Gara (problem-solving abilities), Urra (wisdom and creativity), Raga (courage and resilience), Zargo (health and success) and Czarodoro (overcoming personal limitations).

Oh, and Jarga (the cleansing of negative energies) and Jarun (karmic balance).

No, it’s not Poland’s graduate attributes framework – it’s a set of new age “agmas” that Polish Eurovision entrant Justyna Steczkowska starts chanting in the final 30 seconds of her song “Gaja”.

It says here that it’s a song about primordial Earth goddess Gaia from Greek mythology, narrating a transformation from pain to empowerment while symbolizing both sorrow and the cleansing of past wounds.

It may well be, but made up words is really just a remixed Eurovision trope – it’s Diggi-Loo Diggi-Ley or Wadde hadde dudde but in a minor key with a straighter face.

In this year’s Wielki Finał Polskich Kwalifikacji (“The grand finale of the Polish qualifications”), I was rooting for the much more interesting Lusterka, performed by “Podlasie Bounce” act Sw@da x Niczos.

It’s sung entirely in Podlasian – an East Slavic microlanguage that’s a mix of Belarusian and Ukrainian which at one stage caused Belarusian authorities to label the act as “extremist” over promoting cultural narratives counter to the regime’s ideology:

If you’ve been to our concert, you know that our music is about dancing out emotions that are shared by all people, regardless of language, skin color or worldview.

Sadly rather than travelling to Basel on May 17th, they’ll be headlining the Gdańsk Juwenalia – the biggest student festival in northern Poland, where the SUs from six universities join forces to organise two huge nights of music, along with a “talkStage” featuring engaging interviews with notable guests, a “Student Zone” where the public can learn about students’ projects and research, a massive public barbecue and an “integration of faculties and organizations zone”.

The big student cities of Lublin, Wrocław and Kraków have their own earlier in the month – and now having seen a couple in action, they really are astonishing.

Bawcie się dobrze!

Every May, pretty much every university town and city in Poland has a Juwenalia. Loosely translated as “festival of youth”, it’s a cultural institution that balances celebration with resistance, tradition with innovation, and individual expression with collective identity.

And its evolution over the years mirrors Poland’s own journey – from medieval scholarly tradition through communist oppression to contemporary democratic renewal.

Across four zones scattered around Kraków, students will have the opportunity to hear their favorite artists live, compete in various sports competitions, and integrate with new friends through a whole range of other activities and projects.

What makes it fascinating isn’t just its scale, or how long it’s been around, but how it both reflects society and kicks off change. When free expression was dangerous, Juwenalia gave students a space where they could voice critique through metaphor, satire, and symbolism. And when tragedy struck – like when anti-communist student activist Stanisław Pyjas was murdered in 1977 – it transformed into a powerful way for students to stand together against injustice.

You can trace Juwenalia back to medieval Europe, where universities functioned as semi-autonomous communities with their own customs and rituals. In Poland, that first took shape in the 15th century at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, where students would organise processional performances featuring musicians and mimes.

