Much of the supporting commentary around the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill and academic freedom goes like this.

Academics who wish to exert their academic freedom to research, produce knowledge, question beliefs, and pursue their interests are faced with “the uncompromising attitude of students.”

Students who seek similar autonomy in their learning through shaping their curriculum and reading lists, however, are undergoing “radicalisation”.

This mutually exclusive framing loses the importance of students as partners in pedagogy and erases the students’ academic freedom.

In all the discussion on academic freedom, the idea that students have a right to academic freedom has not been given much – or any – attention.

I recently asked a question about students’ rights at an event on academic freedom but was met with a tangential answer that pivoted back to the rights of academics.

I don’t at all think the question was being deliberately avoided – it likely wasn’t addressed fully because this is a novel idea in the free speech debate.

Even those who claim to valiantly defend free speech and academic freedom for staff seem to be in favour of squashing the academic freedom of students.

Thinkers on academic freedom and the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill with whom I have agreed in the past tend to perceive the authority of the educator – and the dutiful receptiveness of the student – as a given.

[the bill] could be defended very plausibly on the basis that it is up to universities, not students, to dictate what they teach and who teaches it, and that we need to protect that right.

This is hardly a ringing endorsement of academic freedom.

And it is also diametrically opposed to contemporary understandings of good pedagogy, the underpinnings of students’ belonging and the consequentially enriched learning environment.

Foundational freedom

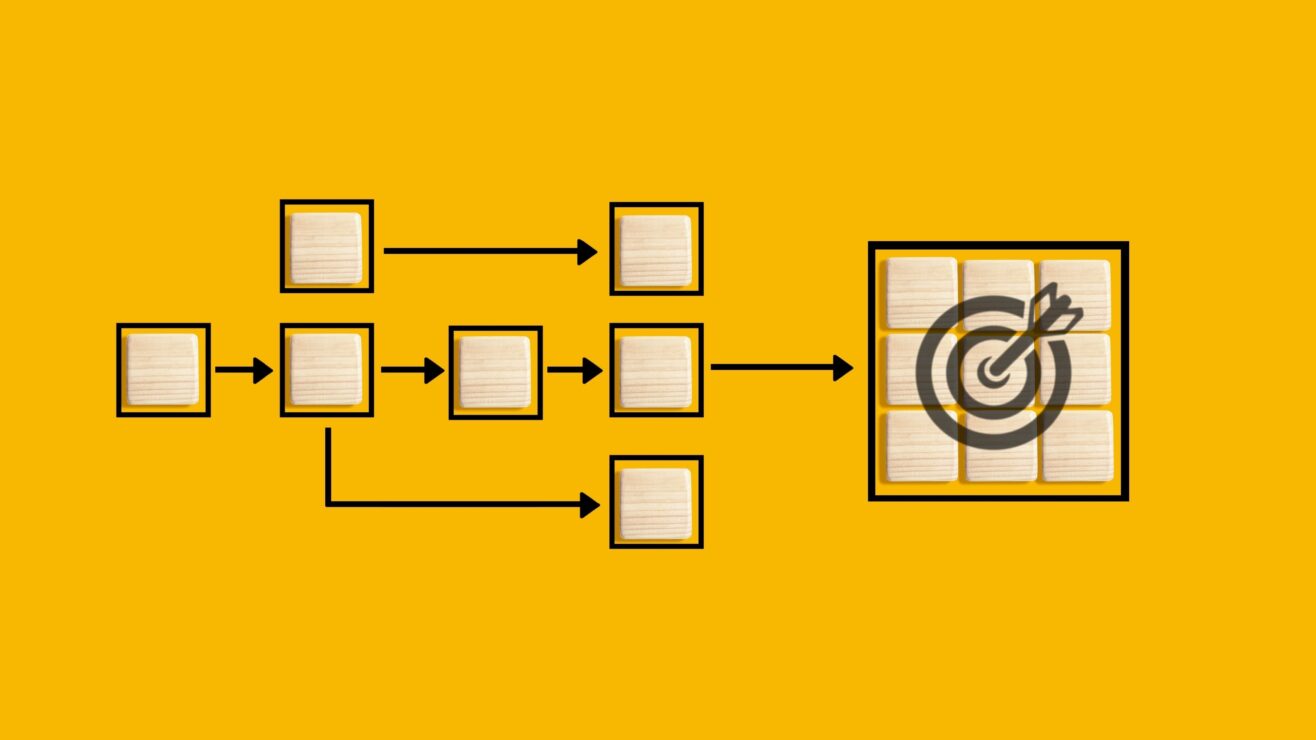

In the Wonkhe/Pearson belonging research – conducted throughout 2022 with over 5,000 student participants – students’ autonomy and academic freedom emerged so often as a theme that it became one of the four foundational pillars of our student belonging model. We found that when students are given academic freedom – to influence what they learn within the bounds of a subject framework – they develop better as scholars in their own right:

Our lecturers tell us they want to expand our interests but not limit it, so the projects or assignments they give us are very broad […] If they assigned something specific, I think it will feel like we are just trying to complete the assignment for the sake of passing the grades and not wholly for ourselves to grow.

