Back in April on the podcast, we were wondering whether the character of regulation of universities in England was right for the emerging context – whether competition and markets and “you have to solve the problems yourself” would really cut it in the emerging world.

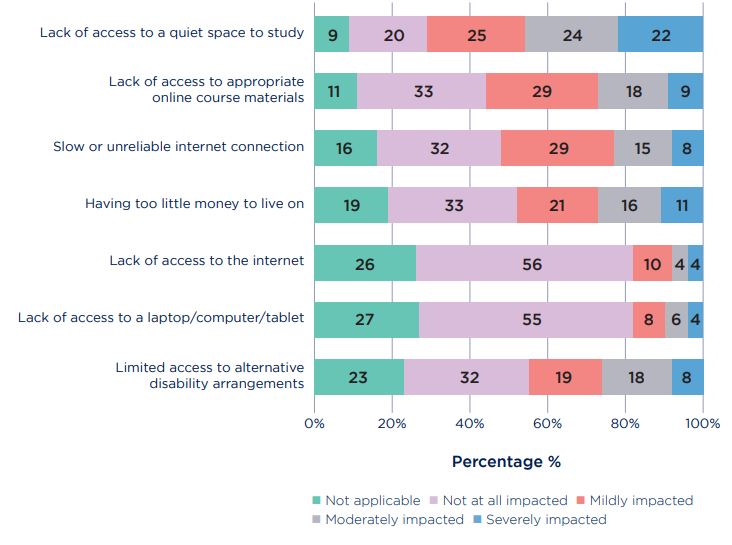

Meanwhile, students were trying to study. We now know that 71 per cent of students say they lacked access to a quiet study space, with 22 per cent “severely” impacted.

56 per cent said they lacked access to appropriate online course materials, with almost 1 in 10 “severely” impacted. 1 in 5 say they were impacted by lack of access to a computer, laptop or tablet.

And over 10 per cent said they were severely impacted by having too little money to live on.

I’m after a favour

In June, Gavin Williamson wrote to outgoing OfS Chair Michael Barber asking him to do two things.

The first was “to consider how providers could continue to enhance the quality of their online delivery for the approaching academic year” so that “claims of quality can be made with confidence”. The second was to consider what “longer term opportunities” there might be for the sector to “develop and innovate in relation to the provision of digital and online teaching and learning”. In Scotland, they announce cash. In England, they announce taskforces.

Now OfS has launched the work by publishing polling on students’ experiences of online learning and the “digital divide” since the onset of Covid-19, and fleshing out how the review(s) will work.

First up we get something approaching a useful definition of ”digital poverty” – which OfS defines as a student being without access to one of the core items of digital infrastructure: appropriate hardware, appropriate software, reliable access to the internet, technical support and repair when required, a trained teacher or instructor, and an appropriate study space. That’s a handy paragraph to insert into bursary criteria policies.

It’s not really in OfS’ gift to do so, but sadly there’s no money in today’s press release to help providers bridge that digital divide. In fact oddly, beyond that bit of text, there’s not much in today’s press release about current students at all. Let me explain.

Getting better every day

You may remember that moment back in June when the Higher Education Policy Institute suggested that this year’s Student Academic Experience Survey showed that during the crisis, students’ perceptions of some elements of their teaching had actually improved.

The claim was based on differences between the results gathered before and after lockdown began, but a glance at the sector’s term dates and the survey fieldwork dates, plus the questions actually asked, suggested that claim was… optimistic. And once DK had looked at the characteristics of the students represented in pre and post, we were fairly confident that while we might have been in correlation land, we almost certainly hadn’t booked into causation hotel.

To be fair to HEPI it did later publish polling on student satisfaction and communication during lockdown that wasn’t so positive, but generally you have to be careful with claims like the SAES one – because they take on a life of their own. Michelle Donelan spent much of the May and June telling students they wouldn’t be entitled to a refund “if the quality is there”, and so seized on the HEPI claim on its webinar, where she said:

I really was pleased to read HEPI’s survey which highlighted that many providers have been pretty successful in meeting their students’ academic needs – students felt that overall [during the lockdown] their academic experience was better than expected, and the contact I actually increased – they were also doing more assignments, getting more feedback and felt more supported in their independent study. This is quite frankly tremendous feedback, and was partly achieved by making the most of educational technology – and I do think this sets us up well for the future”

This didn’t seem to chime with feedback that SUs were getting, both anecdotally or as part of our research with SUs and Pearson, which surveyed nearly 3,500 current students on their expectations and experiences. But you’ll recall that we’d heard in May that OfS was doing some “student polling” of its own to find out what students were thinking – and now we can see some of its results.