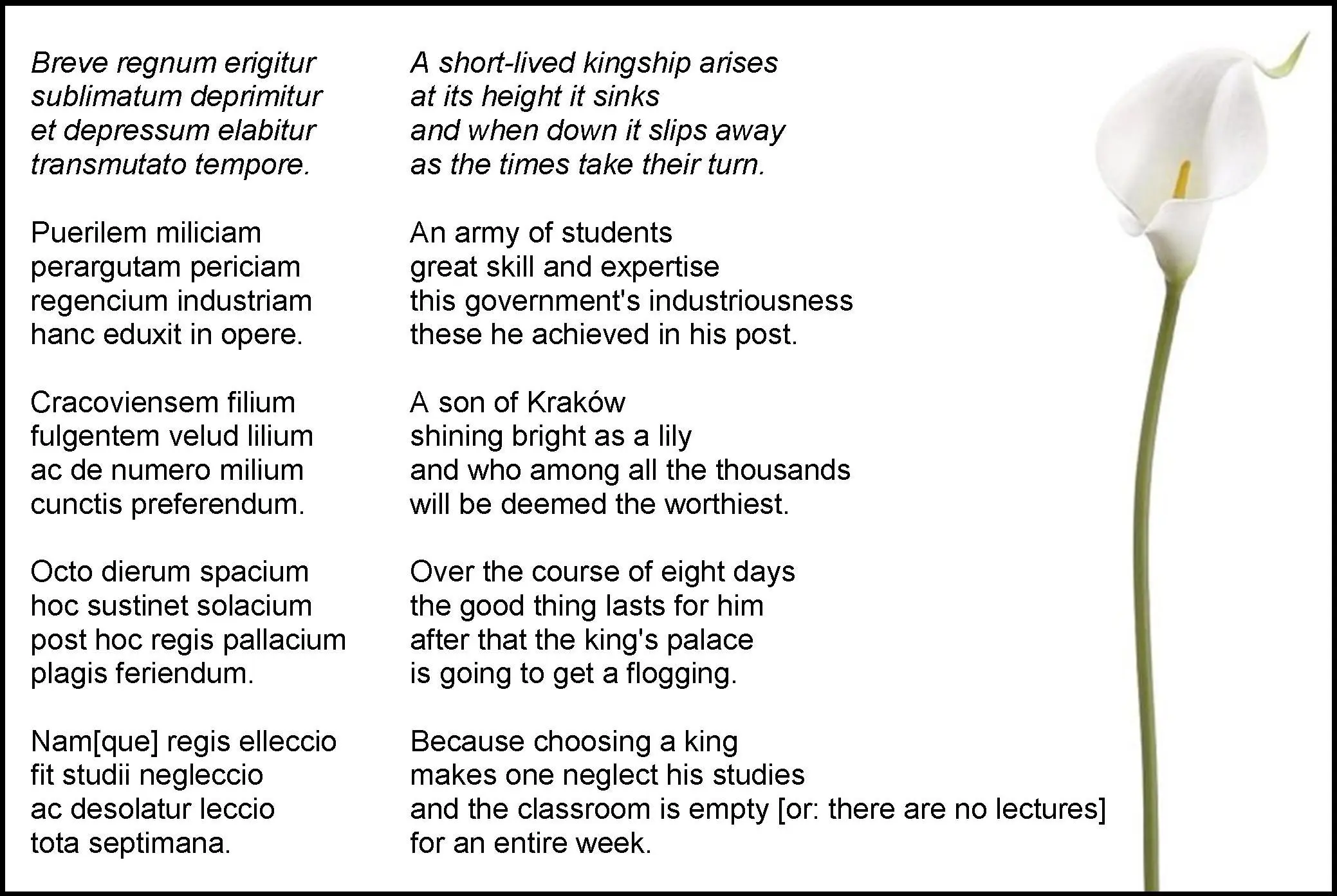

Breve regnum erigitur is a song from the mid-15th century, sung by students in Kraków during their annual week of student rule, where there was a reversal of hierarchy – students elected their own “king”, took over the university and abolished lectures.

But the modern form of Juwenalia really came together in 1964, during celebrations marking the 600th anniversary of Jagiellonian. That year, students processed from Wawel Castle to Kraków’s Main Square under the slogan: “From Casimir the Great to Casimir the Better” – a nod to both the university’s founder, King Casimir the Great, and the institution’s then-rector, Professor Kazimierz Lepszy. And it quickly spread both around the city and the country.

What always interests me about the student traditions we see across Europe is how they mix elements from multiple traditions, and from both the past and the present. In Juwenalia you can see echoes of ancient Roman festivals like the Bacchanalia and Saturnalia, medieval carnivals with their temporary suspension of hierarchy, and academic ceremonies reflecting the special status of university communities throughout European history.

It gives Juwenalia a really interesting cultural vocabulary – one that proved pretty adaptable during each of Poland’s complex political transformations. Hence during the communist era, when public expression was tightly controlled, the festival’s traditional elements provided a framework within which students could engage in subtle forms of resistance and critique.

