What do the 2005 Conservatives, 2010 Liberal Democrats, and 2017 Labour Party have in common? Each, in turn, promised to abolish university tuition fees.

It appears that a promise to abolish fees is now a required manifesto promise for any major political party going into a UK election that they do not expect to win. Indeed, the ubiquity of such promises, along with the Liberal Democrats’ failure to keep theirs upon going into government in 2010, has given abolishing tuition fees a reputation for being an undeliverable policy. Scotland is, of course, another matter, though following through on the pledge for free tuition has arguably caused the SNP their own share of problems when it comes to making university access more equitable.

The high costs

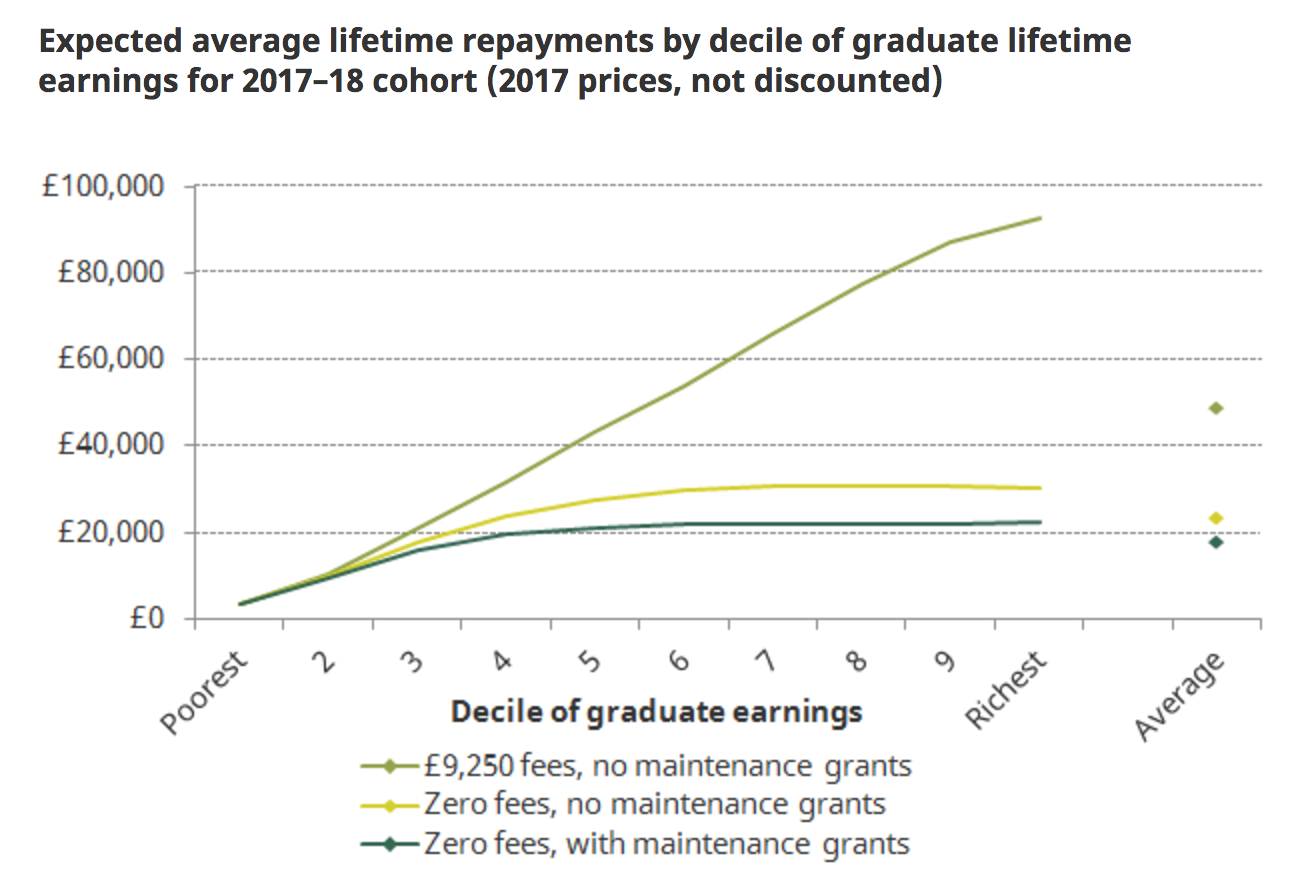

As Gavan Conlon has set out, the policy is – in pure isolation – regressive. Abolishing fees will primarily benefit higher earning graduates who are due to pay back their student loans plus interest. Conlon’s model suggests that to replace the lost tuition fee income and restore maintenance grants as promised, the state would need to find over £9 billion per cohort of students. The IFS and others have produced similar costings that demonstrate this, as well as how very little will change for the lowest earning graduates.

