Edtech: what works? It’s a question which I’ve heard asked more often in the last year than at any point since the demise of schools technology agency Becta in 2010. The Department for Education’s new edtech team raised it as a cross-sector priority late last year; it turned up in the industrial strategy white paper; and Nesta has highlighted it a number of times, including a recent blog post. So it was great to be part of a panel at Wonkfest recently discussing this very topic.

This being 2017, and Wonkfest, data-informed insights featured heavily in the discussion of the technologies and approaches that panelists believed had the potential to make a difference for learners, teachers and universities.

In her contribution, Hazel Rymer of the Open University highlighted the fascinating work they’ve been doing on learning analytics, which is proving effective in helping their tutors to identify students at risk of underperforming or dropping out. Meanwhile, Ellen Morgan from Pearson cited another piece of the analytics jigsaw, the detailed data that can now be obtained on how students have engaged with learning materials, and how this can help lecturers tailor their teaching.

People work!

But we’ve all been working in this area too long to think that the answer to “what works?” lies solely, or even predominantly, with the technology. It was flagged by ALT’s Maren Deepwell early on, and returned to by all the panelists throughout, that it’s the people who make technologies effective, and their creativity drives innovation and generates new practice. Because of the importance of people in planning and using edtech, with their different drivers, goals and experiences, my first reaction to the question about what works in edtech would be “who’s asking?” It really depends on your role and perspective.

For example, you might want to know that a review of the research evidence across educational sectors shows that most learning technology interventions are at least as good as the alternative traditional practice, and may confer other advantages for teachers and students. But it might be more important for you to understand how the students at your university feel about the use of technology on their course, or what they feels really helps them. Perhaps you want to know what to expect the impact of a roll-out of electronic marking and feedback to be on staff workload. Or, dare I say it, what your competitor institutions are doing?

Jisc’s student digital experience tracker survey provides one part of this jigsaw of evidence, offering universities and colleges insights into how their students are experiencing the use of digital technology as part of their learning experience.

The findings have given us a snapshot of the national picture. Generally, we see that students value the flexibility that technology can offer them, enabling them to fit learning more easily into their life and access resources from anywhere and on a range of devices.

Whither the VLE?

As you would expect, there are very high reported levels of use of virtual learning environments (VLEs) and online information, but the proportion of students reporting frequently doing the kinds of activities which make the most of digital technology to promote active engagement in learning drops quite sharply. So while nearly 96% frequently – that’s weekly or more – find information online, only 35% frequently work online with others. Around half have never used a game or simulation for learning or used polling or online quizzes in class.

Since almost all universities have the technologies to enable these things, this brings us back to “what works?” being about people just as much as it is about technology. Yes, there are considerations around reliability, accessibility and ease of use. But beyond that, many long years in working in technology-enhanced learning in higher education have taught me that most of the factors determining the success of learning technology implementations are down to people – culture, change management, communication, staff skills and buy-in.

Staff use of digital technologies in their teaching is strongly influenced by their own digital capability and confidence, as well as their beliefs about and experiences of teaching. As well as specific initiatives to increase digital capability, they tend to be influenced by examples of technology use within or transferable to their own discipline, and by the needs and views of their own students.

Students on group work

At the ALT conference this year, the University of Northampton showed a great example of how evidence from a variety of sources, including its own students, can be pulled together around active blended (“flipped”) learning, and turned into actionable guidance for their staff. One important area covered by the Northampton guidance – and a key part of the approach – is how best to facilitate online collaboration and group work.