That Juwenalia survived and thrived under communism tells us a lot about its cultural significance. The regime, wary of student gatherings, recognised the political cost of suppressing a beloved tradition. Students, meanwhile, used the festivals as opportunities for creative dissent, embedding political commentary in performances, costumes, and slogans that were just ambiguous enough to escape censorship.

Universities are always caught between tradition and change – and the tension between celebration and dissent reached its peak in 1977, when a tragedy transformed the nature of Juwenalia and kicked off a new phase in student resistance to communist rule.

Stanisław Pyjas and the Black March

On 7 May 1977, Kraków awoke to shocking news. Stanisław Pyjas, a 24-year-old student of Polish literature and philosophy at Jagiellonian University, had been found dead in a tenement stairwell at 7 Szewska Street in the city centre. His body lay in a pool of blood, and officials quickly declared the death an accident – claiming Pyjas had fallen while intoxicated.

But students knew better.

Pyjas and his friends were literature enthusiasts with countercultural leanings who had connections to the KOR (Workers’ Defence Committee). They gathered signatures defending arrested workers, and organised little protests against government repression. That activism had put Pyjas under intensive surveillance by the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (SB), the communist secret police, who had begun monitoring his movements and issuing threats.

The official explanation for his death didn’t add up for those who knew him. One of his friends bribed a morgue worker to view the body privately – and what he saw confirmed his suspicions:

I saw the face of a man who’d been beaten to death. Staszek’s death changed everything.

News spread rapidly throughout Kraków’s universities. Within hours posters appeared in dormitories with an appeal – urging students to wear black, observe mourning, and convert the upcoming Juwenalia festivities into protest. The result was the “Black March” or “Czarne Juwenalia” of 15 May 1977.

