Universities should consider students’ spelling, punctuation and grammar when marking exams and assessments, the Office for Students (OfS) argues in a new report.

Assessment practices in English higher education providers: Spelling, punctuation and grammar considers approaches to assessment at a number of universities which have policies where proficiency in written English is often not assessed, and concludes that the issue may be widespread.

In deciding their approach to assessment, universities involved in OfS’s review often pointed to a desire to achieve or promote inclusivity. The report sets out OfS’s view that all students should be assessed on spelling, punctuation and grammar in order to maintain quality and protect standards.

What’s that you say? What is this now? Where has this all come from? Cue the harp and the wavy fade.

April fools

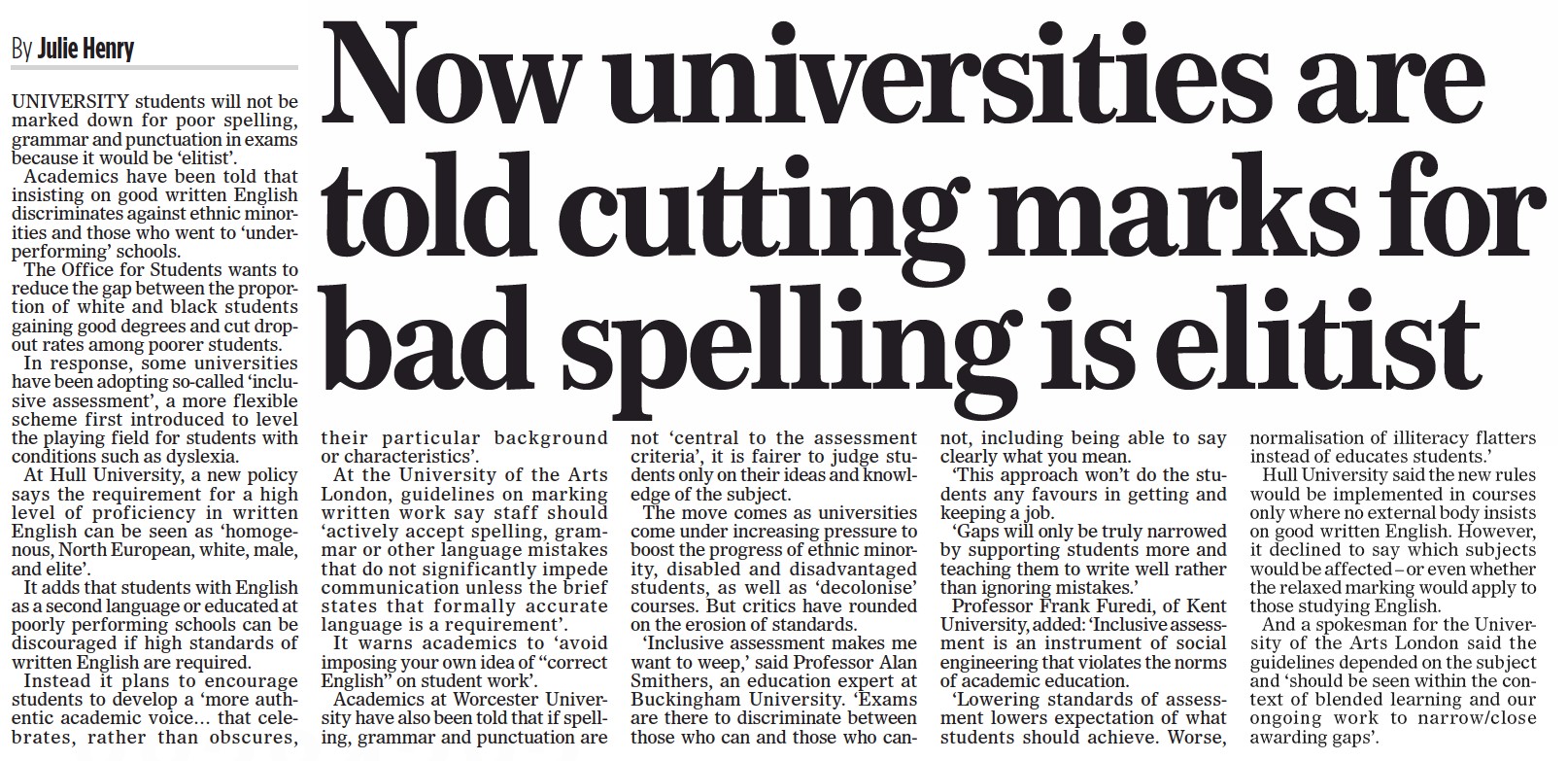

Cast your mind back to April 11th 2021. As its big “bash universities” story of the week, the print version of the Mail on Sunday treated its readers to the news that universities had been told that “cutting marks for bad spelling is elitist”.

