Who decides if a university has to close over Covid?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

What size/shape of outbreak might trigger that kind of action? How long might it last?

These and more questions are important for the autumn. A number of universities in the US, for example, have set triggers for transmission and infection that would cause them to switch plans or even close campuses. Some even have dashboards so you can watch them edge closer to closure in real time. Here, of course, the situation is a little more complex.

By now, of course, every student (both new and continuing) should know about their provider’s plans for delivery in different scenarios and in the event of changes to public health advice, and should also know what measures a provider would take in the event of a further lockdown.

But now that attempts are being made to manage the pandemic in a local and granular way, the binary “on/off” of a national lockdown as described in the OfS guidance that the above quotes from is hopefully off the cards. Rather, what Boris Johnson called “whack a mole” is in play – and students and staff as citizens of a local area really ought to both understand local public health strategies, plans in the event of a large outbreak, clusters etc and know how they might be able to influence them.

The dry document underpinning the “colour” of the “whack a mole” metaphor is (at least in England) the Covid-19 “contain” framework, which supposedly sets out how national and local partners will work with the public at a local level to prevent, contain and manage outbreaks.

First of all, unitary metropolitan councils and county councils (referred to as “upper tier local authorities”) have been asked to lead on local outbreak planning, within a national framework, and with the support of NHS Test and Trace, PHE and other government departments. Each one developed a local outbreak plan back in June setting out how partners should work together to implement the plans and take a preventative approach.

It would be fair to say that the amount of detail on higher education on offer that we’ve seen in the plans, and the potential threat to public health that students’ return to campus pose, goes well beyond reasonable allowable differences based on the characteristics of the area. In theory every plan is supposed to cover healthcare and education settings – for example defining monitoring arrangements, potential scenarios and planning the required response. But in the majority where a large university or multiple universities are in the boundary, higher education isn’t even mentioned.

Theme two of the plans is supposed to cover high-risk workplaces, communities and locations where the plan should identify and describe the intended management of high-risk workplaces, communities of interest and locations (for example defining preventative measures and outbreak management strategies). The sorts of issues we’ve identified elsewhere on the site and the sheer size of higher education’s employment and social footprint would, you would think, cause HE to warrant several mentions under Theme 2 too. Apparently not.

In the event of an outbreak (“2 or more confirmed cases associated with a specific setting with evidence of a common exposure or link to another case”) local authorities now have powers to close individual premises, public outdoor places and prevent specific events without reference to a magistrate, in order to respond to a “serious and imminent threat” to public health and control transmission in the area.

They do have to listen to advice from Public Health officials before exercising those powers – and there is a stress on working in partnership – but you can see how local political pressure might build on an LA looking at an outbreak “in” a university, even if closing a campus wouldn’t make much difference to transmission outside of the context of the campus.

Maybe most universities – having discussed with local authorities – know what their plans would be and what the triggers are for a particular size or type of outbreak. Should students and staff know? Arguably.

Local authorities also have a limited power to request people to refrain from doing anything (by “serving a notice”) for the purpose of preventing, protecting against, controlling or providing a public health response to the incidence or spread of infection or contamination which presents or could present significant harm to public health. We doubt that includes “send the students in student accommodation home to their parents”.

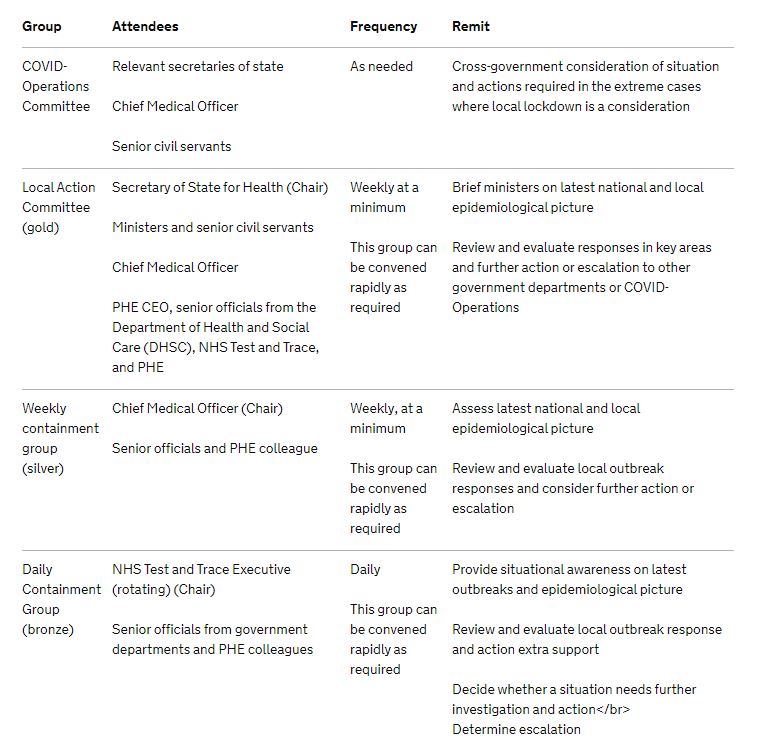

A table in the guidance sets out “key roles” for managing outbreaks within an individual setting within a local authority area. You would assume that “university” counts as an “individual setting” here – but once a university closes a campus, who manages from there? And what happens when there are multiple HE providers in a city?

And it’s in the “areas of intervention” section section where things get really interesting from an autonomy perspective. This bit looks at measures that will be most effective if there’s a major outbreak in a local authority area – and includes bespoke comms and widespread engagement focussed on as particular community, bespoke guidance to improve preventative measures, the acceleration and and expansion of channels for local testing of asymptomatic people (here it lists “students”), the closure of outdoor public areas, and the imposition of travel or movement restrictions.

The relationship between multiple higher education providers, each of which has spent the summer developing its own risk assessments and student engagement plans (and, remember, has a duty to deliver the educational services that students are paying for) with both each other, the police and a local authority under pressure over local outbreaks may well be put under major strain within a matter of weeks – and the pressure to identify common strategies where there are differences and leadership in the decision making could be very intense very quickly.