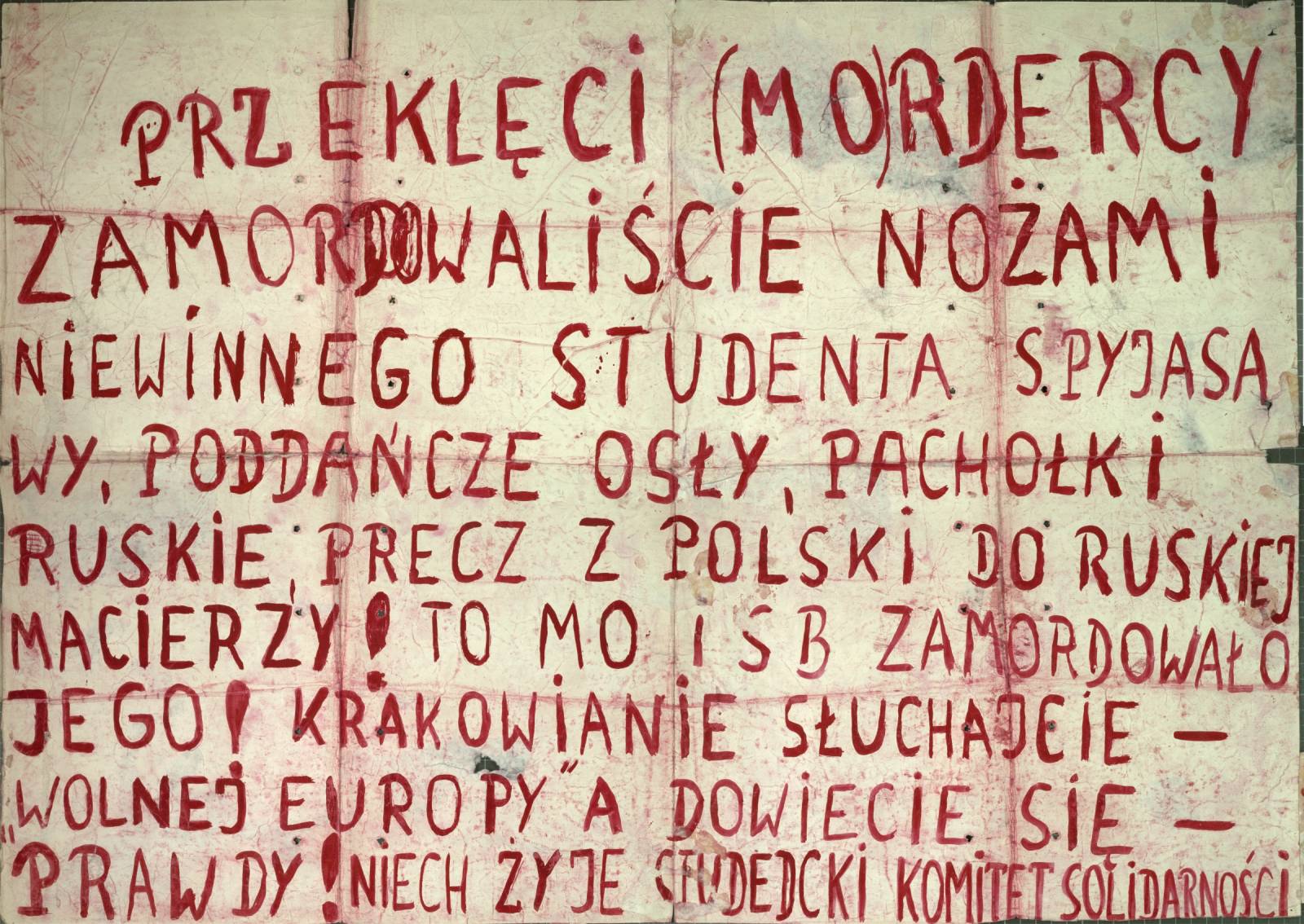

CURSED (MURDERERS) You murdered the innocent student S. Pyjas with knives. You submissive donkeys, Russian lackeys – out of Poland, back to your Russian motherland! It was the SB (Security Service) that murdered him! Cracovians, listen to “Radio Free Europe” and learn the truth! Long live the Student Solidarity Committee!

Instead of the traditional carnival, thousands of students dressed in black flooded the streets following a memorial Mass at the Dominican church. They processed in silence through Kraków’s Old Town, many wearing black armbands and carrying small black flags.

As bystanders watched the procession, the public spontaneously joined in. Marchers made their way to Wawel Hill, where Staszek’s friends publicly denounced the official cover-up and demanded justice. And as speakers said the word “solidarity,” someone in the crowd shouted, “Solidarity with whom?!” The reply: “Solidarity with ourselves!”

That night, ten students founded the Student Committee of Solidarity (SKS) – the first independent student organisation in communist Eastern Europe, predating the broader Solidarity movement by three years. The regime had intended Pyjas’s death to intimidate students into silence – but instead it triggered a new phase of resistance:

Staszek’s death was meant to scare us, but it created a different reaction – a process of overcoming fear.

It all puts a particular spin on “by students, for students”.

Przez studentów, dla studentów

Today the scale of these things is astonishing – in Kraków alone, over 500 students are directly involved in organising the festival, almost all of which do so as unpaid volunteers, and tens of thousands of students and guests will take part.

Making that happen across the city’s ten universities was not easy, but in 1997 the Porozumienie Samorządów Studenckich Uczelni Krakowskich established a structure for coordinating volunteer efforts across multiple institutions – and has gone on to be a vehicle to enable civic participation in the city.

Each SU appoints a student Juwenalia Director responsible for partnerships and logistics, and then specialised teams handle everything from stage management and artist relations to security and waste management. The MS Patrol from Miasteczko Studenckie AGH, for instance, assists with security, logistics, and clean-up – developing skills in crowd management and emergency response that you just won’t get from an exam or a group project.

These are real, authentic learning experiences where students manage budgets, negotiate contracts, coordinate teams, and develop sophisticated crisis management protocols. It also brings students together across different departments, years, and even universities:

For those few days, we’re not competing – we’re all just students celebrating together. It’s like the walls between our universities come down.

Talking to some of the organisers, there’s a strong sense that unlike many university traditions that reinforce existing social hierarchies, Juwenalia creates opportunities for participation across academic disciplines, year groups, and socioeconomic backgrounds. The temporary “student republic” established during the festival allows for experimentation with new social roles, relationships and responsibilities.