The online version ramped up the rhetoric for clicks, shoehorning in the word “fury” and directly fingering the Office for Students (OfS) as the source of the edict:

Fury as education regulator tells universities that marking students down for bad spelling is ELITIST. Academics have been told that insisting on good written English discriminates against ethnic minorities and those who went to “underperforming” schools. The Office for Students wants to reduce the gap between the proportion of white and black students gaining good degrees and cut dropout rates among poorer students.

Alan Smithers and Frank Furedi both appear with quotes as the Statler and Waldorf of these types of stories – but there were other problems with it, one of which was the suggestion that OfS had made universities do it. Given the regulator had been busy mending its relationship with ministers – who by Sunday afternoon were being pressed for a quote condemning so-called “inclusive assessment” practices – by that evening the Mail had to amend its headline, and OfS had taken the unusual step of flatly denying the story via a statement from director for fair access and participation Chris Millward:

It is patronising to suggest that standards should be reduced for particular groups of students and the OfS has not called for – and nor do we back – policies like these. There is a very real issue in higher education with an unexplained gap in outcomes for some groups of students, including black students and those from disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Universities are looking at various ways of reducing these disparities but that should never result in a reduction in the academic rigour required for higher education courses.

Trouble is, that was all too late for the interns who rewrite other papers’ stories – and by the Thursday after a week of moral panic phone-ins and op-eds about the decline of standards (Eve Pollard had a view, etc), the issue was being raised on the floor of the commons, where universities minister Michelle Donelan said:

I am appalled by the decision of some universities to drop literacy standards in assessments. I think that this is misguided, and, in fact, it is dumbing down standards. That will never help disadvantaged students. Instead, the answer is to lift up standards and provide high quality education.”

To be fair to everyone concerned, that reaction shouldn’t have been a huge surprise. To the extent to which there is any government policy on standards, Michelle Donelan was pretty clear in her July 2020 NEON speech when she said:

And too many universities have felt pressured to dumb down – either when admitting students, or in the standards of their courses. We have seen this with grade inflation and it has to stop. We need to end the system of arbitrary targets that are not focused on the individual student’s needs and goals. And let’s be clear – we help disadvantaged students by driving up standards, not by levelling down.”

Who knows what went on behind the scenes – but what we do know is that by June 23rd, England’s independent higher education regulator had felt the need to interrupt a long form review of its definitions of quality and standards to run a mini review of a particular aspect of quality and standards triggered by a Mail on Sunday article:

The Office for Students (OfS) has today launched a review of the use of ‘inclusive’ assessment practices that disregard poor spelling, punctuation and grammar when students’ work is assessed. The review is part of a range of activities to drive up the quality of higher education courses and ensure that standards are maintained.

And that’s what has appeared today.

Proficiency test

Given the context and the Millward quote, the contents shouldn’t be a particular surprise. Via a review of policies and practices in a “small number” of higher education providers, it concludes that:

- Some providers’ assessment policies are designed in a way that means spelling, punctuation and grammar are not assessed.

- Some providers’ interpretation of the Equality Act 2010 and other relevant legislation has led to their not assessing technical proficiency in written English for all students. OfS does not consider that approach to be necessary or justified.

- Providers should assess spelling, punctuation and grammar where this is relevant to the course, subject to compliance with their obligations under the Equality Act 2010 and other legislation. OfS would expect this to mean that most students on most courses should be assessed on their technical proficiency in written English.

- OfS says there is no inconsistency in a provider complying with equality legislation and making its assessments accessible, while also maintaining rigour in spelling, punctuation and grammar – and says that providers should ensure that students benefit from both accessibility and rigour.

To reach these conclusions, we discover in the penultimate paragraph that the evidence for the review was collected by the designated quality body for England (that’s the Quality Assurance Agency to you and me) and that a “small, targeted group of providers” gave the review team access to information like policy documents and even examples of assessed student work.

From that, OfS manages to argue that:

The common features we have seen in the small number of cases we have considered in this review suggest that the practices and approaches we have set out in the case studies may be widespread across the sector. We are therefore drawing the attention of all registered providers to our findings, because they highlight matters that are likely to raise compliance concerns, now and in the future.

As you’d expect, the issues are linked back to OfS’ regulatory framework. For condition B1 (“The provider must deliver well designed courses that provide a high-quality academic experience for all students and enable a student’s achievement to be reliably assessed”) it says:

We take the view that, for a course to be well designed and provide a high-quality academic experience, it should ensure that students are required to develop and demonstrate subject-specific and general skills. These will include technical proficiency in written English in most cases. For students to demonstrate such skills, they need to be assessed and such assessment must be reliable. It is unlikely to be possible to reliably assess student achievement if proficiency in written English is not included in intended learning outcomes.

