Since President Trump rolled out executive orders to eliminate DEI programmes and began to unpick the funding infrastructure of American research, a number of countries have offered safe haven to academics currently working in the USA.

As rector of Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Jan Danckaert, noted:

American universities and their researchers are the biggest victims of this political and ideological interference. They’re seeing millions in research funding disappear for ideological reasons.

From Singapore and Australia to Norway and Belgium, governments and individual universities around the globe are seizing the opportunity to attract the top American minds. For scholars fearful of their government’s policy direction on academic freedom, such as those working in gender studies, on vaccine research or climate change, the situation is urgent.

At risk academics

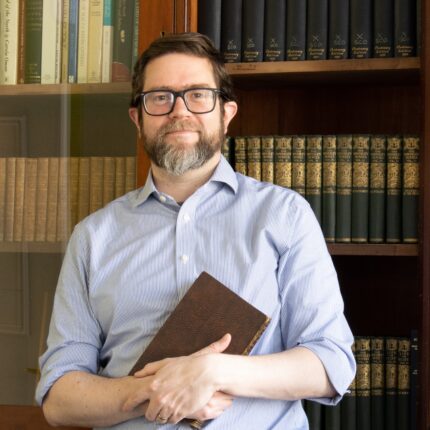

Yet this is nothing new. The Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA) has helped researchers escape persecution and conflict for almost a century, bringing the likes of Nikolaus Pevsner, Max Born and Albie Sachs to safety in Britain. Conceived in response to the Nazi assault on universities, CARA drove Britain’s scholarly rescue mission in the 1930s. At the same time, a parallel movement began in the USA. The Institute for Advanced Study was created at Princeton, with Albert Einstein appointed as the first Fellow in 1932. Other European academics such as Paul Dirac and Emmy Noether soon followed.

Just as German scientists sought academic freedom in the USA and UK in the 1930s, now American scholars are beginning to cross the Atlantic in the other direction. In France, Aix-Marseille University received around 300 applications for its Safe Place for Science initiative, which aims to offer 15 million Euro to support research across the next three years. The first eight researchers arrived in France in June, with up to 20 expected by the beginning of the new academic year.

The UK’s universities meanwhile seem mired in a funding crisis due to financial models all too dependent on precarious markets of international students, leading to shrinking budgets, staff layoffs and even the looming possibility of full-blown bankruptcy. Offering cash and “academic asylum” to any foreign academics in these straitened circumstances is unlikely to be seen as a priority. And yet Institutes for Advanced Study, or IASs, already provide the necessary infrastructure and perhaps the fastest means of response.

What is an Institute for Advanced Study?

Princeton’s Institute remains remarkable: since its inception, visitors have been selected solely on the basis of academic ability, regardless of gender, race or religion; its mission of Advanced Study centres the “curiosity-driven pursuit of knowledge” as a good in itself, with no view to practical application or the expectation of meeting predetermined goals. This approach, and the inherent interdisciplinarity of bringing together researchers across the sciences, arts and humanities, inspired counterparts around the world, including the UK’s first IAS at the University of Edinburgh in 1969. Other UK universities with an IAS now include Warwick, Loughborough, Durham, Stirling, UCL and Birmingham.

These Institutes vary in size and scope but all share Princeton’s founding mission of untrammelled academic freedom for blue-sky thinking. Interdisciplinarity is the scholarly keystone of Advanced Study. Researchers from diverse disciplines and career stages form a community of practice, which may also encompass artists, journalists, community activists and others who likewise benefit from a reflective, supportive, non-hierarchical environment in which to work. Conversations and serendipitous encounters in such an environment can be the “source from which undreamed-of utility is derived” in the words of Abraham Flexner, founder of Princeton’s IAS.

What can these institutes offer?

Amid difficult economic times, approaches to knowledge production have become ever more instrumental, with research increasingly valorised for its capacity to be commercialised or to have some form of impact beyond the academy. However, an overemphasis on applied research risks circumscribing the conceptual imagination that underscores so many scientific advances. The curiosity-driven IAS approach can be a necessary corrective to instrumentalism, bolstering a healthy research culture.

From their inception in the 1930s, IASs have also always had a moral mission to support colleagues around the world when threatened by conflict, displacement or, in the case of the new wave of populist governments, by illiberalism. For those escaping war and trauma, such institutes form quiet places of refuge, rehabilitation and recovery. A small institute can be agile enough to respond to urgent need when research is threatened, where a whole department is less able to pivot. It is worth noting that recent programmes for Ukrainian scholars and their families have tended to emerge from IASs, along with bespoke schemes for researchers from Palestine, Syria, Hungary or Türkiye – and now perhaps America.

Lastly, opportunities for career advancement have reduced across the whole university sector, nationally and internationally. Early-career scholars in particular face an impossibly precarious work environment, and staff development programmes are often the first casualty of cuts to expenditure. Whilst contracted research – as PDRA on a senior scholar’s project – can be an important stepping stone in the early stages of an academic career, there is a need for more funded opportunities to support independent research at postdoctoral level. IASs are one of very few means by which such research can flourish. Each year, hundreds of global scholars are appointed to IAS Fellowships at postdoctoral and more senior levels.

Given the polycrises facing the sector, turning us inward, perhaps it is necessary to reconsider higher education as a global commons. In doing so, universities must embrace their particular responsibilities as places of sanctuary, of fundamental knowledge production and as incubators for the next generation of scholarship. The concept of Advanced Study was created to foster innovation across all these areas in a time of persecution.

Now more than ever, Institutes devoted to that transformative potential could be the vehicle for promoting the highest standards of international collaboration, extending a hand to academics at risk in the global south and north, including our American counterparts.