When they are not, academic outcomes are at risk as their confidence decreases:

I felt my ability had been dampened by a lack of interest for my ideas and theories.

And it is not just students’ individual learning journeys that benefit, When students are seen as academic partners – rather than vessels into which information is poured – it enriches the curriculum, the learning experience for other students, and the academy as a whole.

Our student participants noted the symbiotic benefits when they are coproducers of knowledge and their input valued:

Our assignments are flexible enough to allow us the freedom to write what we are interested in within the structure. As a person with a living experience of mental illness, my input is valued and adds to the whole course understanding. I am equally learning and understanding from those who work in the mental health field.

Our professor would slightly change the way they would approach a subject to include those students’ understanding of it and may ask the student to contribute to the lecture. I always thought that was so … it was really thoughtful and gave you the opportunity of being on the other side of the classroom […] allowing each student to use what they already know.

… although [lecturers] have more knowledge, obviously, on what they’re teaching, sometimes we can bring them new ideas on modern problems.

Keep the classics, invite critique

Contrary to criticism, such student contribution does not erase core content but enriches it. The students we surveyed retained a respect for the core curriculum while articulating the positive benefits of including diverse content:

I believe that for students who come from [diverse] backgrounds or experiences, this inclusivity can spark creativity and engagement [although] we still recognise that anyone can be a valuable and worthwhile contributor to their field.

But when students are invited to participate in contributing to and shaping their curriculum, we have to be prepared not just for them to enrich it, but to critique it also.

This includes welcoming challenging discussions around the nature of the existing canon, students’ new non-Western perspectives, their suggestions to changes to reading lists, and revising traditionally held epistemological beliefs.

If you support academic freedom but do not support the freedom for students to contribute to or question their own syllabus – including in new intellectual directions – then you are fetishising the idea of academic freedom without dealing with its consequences.

I understand that they are the experts but isn’t it important for us as students to question the syllabus and topics we study?

The course programme is designed to be objective […but] professors, on the other hand, can sometimes bring their culture into the classroom. One of the lecturers is always giving real-world examples that are dominated by issues from a specific country […] Their unwillingness to be inclusive […] limit[s] them.

For the self-appointment champions of heterodoxy who criticise the “woke snowflake students” who critique their curriculum as afraid of challenge – surely, inviting their critiques and criticisms into consideration would surely be fitting with the free exchange of ideas.

The problem is not students asserting their academic freedom. The problem is when commentators frame the concept of students as co-creators as “activism” and “radicalisation” rather than what it is – evidence-led pedagogy – because the curriculum content differs from their own political agenda.

Such concerns around changing course content, which has always been in flux, are red herrings. Academic freedom is not what the student is being taught, it is how they are being taught.

The crux of the argument is that we should teach students in a way that is proven to enhance their learning, outcomes, curriculum, knowledge production, and the academy as a whole.

To do the opposite would be to go against both pedagogical good practice and academic freedom.

Diversity (of) fought

In the belonging research, the students’ desire to contribute to their curriculum didn’t tally with any group of students’ political leanings. There were students of all persuasions who appreciated how much academic freedom they were given in their modules. There were students of all persuasions who expressed dissatisfaction with how little academic freedom they were given in their modules.

My theory is that the reason de-westernised or decolonised curriculums are an emerging theme is not because of political agendas of, or pandering by, institutions to “diversity” but because in an expanding, diversifying, and internationalising sector, we welcome more diverse students. Of course, academics can expect these students to express a global range of perspectives, opinions, experiences, and cultures.

I’ve seen international students comfortable to share their perspectives on specific issues. The variety of readings reinforces a feeling of confidence to share different views, because we’ve already been reading so many different opinions.

And keeping with good pedagogy, these students must be active participants in their learning and we must allow them the freedom of speech to comment on – and criticise – their own curriculum:

The course did predominantly focus on white Europeans and often viewed peoples of colour through the Europeans’ lenses rather than as agents of their own history. However, I also felt I was in an environment where I wouldn’t be stifled from addressing this.

Curriculums are not following a political direction, they are following a pedagogical one.

Whether it is decolonisation, LGBTQ representation, or whatever topic it is that is riling up the tabloid commentators this week – the content is the result of a diverse student body exerting their academic freedom through evidence-led pedagogy. We must fiercely defend their right to it.

Did someone ask chatbotGPT to write a Guardian editorial?

Great write up, Sunday. It seems to me that proponents of “Free Speech” are always mistaken about what that entails. Free speech does not equal freedom from consequences, one of which can (and will often) be more free speech in opposition to the ideas originally purported.

Students are just as entitled to question and challenge their curriculum as lecturers are to deliver it. Anyone who says differently doesn’t care about free speech, they care about power dynamics.

I agree that students should enjoy academic freedom and freedom of speech within the law. They should be encouraged to question and explore. That can include inviting discussion on the canon – the best ideas and knowledge around. But the article conflates academic freedom with the intellectual authority of the teacher. Academics are charged with designing the curriculum based on the fact they have assimilated the field of study and engaged in a high level of scholarship. Students are starting out on that journey. To assert the student’s role as being akin to that of the lecturer regarding the curriculum… Read more »

The arrogantly convinced versus the unknowingly untutored.