Should students get a refund? Some should, says a committee – but they won’t

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The government’s response to Covid-19 has inevitably been a major issue of concern to the public – and that has generated a bunch of parliamentary petitions, many of which concerned universities and the impact of Covid-19 on students.

The four big ones between them managed to generate a whopping half a million signatures, and there were several additional petitions specifically about international students outside of that total.

To respond, the House of Commons petitions committee launched an investigation into how students had been affected by the pandemic, as well as the UCU strikes that took place earlier this year. The committee received over 28,000 detailed responses from students, parents and university staff – with the committee expressing particular concern for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, and those on more “hands-on” courses where students need to use university facilities.

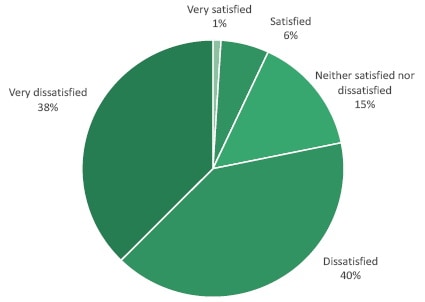

In a poll on The Student Room, only 7% of students were satisfied or very satisfied with the quality of the education they received during lockdown. The vast majority of students (78%) said they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. This, it says, compares unfavourably with 2019’s National Student Survey results – which effectively showed the reverse.

The good news for the government and Universities UK is that the committee rejects calls for a universal entitlement to tuition fee refunds, because at least in some cases students have “continued to receive an excellent education”. It’s everyone else that the committee is concerned for – and this is where things get confused in the committee’s report. In a long section on student rights and quality, the committee manages to completely misunderstand both consumer law and the role of the OIA.

On consumer law, the report asserts that students are entitled to their university “repeating part of the course” and a [partial] “refund, up to the full price of the course” if their university “fails to provide” the education they have paid for. That’s a garbled reference to two of the remedies available under the Consumer Rights Act 2015. But the committee misses the central defence of universities in this scenario – that their “Force Majeure” clauses in student contracts allowed them to vary delivery or not perform because of the pandemic.

The committee sensibly argues that the government should work with universities and the Office for Students to ensure that all students are advised of their consumer rights and are given clear guidance on how to avail themselves of these if they feel their university has failed to provide an adequate standard of education. But as we’ve noted before, no-one seems particularly interested in ensuring that individual students are aware of their rights, let alone being able to use them.

On quality, the committee picks up Universities Minister Michelle Donelan’s repeated assertions that there will be no refunds “if the quality is there”. But again the committee fails to notice that complaints about academic quality are usually outside of the purview of both university complaints procedures and the OIA – an issue we picked up here.

It fancifully suggests that complaints about quality should involve “an independent and objective assessment of the quality of education they have received over the academic year”, without realising that the entire basis of the UK system right now is that universities mark their own homework, and are going to give themselves good honours in this scenario.

To pay for the refunds that the committee thinks students will get thanks to its recommendations, it says the government should consider providing additional funding. There’s not a chance that government will do that – and given the quality assurances that government received from universities about what it was possible to do in April and May, it will in any event now blame them if it turns out those reassurances weren’t quite true.

Outside of this central runaround, the committee says that government should consider making additional funding available to students who might want to extend their education and to provide ongoing employment advice and support beyond graduation in what is likely to be an extremely challenging employment market.

But on its central recommendations, this appears to be another example of a lot of people with power conspiring to ensure that those with very little are prevented from using the little bit they do have. If a parliamentary committee can’t get its head around the legal issues, what chance do students have?