The annual data release published by the Higher Education Statistics Agency can usually be relied upon to show an uptick in the proportion of firsts awarded. This is accompanied by newspaper inches decrying the decline of academic standards in the UK and a reaction that points to the improvements in teaching and the motivation of contemporary students.

The latest release was no exception: in the last academic year, a quarter of graduates from UK universities were awarded a first-class degree.

Sending signals

However, there is a legitimate question for the sector to answer. The purpose of the honours degree classification is simple. It is a signal, used by universities to record the academic attainment of individual students, by graduates to indicate their academic achievement, by employers to identify the prospective employees and even by league tables to rank universities.

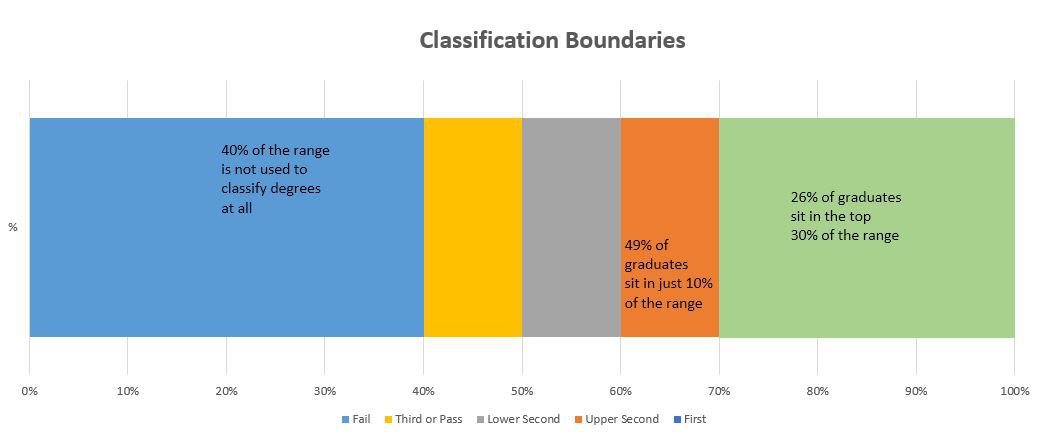

In this context, it is not hard to understand why the honours degree classification has come under sustained criticism in recent years. Graduate achievement is effectively recognised on a four-point scale, with almost three-quarters of graduates with classified degrees fitting into just two points of the scale. This presents a problem for a system that is meant to enable some degree of differentiation between students.

These limitations have long been recognised. In 2007, the Burgess Report concluded that “the UK honours degree is a robust and highly-valued qualification, but the honours degree classification system is no longer fit for purpose…” and that it “…does not do full justice to, the range of knowledge, skills, experience and attributes of a graduate in the 21st century.” The sector responded, trialling the Grade Point Average (GPA) and the Higher Education Achievement Report to attempt to give a more complete record of achievement. The success of these initiatives has been mixed. For example, as there is no single, sector-agreed scale the GPA may actually exacerbate existing problems.

Meeting the challenge

This presents two distinct challenges for the sector. The first is the extent to which recent trends in graduate attainment can be explained by grade improvement, rather than due to inflationary academic practices. This element dominates the public narrative and needs to be addressed to maintain confidence in the sector. But perhaps the more fundamental challenge is how classification responds to legitimate improvements in student attainment over the longer term, such as increased investment and improved teaching.

It is essential that the sector actively addresses these complex challenges to maintain confidence in academic standards and protect the value of a degree to students and employers. The UK Standing Committee for Quality Assessment (UKSCQA) is already acting to mitigate the risk of grade inflation in the UK higher education sector, overseeing a Higher Education Academy project on the external examination system as well as a recently completed project on degree algorithms, delivered by Universities UK and GuildHE.

Subsequent independent analysis based on the algorithms report further highlights the risk that the design of algorithms could undermine confidence in the fairness and consistency of degree outcomes.

The latest project will build on this work. Universities UK, together with GuildHE and the QAA will deliver work that will explain the extent to which trends can be explained by grade improvement, inflation or the changing profile of the sector itself.

We will clarify the grade classification boundaries in use across the sector and explore ways of managing risks of inflation and improvement in a distributed, diverse and autonomous system in the future. The UKSCQA will oversee the work offering a valuable UK-wide perspective into what is a UK-wide phenomenon.

This conversation about degree standards needs to ask challenging questions about academic practice and longer-term trends in relation to attainment. It also needs to be broad, recognising the sector’s growing diversity by bringing together different types of higher education provider, engage with students and student representative organisations and understand the needs and requirements of professional bodies and employers.

There will be no shortage of opportunities to participate in the conversation: if you are interested, please get in touch.

![william-hammonds[1]](https://wonkhe.com/wp-content/wonkhe-uploads/2018/01/william-hammonds1-430x430.png)

Second WonkHE article on this topic I’ve read this morning referring to independent analysis subsequent to the UUK:GuildHE report. Both link to a THE article. Has the independent analysis itself been published, or is the THE report all we have?

Hi Richard, it looks like you can access the research on the UWE website: http://www2.uwe.ac.uk/faculties/BBS/BUS/Research/General/Economics-papers-2018/1801.pdf.

Thanks Sam, much appreciated.

Allen’s paper doesn’t really reflect the way that differing institutional practices in relation to marks caps for reassessment and/or academic misconduct will interact with different algorithms. If you are capping a lot of modules at 40 then the difference between algorithms that use all credits and algorithms that select the best credits will be substantial.

My experience is that even in HEIs which try to be very consistent in their policies, there is a wide variety of practice in relation to misconduct in particular. There’s very wide variation across the sector in approaches to reassessment. It isn’t sensible to look at algorithms in isolation from the rest of assessment practice.

Hello Andrew, you are right, my analysis (or simulation) is in many respects, very partial. For instance the simulations do not factor in any ‘uplifts’ for borderline candidates – which again ‘inflates’ the classifications awarded. Likewise, the range of algorithms applied is very narrow, and does not include some of the more inventive ones, or the extraordinary ones (e.g. Coventry uses only the Best 100 credits at level 3!). I am currently working on another paper which uses 20 algorithms, where the purpose is to see what proportion of student would not receive a different classification awarded (what ever the algorithm)