Fee cuts and funding changes? It’s the politics, stupid.

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

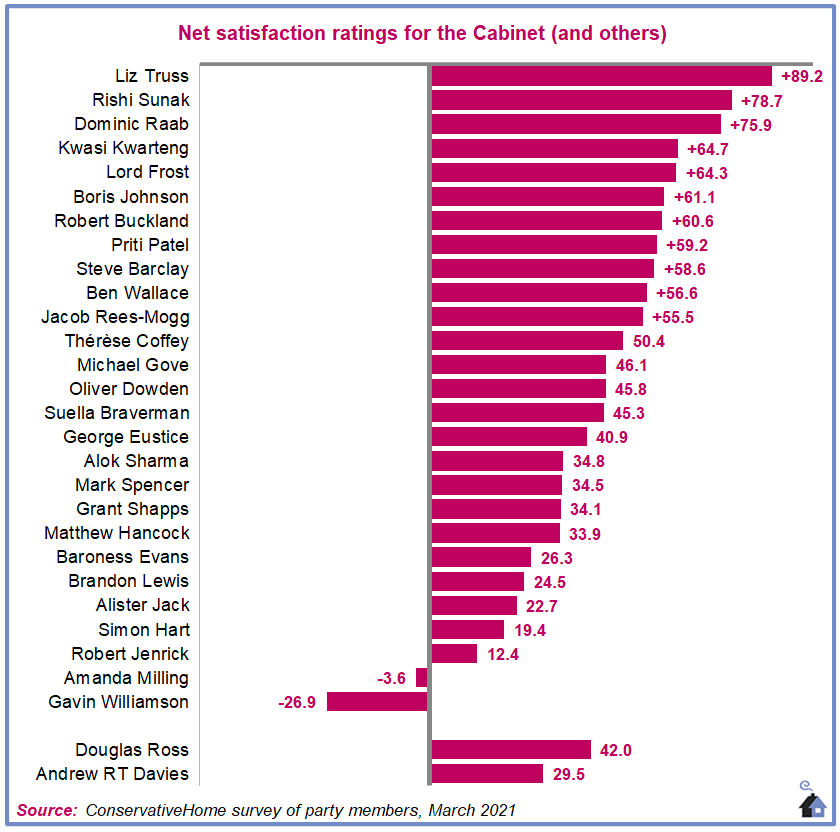

The Times story effectively builds on a Conservative Home blog from the Secretary of State (“Skills, jobs and freedom. My priorities for this week’s Queen’s Speech and the year ahead”) that presumably is designed in part to try to shift his stubbornly poor net satisfaction ratings amongst members – which as of March 2021 were stuck at an impressive -27 points.

The culture wars stuff both in the new Bill and the blog is a fairly naked attempt to cheer up the conservative clubs and the backbenches. It matters not that it doesn’t seem to be underpinned by evidence or logic or a reliable theory of change – it’s just that “we will put an end once and for all to the chilling effect of cancel culture in universities” sounds right.

The catnip line on courses in the blog is as follows:

The record number of people taking up science and engineering demonstrates that many are already starting to pivot away from dead-end courses that leave young people with nothing but debt”

Elsewhere on the site David Kernohan reminds us why government using finance to determine what people should be studying at university is a bad idea in general and how difficult the real hunt for a “low value” (or this time around, “dead-end”) course tends to be if you do so in good faith.

The story claims that a consultation on cutting tuition fees will be launched by DfE in June. This shouldn’t come as much of a surprise – in the interim response to the Augar review that we got in January, we were told:

We plan to consult on further reforms to the higher education system in spring 2021 including student finance terms and conditions, minimum entry requirements to higher education institutions, the treatment of foundation years and other matters”.

Inevitably eyes and ire drift towards fees, the overall unit of resource and the potential use of minimum entry criteria to gain access to the student finance system – and whether the days of foundation years are numbered. But it’s the bear. We should always look out for the bear.

The other notable line in the blog on the Skills Bill was that government would “strengthen the ability of the Office for Students to crack down on low-quality courses”, which was also in the Queen’s Speech briefing earlier in the week.

In the OfS quality and standards consultation, there was much material on constructing outcomes baselines at subject level – and also a debate on whether to split out partnership provision and TNE.

Within the terms of the debate about minimum outcomes, that kind of move is fair enough. As we’ve covered on the site before, in large providers you can easily end up with many thousands of students studying subjects whose outcomes are below the thresholds for continuation or graduate jobs if you just look at institutional aggregate figures.

But the thing about the OfS consultation is that while it was clear on options for whether and how to judge “pockets”, it was vague on what it might do if it spotted one. That’s because its regulatory tools relate to providers. It doesn’t appear to be within its powers, for example, to restrict access to the loan book at subject level.

And from DfE’s point of view, the threat of deregistering the whole provider over a poor performing subject area puts at some risk the infrastructure you need to deliver your wider, more flexible and bitesize skills agenda – and your levelling up plans.

The key here is page three of Williamson’s letter to OfS in February, and specifically the bit on quality where he says:

OfS should not hesitate to use the full range of its powers and sanctions where quality of provision is not high enough: the OfS should not limit itself to putting in place conditions of registration requiring improvement plans for providers who do not demonstrate high quality and robust outcomes, but should move immediately to more robust measures, including monetary penalties the revocation of degree awarding powers in subjects of concern, suspending aspects of a provider’s registration or, ultimately, deregistration”

It’s never been clear that OfS actually has intervention powers that could be deployed that rapidly, or at subject level. So it looks fairly clear that as part of its work on quality and standards, OfS has said to DfE “thanks for the letter, but you’d need to beef up our powers”.

So what you end up with here is a sort of four-pronged squeeze, with each step scarier than the last:

- First, the main thrust of the levelling up stuff – lots of making more local, shorter and cheaper technical provision easier to run and put on.

- Next, some minimum entry criteria – highly likely to be contextualised in some way, but nevertheless criteria that would give access to the loan system (sold as it was in FE in the 90s and 00s on “the right pathways for their abilities” and so on).

- Then there’s the headline Augar funding changes that would reduce “debt” and hide some changes to the loan repayment scheme to tip the cost back towards graduates following Theresa May’s raising of the repayment thresholds – and would and reduce funding for humanities, arts, etc – where the “strategic priorities fund” debate has basically been a rehearsal.

- And then the scariest stuff of all – an attempt to chop out pockets of “poor outcomes” provision at entire subject level, mainly from former polytechnics and the dodgier “above a kebab shop” challenger providers. That will mirror what happened in FE in the 90s and 00s (try doing an A Level in a GFE college these days) and will be a nuclear version of recent debates over course closures.

The Times headline is “university fees to fall – but arts degrees may suffer”. As we’ve said before, it’s easy to miss something you’re not looking for.

The big gamble here is that across the Conservatives’ new electoral coalition, there’s something for everyone – for the shires’ Blue seats in the south where the young fly the nest for university, there’s a headline fee/debt cut – and for the red wall there’s jobs, apprenticeships, skills and “no need to leave home”. Whether that is morally and economically wise or stacks up statistically in any meaningful sense may not matter.