Absolute clarity

What has happened here is that OfS has essentially taken the advice it gave to providers in April and boiled it down into short sentences, which act as a neat summary of what, in its view, students had the right to during lockdown. (I’ve written before at how frustrating it is that OfS doesn’t communicate that kind of simplicity to students so that “empowered consumers” know what they should be expecting).

It then asked student research firm Natives to work out whether students agreed that this was what they were experiencing, alongside asking about aspects of access and we are now calling the “digital divide”.

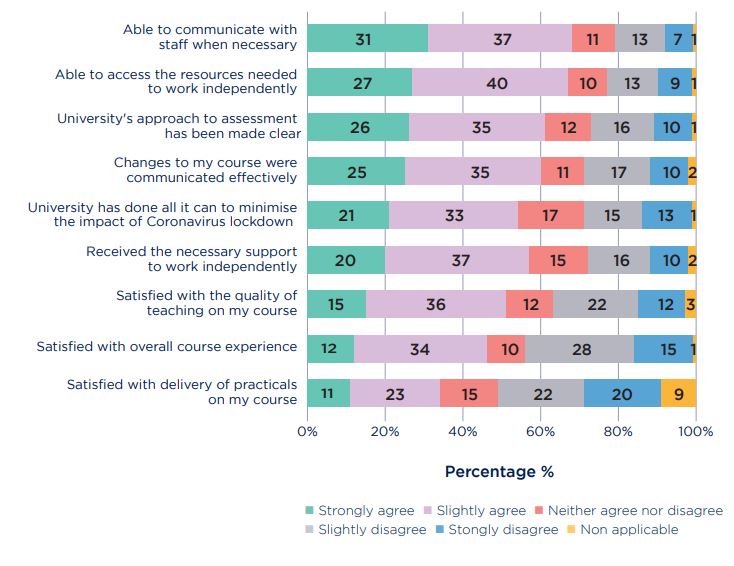

It’s not great news. Able to communicate with staff when necessary? 1 in 5 disagreed. Able to access the resources needed to work independently? Almost a quarter disagreed. University’s approach to assessment clear? Over a quarter said “no”. Similar numbers for “changes to my course were communicated effectively”.

University has done all it can to minimise the impact of lockdown? Received the necessary support to work independently? Best part of 30 per cent disagreed. Satisfied with the quality of teaching on my course? A third disagreed. Satisfied with overall course experience? Just under half disagreed. Satisfied with delivery of practicals? Ditto.

Now you may be thinking “well Jim, there was [and indeed still is] a pandemic on”, and of course you’d be right. OfS says that it should not be forgotten that providers were transitioning to digital teaching at a time of immense pressure and unprecedented emergency – its regulation during the period reflected this “in its risk-based approach”.

I’m certainly not necessarily suggesting that it would have been generally possible to improve on those scores given the circumstances. But from students’ perspective, the messaging from ministers, UUK et al at the time wasn’t “yep, it’s poor, but there’s a pandemic” – it was “it’s all fine, great even, it’s just that it’s online now”. There were, after all, calls for refunds to rebut.

OfS says the polling provides a “useful national snapshot” of students’ experiences in relation to the support they received during lockdown, teaching, and their digital experiences – there aren’t enough responses to support any conclusions about the practices of individual providers.

It also says the data will help “inform its ongoing approach”, particularly regarding quality as we enter a new academic year. And its digital teaching and learning review will help both OfS and the sector “learn more about what success in digital education looks like”. Being able to access it would be a start I think.

No overnight miracles

It has now been some time since enforced, emergency lockdown. But the level of chaos hasn’t changed much, plenty of providers instituted recruitment freezes or even redundancy programmes, and the level of investment in staff development or tech to ensure “claims of quality can be made with confidence” hasn’t really been there.

