Why do students run out of money? And is it their mistake?

It’s partly because student maintenance support has not kept pace with the cost of living.

Last year, the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University calculated that students need £18,632 a year outside London (and £21,774 a year in London) to have a minimum acceptable standard of living.

But if you’re living away from home in England, the maximum maintenance loan is £10,227 – and it’s less than that once your parents earn over £25,000.

And if you’re an international student, the Home Office’s “proof of funds” figure – the money you need to show you have in the bank to cover your living costs – has been (un)helpfully aligned to that inadequate figure.

In that scenario, you’d need help with budgeting – especially if you’ve never lived away from home before, if you’ve not participated in higher education before, or if you’ve never lived in the UK before.

You’d want to know, for example, how much a TV license costs. The good news is that your chosen university has a guide to student living costs, and it lists the license as costing £159 per year.

The problem? £159 was the 2021 rate – a TV licence now costs £174.50. Still, one little mistake like that isn’t going to break the bank, surely?

Delay repay

Over the past few years I’ve whiled away some of my train delays surfing around university websites looking at what the sector says about student cost of living.

I’ve found marketing boasts dressed up as money advice, sample student budgets that feature decades old estimates, and reassuringly precise figures that turn out to be thumbs in the air from the ambassadors in the office.

Often, I find webpages that say things like this:

The problem is that the “fact” turns out to be from 2023, the source on the “lowest rents” claim turns out to be “not yet reliable”, and the “one of the cheapest pints in the country” claim has its source this story in the Independent. From 2019.

That’s also a webpage that says you can get a bus to the seaside and back for £4.30 (it’s currently £12), a ferry to Bruges for £50 (the route was withdrawn in 2020), and a train to London for “for just over a tenner” – when even with a railcard, the lowest fare you’ll find is £22.66.

Campus gym prices are listed as less than £20 a month (it’s actually from £22.95 for students), rent for a one-bed city flat is listed as £572 (the source actually says £623.57), and you’re even told that you can head to a “legendary” local nightclub to “down a double” for £1.90.

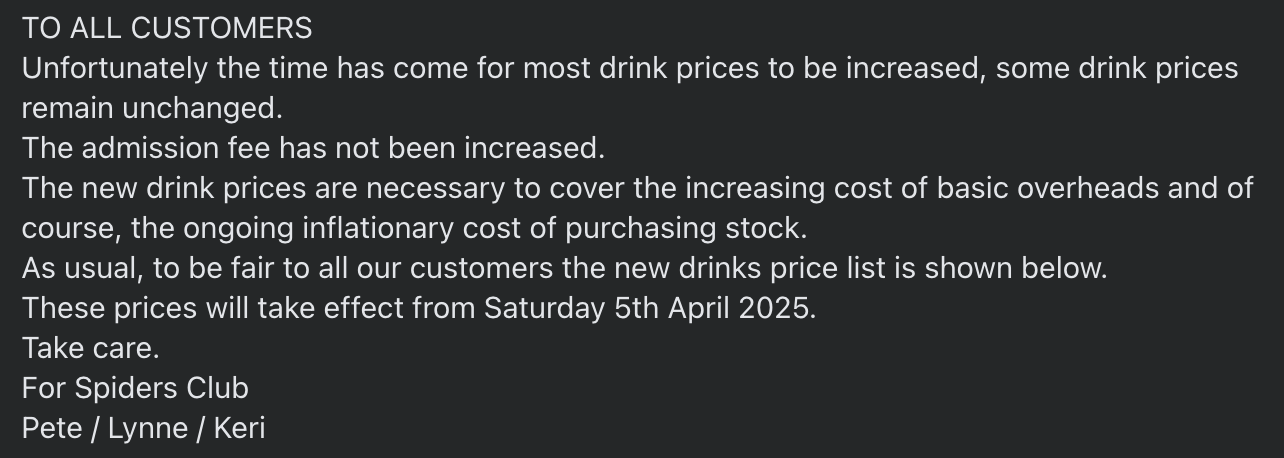

Sadly, even Spiders Nightclub is having to cover “the increasing cost of basic overheads” and “the ongoing inflationary cost of purchasing stock”. The current price is £2.50.

