amenity like a public coastal path or an urban farm. All very touching but this is golden age nostalgia by the bucketful.

So are we all doomed as the general thrust of these pieces would suggest? Certainly it does seem that there is not a lot of interest in any optimistic prognosis about the future.

Treasury likes graduates, but not universities

Treasury has a view, long held, that universities are excessively well-funded and extremely inefficient. In times of continuing austerity, where difficult funding decisions have to be made and priorities chosen, then it is likely that universities will be facing cuts in public funding. Especially when universities have been described as being ‘awash with cash’ and not affected by wider spending cuts. Jeremy Clayton, director of knowledge and innovation strategy and international at the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, as reported in THE, recently said:

that higher education had also been criticised for having too many excessively paid employees and was seen as a sector ripe for cuts despite having achieved efficiency savings worth £1 billion over the past three years.

“I have heard politicians from across the political spectrum say that universities are feather-bedded, worse than bankers and just not living in the real world,” Mr Clayton told a Universities UK event on efficiency on 25 March.

We have been largely protected from the cuts of the last five years but this is extremely unlikely to continue under the new government. No matter how powerful our case is about the efficiencies made to date (such as in the recent UUK Diamond report) and the enormous economic and social benefits to the country of an outstanding higher education system, we are going to face cuts.

Sucking it up

So, will universities cope? Or are we all doomed? One of the most delightful examples of golden age nostalgia which appears regularly in presentations is the reminder that of the small number of institutions in the world which have existed continuously since the middle ages the vast majority are universities. There is something terribly touching and reassuring about this although it does always sound extraordinarily complacent.

However, it does seem to me there is actually something intrinsic to university operations, about the pace of change, the day to day rhythm of universities and the cycle of the academic year (itself based on mediaeval patterns) that is advantageous to long term sustainable existence. Universities do take time to change and tend on the whole not to act rashly and catastrophically. And of course part of universities’ core business of fundamental research is of itself long term in nature. Given this it is perhaps surprising that universities often seem to struggle to take a genuinely long term view: few if any have strategies which look beyond five years.

Nevertheless institutions should not be swayed by short term perturbations. And it seems to me to be irresponsible to describe current challenges in apocalyptic terms. This is not to say there are not long term challenges too. As many commentators have noted (and as the Labour Party’s fee reduction election pitch was partly based on), the long run cost of the current fees and loans scheme for undergraduates doesn’t look too bright for the public finances.

As the cuts come in higher education, as they surely will, universities will have to cope, to repriortise and adapt. One of the frequent complaints from all quarters is that there are many more administrators in universities than there used to be, they need to be cut back and, as they are just “back office” they are quite dispensable. However. there are many, many more regulations to which universities are subject and many more student services which are provided and staff and students in universities do need to be supported. I’ve written before here about the need to recognize professional services staff properly but all of these areas will inevitably come in for renewed challenge as the cuts bite.

There may be trouble ahead

There are undoubtedly tough times ahead. But are we doomed? No. Universities have to look to the long term and have to continue to invest. If we accept the most negative of these prospectuses we would all just give up now. But they aren’t true and we can’t let them be so. Our universities are not collapsing. The Humanities are not dying. There is and will continue to be huge demand for higher education in this country and across the globe.

It is of course much easier to call crisis, to identify failings and to attack, cry betrayal and criticise leaders. Sometimes this is justified. but when it becomes the dominant narrative then we are really not doing ourselves any favours in higher education.

Some will remember scale of cuts back in early 1980s. Now that was bad. But universities survived. Individual, departmental, discipline, faculty, institutional success can’t be wholly built on the basis of continuous crisis. Not all platforms can be burning all the time. We have to have a narrative of optimism, whatever the challenges. And the doom-mongers seem to have used up all of the apocalyptic rhetoric already so there must be reasons to be cheerful.

To return then to Dad’s Army it really seems more sensible to listen not to Private Frazer but to Corporal Jones:

Don’t panic. At least not yet.