And for B4 (“The provider must ensure that qualifications awarded to students hold their value at the point of qualification and over time, in line with sector-recognised standards”) it says:

We take the view that, if students are able to achieve qualifications with poor written English because it is not assessed, those qualifications are unlikely to have the value taxpayers and employers would expect.”

There’s also a long section on disabled students (support them to achieve, don’t lower the standards), clues as to which bits of a revised framework would kick in if its proposals on quality and standards survive (B1, B2, B4 and B5), some speculation that the issue might have caused grade inflation (a hypothesis it says it will test for individual providers through its investigatory work) and one of those “you have a year” warnings:

We recognise that some providers may need time to review and revise their approaches to the assessment of technical proficiency in written English. We will revisit this issue in a year’s time. From October 2022, we would expect to take action where we find assessment practices that lack rigour in the ways identified in this report.

I got my rock moves

There’s lots that could be said about the report and some of the wider implications – one way we can read the document is as a(nother) swipe at the QAA, insofar as the case studies in the report suggest that some providers were only testing proficiency in written English if doing so was etched into a specific subject’s benchmark.

The narrative itself inevitably avoids discussing the Quality Code or subject benchmarks, but the logical conclusion on the latter is a unilateral rewrite of all of them that includes a line like the one in the Subject Benchmark Statement for English:

Exhibit an effective command of written English together with a wide-ranging and accurate vocabulary”

The nations will complain about the imposition, but they’ll also want to avoid the row in their section of the press too. And there end up being questions that go down even to the module level, given that throughout the case studies in the report OfS notes things like policies where “technical proficiency in written English is not assessed unless it is a learning outcome for a module or course”.

But more broadly, you can see the document as telling us interesting things about who sets OfS’ agenda and its supposed independence.

We are told elsewhere that OfS isn’t exactly flush for cash or short of demands to respond to, yet has picked this up – and so even if OfS was to argue “well a serious issue was drawn to our attention”, given it has abolished the “random sampling” of providers it would appear that “what the Mail on Sunday gets upset about” has now become a formal part of its regulatory risk prioritisation framework, which (charitably) may well end up distorting its priorities a little.

It also reinforces the idea that its nods to student voice are tokenistic. Not only is there little evidence that students would highlight this issue for action (and there are plenty of others they would prioritise), the student voice in the report itself is eerily silent. Ask any group of course reps about this agenda (and I have) and you’ll find concern about effective English language support for international students and those that have tended to be recruited on potential rather than raw attainment – aspects not mentioned here. It’s almost as if OfS obsesses over judgement at the expense of a focus on support – in more ways than one.

There will also be some that argue that OfS is encroaching on sector / institutional autonomy here. But for all its subject diversity and inclusion of vocational subjects and curricula, the idea that higher education doesn’t universally test a basic standard of students’ written English is a complete anathema to what higher education “is” in the popular consciousness.

As such, even if an inclusive assessment policy of the sort identified here was well intentioned and reasoned (and was more thoughtful, for example, about exactly “why” we would test written English proficiency in students with Specific Learning Difficulties studying something heavily vocational), it wouldn’t be the hill I’d die on if I was a vice chancellor.

The “you have a year” warning is particularly interesting too: it would be very difficult for the OFS to intervene in this matter under the current regulatory framework, however it would be much easier under the proposals for B4 and B5 which were recently consulted on. You could therefore take from their October 2022 timeline that the consultation outcomes have been set just a matter of days after the consultation closed. One can only assume the sector was in vigorous agreement with the proposals! *please excuse any grammatical or spelling errors: I didn’t do English at University.

What really struck me about the ‘report’ was the paucity of the evidence base and the sheer amount of speculation (mays, mights and coulds) underpinning its conclusions. Beautifully spelled it may be, but credible research it is not. Still, priorities, eh.

My second thought was ‘shouldn’t schools be getting people to an acceptable standard of spelling and grammar before they even get to university’ – you know, those schools which the government has been telling how to teach spelling and grammar for the past decade.

If it isn’t taught can it be a legitimate learning outcome – are we all to become English teachers?

Agree wholeheartedly with all of this response, but what really irritates me is the lack of understanding and clarity behind what is being proposed. As Sarah points out, their report is so full of holes and so poorly justified, it would be unlikely to reach an UG pass mark despite being correctly spelled. The reason why spelling, punctuation and grammar are important according to the report is because “Wherever a discipline requires analysis, effective communication is critical if students are to demonstrate an ability to engage with and convey complex arguments. This cannot be done without technically proficient use of… Read more »

Spellchecker. Grammarly. They should get most of our students mostly language error-free, at least in coursework. Or is using them cheating? Like hiring a professional copy-editor? Let’s prepare students to function well in the real world, with the technologies available. Anyway, the final responsibility for the work – quality, clarity, spelling, grammar and all – still lies with the author.