Those were the days

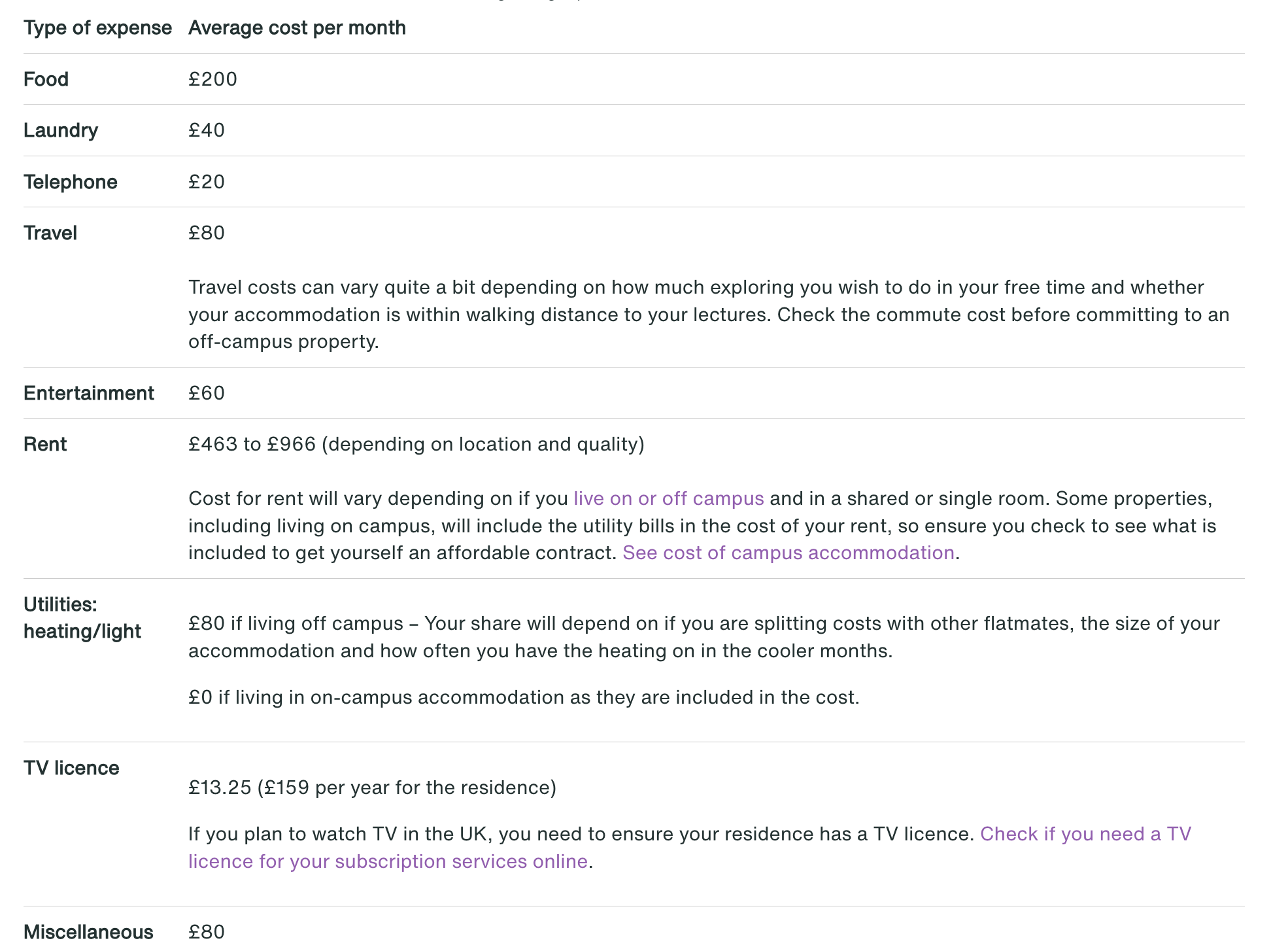

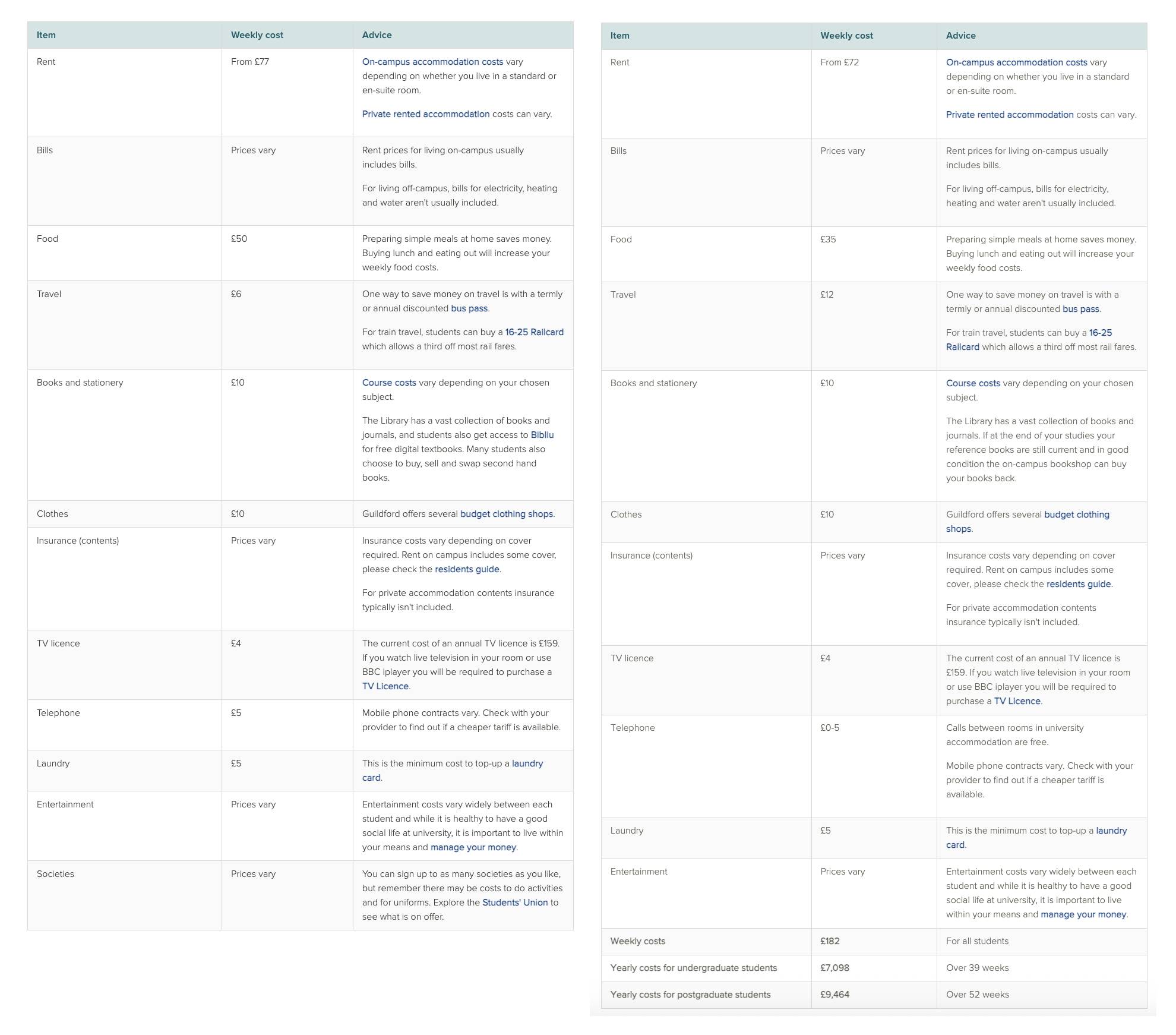

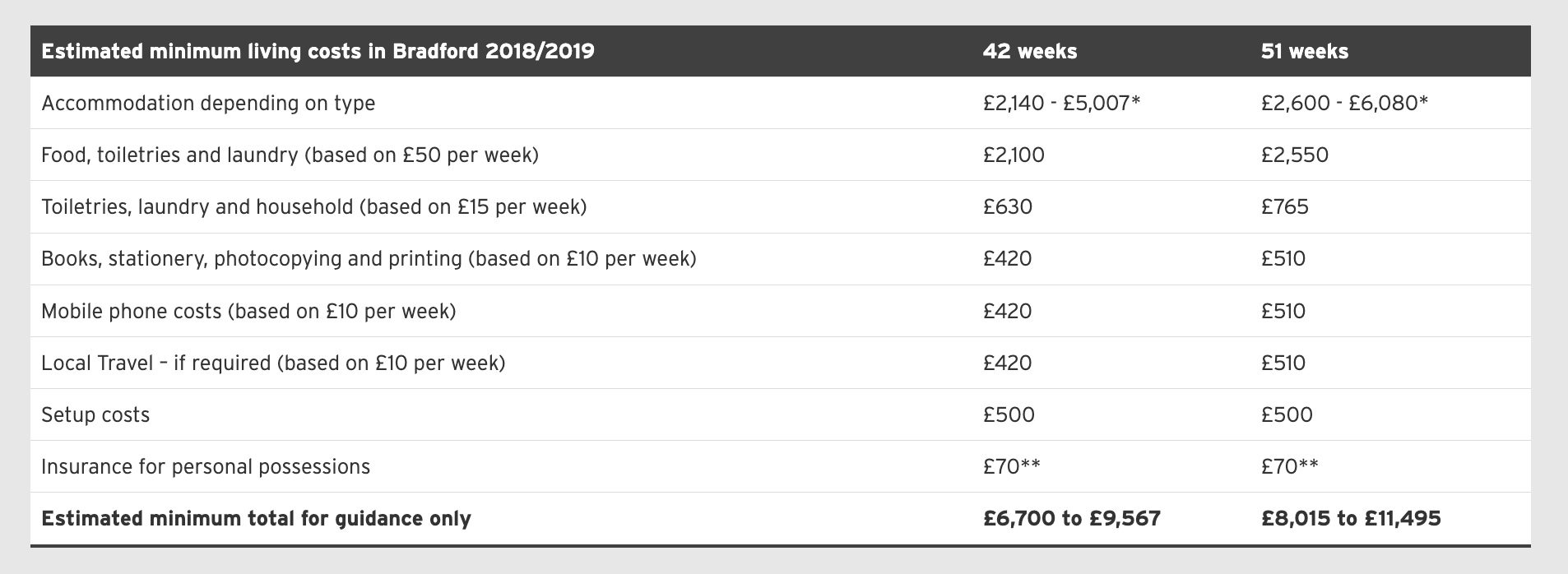

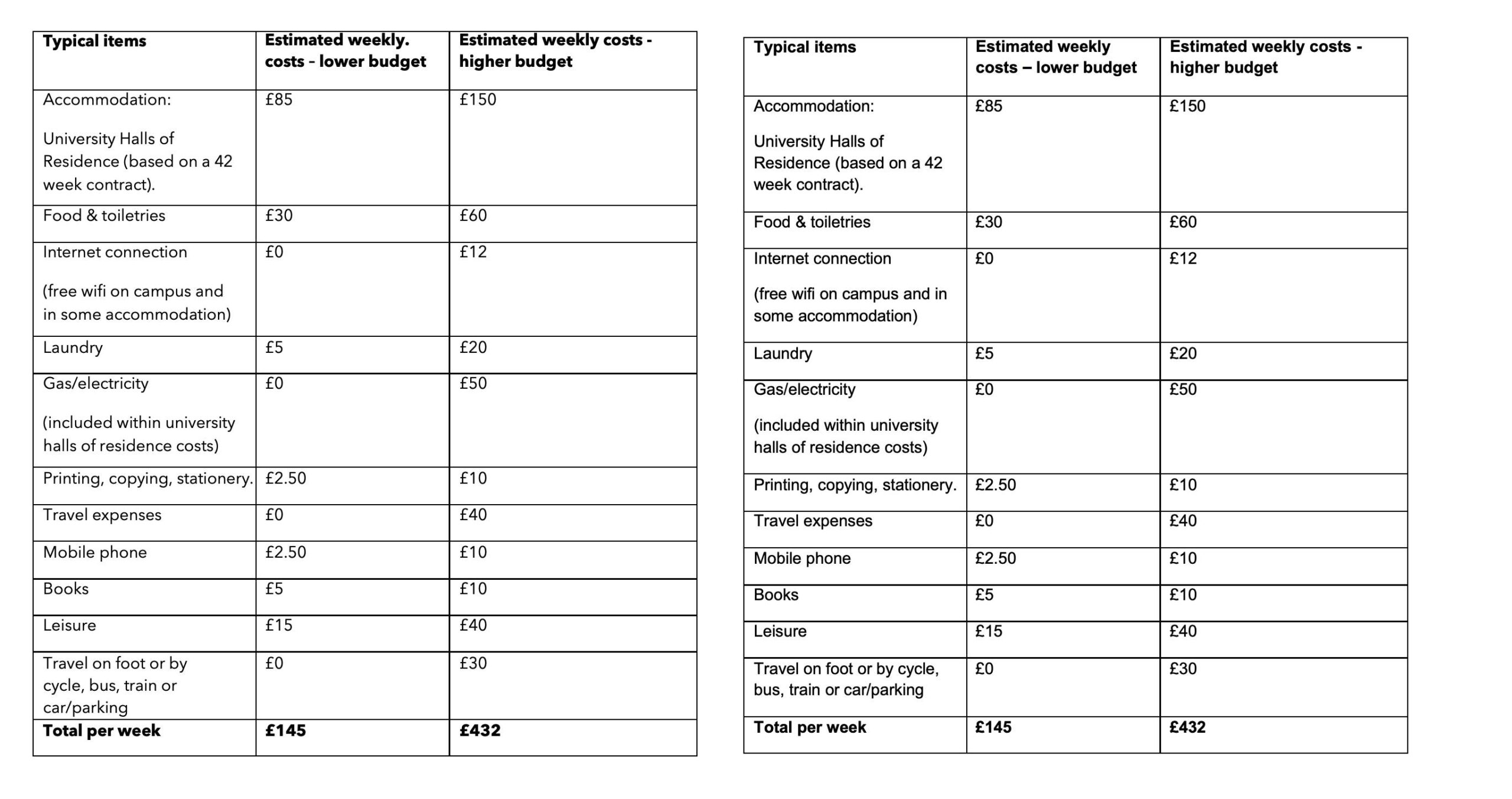

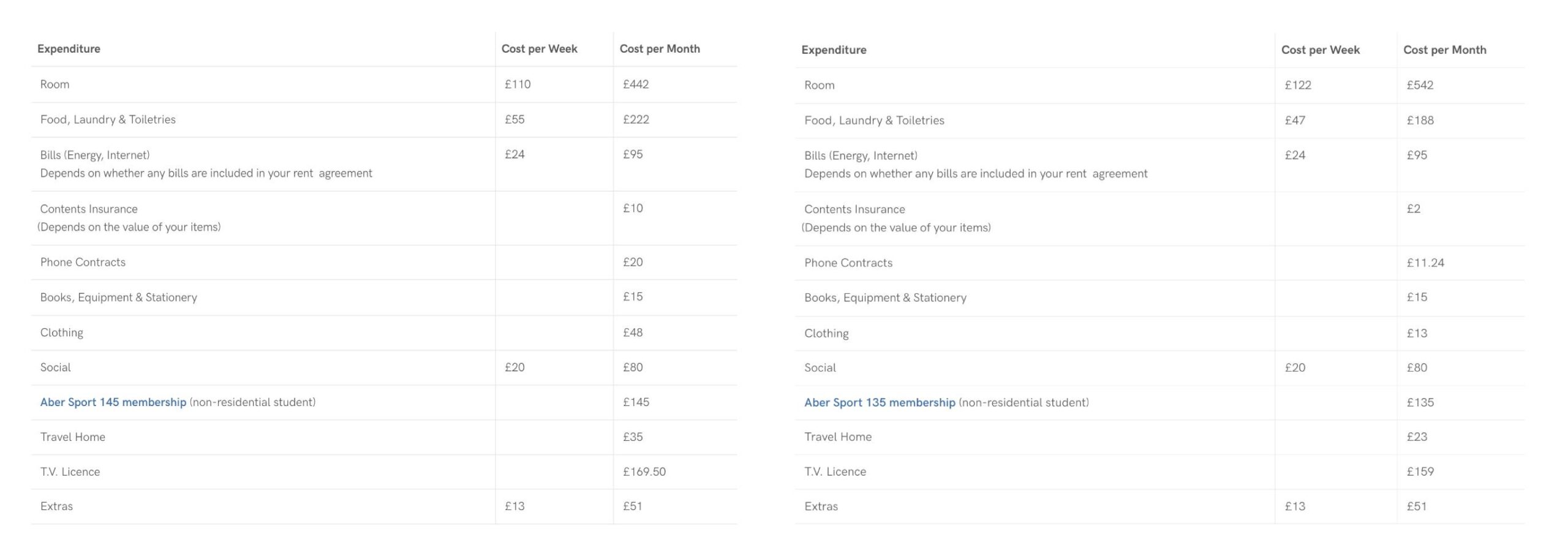

Sometimes, I find tables like this – where the costs listed appear to be exactly the same as when the webpage was updated in 2022.

Actually, that’s not quite true. Someone has bothered to update the lower rent estimate up to £500 a month since then – leaving all of the other figures unchanged.

