In a document called “Opportunity, growth and partnership”, there’s no shortage of partnerships that Universities UK identifies as being important to foster and maintain.

Its blueprint mentions NHS trusts, essential for student mental health. There’s Skills England for the need to tackle skills shortages. There’s the Turing Scheme for the development of global awareness, understanding and competencies that will allow the UK to play a full and proper role globally.

There’s also partnerships with SMEs, the Home Office, local authorities, Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), Local Growth Partnerships, Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), the Department for Business and Trade, the Department for Education, the British Business Bank, Horizon Europe, Mayoral Combined Authorities (MCAs), Study UK, international universities and research bodies, Institutes of Technology (IoTs), further education providers, civic institutions, and transnational education partners.

The partnership required with students to generate educational outcomes? Not so much.

Ever since students started to pay for their education individually, there’s been a rearguard action against seeing students as consumers – and the blueprint argues that a “fundamental rethink” of the purpose of the regulation of higher education requires a reframing of the “current focus” on consumer protection towards a recognition of the “public benefits of higher education and its close links with research”.

But not only would most students struggle to recognise the idea that there is, or has been, a focus from England’s regulator on students getting what they were promised, at least when folk argue against it it’s usually to promote the idea that students should be seen as partners.

That framing tends to stress a need to consider what it is that universities need students to (be able to) do, and what the scaffolding, funding for organisations or support for students might need to look like for them to be able to do it in an organised fashion.

Yet in a list of “features” that the blueprint’s authors believe all students should be able to expect from their university, their agency is reduced to a sentence that is decidedly consumerist in nature:

…clear processes and points of contact for students to use within universities for addressing issues and providing feedback.

I’ve never been convinced that partnership and consumer rights should be seen as mutually exclusive by UK HE. Of course it is the case that students are not “buying” a degree – but they are buying a set of services and supports that, coupled with their effort and talent, can get them a degree. Certainty over the former is what enables the latter.

And so in a context where universities’ ability to rely on students to help create their experience and outcomes is as restricted by funding as the institutional side of the bargain, the absence of meaningful material on their role suggests there is more work to do to secure the sector’s success.

Expectation management

Doing so is difficult when both the present and the future are characterised by diversity – and so it’s interesting to consider those features that the commission believes all students should be able to expect from their university, as opposed to those that might vary from provider to provider. That’s because:

…a clear, consistent offer from universities is important, so that students have a good understanding of what they can expect during and after their studies.

That is boiled down to seven components as follows:

an environment where every student can be inquisitive, intellectually challenged and benefit from the diversity of different perspectives.

- That’s the free speech line;

high-quality courses to provide students with the necessary skills and knowledge for further study or professional careers, both in the UK or internationally.

- That doesn’t especially mark out HE from other forms or levels of education, but you can see what they’re getting at;

transparent information on the typical hours of in-person instruction, online instruction and independent study expected on a course, including the factors that may affect this.

- That’s already a consumer protection law requirement, although it goes further than the teaching;

student services covering academic skills support and advice on navigating the wider student experience.

- That frames mental health support as study support – a line many in the sector would love to hold on to, but one that’s been passed some time ago in expectations terms;

employability and careers support, including work-experience opportunities accessible to all students, and dedicated careers support for students while they are at university and for a total of five years post-graduation.

- Work experience opportunities for all feels like a stretch for which there is insufficient additional material elsewhere, and “five years” commitment feels oddly specific;

clear processes and points of contact for students to use within universities for addressing issues and providing feedback.

- That feels like the “students’ union, but let’s not actually say students’ union” line – and waters down what SUs do in the process;

accommodation availability that is informed by the size and shape of the student population, and engagement with local partners to meet demand – this can include working with other local universities, local authorities, and the private rented sector.

- That’s reflected in Universities UK’s own guidance notes on the issue – but we are obviously some distance from it being a reality.

Funding our present

Let’s imagine that the list as stated is the right one. To have the time to be inquisitive, intellectually challenged and benefit from the diversity of different perspectives, to have the money to live in accommodation that is informed by the size and shape of the student population, or even to take advantage of what would presumably often be unpaid work-experience opportunities, students will need the resource.

If we just examine the funding question alone, pretty much the only proposals in the blueprint are to reinstate maintenance grants for (undergraduate) students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds (to an unspecified level), and increase maintenance loans in line with inflation.