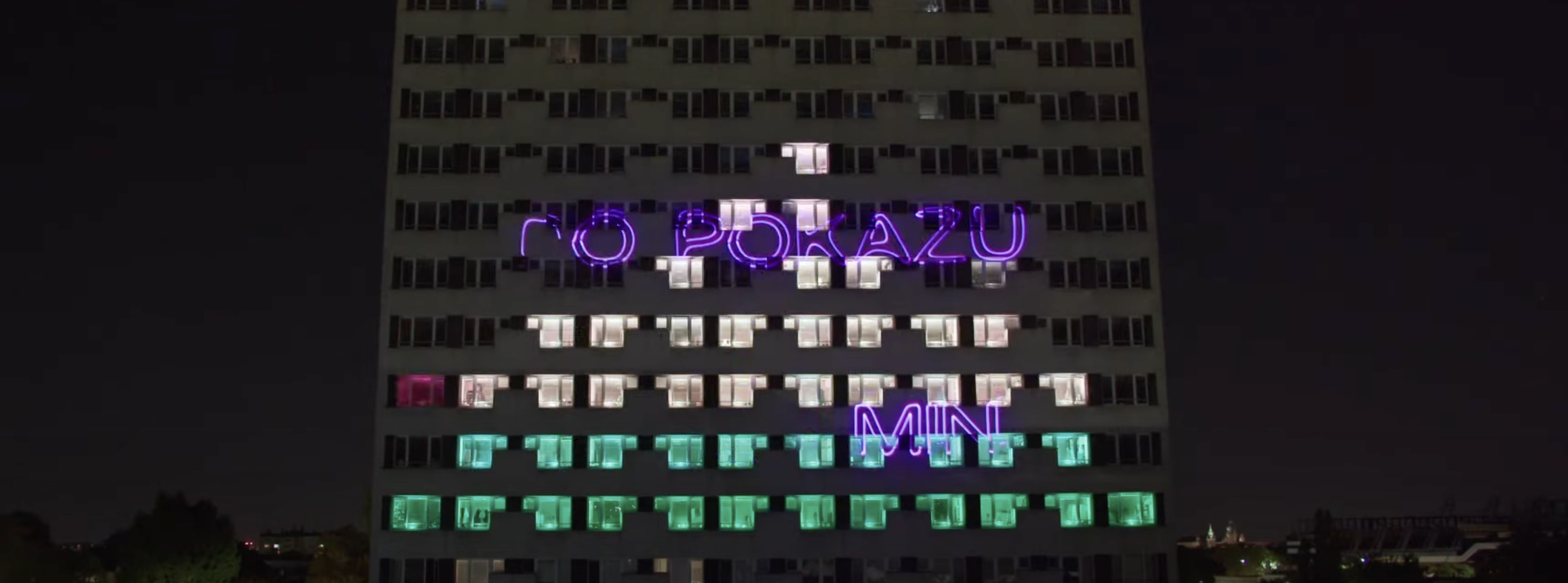

As well as multi-stage concerts, a clutch of side projects and peripheral events populate the Juwenalia calendar and expand the opportunities for connection. In Krakow right at the start of the month, students put on a light show that transforms their dorm windows into a visual spectacle, after which there’s a quiz, a Disco Roller Rink and a Karaoke competition. Students can join the Blacksmith’s Run, a race from the main building to the 12th floor of Student Hall No. 1, or the Sports Festival at the Green Zone, which includes volleyball, handball, and strength challenges.

A few days later the OSPK Day combines a BBQ, outdoor cinema, and mechanical bull riding, while the Juwe City Game sends teams racing through the Old Town to complete puzzles and challenges. There’s also an Outdoor Cinema, a chess tournament, the JuweCanDance competition, an Artistic Evening offering painting, crocheting, and ceramics, and the big Juwe Parade sees students from all universities march through the city in costume, all starting with a hearty polish Juwe Breakfast at one of the student venues.

And every single event is run by student volunteers.