Archive.org allows me to see all sorts of moments when someone, somewhere, has performed an update. Of sorts. Here’s one that urges readers to make a realistic spending plan at the beginning of each year:

Sadly, it looks like the “typical student budget” it offers students as guidance was more “typical” back in 2023:

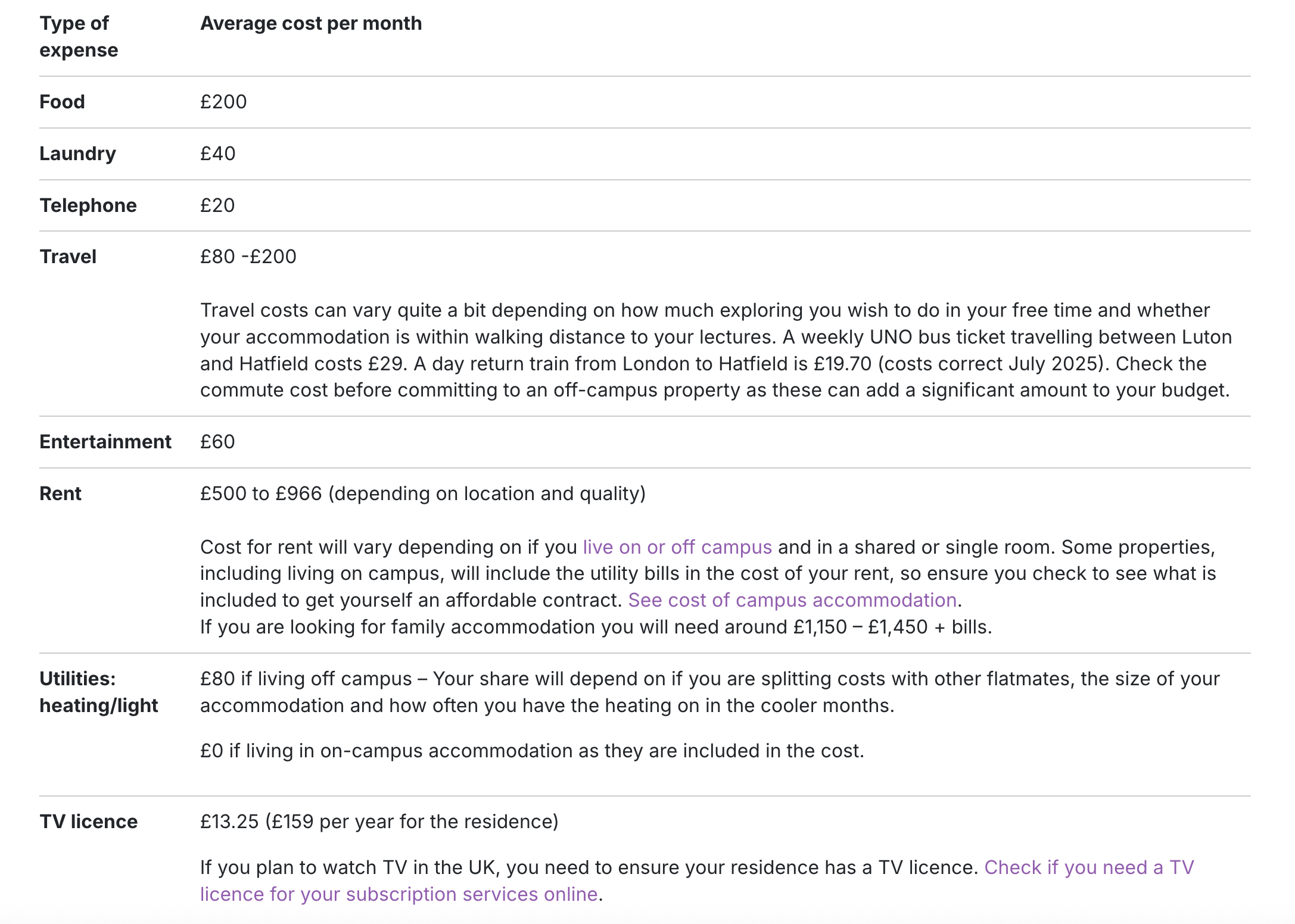

Here’s one where food and rent have gone up, but everything else is as it was in 2022. The main difference is that the “Yearly costs for students” lines in the table have been deleted – presumably because they would stretch credibility.