If it was the case that we could say, hand on heart, that those two proposals would allow students to take advantage of the universal offer, the proposals would make sense.

But without any underpinning analysis of need or means, the twin proposals are meaningless. For undergraduates, there’s a yawning (and growing) poverty gap between students and the universities they attend. Both PGTs and PGRs might be wondering how those proposals would assist them. And anyone on a programme requiring more time (perhaps with heavy lab or placement requirements), any student whose circumstances restrict things (living in London, having kids) or any student not able to complete at the same pace (those experiencing setbacks, many disabled students) will find the blueprint on their side of the partnership wanting.

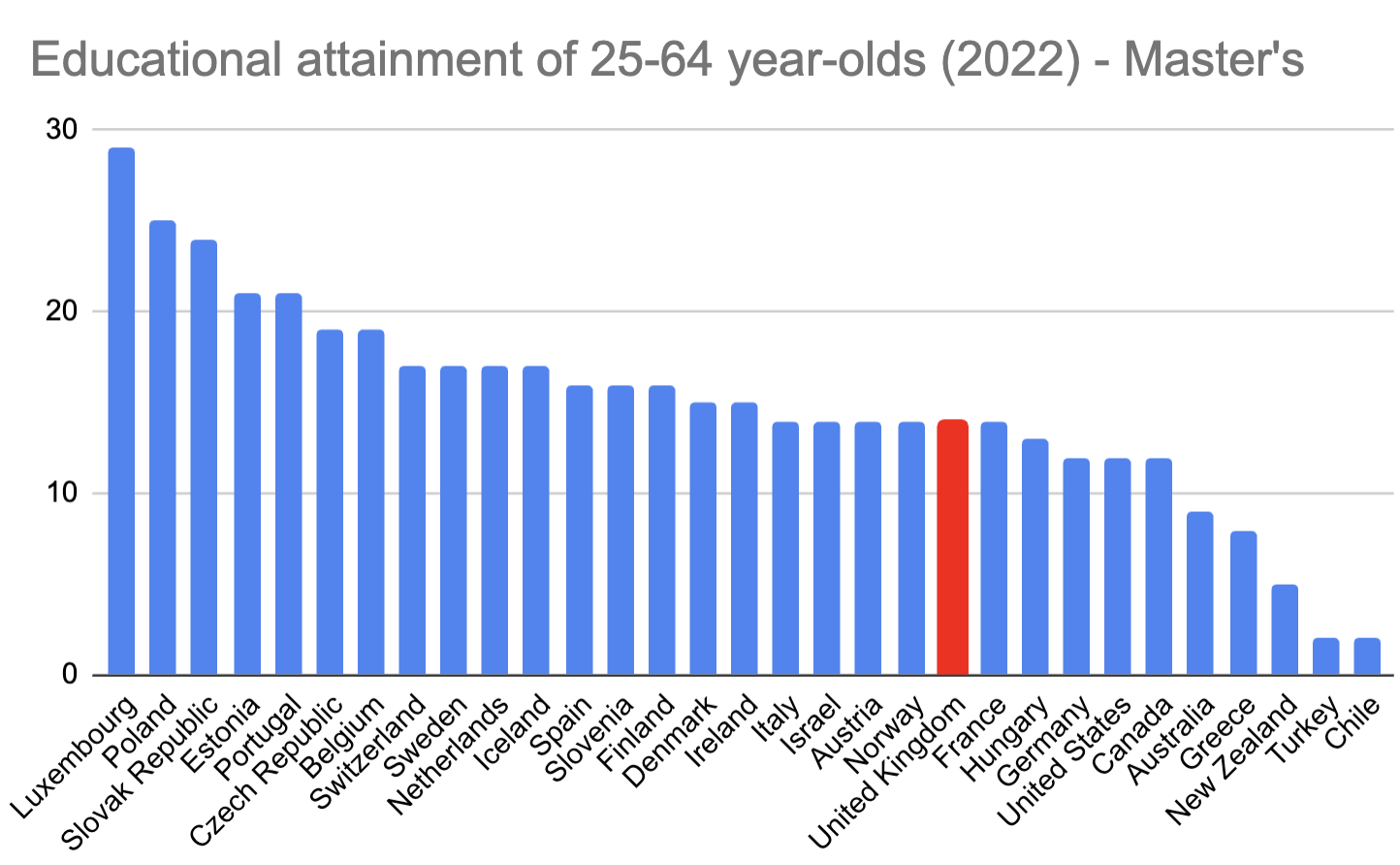

Even if we just take highest qualification in the population, in 2022, across the OECD, the UK was languishing near the bottom – and it’s doubtful that that’s about a lack of ambition:

Full-time is fine

But this all goes beyond funding. To the extent to which student diversity – in characteristics or in provision terms – is recognised, it tends to be “outside” of the full-time student assumption.