The keys to the city

At each Juwenalia, power reversal is both practical and symbolic. The central ritual – where the Mayor hands over the city’s keys to students – embodies what Mikhail Bakhtin called the “carnivalesque”, a temporary inversion of established hierarchies that simultaneously challenges and reinforces social order.

That ritual traces its lineage to medieval traditions where the world was “turned upside down” during carnival periods, with fools crowned as kings and ordinary rules suspended. In contemporary Juwenalia, the inversion takes multiple forms – colourful processions disrupting urban space, symbolic control of city centres, and temporary transformation of university and civic leadership roles.

During the communist period, the ritualistic inversions carried critique – the “taking of the keys” was a metaphor for broader democratic aspirations. Under democracy, the same ritual continues, but it’s now a celebration of student autonomy within an accepted constitutional order. The country – at least for the month of May – believes in its students, and gives them control.

In most cities, a huge student parade following the key thing features students in elaborate costumes that can carry satirical or political messages. During the communist period, these often took the form of what James Scott called “hidden transcripts” – messages encoded in performance, costume, and symbolic gesture that conveyed political critique while maintaining plausible deniability:

Cabaret humor dominated and allusiveness and metaphor were everywhere. Every gesture, slogan, and inscription referred to the political reality of the time.

In today’s democratic Poland, the politics takes more overt forms – there’s bits of environmental activism, support for social causes, and commentary on current political debates – particularly in protest at the populist government in the last decade. The temporary claiming of urban space also turns streets and squares into sites of student expression – asserting the right of young people to help shape public debate.

That cultural and political dimension then extends beyond the festival period through the organisational structures and networks it creates.

The Student Committee of Solidarity that was founded during the Black March of 1977 evolved into a big political force, with many of its members later playing important roles in the broader Solidarity movement and Poland’s democratic transition.

Even now, the organisational capacity developed through Juwenalia planning translates into other forms of student activism and civic engagement. The skills in coordination, communication, and coalition-building developed through festival organisation become valuable resources for addressing campus and community issues throughout the academic year – and in later life.

Economic impact and commercialisation

For those that were around during communism, it’s all a bit commercial these days. Budgets run into millions of PLN per institution – and so need multiple revenue streams, including university allocations, ticket sales, sponsorships, and partnerships with local businesses on the other side of the excel sheet.

Wandering around this year’s festival grounds in both Kraków and Lublin, the commercial presence was unmistakable – sponsor logos on stages and barriers, branded merchandise filled the JuweSklep, and promotional activities populated the festival zones.

But students know how to get the balance right. One of the student “External Cooperation Coordinators” I met rabbitted on about how maintaining an authentic character remained a priority:

We’re selective about partnerships. We look for sponsors who understand and respect the cultural significance of Juwenalia, not just those with the biggest budgets.

The economic impact extends beyond the festival itself. It creates significant value for local economies, particularly in cities where the student population forms a substantial segment. Hotels, restaurants, bars, and taxis all experience increased demand during the festival period. The influx of visitors – students from other cities, alumni returning for the celebrations, family members, and tourists attracted by the festivities – creates a huge multiplier effect that benefits the broader urban economy.

And of course that also all provides valuable learning opportunities for student organisers, who pick up practical experience in budget management, contract negotiation, partnership development, and financial accountability.

The technical infrastructure alone is impressive. At the UJ Żaczek zone, the main stage is a massive structure – 32 metres wide, 23 metres deep, and 12 metres high – requiring five trucks of equipment including sound systems, lighting rigs, and LED screens.

And environmental considerations have become increasingly important in recent years – students arrange additional cleaning of streets and sidewalks around campus to maintain good relations with neighbouring communities and demonstrate environmental responsibility.

You wonder why so many students are involved – but plenty of the Juwenalia volunteers were keen to chat about their personal and professional development. One of the logistics coordinators I met said that having studied project management theoretically, she found herself applying these concepts in real-time, managing a team of 15 volunteers coordinating everything from equipment delivery to artist transportation:

The theoretical frameworks make sense only when I have to apply them under pressure. The case studies… they cannot replicate the feeling of solving problems when thousands of people are waiting for a concert to start.