Here’s one which says that in comparison to some countries, the UK appears to be an expensive place to live – but with sensible planning and budgeting, students should find it affordable to live and study here. Until they get used to the cost of living here in the UK, they will need to plan and keep to a budget. A budget that the university hasn’t updated since 2022:

Which budget?

Not every university has a run at listing costs. Many (over 30 at the time of typing) refer their readers to the Which? Student Budget Calculator.

The Which? Student budget calculator was deleted in 2022 – and even when it was live, its underpinning figures were last updated in 2019.

Sometimes the google search takes you to undated slide decks and PDFs. This metadata suggests that this one is from 2023 – although the figures in it look suspiciously similar to the numbers in the UG prospectus in 2015.

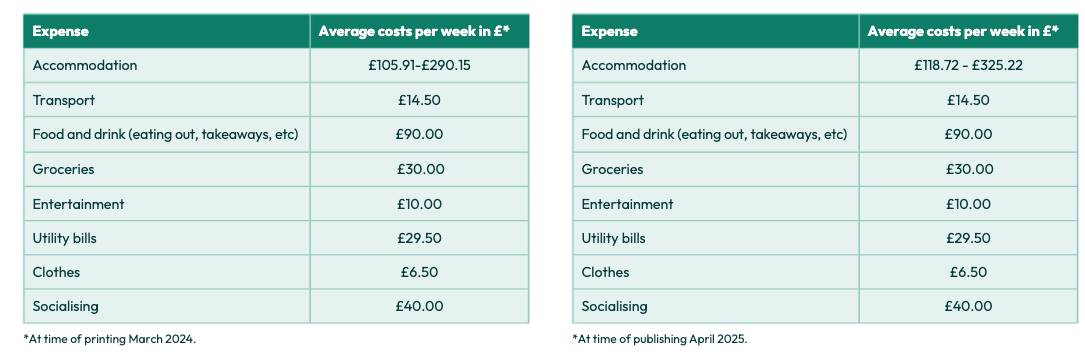

To be fair, that’s a university that has at least got an updated chart showing sample costs in its international arrival guide – with a reassuring note that average costs are correct as of March. You’d perhaps be less reassured to find that those average costs – other than the cost of (university) accommodation – have remained exactly as they were since last year.