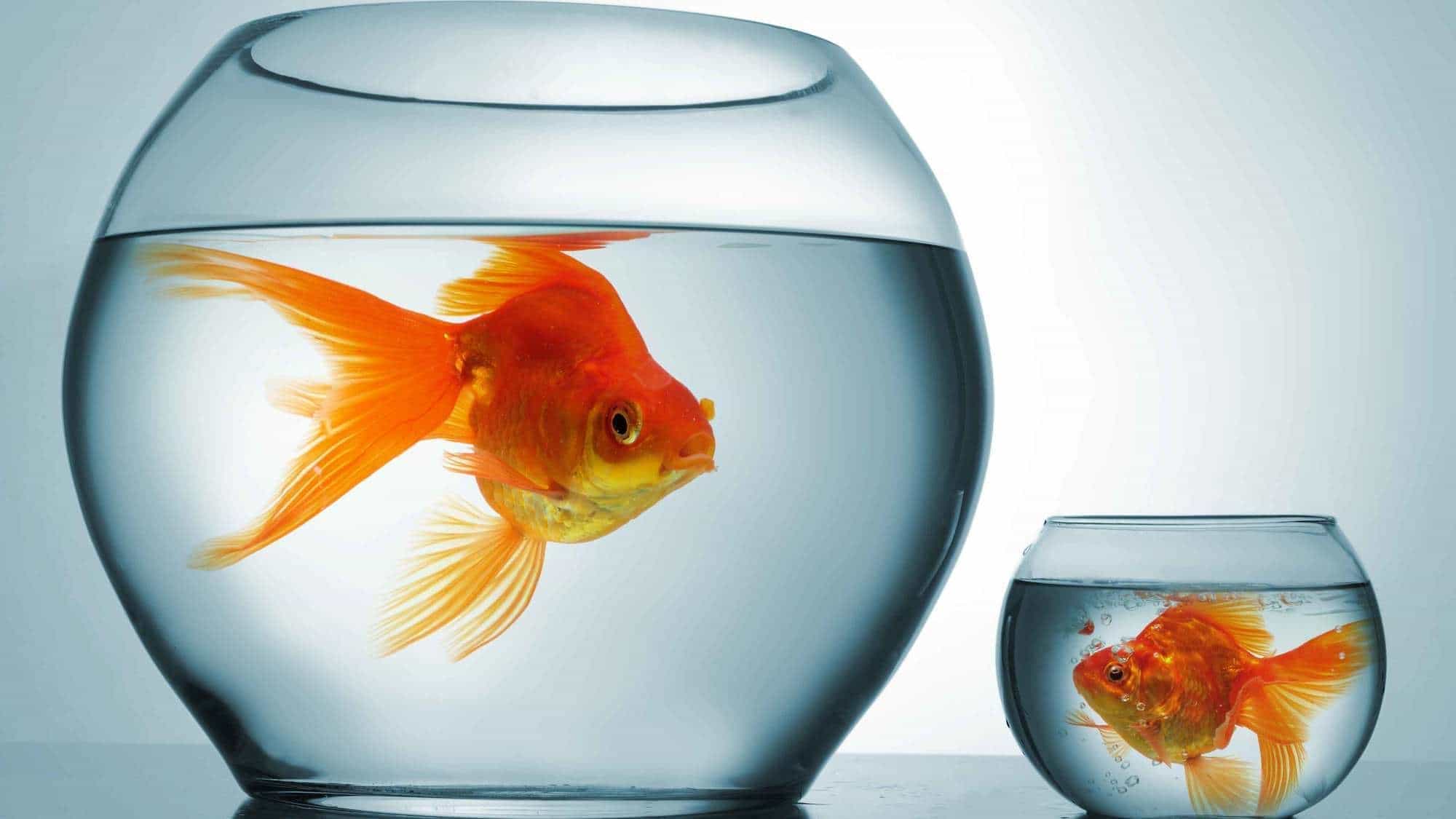

The national student tracker responses were mixed on group work. Formal and informal online collaboration and group work were often cited by students in their free text responses as a learning activity they’d enjoyed, but some students retain a strong preference for individual work, or for group work to be predominantly face-to-face.

Collaboration is often something that content-heavy VLE implementations may not support well – only 41% of students agreed that they enjoyed using the collaborative features of their VLE, though we can’t be sure what proportion of the remainder have had a chance to explore these. It will be interesting to see whether the new lightweight learning systems such as Aula, which put all the focus on engagement and interaction rather than course content, make a difference to how comfortable teachers and learners are in this space. The challenge for institutional technology provision will be whether tools like this – or like the wide range of lightweight or general consumer tools and technologies, which staff and students are using in various ways to support their learning and teaching aims – end up being used alongside, or instead of, a more traditional VLE.

The thought of moving away from your current VLE highlights one of the tensions at the heart of learning technology in educational institutions – how to balance enabling innovation and early adopters with maintenance and support of the business critical systems serving the majority of staff and students. Add into that the challenges of universities, with their often byzantine decision-making and procurement processes, working with new edtech companies which often need to move fast to keep themselves going, and you can see how sometimes implementations can get stuck in perennial pilot mode rather than really harnessing new ideas to drive change across the board.

Analytics and evidence

Like my fellow panelists, I’m interested in the potential of learning technologies and analytics to contribute to data-informed improvements in learning and teaching. There is increasing evidence of the impact of learning analytics on retention and student achievement, including new findings from the OU indicating that the extent to which a tutor accesses the learning analytics dashboard on their tutees is the second biggest factor in predicting whether students will pass their module after their prior attainment. We’re currently exploring how to make best use of learning analytics to support student wellbeing. Beyond this, it can help to throw a light on how students’ digital study behaviour is affected by how their courses are designed and delivered, and how this impacts on their learning.

That, for me, is the really fascinating outcome. It’s useful to course teams, enabling them to flex their approach to maximise engagement, but also offers a rich new seam of research data and the promise of another type of answer to the “what works?” question.

“a review of the research evidence across educational sectors shows that most learning technology interventions are at least as good as the alternative traditional practice”.

If the goal is to find “improvements in teaching and learning” it seems from this that edtech doesn’t ‘work’. Is that right?

No – there is large-scale evidence that the effective use of technology and the teaching innovations this enables do improve teaching and learning. Studies by the National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT) in the USA over a 15-year period show that systematic institutional-wide approaches to course design can lead to better outcomes and retention. A meta-analysis of 156 NCAT projects found that 72 per cent of the projects demonstrated an improvement in learning outcomes, while outcomes in the other 28 per cent remained broadly the same as before the course redesign. The evaluation also noted increased completion rates and ‘increased… Read more »