But benefits are never to be confused with motivation. The student who was serving me beer in the bar on her 14th hour at work (for free) (the work, not the beer) at first struggled to understand why I was asking the question. But she was clear about the answer:

When you first come, you wonder if one day it could be you behind the walls helping it to happen. Everyone looks forward to it. It’s ours.

The practical education thing extends across disciplines too. Marketing students gain hands-on experience developing promotional campaigns and managing social media platforms that reach thousands of followers. Engineering students apply technical knowledge to stage construction and sound system setup. Economics and management students develop budgeting and financial reporting skills managing six-figure budgets.

And the experiences often translate directly into career opportunities. Juwenalia volunteers leverage their festival experience to get positions in event management, marketing, public relations, and arts administration. Others apply the leadership and teamwork skills in entirely different sectors, noting that employers value the practical problem-solving abilities developed through festival organisation.

The professional networks formed during Juwenalia are also critical. Volunteers form connections not only with fellow students but also with university managers, local business leaders, government officials, and cultural professionals, and the relationships persist beyond graduation, creating mentorship opportunities and professional referrals that can rocket boost their career.

Popping off

But maybe most importantly, Juwenalia participation seems to help students discover and develop capabilities they didn’t know they had. Watching one of the Promotion Coordinators directing her team, it was hard to imagine that she had once described herself as “very shy”:

I think that Juwenalia has made me develop communication skills I didn’t think I had. I am thinking about careers I would never have thought of before.

And for students just enjoying it all, there are emotional and transformative experiences for them too:

Singing with six thousand people, in beautiful weather, on campus at the best time of their lives – that’s the experience!

The sentiment was palpable during top pop star and headliner Zeamsone’s set at the UJ Żaczek Zone. As thousands of voices joined in with the lyrics, for many first-year students in attendance, this was probably their first experience of true university community – a powerful flip from the often isolating experience of contemporary academic life.

Sociologist Émile Durkheim called moments like that “collective effervescence” – a heightened sense of emotional energy and group solidarity that emerges from shared ritual experiences. These are moments that can profoundly alter participants’ sense of identity and belonging, creating lasting emotional connections to both the university community and the broader cultural traditions it embodies.

What a shame that the only ones left I can think of in UK HE are graduation ceremonies – held once it’s all over.

Civic dimensions

I should talk about the civic stuff. Juwenalia has what one of the organisers I met called a “complicated” relationship with their host cities – it transforms urban spaces, disrupts normal patterns of city life, and can annoy plenty of the locals.

But the symbolic “taking of the keys” is partly about recognising legitimate stakeholders in urban governance. Mayors turn up, do the speech and get the press coverage partly because they were probably in the parade in their youth – and partly because they need the votes.

In Kraków, festival organisers begin meeting with police, city guards, and fire services months in advance, developing detailed security and logistics plans. The parade, which processes through central Kraków to Plac Szczepański, requires particular attention to traffic management, crowd control, and public safety. They are interactions that create excellent opportunities for students to engage with civic institutions and processes – building their “linking” social capital in the process.

From the city’s perspective, Juwenalia offers big benefits. These are events that showcase the area’s educational institutions, attract thousands of visitors, generate significant economic activity, and contribute to a city’s urban culture.

They also act as recruitment and access tools for prospective students, offering up a glimpse of contemporary student culture and creating opportunities for intergenerational interaction. Almost everyone I met that was organising Juwenalia had sneaked into one before they were a student – or at least dreamed of doing so.

They also promote higher education more broadly. On display is student creativity, leadership, and community spirit – smashing negative stereotypes about student life and showcasing the diverse talents developed within university communities.

I tried very hard to find negative or nasty local press coverage about Juwenalia. I couldn’t find any.

The soul of student culture

If I think about “May Ball” culture in the UK, I just become miserable. Like so much of what’s rotten about higher education in the UK, our version of student spring celebrations all roots back to Aldi versions of Oxbridge – lavish all-night parties, black-tie dress, fine dining, fireworks, open bars, boorish boys burning £20 notes in front of the homeless, and allegations of sexual misconduct to be handled in the weeks afterwards.