Hence the LLE is positioned as enabling adults to obtain new qualifications at a time that is right for them, and to train, retrain and refresh their skills flexibly throughout their lives.

But with changes to maintenance and the ability to obtain credit more flexibility, it could also enable what we think of now as “full-time” undergraduates to experience set backs, take a little longer, accrue credit between subjects and institutions, and obtain it for service, or work experience, or the application of knowledge to the community.

To the extent to which student diversity – in disability terms – is recognised, the only mentions are in relation to mental health (support) and the Disabled Student Commitment.

But with getting on for 40 per cent of the student body now in these categories, there is only so much bodging and “extra time for assessment” that can be done to enable their success in the system.

To the extent to which community is recognised, it tends to be in reference to something outside of the university, something to be partnered with. But one of the things we want students to be able to do as citizens is understand and recognise others’ needs – and make the decisions later in their lives to make the communities they inhabit better.

And across Europe, the recognition that students should have a more active say in decisions that affect them, minimum access to campus space, the right to safety, access to support when something goes wrong, support to foster campus communities, the ability to impact the curriculum and the right to more flexible curricula all suggest that the UK still has some way to go in imagining a blueprint for the student experience.

Even on the two issues that come up in the generational surveys – climate change and artificial intelligence – the blueprint seems silent on what students might want from their experience. The former suggests institutional change, the latter points at curriculum change, and both suggest efficiencies that point away from full-time study.

But there’s no evidence that young people want to speed up their entry to a hostile labour market – and plenty of evidence that they’d like to slow down, integrating their education into changing a world that they know should be better.

The truth is that UK HE has backed itself into a corner where it does too much for students – both in relation to the funding available, and generally. And without a vision for what students will do – individually and collectively – the problem will only get worse.

When the students’ union at Helsinki University describes their role, you can see the calls for funding and better buses that we might see here. But you can also see a vision – for the role that it wants students to be able to play both in education and wider society, both now and in the future:

- Our goal is to achieve equality in society. We promote accessibility of education, sufficient subsistence for students and free public transport. We want to live in a world where everyone is treated equally regardless of their background.

- We believe that education has the power to change the world. Education is more than mere book learning – it includes broad-mindedness and the ability to apply your knowledge. Our aim is that students could accumulate these skills both on lectures and by participating in the activities of the University community and society.

- We students must feel well to be able to build a fairer world now and in the future. To be happy during our studies, we need good healthcare services, comfortable housing, humane study requirements and meaningful leisure opportunities.

- We think that Finland should use at least 0.7% of its gross national product to development cooperation as per the UN’s recommendations. We must actively promote environmental responsibility, set an example by our own actions and take a stand on environmental issues at the University, in the city and in society.

- We dare to actively participate in public discussion concerning students and fearlessly take action against any flaws we observe. We are resolutely building the society of our dreams and offer our members opportunities to influence matters. The world must be changed.

It’s the sort of vision that we hear endlessly in graduation speeches. But it’s also the sort of vision that is absent in the UUK blueprint as published.

Building on futures

It would be unfair, perhaps, to expect that a Universities UK blueprint should have factored all of this in.

It is a contribution from those that run universities, that otherwise thoughtfully sets out some of the conditions required from government and work required by universities to enable the sector to succeed.

But government policy has not kept pace with the ways that student needs and expectations have changed, it has not kept pace with the ways in which the relationship between students and their university has changed, and nor has it kept pace with the ways in which the relationship between students and students has changed.

Thinking beyond fees or consumer rights need not necessitate the kind of nostalgia associated with public discussion of the student experience. 2022’s Student Futures Commission – in the teeth of pandemic recovery – was a good start. The government must now take the steps to enable students to build on it – because universities have no future without them.