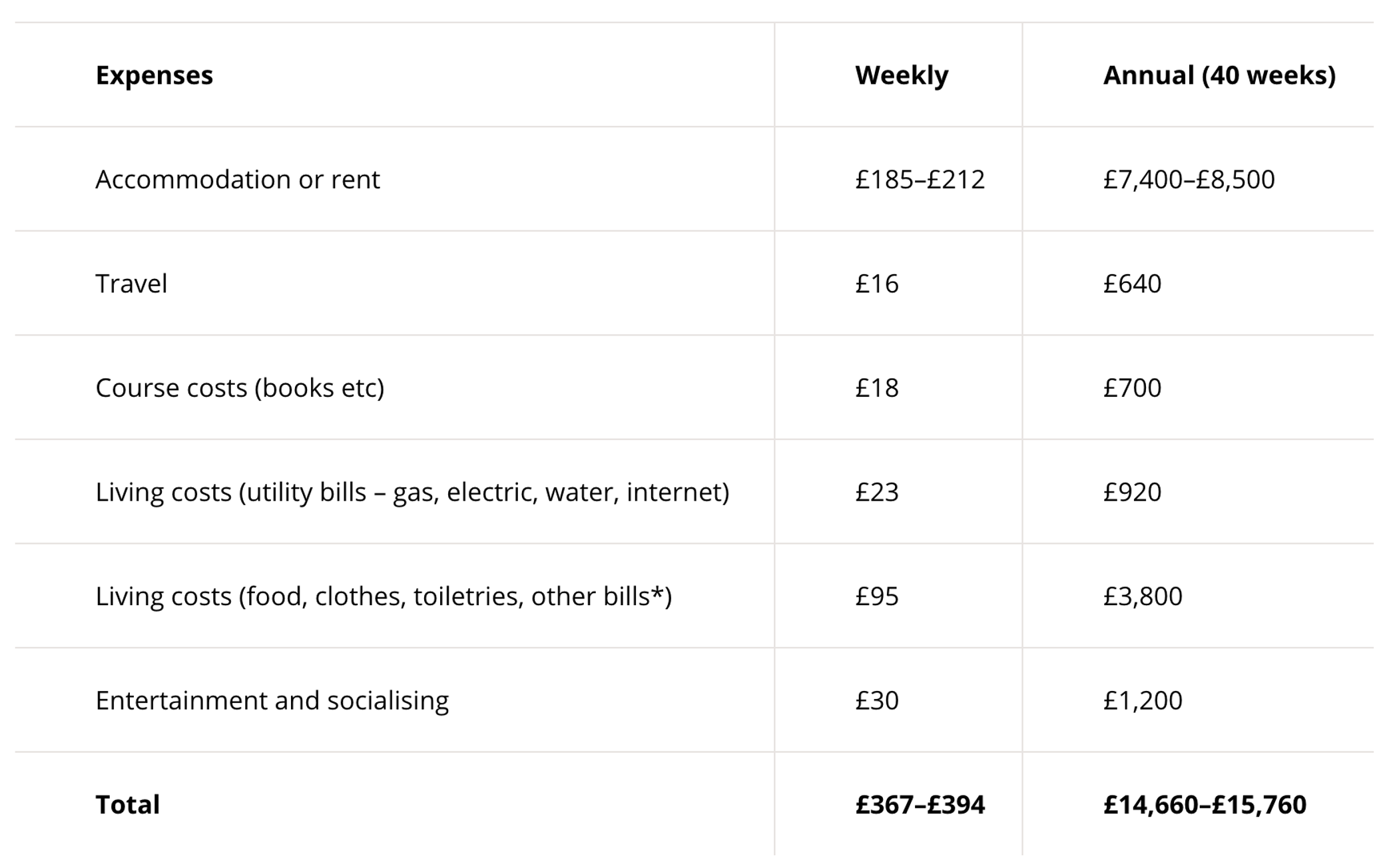

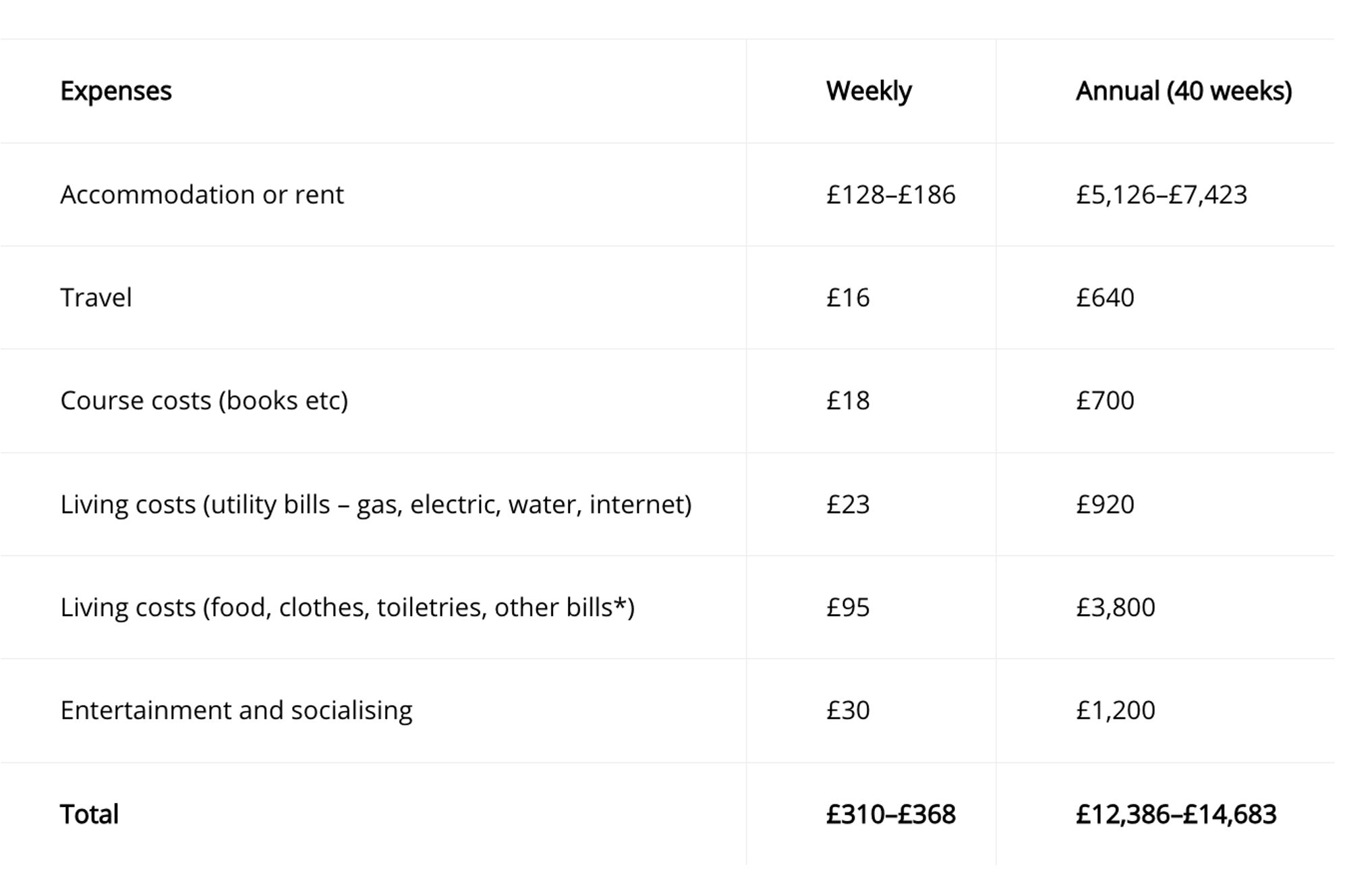

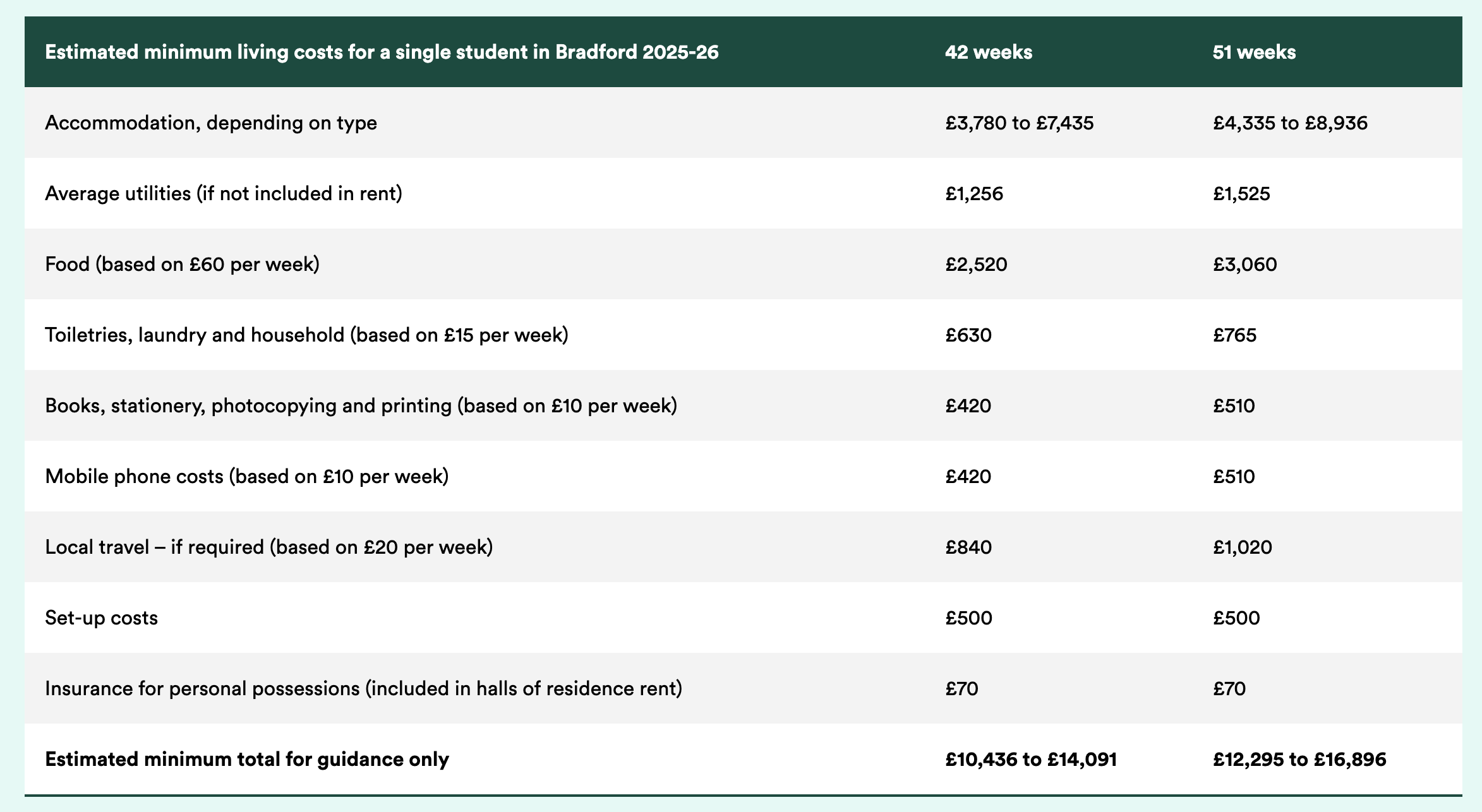

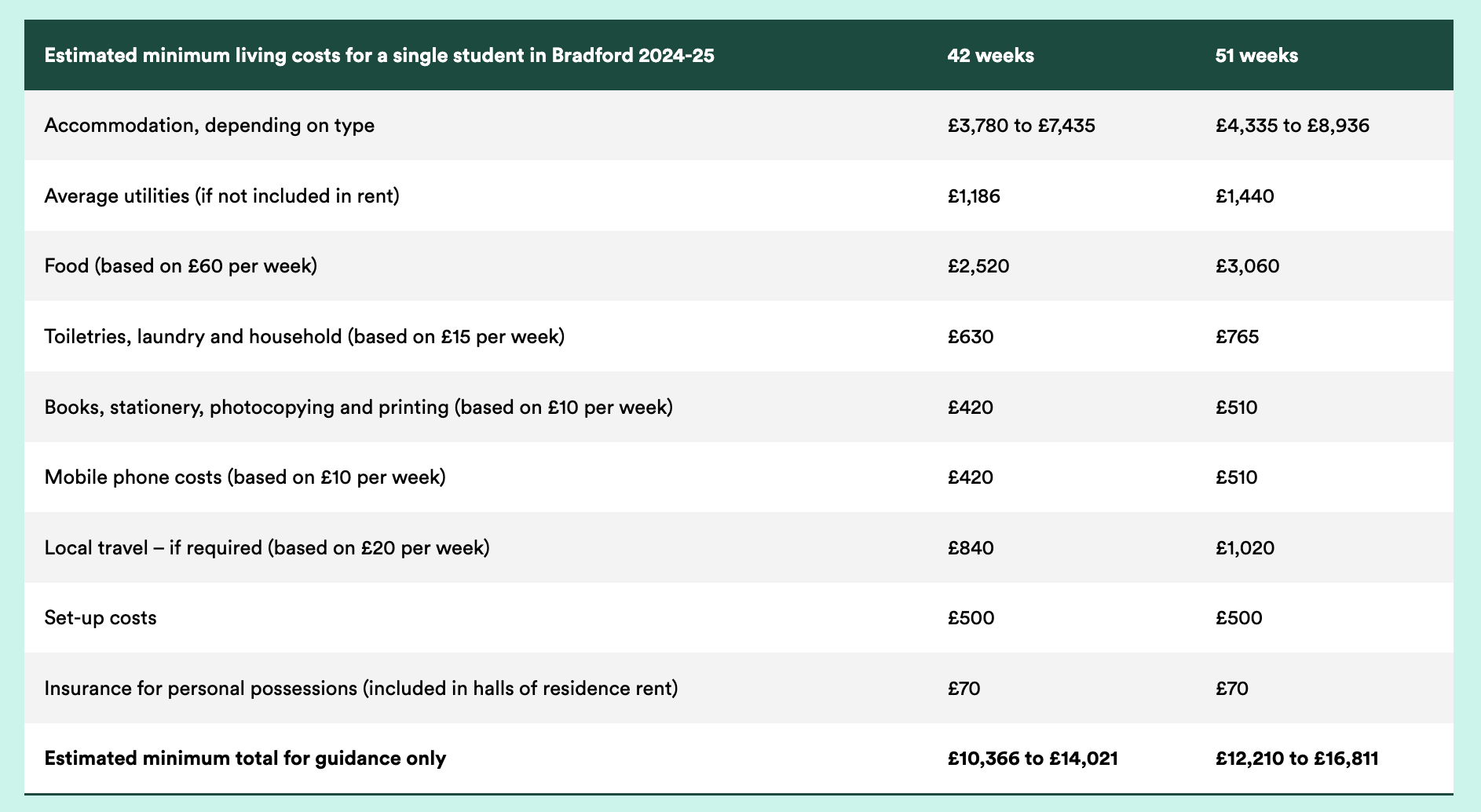

Sometimes, a picture is painted of painstaking research carried out by dedicated money advisors. Here’s a table that says the minimum costs have been estimated by the university’s support teams:

How lucky students in that city are, given that the only things that have increased over the past year are accommodation and rent:

Actually, tell a lie. Many of the costs seem to be identical to those in 2020:

Save us from your information

Lost of the sample budgets and costs are unsourced – but not all of them. A large number quote figures from Save the Student’s student money survey – which last year used responses from 1,010 university students in the UK to calculate the results.