Juwenalia couldn’t be less exclusive, involves the public, is usually cheap (and often free), is deliberately diverse and is about subverting power hierarchies, not reinforcing them.

With some notable exceptions, outside of the upper echelons, big tentpole student events with big tents and big budgets generating big problems are all but gone now. Maybe the cost of alcohol did it, or health and safety, or student diversity, or the professionalisation of SUs, or the collapse of our domestic music industry, or cost of living – maybe all of those. Maybe they’re really still there – just smaller and hidden. But what I’m sure of is the lack of what Juwenalia is really there to do – to maintain, promote and develop what we might call student culture.

As things started to get really difficult for students post-pandemic, I think the assumption was that once the scarring of isolation was gone, things would bounce back. In some ways they have, in some ways not – but what’s still missing is what has been missing for a long time.

Back in Krakow, the Jagiellonian University Students and Graduates Foundation emerged from Poland’s transformative post-1989 democratic and economic changes, and revived a cherished 19th-century tradition of student mutual aid societies – it dedicates itself to improving the social and living conditions of the university’s academic community while championing cultural, scientific, and artistic initiatives.

It’s funded via the revenue generated from activities like the halls of residence that it owns, and donations – and offers scholarships, facilitates employment opportunities, and supports students facing financial hardship. It also co-finances academic projects, cultural events, and sports activities, publishes student magazines, and runs international exchange programmes.

And its governance reflects a collaborative balance between the university and its students – on its Board are both academic staff and students elected by the council of the SU. Crucially, at arm’s length from the university itself and a little separate from the representative role of the SU, it takes on much of what we might in the UK describe as professional “student services” – largely via the facilitation of volunteer-led project work.

Just up the road, the biggest student foundation in the city is called ACADEMICA, established in 2000 and spearheaded as a partnership between the SU’s council and the vice-rector to support student activities, initially managing four student clubs and the university canteen. It now operates cultural initiatives, various student study halls and facilities, Poland’s biggest student nightclub, and a mini-brewery and a bistro – and both employs over 500 students directly and facilities about 3000 in volunteer roles.

Its “host” SU at the AGH University of Science and Technology is like many of the others we saw in Poland in January – it runs a huge Board Games night runs weekly, there’s an adaptation camp and rights talk for new students, and an AI Days conference created by a team of students with sessions on the importance of basic AI knowledge for future graduates.

Goddamn we’re greatness

Doing things for others, rather than helping them do things for themselves, is deep inside the UK’s culture of charity. It takes on a momentum – it creates sector conformity, sets up recognised careers, generates LinkedIn posts, demands spend on strategic away days, and has a language and culture concerned with measurement, metrics and justification. It also creates an expectation – that other people will do things for students – and that their job is merely to moan when the providers inevitably over-promise and under-deliver.

There are lots of things that are great about that culture too – but I’ve been surprised about the post-pandemic acceleration of a process in which both universities and their SUs have so readily jumped on the bandwagon of assumption that students will never do anything for themselves ever again. They’ve got no time, they’ve got no money, they’ve got no social skills, so we’ll have to do it all for them, and we’ll feel good about it when we put on that game of rounders or that crochet class.

Letting go – being deliberate about creating the structures, scaffolding and cultures where students can do things for themselves – is tough. Professionals are proud. But the idea that in a mass system you can build social capital by injecting transferable skills into what contact hours are left, or that you can build confidence by having the odd student staff member around to help with the admin, is all relative obvious nonsense.

Being ambitious about student creativity and control can’t just be about what they do academically. And having a vision for student culture – one that is social, enabling, contributory, and stretches them to find the time and resources to inherit and shape it – will at least make them angrier about the fact that some of their friends don’t have the time or money to take part.

As Magdalena Herman, President at Jagiellonian’s SU put it:

And I have to tell you that when I look at all these people, and I’m like, whoa, we did this all by ourselves? And we are only 24 years old, you know? And we’re like, how? God, damn, we’re great.