Source: IFS

Labour themselves price the policy at £11.2 billion, by far the largest single pledge amongst their manifesto spending promises, and overshadowing other spending commitments on early years, schools, and technical education. In launching the party’s plans for a wider National Education Service, Shadow Education Secretary Angela Rayner had hoped to ensure greater attention was given to these other areas.

This imbalance is somewhat typical of tension at the heart of Labour right now. The costs of abolishing fees are high, and there are clearly other areas of education and the public sector that some leading party figures would prefer to be prioritised. But the abolition of tuition fees is an article of faith for the left of the party who have been solidly wedded to scrapping fees since Tony Blair’s government first introduced them.

Post-truth policy?

Perhaps what is most striking, and most frustrating, about the state of the fees debate is how so few arguments appear to be based on evidence. The claim in the manifesto that “last year saw the steepest fall in university applications for thirty years” is just plain wrong. The fall in university applications applies to this year’s cycle, and 2012 (the year in which fees were trebled) saw a larger decrease in applications, which has since been more than made up for by growing demand more recently. This year’s fall appears to have less to do with £9,000 fees than it does with Brexit, the abolition of NHS bursaries, a decline in the eighteen-year-old population, and a continued decline in demand for part-time study.

There is only very limited evidence that debt aversion prevents access to full-time higher education, and the English sector has closed the entry gap between the most and least advantaged applicants since higher fees were introduced. This is primarily as a result of the subsequent uncapping of student numbers, and the restriction on student numbers in Scotland, a logical necessity of the Scottish Government’s policy of free tuition, which has prevented similar progress in closing the access gap there.

On the other hand…

Proponents of the current system have their own questions to answer. The abolition of maintenance grants and inflated costs of student living risk making some forms of higher education less affordable. And besides the question of affordability, tuition fees have perhaps had a more perverse impact when it comes to the marketisation of the sector. One can reasonably argue that the current funding system incentivises inefficient expenditure on marketing, risky capital investments in superficial infrastructure improvements, the drastic decline of part-time and adult study, and financial struggles for a small number of lower-tariff universities squeezed by competition and expansion elsewhere. The squeeze on international student recruitment, primarily concentrated at the lower-tariff end of the sector, has only exacerbated these challenges, as will Brexit. Both only raise the stakes of domestic market competition.

There are also more prosaic questions about the ethics of ‘buying and selling’ higher education, and whether this leads to productive behaviours on the part of students and teachers.

But none of these problems have so far been used by Labour to justify their policy, and it is unclear that simply abolishing fees would answer all of them. However, the sheer complexity of the current loan system – RAB charges, discount rates, repayment thresholds and all – has perhaps made an informed public debate on university funding almost impossible. Perhaps there just isn’t the space in pre-election manifestos to explore these issues in full. And opponents of Labour’s policy within the party will still ask whether even the above problems with the current system justify the massive £11.2 billion cost.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter. Despite recent improvement, Labour’s polling position is still looking bleak, just as it was with the 2005 Conservatives and 2010 Liberal Democrats. But hidden in the high-flying Conservatives’ manifesto is a promise for a “major review” of tertiary education funding, though for very different reasons to Labour’s interest in this area. Whatever the election result, the debate about the pros and cons of tuition fees is not going to go away.

For a longer analysis of the confusion caused by student debt, read David Morris’s commentary here.

Good analysis. The one other aspect I wonder about (and more research is needed in this area) is whether there is a link that could be proven between the cost of higher education and the staggering rise in reported cases of mental health issues on our campuses; I suspect a not-insignificant number of cases can be linked to worries about meeting day-to-day living costs and/or mental exhaustion from having to work longer hours alongside their studies to make ends meet. Also – how does the annual cost to the state of free-at-the-point-of-delivery compare to the costs inherent in a loans… Read more »

Other questions that need to be included within any analysis are the effect on the quality of education of the customer-service and finance-driven commoditisation of university education. Universities are increasingly being operated as centres of profit and loss while students are, inevitably, increasingly aware of receiving value for money. Neither necessarily equates with a system which allows for academic rigour, promoting standards of excellence and being prepared to countenance failure if it is deserved.

Agreed – we do note this in takling about the ethics of “buy and selling” higher education. I’ve always felt NUS’s analysis of this here is particularly prosaic: http://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/a-manifesto-for-partnership

This analysis doesn’t consider the costs of administering the loan system, nor the impact on students or on the economy after they end their studies with a debt of £27,250+.

[…] overshadowing other spending commitments on early years, schools, and technical education”, said Wonkhe.If the money was not spent on the fees-free policy, said Times Higher Education (THE), “it might […]

[…] At the time Labour, who had committed to abolishing tuition fees, calculated the bill at £11.2bn a year, “by far the largest single pledge amongst their manifesto spending promises, and overshadowing other spending commitments on early years, schools, and technical education”, said Wonkhe. […]

[…] At the time Labour, who had committed to abolishing tuition fees, calculated the bill at £11.2bn a year, “by far the largest single pledge amongst their manifesto spending promises, and overshadowing other spending commitments on early years, schools, and technical education”, said Wonkhe. […]