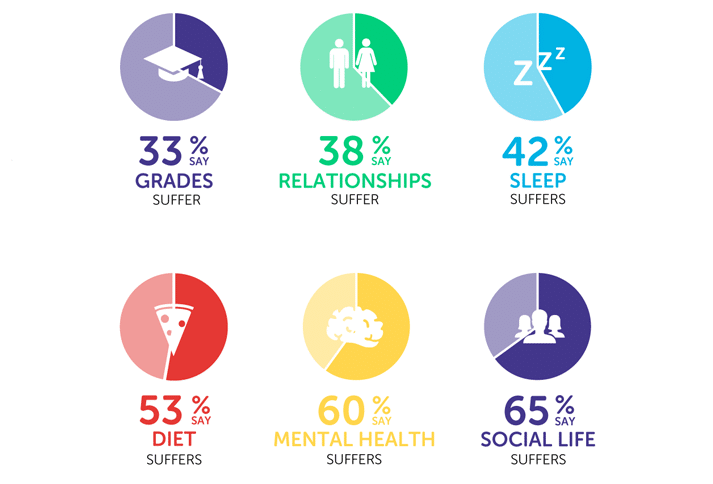

Even if that was a dataset that could be relied upon at provider or city level, that was a survey that found 67 per cent of students skipping meals to save money, 1 in 10 using food banks and 60 per cent with money related mental health problems. Not a great basis on which to budget, that.

Others quote their costs from the NatWest Student Living Index – which for reasons I’ve explained in 2024, 2023, 2022 and 2021, isn’t an approach that I think comes close to being morally sound.

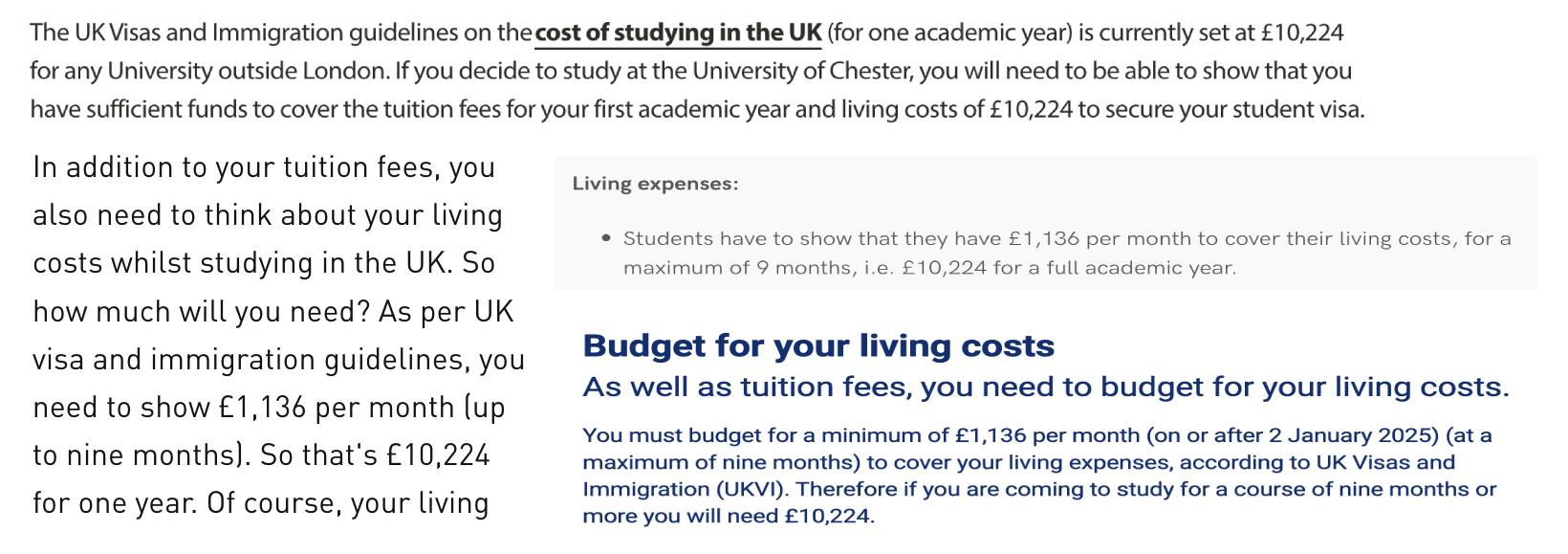

Plenty of universities don’t list costs at all, but imply to international students that the “proof of funds” figure has been calculated by Home Office officials as enough to live on:

It has, of course, just been copied across from DfE’s maximum maintenance loan – a figure widely believed to be wholly inadequate as an estimate of living costs for students.

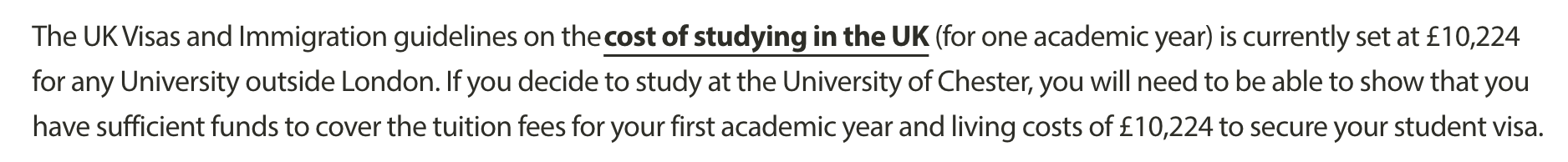

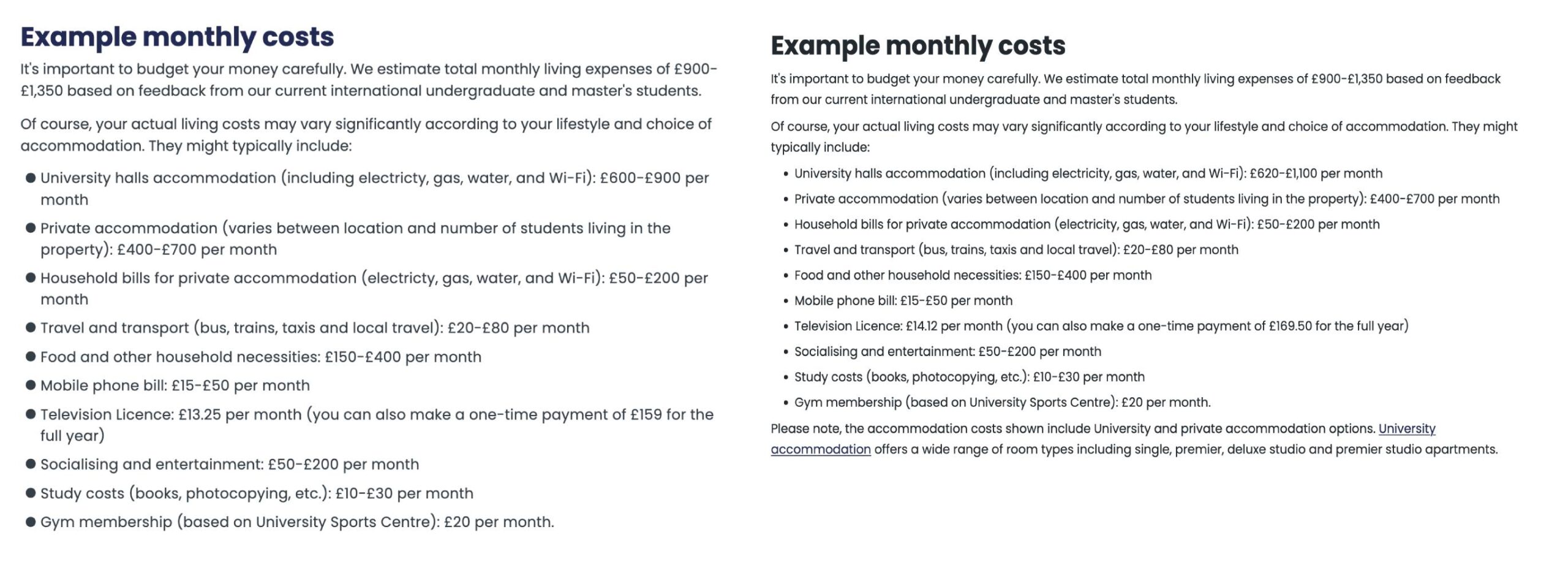

Sometimes you find things like this, a set of costs “based on feedback from our current international undergraduate and master’s students”. Someone has gone in and updated the costs for university halls – but hasn’t updated anything else, and nor have they updated the estimate for total monthly living expenses:

Sometimes you find things like this – costs that haven’t changed in two years contained in an official looking document called “Student Regulations and Policies: Standard Additional Costs”:

And sometimes you find miracles. Here’s a university where most of the costs haven’t increased in 18 months, and the cost of clothing has fallen dramatically – despite ONS calculating that clothing inflation is currently 5.9 per cent.