Similarly, the “digital poverty” issues haven’t disappeared over the summer – in fact in many universities they’ve been exacerbated. The way that students without things on the list of “core items of digital infrastructure” overcome that is by using shared campus infrastructure, that is now a) heavily Covid restricted and b) under even more pressure in some providers thanks to the places crisis.

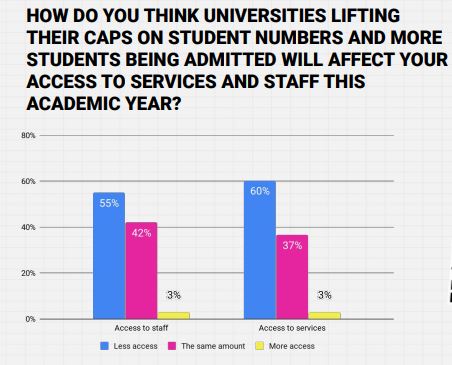

As such it’s been fairly galling to see OfS pressuring providers to ensure everyone gets a place without reminding them of the need to ensure that the wider human and physical infrastructure can support them – particularly when the polling firm that OfS uses this week told us that students think this:

In other words, as we head into September, 71 per cent of students will still lack access to a quiet study space.

What should happen

In the circumstances there are some things that a national regulator could be doing. For example, it could announce that it will investigate what led to such significant dissatisfaction and poor compliance with what should have been, in its official view, universal student rights. It could announce that given the findings, it will step up efforts to encourage students who felt let down to launch a complaint – so they can obtain redress.

Having reassured the Chair of the Commons Education Committee that it was monitoring both these issues and students’ access to learning, it could update Robert Halfon on these results, revealing some of the rest of the polling – demonstrating the large percentages of students impacted by a lack of access to a quiet space to study, a lack of access to appropriate online course materials, slow or unreliable internet connections, having too little money to live on, a lack of access to the internet, a lack of access to a laptop/computer/tablet, or limited access to alternative disability arrangements. Such a letter would could out for the committee the specific actions OfS is taking to address the problems in relation to September. A similar letter would be sent to Gavin Williamson.

It could have secured agreement from the other funding bodies and ministers to ditch next year’s NSS and switched that capacity into something that would be much more meaningful – a national pre-arrival questionnaire with results by subject and provider to help universities prepare, and perhaps regular pulse surveys designed to help providers respond quickly to student problems this autumn, with funded rapid collaboration groups over specific issues like online isolation.

It could publish the detail on its analysis of comments on lockdown learning that were in the 2020 NSS, as it said it was doing in its last board papers. It could hold a meeting of its student panel – the first since February – to get some feedback on some of the issues from students who would know. It could insist that Michelle Donelan does not keep implying that the Student Premium Funding it distributes on DfE’s behalf is new money, and could warn the minister – who previously assumed that provider hardship funds would be able to cover the costs of many of the aspects of those access issues but evidently couldn’t – that she will need to put more money in.

And to tackle the issues in its polling, it could announce a series of steps for this coming September on checking on university outputs, rather than just waiting for outcomes – to ensure those access issues are tackled and to ensure that students are getting what has been sold to them. Crucially given it’s a regulator, it could go further than merely relying on complaints from students who don’t know their rights, a notifications process few know about, or checking on students’ outcomes in 18 months time.

But OfS has not announced the above – it’s not in its “character”. We get the polling, a reminder of the previous guidance, and some detail on the “longer term opportunities” request from Williamson, whilst not really addressing the “online delivery for the approaching academic year” request:

The polling provides a useful national snapshot of students’ experiences in relation to the support they received during lockdown, teaching, and their digital experiences – it does not support any conclusions about the practices of individual providers. Addressing student complaints and notifications is an important part of our monitoring work. Additionally, since the pandemic began we have been engaging regularly and closely with providers on a number of issues – including on quality of provision and the shift to digital teaching.

That longer term piece of work is due to report – the avalanche is coming, if you will – in March 2021. Hopefully, we’ll all be reading it in the waiting room for our dose of vaccine. What we can assume is that students on the wrong side of that digital divide can’t wait.