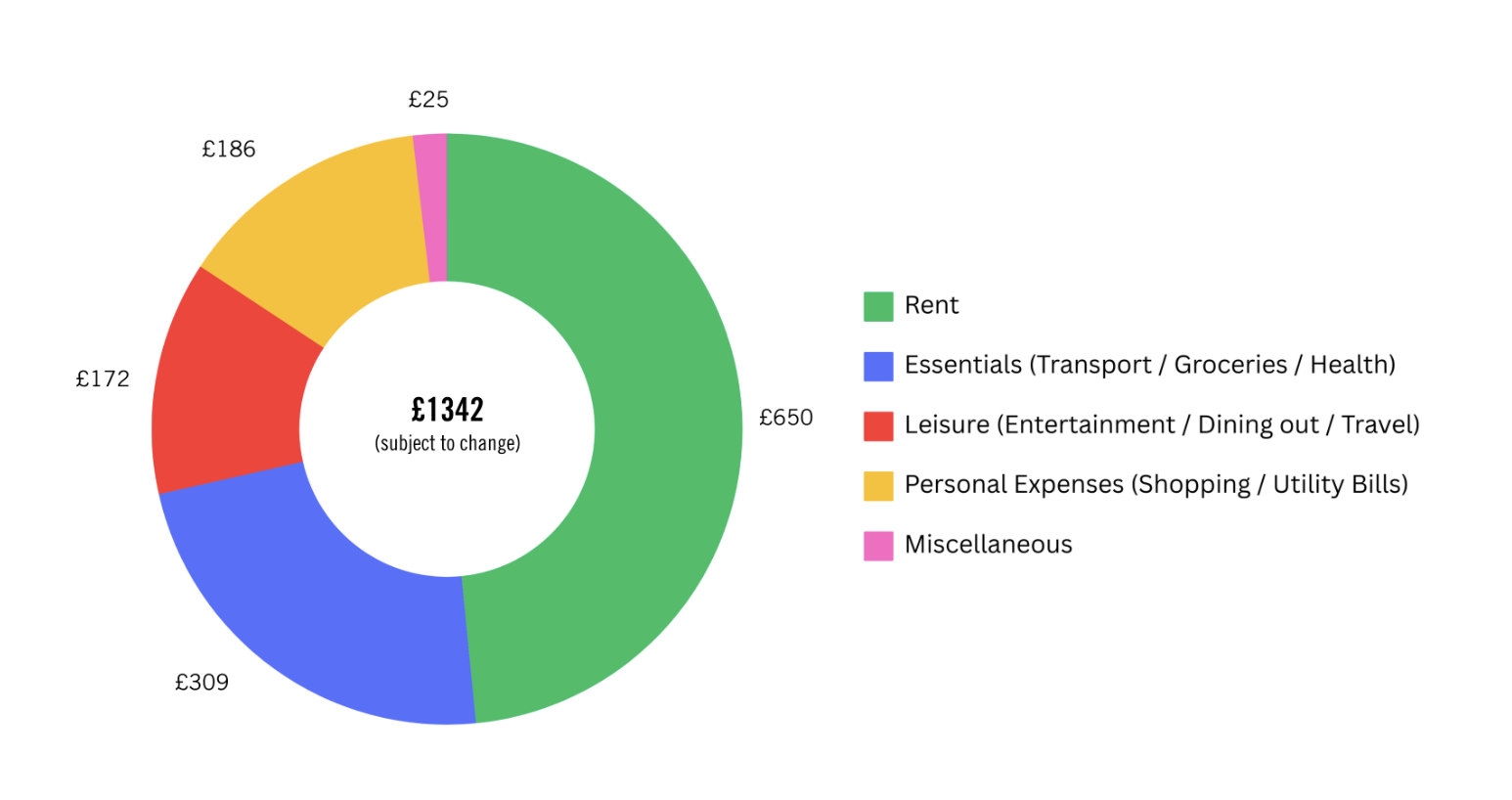

Then there’s charts like this that are “subject to change” – although no change since last summer:

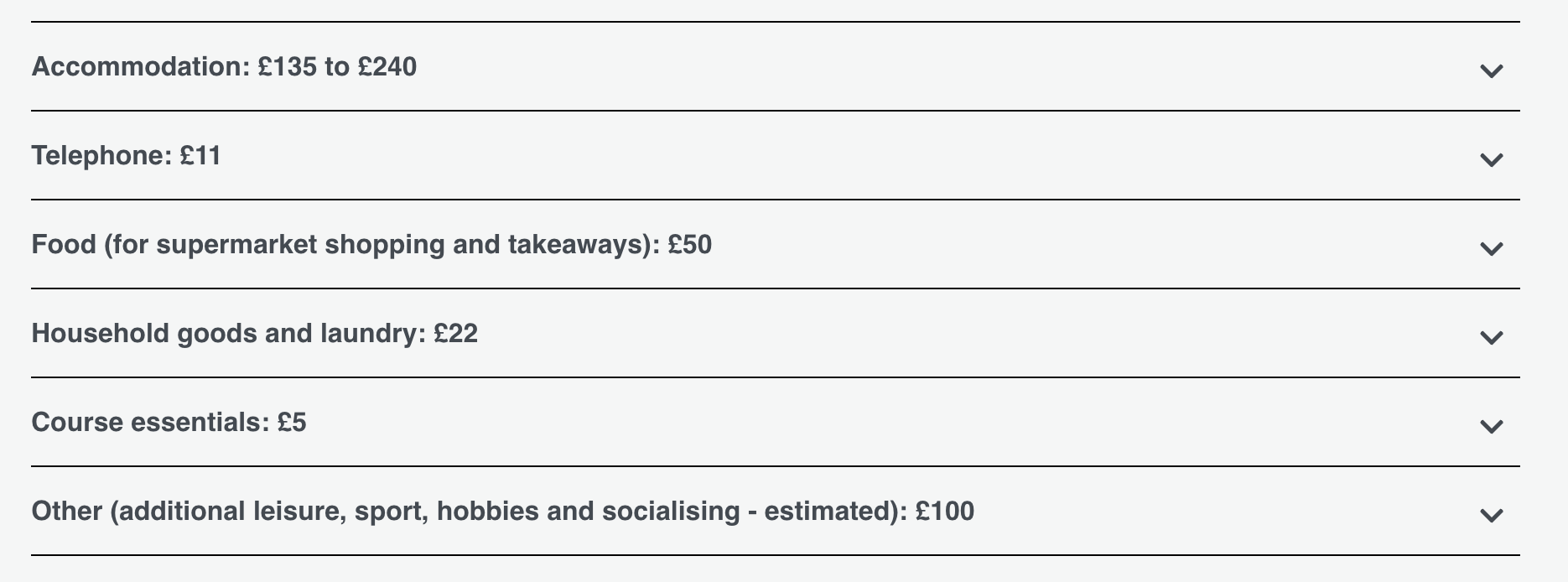

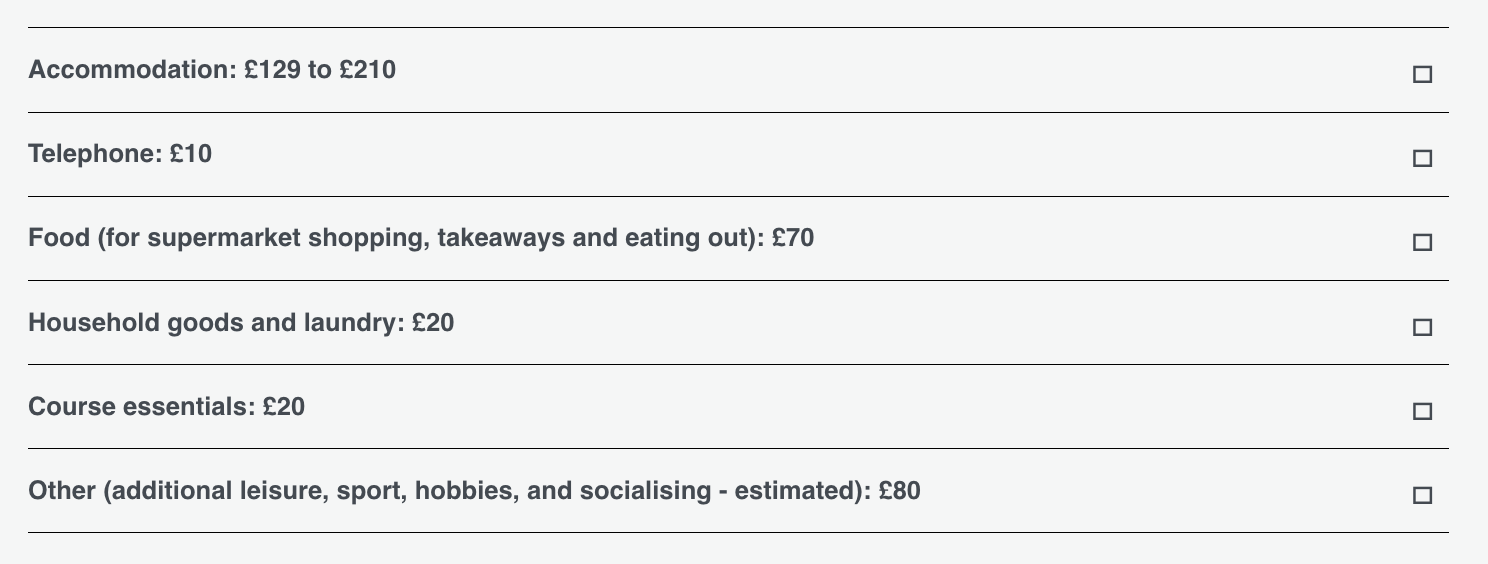

Or unsourced tables like this, where somehow student costs have started to fall. I want to move there!

2024. Here’s 2025:

The long arm

The good news for prospective students – and the bad news for universities – is that this is all now going to have to change.

Looking at all of this through the lens of the new Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers (DMCC) Act, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that universities have been sailing remarkably close to the wind – and that the wind direction has now changed dramatically.

Under DMCC, the systematic provision of outdated cost-of-living information would likely constitute a serious breach of consumer protection law. The Act makes it automatically unfair to omit material information from invitations to purchase – and there’s little doubt that accurate living costs are material information for prospective students making decisions about whether and where to study.

Crucially, there’s no longer any need to prove that students were actually misled by the information, or that it influenced their decision-making. The omission itself is the problem.

The legal framework has fundamentally shifted in universities’ disfavour. The scope of what counts as material information has expanded beyond those categories defined by EU obligations, while misleading actions are no longer restricted to predefined “features” of a product or service.

Instead, any information relevant to a student’s decision can now trigger a breach – meaning universities can no longer rely on narrow, checklist-based approaches to compliance. Outdated transport costs, inflated claims about local entertainment prices, or misleading accommodation estimates all fall squarely within this expanded scope, even though they might previously have been considered peripheral to the core “product” of education.

The Act has also lowered the threshold for proving breaches of professional diligence. Previously, universities might have argued that minor cost discrepancies didn’t cause “material distortion” of student decision-making. Now, practices need only be “likely to cause” a different decision – shifting the focus from proving impact to ensuring accurate practice from the outset.

The Act explicitly recognises that certain groups of consumers are particularly vulnerable, and that practices which might not affect others can cause disproportionate harm to those groups.

International students – who rely heavily on university cost estimates for visa applications and have limited ability to verify information independently – are a textbook example of vulnerable consumers. So too are first-generation university students, those from lower-income families, and young people making major financial commitments for the first time. The Act requires universities to proactively identify and mitigate risks to these vulnerable groups as part of their duty of care.

The Competition and Markets Authority now has significant new enforcement powers, including the ability to impose civil penalties of up to 10 per cent of an organisation’s turnover and to hold corporate officers personally liable where they have consented to or negligently allowed breaches to occur.

Given the sector-wide nature of these problems, and the ease with which accurate cost information could be obtained and maintained, it would be difficult for universities to argue that continued reliance on years-old estimates meets the standard of professional diligence now required by law.

The sector has had years to get this right voluntarily. With enhanced legal obligations, fundamentally expanded definitions of what constitutes actionable information, lowered thresholds for proving breaches, and much sharper enforcement teeth now imminent, universities that continue to present outdated or inaccurate living costs as current information may find that their casual approach to accuracy has become a rather expensive mistake. Their mistake.

University’s say what they want on virtually everything. There is no effective regulation by the OfS, DfE , CMA or anybody else. They will never be held to account for claims about the cost of living as a student. Best to ignore any declarations and just rely on common sense. The maximum maintenance loan is nowhere near enough, but it shouldn’t be increased as this just leads to more debt piled on to our young adults to carry through life. Parents and students just have to get real and accept that they have to supplement income by parent handouts or… Read more »

How does that work when parents are unable to supplement income or a student finds themselves having to choose between 3 meals a day or attending their seminars, as many already do? You’re essentially saying that only people from a wealthy background should be able to go to university. I think it’s better to give people more debt than take away that option entirely.

I agree, Lola. If I had not been given more debt, I never would have been able to attend university. My parents couldn’t supplement my life. If we ‘just accept’ this, university will only be for the affluent.

What is “accurate” and how can HEIs possibly know what all students will need over a period of years?

Affordability of study is a top priority for prospective students, and as such it’s a critical service universities need to be providing to their key target audience. First step would be for universities to recognise this as a service they need to provide so that they can begin to manage and monitor it responsibly.

Universities are only obliged to provide transparent and accurate information about course related costs and accommodation they provide. For example, stating whether or not wifi is included in rent. Unless it is compulsory to watch TV, this type of information does not have to be kept up to date. When a University says it is inclusive it does not mean that it is offering an “all inclusive” package.

Even if we set aside the morality of that position, it’s wrong. Under DMCC material information includes not just course fees and accommodation, but any information that is likely to influence a student’s decision to study at a particular university. That includes transport costs, food, utilities, gym fees, and yes – even TV licence fees if included in student budgeting pages. The law has shifted from a narrow checklist approach to a broader one: what is relevant to a consumer decision. Universities must now take particular care when information is directed at vulnerable groups, such as international students or first-time… Read more »

Entirely right to stress the impending huge significance of the DMCC and especially re ‘omissions’. Us must get their consumer protection act together; and not just in the areas Jim usefully highlights but re, eg, seminar sizes, feedback arrangements, remote delivery of T. In short the S now has an enhanced legal right to far more and much more accurate data on what he/she is buying for £9500 pa.

The law hasn’t changed – it’s still all based on the 2015 consumer rights legislation. If Jim is right, lawyers will advise universities not to give any guidance at all on living costs other than actual course related costs and the charges for their own services including accommodation. Of course, any fines levied on HEIs will ultimately be paid for by students and staff, one way or another.

https://wonkhe.com/blogs/honesty-and-accuracy-is-about-to-get-even-more-important/

https://wonkhe.com/wonk-corner/consumer-protection-law-has-changed-and-the-changes-apply-to-universities-now/

(The law has changed)

Yes it has indeed! CRA15 is greatly enhanced by DMCM.

Hi Jim, I work for an SU and a while back (I think on the prompting of your last article on this topic), I spent a couple of days really trying to pin down student budget figures for my city so I could make sure university figures weren’t outdated- and I found it a real struggle. I could often find what seemed to be up-to-date data, but then it would wildly contrast with other up-to-date figures (i.e one source saying students spend £126/week on eating out and take-aways, another £10). The other thing I could think to do would be… Read more »

One of the large issues here is resource. With university marketing teams getting smaller (speaking for my university where multiple vacant marketing and content posts are on hold and will continue to be for the foreseeable future) there are choices to be made about resource allocation. Promoting an open day to get visitors through the door will often override pieces of work like this that are undoubtedly critical. Universities could work collectively here to minimise resource – whether in the same city / region, but if those relationships aren’t there then I can see some universities being at risk.